Second of two parts

Who are the Wikipedians, these unsupervised volunteers with strange pen names such as Schzmo, Hooperbloob, and Chlewbot, most of whom will never meet face to face? Who are these people who made Wikipedia, the phenomenal online encyclopedia of almost a million articles in English, with no one leading or directing them?

There is no simple answer, since they're spread all over the English-speaking world. But leaving aside the vandals who do their worst to wreck the project, interviews with participants over the past few weeks can be pieced together into a partial profile.

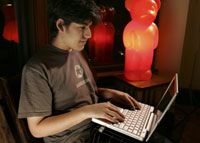

Wikipedians -- as they call themselves -- tend to be young, bright, lively readers. They are highly educated, intellectually curious, sociable, interested in many things and in finding new interests. They are computer-savvy, accustomed to the world of Google, blogs, user groups, meetups, instant messaging, and free and open information on the Internet. According to Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales, there are many more males than females.

They are also idealistic and optimistic about people and the good things they can accomplish when they collaborate. And they're confident they can outlast, outwit, and defeat the people they call trolls and vandals, who represent the dark side of Wikipedia.

To some observers, the undirected, anonymous nature of Wikipedia is disturbing: Who are the people writing these articles, and why should anyone trust what they write? But to the Wikipedians, that mass of unmanaged anonymity is what makes Wikipedia great.

''To me, it's natural and obvious that people should contribute to this kind of project," said Samuel Klein, 27, a programmer and Harvard student. ''My view of a socially efficient and well-connected world is that everyone who learns something new and interesting instantly shares it with people around them. And if they can, with various technology advances, they distribute it to as many people as possible."

Klein's name on Wikipedia is SJ. Slightly built, polite, with a low, soft voice, he began contributing to Wikipedia two years ago and was hooked. Since then, he has become the de facto leader of the Boston Wikipedia meetup group -- calling frequent meetings at local restaurants to plan the second global Wikipedia conference, to be held at Harvard in August. Klein attended last year's event, in Germany, which drew 380 participants representing 51 languages.

He interrupted his Harvard studies to work on a start-up business in language-translation software, and hopes to get his degree in physics this year. He's a Wikipedia administrator and a steward -- which gives him the power to create administrators in non-English versions. Last year, he ran unsuccessfully for a seat on the Wikimedia Foundation Board of Trustees, the highest level in the project.

Anyone can register as a user on Wikipedia -- even make changes without registering. But active users who gain a reputation for responsible contributions can run for one of several levels of volunteer management. Each level has a greater degree of power and responsibility on the Wikipedia site. The basic level is administrator, which includes the power to lock articles that are being vandalized. Above that, in order, are bureaucrats, stewards, developers, and Wikimedia Foundation trustees. Voting for the candidates is open to all registered users.

Klein does not take lightly the recent libel against retired Tennessee newspaper editor John Seigenthaler Sr., who was falsely implicated in the assassinations of John and Robert Kennedy in a Wikipedia biography last year. The false information has since been corrected.

''It's a huge deal," Klein acknowledged. Yet he's confident a new rule requiring all contributors to cite their sources will help, as will better organization and better tools to fight vandalism. ''Even if there were a huge influx of people trying to produce bad content," he said, ''there are many people with the tools, and the community's trust, to fight back."

Other Wikipedians say the Seigenthaler incident is symptomatic of a truth that transcends Wikipedia.

''It's the whole Internet," said Deborah Elizabeth Finn of Boston. ''I'm very aware of it as a blogger. I never say anything negative or personal about a person. I always think, 'Would I want my parents to read this?' " Even so, Finn said, ''Freedom of speech is such a drag. The only thing worse is no freedom of speech. It's like the problem of being alive -- you could die at any time, and the suspense is hard to take."

Finn, a consultant who helps nonprofit organizations harness the Internet, belongs to the Boston Wikipedia meetup group. She's bubbly and enthusiastic. ''Wikipedia is an ethos," she said. ''It's a perfect system of meaning, because you can help construct it."

The bulk of Wikipedians seem to be young. ''I'm 48, probably double the mean demographic of most Wikipedia writers," said David Denniston of Santa Barbara, Calif., who has written 400 articles on early music. ''There are a lot of people in their teens or early 20s, mostly focused on pop culture. There's an enormous number of articles on every rock band, TV show, and character you can think of."

For the young, relying on information found free on the Internet -- whatever their interests -- is as natural as taking a book off a library shelf was for their parents.

''When I need to find information about something, I usually go to Wikipedia first," said Harrison Chen, 16, a junior at Chelmsford High School. ''I like it as a reference -- it feels good that I am contributing to it, and that others will read something I wrote and find it useful. I added an article about one of the artists on 'The Simpsons' who came from Chelmsford. I know a lot of colleges don't like Wikipedia because you can edit it," he said. ''I do cite it, because most of my teachers don't mind."

While many in education sneer at Wikipedia, others are intrigued. ''One reason I got involved is that I'm a librarian," said Jessica Baumgart, 30, of Somerville, who works in the Harvard press office. She attends the Boston group's meetings. ''A lot of my colleagues are concerned about Wikipedia," she said, ''mainly that you don't know the credentials of people who write the articles. I thought getting involved would give me a perspective that I could share with professional colleagues."

Still, she said, ''I am undecided whether this is good or bad. There are areas we need to be cautious about. Not everyone has good intentions."

For most Wikipedians, it seems the fun of the site trumps any dark concerns. Although Bill Sherman, 39, of Cambridge, has written articles about British pop culture, he doesn't believe Wikipedia should be considered an authoritative reference. ''I think it has to be taken with a grain of salt," he said. ''It's a handy and fun thing, but nobody should be writing books based on it. It's a giant graffiti board, and should be used as such."

David Mehegan can be reached at Mehegan@globe.com.![]()