West Virginia Senate primary features 'a convict, a carpetbagger and a turncoat'

There are two Republican candidates in the West Virginia Senate race who claim to be huge Trump supporters, but don’t really have much in common with the renegade president.

Then there is the one candidate who didn’t even talk that much about Trump during a nationally televised debate this week on Fox News, but is the most Trumpian of the bunch, by far.

And so when moderator Bret Baier asked the two more establishment-minded candidates Tuesday night about special prosecutor Robert Mueller, their eagerness to prove their loyalty to Trump inadvertently bolstered the message of the third candidate, Don Blankenship.

Patrick Morrisey and Evan Jenkins competed to outdo one another in their denunciations of Mueller. “It’s a witch hunt,” said Morrisey, the state’s attorney general. “End this investigation now!” thundered Jenkins, a congressman representing the southern third of West Virginia.

But Morrisey and Jenkins’ attacks on Mueller amplified a larger idea, that federal law enforcement officials cannot be trusted to fairly administer justice.

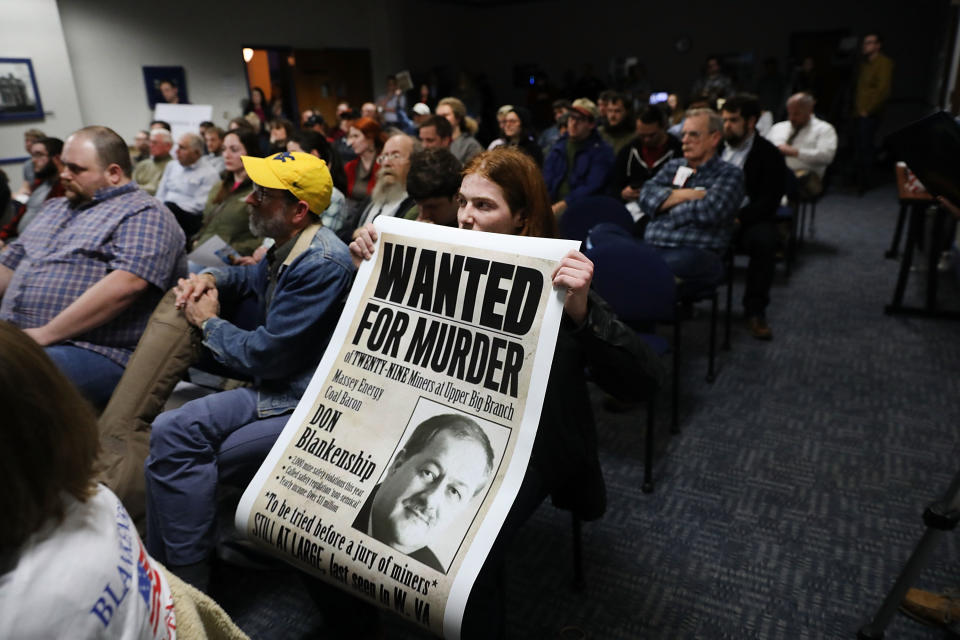

And what a gift that was to Blankenship, a wealthy coal-mine magnate in his first run for office, whose path to victory rests in part on his ability to persuade voters that his misdemeanor conviction stemming from a 2010 mine explosion was actually an Obama-administration conspiracy. Twenty-nine miners died in the incident. Blankenship, convicted of mine-safety violations, served a year in prison, and was released a year ago.

“It was a fake prosecution,” Blankenship said during the Fox debate.

During his time at Taft Correctional Institution in California, the 68-year old businessman wrote a 67-page manifesto titled “An American Political Prisoner.”

Multiple reports have found that the Upper Big Branch mine explosion was caused by a buildup of coal dust that would not have occurred had mine operators followed proper safety procedures. Blankenship, according to prosecutors, had failed to hire safety workers or pay for appropriate ventilation equipment.

But Blankenship accuses the government of going after him to cover up the real reason the explosion occurred: meddling and burdensome regulators at the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA).

“There was misconduct by prosecutors, judges, law clerks, and the FBI, as well as President Obama, Senator Joe Manchin, and the head of the Mine Safety and Health Administration,” Blankenship claimed in his pamphlet.

If Blankenship wins the primary Tuesday, his faceoff with Manchin in the general election will be a bitter grudge match. Manchin was governor of West Virginia at the time of the Upper Big Branch tragedy, and after the investigations were concluded, Manchin said in 2014 that “Don has blood on his hands.”

But Trump has distanced himself from Blankenship, and his son Donald Trump Jr. provided some insight Thursday into what his father might be thinking when he asked West Virginia voters to “make a wise decision and reject Blankenship.”

In a series of tweets, Trump Jr. compared Blankenship to Roy Moore, the Alabama Republican who lost to Democrat Doug Jones in a special election for an open U.S. Senate seat last December. Moore had faced accusations, which he denied, of inappropriate conduct with teenage girls when he was in his 30s. “The first thing Manchin will do is run ads featuring the families of those 29 miners killed due to actions that sent you to prison. Can’t win the general,” Trump Jr. said.

Ha, now I’m establishment? No, I’m realistic & I know the first thing Manchin will do is run ads featuring the families of those 29 miners killed due to actions that sent you to prison. Can’t win the general… you should know that & if others in the GOP won’t say it, I will. https://t.co/3dBmoVrMF1

— Donald Trump Jr. (@DonaldJTrumpJr) May 3, 2018

Given the dearth of polling in West Virginia, however, it’s hard to know exactly how much the state’s Republican voters are going to hold the disaster against Blankenship in next Tuesday’s primary.

“I see almost as many people saying, ‘Give him a chance, he served his time,’ as are saying, ‘It’s a conspiracy,’” said Robert Rupp, a political science professor at West Virginia Wesleyan College. “But I’m surprised by the number of people who are ready to dismiss the conviction that was proven in court.”

The undecided vote has been consistently around 20 percent. “Are they really for Blankenship and they just don’t want to get in an argument?” Rupp wondered.

Blankenship was a well-known figure long before the UBB mine disaster. He has never held elected office, but he has been one of the biggest players in state politics for nearly two decades. During the 2004 election, he spent $3 million of his own money to unseat a state Supreme Court justice. Since then, Blankenship has worked, through skilled political operatives like his righthand man Greg Thomas, to mount various political offensives, some successful and some less so.

If not for the UBB disaster, in fact, he’d most likely be running away with the primary, although his xenophobia-tinged comments about “China people” have drawn negative attention this week.

“He’s the only one not working off talking points or at least is good at coming off like he’s not,” said Gary Abernathy, a former executive director of the West Virginia GOP.

Blankenship has a shot at winning the primary because the two candidates who have been polling ahead of him recently — Jenkins and Morrisey — have huge political liabilities of their own.

Morrisey is a bulldog with an elite resume. He was a high-ranking Congressional staffer for several years, and then an influential D.C. lobbyist. This experience was an asset in politics for many years, but now it is a turnoff to voters. In addition, Morrisey’s wife is also a powerful lobbyist who has worked for large pharmaceutical companies that produce opioid pills.

West Virginia has been hard hit by the opioid crisis, in part because drug companies have flooded the state with pills. Morrisey argues that he has cracked down on opioids as attorney general in the state, but his long track record of lobbying for Big Pharma, and his wife’s, too, is troubling to many in the state.

Further, Morrisey, 50, did not move to West Virginia until 2006. He lived most of his life in New Jersey and ran unsuccessfully for Congress there in 2000.

Morrisey’s lack of local roots does not sit well in this insular state.

“We suffer from the missionary complex,” Rupp said. “For the last 150 years, outsiders come in not only to exploit [the state] but to make it better. They think they know better. There’s a tremendous resentment of that.”

Morrisey is endorsed by the most conservative candidates, like Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, and Sen. Rand Paul, R-Ky., as well as outside groups on the right. But Blankenship’s authentic and fiery Trumpism, even if it is delivered in a soft-spoken drawl, may appeal more to a population that feels looked down on.

Bo Copley, the laid-off miner who famously confronted Hillary Clinton at a campaign event during the last presidential election, is also running, although he is not polling among the leaders.

Jenkins is the likely beneficiary if Morrisey and Blankenship falter.

Jenkins’ greatest strength may be that he is the least offensive of the top three candidates. He’s a former Democrat who switched parties in 2013. He is good-looking in a local-news-anchor sort of way: tall, fit and neatly coiffed. Jenkins projects the polished, even glib, personality of a successful car salesman, not necessarily an asset in this state.

The short and stocky Morrisey has worn jackets, sweaters and hard hats in his TV ads. Blankenship — rumpled, laconic, but with a quiet intensity — comes across as the most authentic West Virginian.

“We’re West Virginians. We’re West Virginians through and through. My family has been here for generations,” Jenkins emphasized in an April debate, apparently mindful of a need to convince voters of his authenticity.

And so West Virginia Republicans will have plenty to consider as they go to the polls Tuesday.

“You have a convict, you have a carpetbagger, and you have a turncoat,” Rupp said. “We couldn’t have a designed a better primary for you to look at.”

Trump admits he reimbursed Cohen for Stormy Daniels ‘hush money’ payment

Anti-Semites on the ballot: GOP ‘condemns’ three contenders with racist views

As House wraps up Russia inquiry, top Dem on Senate probe says there’s no end in sight

After relief debacle, Puerto Rico’s governor looks for political revenge in Florida