Ebola: overview, history, origins and transmission

Updated 12 January 2023

1. History of the disease

Ebola virus disease (EVD) is a severe disease caused by Ebola virus, a member of the filovirus family, which occurs in humans and other primates. The disease was identified in 1976, in almost simultaneous outbreaks in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Sudan (now South Sudan).

Between 1979 and 1994, no cases or outbreaks were detected. However, since 1994, outbreaks have been recognised with increasing frequency (see section 1.2 below).

Until 2014, outbreaks of EVD were primarily reported from remote villages close to tropical rainforests in Central and West Africa. Most confirmed cases were reported from the DRC, Gabon, the Republic of the Congo, Sudan and Uganda. In 2014, an EVD outbreak was reported for the first time in West Africa (Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone). During this outbreak, which was ongoing between 2014 and 2016, there was intense transmission in urban areas, resulting in over 28,000 reported cases. Multiple countries including Italy, Mali, Nigeria, Senegal, Spain, the UK and the US, reported imported EVD cases associated with this outbreak (see section 1.3 below).

There are 6 species of Ebola virus, 4 of which are known to cause disease in humans:

- Zaire ebolavirus (EBOV)

- Sudan ebolavirus (SUDV)

- Tai Forest ebolavirus (TAFV) (formerly known as Ebola Ivory Coast)

- Bundibugyo ebolavirus (BDBV)

Reston ebolavirus (RESTV) is known to have caused severe illness in non-human primates, but not in humans. RESTV was first detected in 1989 in Reston, Virginia (US), in a colony of monkeys imported from the Philippines, and has subsequently caused outbreaks in non-human primates in Pennsylvania and Texas (US), and Sienna (Italy). Several research workers became infected with the virus during these outbreaks, but did not become ill. Investigations traced the source of the outbreaks to an export facility in the Philippines, but how the facility was contaminated was not determined. In 2008, RESTV was isolated from sick pigs in the Philippines. Several animal facility workers developed antibodies, but none reported any symptoms.

A sixth species of Ebola virus was discovered in bats in Sierra Leone in 2018 and named Bombali ebolavirus. It is not yet known if this species is pathogenic to humans.

See information on current EVD outbreaks.

1.1 Map of countries which have reported EVD cases, up to January 2023, including year of reporting and Ebola virus species

Imported cases of EVD are not included in this figure.

1.2 Outbreaks of EVD, up to January 2023 (excluding the West Africa outbreak 2014 to 2016)

| Year | Country | Location | Ebola virus species | Cases | Deaths | Case fatality rate | Additional details |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1976 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Mongala Province | Zaire | 318 | 280 | 88% | N/A |

| 1976 | South Sudan (a) | Western Equatoria State and Central Equatoria State | Sudan | 284 | 151 | 53% | N/A |

| 1976 | United Kingdom | Wiltshire, England | Sudan | 1 | 0 | 0% | Laboratory-acquired infection |

| 1977 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Sud-Ubangi Province | Zaire | 1 | 1 | 100% | N/A |

| 1979 | South Sudan (a) | Western Equatoria State | Sudan | 34 | 22 | 65% | N/A |

| 1994 | Gabon | Ogooué-Ivindo Province | Zaire | 51 | 31 | 60% | N/A |

| 1994 | Côte d’Ivoire | Taï National Park | Tai Forest | 1 | 0 | 0% | N/A |

| 1995 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Kwilu Province | Zaire | 315 | 254 | 81% | N/A |

| 1996 | Russia | Unknown | Zaire | 1 | 1 | 100% | Laboratory-acquired infection |

| 1996i | Gabon | Ogooué-Ivindo Province | Zaire | 31 | 21 | 68% | |

| 1996ii | Gabon | Ogooué-Ivindo Province | Zaire | 60 | 45 | 75% | |

| 1996 | South Africa | Johannesburg | Zaire | 2 | 1 | 50% | A medical professional was infected in Gabon and travelled to South Africa. A nurse treating the case became infected and died. |

| 2000 to 2001 | Uganda | Northern and Western Regions | Sudan | 425 | 224 | 53% | N/A |

| 2001 to 2002 | Gabon and Republic of the Congo | La Zadié, Ivindo and Mpassa Districts, Gabon and Cuvette-Ouest Department, Republic of the Congo | Zaire | 124 | 97 | 78% | Outbreak affected Gabon and Republic of the Congo |

| 2003i | Republic of the Congo | Cuvette-Ouest Department | Zaire | 143 | 129 | 90% | N/A |

| 2003ii | Republic of the Congo | Cuvette-Ouest Department | Zaire | 35 | 29 | 83% | N/A |

| 2004 | South Sudan (a) | Western Equatoria State | Sudan | 17 | 7 | 41% | N/A |

| 2004 | Russia | Unknown | Zaire | 1 | 1 | 100% | Laboratory-acquired infection |

| 2005 | Republic of the Congo | Cuvette-Ouest Department | Zaire | 12 | 10 | 83% | N/A |

| 2007 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Kasai [Kasaï-Occidental*] | Zaire | 264 | 187 | 71% | N/A |

| 2007 | Uganda | Western Region | Bundibugyo | 131 | 42 | 32% | N/A |

| 2008 to 2009 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Kasai [Kasaï-Occidental*] | Zaire | 32 | 15 | 47% | N/A |

| 2011 | Uganda | Central Region | Sudan | 1 | 1 | 100% | N/A |

| 2012 | Uganda | Western Region | Sudan | 24 | 17 | 71% | N/A |

| 2012 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Haut-Uélé Province [Orientale*] | Bundibugyo | 62 | 34 | 55% | N/A |

| 2012 to 2013 | Uganda | Central Region | Sudan | 7 | 4 | 57% | N/A |

| 2014 (b) | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Équateur Province | Zaire | 69 | 49 | 74% | N/A |

| 2017 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Bas-Uélé Province | Zaire | 8 | 4 | 50% | N/A |

| 2018 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Équateur Province | Zaire | 54 | 33 | 61% | N/A |

| 2018 to 2020 | Democratic Republic of the Congo (c) | North Kivu, Ituri and South Kivu Provinces | Zaire | 3,470 | 2,287 | 66% | N/A |

| 2020 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Équateur Province | Zaire | 130 | 55 | 42% | N/A |

| 2021i | Democratic Republic of the Congo | North Kivu Province | Zaire | 12 | 6 | 50% | N/A |

| 2021 | Guinea | Nzérékoré Region | Zaire | 23 | 12 | 52% | N/A |

| 2021ii | Democratic Republic of the Congo | North Kivu Province | Zaire | 11 | 9 | 82% | N/A |

| 2022i | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Équateur Province | Zaire | 5 | 5 | 100% | N/A |

| 2022ii | Democratic Republic of the Congo | North Kivu Province | Zaire | 1 | 1 | 100% | N/A |

| 2022 | Uganda | Central, Eastern and Western regions | Sudan | 164 | 77 | 47% | N/A |

| Total | 6,324 | 4,142 | 65% |

(a) This outbreak occurred in an area that is now part of South Sudan (formerly part of Sudan).

(b) not linked to the 2014 to 2016 West Africa outbreak

(c) during this outbreak, 4 imported cases were confirmed in Uganda. These cases died in the DRC and are recorded in the DRC case count.

*Previous name for province/area of outbreak

Suspected, probable and confirmed EVD cases are included. Reports from the Philippines (1989 and 2008), and the US of humans with antibodies to Reston ebolavirus, but with no EVD symptoms, were not included in this table.

1.3 EVD cases that occurred during the West Africa outbreak 2014 to 2016, caused by Zaire ebolavirus

| Country | Cases | Deaths | Case fatality rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone | 28,610 | 11,308* | 40% |

| Mali | 8 | 6 | 75% |

| Nigeria | 20 | 8 | 40% |

| Senegal | 1 | 0 | 0% |

| Italy | 1 | 0 | 0% |

| Spain | 1 | 0 | 0% |

| UK | 1 | 0 | 0% |

| US | 4 | 1 | 25% |

| Total | 28,646 | 11,323* | 40% |

*Note that the number of deaths reported during this outbreak were likely to have been underestimated.

Source: World Health Organization (WHO).

2. Natural reservoir

The natural reservoir for Ebola virus is believed to be fruit bats from the Pteropodidae family. Non-human primates are known to have been a source of human infection in a number of previous EVD outbreaks, however, they are considered incidental rather than reservoir hosts as they typically develop severe, fatal illness when infected and viral circulation is not believed to persist within their populations.

3. Transmission

Ebola virus is introduced into the human population through contact with blood, organs, or other bodily fluids of an infected animal. The first human EVD case in the West Africa outbreak (2014 to 2016) was likely infected via exposure to bats. In addition to bats, EVD has also been documented in people who handled infected chimpanzees, gorillas and forest antelopes, both dead and alive, in Cote d’Ivoire, the Republic of the Congo and Gabon.

Ebola virus can be transmitted from person to person through direct contact with the blood, organs, or other bodily fluids of an infected person. People can also become infected with Ebola virus through contact with objects, such as needles or soiled clothing, that have been contaminated with infectious secretions.

Burial practices that involve direct contact with the body of an infected person may also contribute to transmission.

Ebola virus can persist in some areas of the body even after acute illness. These areas include the testes, interior of the eyes, placenta, and central nervous system. Transmission via sexual contact with a convalescent case or survivor has been documented. The virus can be present in semen for many months after recovery.

Where there are insufficient infection control measures or barrier nursing precautions implemented, healthcare workers are at risk of infection through close contact with EVD patients. Laboratory-acquired EVD infections have been reported in England (in 1976) and Russia (in 1996 and 2004).

There is no evidence of transmission of Ebola virus through intact skin or through small droplet spread, such as coughing or sneezing.

4. Symptoms

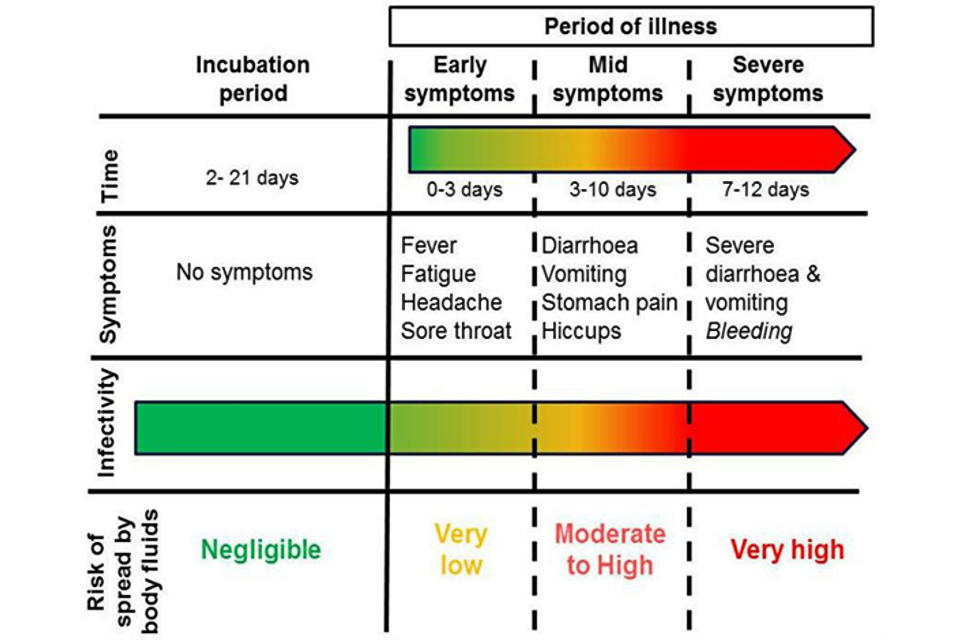

The incubation period of EVD ranges from 2 to 21 days, with an average of 8 to 10 days.

The onset of illness is usually sudden, with symptoms of fever, headache, fatigue, muscle pain and a sore throat. Gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, diarrhoea and vomiting usually follow after a few days. Some patients may develop a rash, cough, shortness of breath, red eyes, hiccups, impaired kidney and liver function and internal and external bleeding.

Between 25 to 90% of all clinically ill cases of EVD are fatal, depending on the virus species, patients’ age and other factors.

The diagram below outlines how a person’s infectiousness changes over time, following infection with Ebola virus. When a person is displaying no symptoms, or early symptoms such as fever, the level of virus in the body is very low, and is likely to pose a very low risk to others. Once an individual becomes unwell with symptoms such as diarrhoea and vomiting, then all body fluids are infectious, with blood, faeces and vomit being the most infectious. When someone reaches the point at which they are most infectious, they are unlikely to be well enough to move or interact socially. Therefore, the greatest risk at this stage of infection is to people involved in their care. Skin is likely to be contaminated in the late stage of disease, because of the difficulty of maintaining good hygiene.

5. Diagnosis

Clinical diagnosis of EVD in the early stages of infection is difficult, as early symptoms are non-specific and similar to those of other infections such as malaria, typhoid and meningitis.

Laboratory diagnosis must be carried out under high-level biological containment conditions. Diagnosis of acute infection is by reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for viral RNA. The virus can also be isolated in tissue culture, but this is only used for research purposes. Serological tests may also be available for research use.

In the UK, laboratory diagnosis is performed by the Rare and Imported Pathogens Laboratory.

See Viral haemorrhagic fever: sample testing advice.

6. Treatment

EVD patients require intensive supportive therapy, including intravenous fluids or oral rehydration with solutions including electrolytes and maintenance of oxygen status and blood pressure.

Two monoclonal antibodies, REGN-EB3 (Inmazeb™) and mAb114 (Ebanga™) are available for the treatment of EVD caused by Zaire ebolavirus. The WHO’s Therapeutics for Ebola virus disease guidance recommends the use of REGN-EB3 and mAb114 for patients with laboratory confirmed EVD infection and for neonates 7 days old or younger with unconfirmed EVD status, who are born to mothers with confirmed EVD.

There are currently no licensed therapeutics for the treatment of EVD caused by Sudan ebolavirus. Monoclonal antibody therapeutics may be used within clinical trials.

7. Prevention

To avoid person-to-person transmission of Ebola virus, great care needs to be taken when nursing patients to avoid contact with infected bodily fluids.

Patients should be isolated, and strict barrier nursing techniques should be used, including wearing masks, gloves and gowns. Invasive procedures such as the placing of intravenous lines, handling of blood, bodily secretions, catheters and suction devices are a particular risk and strict infection control is essential.

See detailed guidance for the management of EVD and other viral haemorrhagic fevers including infection prevention and control.

Non-disposable protective equipment must be properly disinfected before re-use. Other infection control measures include proper use, disinfection, and disposal of instruments and equipment used in caring for patients.

The bodies of those that have died of EVD remain highly infectious and should be promptly and safely buried or cremated.

Two vaccines are licensed for the prevention of EVD. The rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine (ERVEBO®) protects against EVD caused by Zaire ebolavirus and is used for adults over 18 years old. rVSV-ZEBOV is given as a single injection into muscle (intramuscular) around the shoulder or thigh. rVSV-ZEBOV can be used as part of the response to an EVD outbreak caused by Zaire ebolavirus as only a single dose is required to elicit an immune response. In the context of an outbreak, the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) advising the WHO, recommends that individuals who have already been vaccinated more than 6 months earlier, should be revaccinated if they are among the contacts, or contacts of contacts, of a confirmed case.

The second vaccine available to protect against EVD caused by Zaire ebolavirus is delivered as 2 doses. The first dose, Ad26.ZEBOV-GP (Zabdeno), is given followed by a second dose, MVA-BN-Filo (Mvabea), 8 weeks later. The 2 doses are administered as injections into the muscle (intramuscular) around the shoulder or thigh. Ad26.ZEBOV-GP and MVA-BN-Filo can be used in adults and children over one year old. The vaccine requires 2 doses and is therefore not suitable for use in outbreak response where immediate protection is necessary. People who have previously received Ad26.ZEBOV-GP and MVA-BN-Filo injections more than 4 months earlier and are at immediate risk of infection can receive a booster dose of Ad26.ZEBOV-GP.

There are currently no licensed vaccines for the prevention of EVD caused by Sudan ebolavirus. According to WHO, current evidence shows that ZEBOV vaccine (which is highly effective against Zaire ebolavirus), does not provide cross protection against Sudan ebolavirus. At least 6 candidate vaccines against Sudan ebolavirus are in different stages of development, including 3 vaccines with Phase 1 data (safety and immunogenicity data in humans).

8. UK guidelines

The UK has specialist guidance on the management (including infection control) of patients with EVD and other viral haemorrhagic fevers.

This guidance provides advice on how to comprehensively assess, rapidly diagnose and safely manage patients suspected of being infected within the NHS, to ensure the protection of public health.