It seems like yesterday, but it was long ago. Well, not that long ago. It was 2005, and I was at dinner with a couple of car-crazy friends. One thing led to another and somehow we decided that it would be a good idea to restore a 236,000-mile 1986 Mercedes 190E 2.3-16 "Cosworth" to like-new mechanical condition, and then to campaign that car in the Tire Rack One Lap Of America time-trial event.

I cannot adequately stress just how stupid this idea turned out to be. I spent about $14,000, and another friend of mine put in something like 200 hours of labor turning a basket-case Benz into a safe-and-sound racetrack proposition. That same amount of money and effort would have gotten us a Mustang capable of running in the top fifth of the field, but applied to a four-cylinder Mercedes in which we never finished better than 55th of 97 at any of the tracks. At the end of the event, the car was a difficult sale that went for less than half of what we put into it. You get the idea, right? It was an expensive and painful lesson.

Which is not to say that the bespoilered black rennwagen didn't have its charms. It swallowed 3200 miles in seven days without a single hiccup. It was supremely stable and comfortable for high-speed, sleep-deprived transit drives across the blasted featureless moonscape of late-night Middle America. Despite its size, age, and long service history, it was a proper Mercedes-Benz in the way that some of the company's products in the years after 1986 weren't. I will go to my grave a believer in the miniaturized excellence of the W201 series in general and the 16-valve in particular.

A more specific virtue of my little 190E came as a complete surprise the first time I drove it. The transmission was a so-called "dogleg shift." Which is to say, first gear is down and to the left, with second and third in the center, and fourth and fifth to the right.

BMW used the dogleg shift pattern on its competitor for the 190E 2.3-16, the famed E30 M3, but only in European markets. Americans got a standard pattern with first and second in a line. At the time, this was generally considered to be a positive thing because in stoplight drags and U.S.-legal-speed hooning around that first-second shift is critical. With a conventional shift pattern, you just slam the lever backward and pop the clutch like Paul Walker in any one of the Fast & Furious films. Easy and quick. The dogleg, on the other hand, requires a careful up-and-over. It takes time, particularly in cars that have reverse above first gear. Wouldn't want to slam the car into "R" and let the clutch out. No, not at all.

Once you get on a racetrack, however, the brilliance of the dogleg pattern is made plain. First gear doesn't enter into the equation on a road course. Instead, it's the rapid shift to second that proves useful, particularly if you have a high-winding engine that needs the revs to exit tight corners. On the negative side, the fourth-to-third downshift is a little trickier, but that's across the middle of the pattern. Second-gear corners tend to be tight and crowded, so having the easiest shift possible for the entry (and exit) is appreciated.

It only took a few laps for me to be completely convinced of the superiority of the 2.3-16's shift layout, and although one lap has far more street-driving than track time, I was willing to sacrifice a bit of convenience in the street one-two for security in the on-track three-two. I also just appreciated having first gear well out of the mix when driving unfamiliar courses. It's one less thing to worry about.

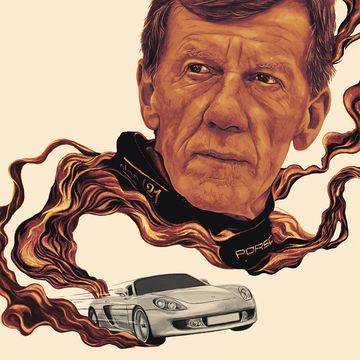

Most drivers of the Eighties didn't particularly enjoy or appreciate the dogleg pattern in the few places it appeared. The Porsche 928, which was perhaps the most commonly seen crooked-shifter in the United States, was regularly criticized in road tests for its unconventional demands on the driver. I'm not aware of a single car on the market today that has first gear down and to the left.

It's a shame, really, because in the years between the Cosworth 190 and the modern CLA45 AMG, a genuine and pervasive track-day culture has taken root in this and other countries. In 1986, the notion of taking a street car around Mid-Ohio or Laguna Seca was rather outré, but it's the most common purpose to which racetracks are put in 2013. There are numerous "country club" road courses that exist simply for the non-competitive amusement of their well-heeled members, and most of the cars you'll see out there have license plates on the back bumper. No performance car—be it a humble Fiat Abarth 500 or a mighty Porsche 991 GT3—is considered to have street cred unless it can do the business on an open-lapping day.

Today's drivers also find themselves commanding six-speed or even seven-speed manual boxes as they hustle their high-horsepower track rats from corner to corner. First gear, of course, is still useless out of pit lane, and for most cars, sixth and seventh are also mere curiosities installed for bragging rights on the autobahn or the EPA highway cycle. That leaves the traditional quadrant: two-three, four-five. Why not bring the dogleg layout back for those cars? Their owners will go faster around the tracks while throwing fewer connecting rods or valvetrains through their oil pans. Isolating the four gears that are truly of use simplifies the equation and allows the driver to focus on something.

Most important, however, it would be cool, and isn't that really why we're interested in fast cars to begin with? When I sat in my polished-up Mercedes for the first time seven and a half years ago, I looked at the wand on the center console, noted the unfamiliar pattern, and thought to myself, "They meant business, didn't they?" Yes, they did—and it's a business that justifies a grand reopening in today's fastest track-day specials.

Jack Baruth is a writer and competitor who has earned podiums in more than fifteen different classes and sanctions of automotive and cycling competition, in both amateur and professional capacities, as well as an enthusiastic hobbyist musician and audiophile who owns hundreds of musical instruments and audio systems. His work has appeared in Bicycling, Cycle World, Road & Track, WIRED, Wheels Weekly, EVO Malaysia, Esquire, and many other publications. His original design for a guitar, the Melody Burner, has been played by Billy Gibbons, Sheryl Crow, and others.