Problems with the New York Leonardo Salvator Mundi Part I: Provenance and Presentation

The Art Newspaper reports that questions of authenticity, provenance and attribution constitute the greatest risks to the art market according to 83% of wealth managers and 81% of art professionals (“Ultra-rich will spend $2.7 trillion on art by 2026 says Deloitte”).

Above, Figs. 1 & 2: ArtWatch UK members’ Journal No.31 and its lead article. For membership details please contact Helen Hulson at hahulson@gmail.com .

In our current Journal (above) we carry a report on the crisis triggered by the collapsing numbers of scholars who possess specialised expertise in particular artists and fields, and on whose authority and powers of appraisal the art market relies. Scholarly shortcomings are also evident in a widespread disinclination to conduct rigorous, visually comparative interrogations of restored and/or attributed works – perhaps out of deference to institutionally-powerful picture restorers who nowadays call themselves Technical Art Historians. Some museum curators openly farm out responsibility for attributions…to private collectors. At elevated scholarly levels the highest ascriptions are sometimes attached to what are only the best surviving versions of lost works.

TELL-TALE CROPPING

The late Sir Denis Mahon supported as original and authentic a version of Annibale Carracci’s Venus, Adonis and Cupid, of c. 1588-90 until the Prado restored its own version and declared it the authentic original. Mahon saw vindication in an instantly switched allegiance:

“When I first wrote about this composition, some fifty years ago, my observations on style and chronology were based not on the Prado painting, since this was as yet unknown, but on the excellent early copy in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna and on the preparatory drawings for the figure of Adonis in the Uffizi. When the Prado painting was first published in 1965, by Pérez Sánchez, it was gratifying to realize that, although all those of us who concerned ourselves with Emilian painting had mistakenly assumed that the Vienna picture was Annibale’s original, one’s intuitions about the importance of the work and where it fitted in the artist’s evolution were confirmed.”

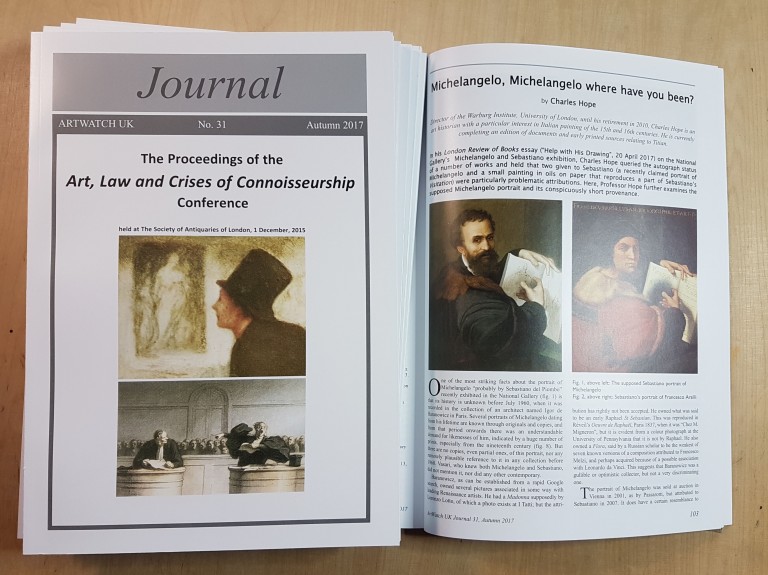

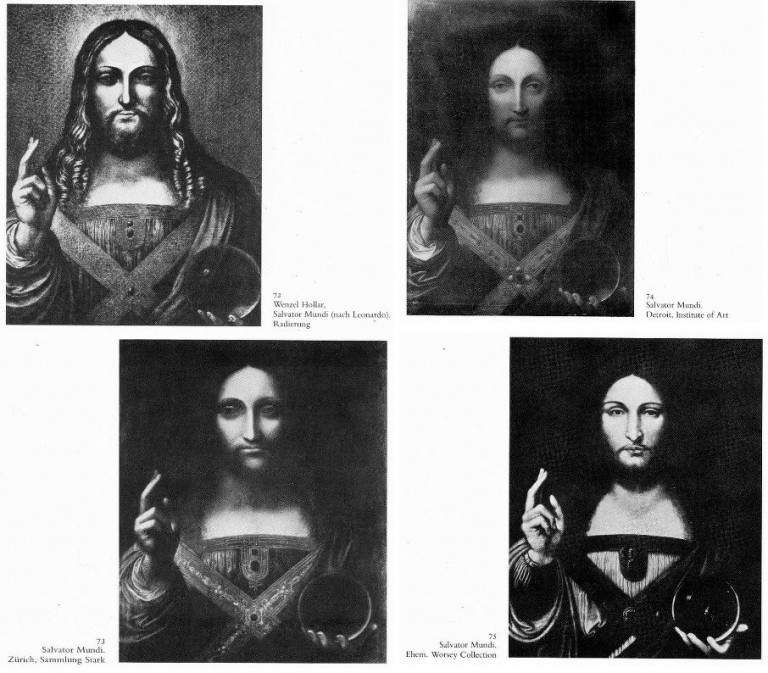

So that was alright then? No. Sir Denis was parading methodological laxity. Even before the Prado picture emerged, he should have appreciated that an old engraved copy testified that the original work was larger and compositionally richer than the cropped version he was espousing. Cropped digits and limbs are so commonly encountered in copies as to constitute attribution alarm bells. They are found (as we showed in “Art’s Toxic Assets and a Crisis of Connoisseurship”) in works given to Caravaggio, Rubens and Leonardo. Just as the thumb on Christ’s left hand in the New York Salvator Mundi is inexplicably cropped (- and nowhere addressed), so are Samson’s toes in the National Gallery’s Rubens Samson and Delilah and so are the legs and part buttocks of a slain infant in the Old Masters world record-beating Lord Thomson Rubens Massacre of the Innocents. In the National Gallery’s (second) version of Leonardo’s Madonna of the Rocks, the foot of the infant Baptist runs off the painting whereas it falls comfortably within the edge of the composition in the unquestionably autograph first version in the Louvre. It is being claimed that the New York Salvator Mundi (Fig. 3) is the prototype original for all other versions when it is in fact the only version to carry a cropped thumb (see Fig. 4). Did every other artist ignore/correct a mismanaged painted prototype composition by Leonardo?

Above, Figs. 3 and 4: Top, the New York Salvator Mundi which, since 2011 has been attributed to Leonardo (photo. courtesy of Christie’s); Above, details left, of the so-called de Ganay Salvator Mundi; centre, of the Detroit Institute Giampietrino Salvator Mundi; and, right, of the New York, Leonardo Salvator Mundi.

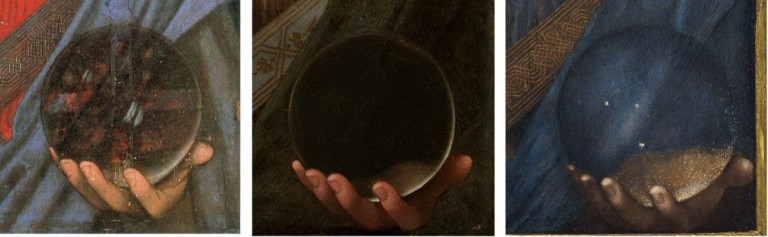

Above, Fig. 5: Left, the proposed but rejected de Ganay Leonardo Salvator Mundi; right, the New York Leonardo Salvator Mundi.

THE HISTORICAL CONTEXT OF THE NEW YORK SALVATOR MUNDI

The New York Salvator Mundi is billed as a miraculous once-in-a-century discovery when it is the second such claimant drawn from a pool of more than twenty clearly Leonardo-derived and sometimes partially Leonardo-assisted Salvator Mundis. In 1978 and 1982 Joanne Snow-Smith, with the support of the Leonardo scholar Ludwig Heydenreich, proposed that the de Ganay Salvator Mundi (above, left) was the original autograph Leonardo prototype for all other variants.

Earlier, Heydenreich had concluded on the evidence of the various treatments seen in this group – which included the then lost, now New York Salvator Mundi – that Leonardo had more likely executed designs or a cartoon to inform his assistants and associates than to have executed a finished painted panel.

THE LEONARDO SALVATOR MUNDI FIELD

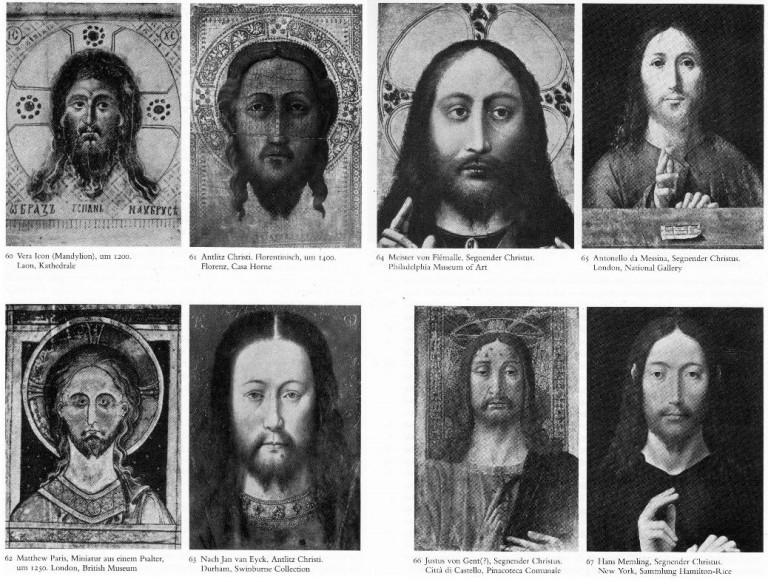

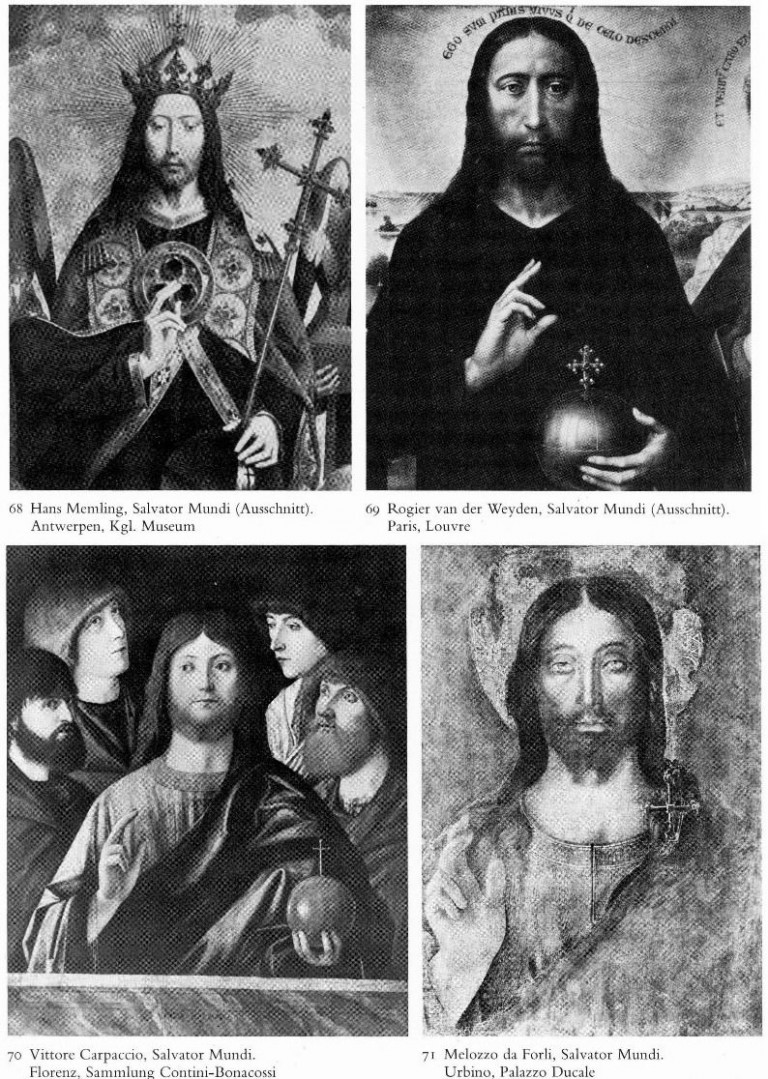

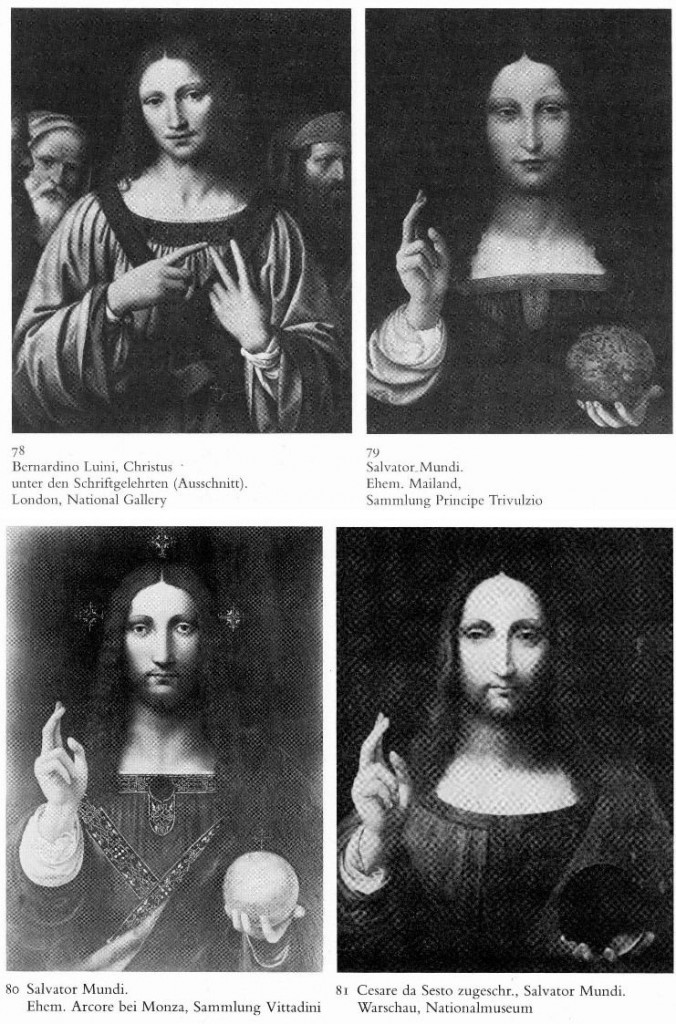

Although the quality here is very poor we reproduce below at Figs. 6–10 all of the reproduced images included in Heydenreich’s neglected but, as Frank Zöllner holds, “enduringly significant” 1964 study “Leonardo’s ‘Salvator Mundi’”. The initial images set the scene and context of the subject, others are examples of the score or more Salvator Mundi works now associated with Leonardo.

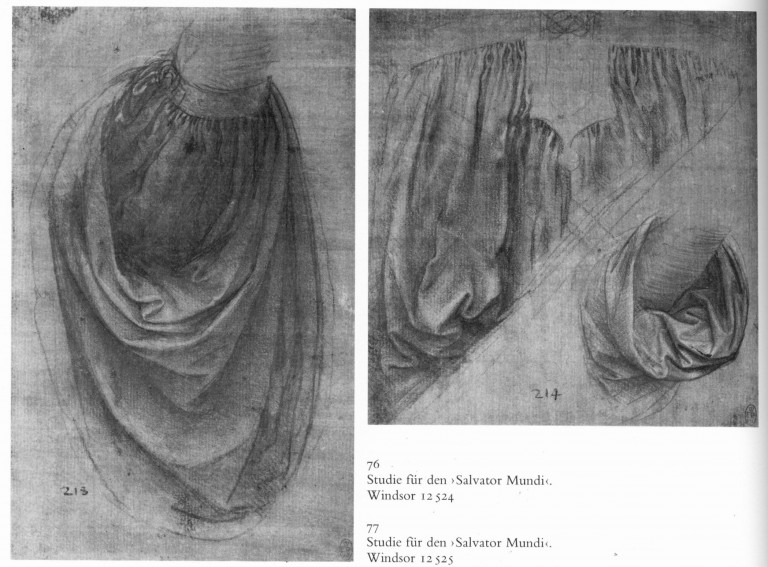

Above, Fig. 10: This image is crucial to the attribution, being the two (Windsor Castle) drapery studies that comprise the entire extant material evidence for Leonardo’s involvement in the genesis of the large associated group of Salvator Mundi works. Characteristic Leonardo drapery fold motifs in the two studies recur in varying ways in many but not in all of the associated works. These two sheets provide a small base for a claimed Leonardo attribution for a particular painting. At the heart of this present (contested) Leonardo Salvator Mundi attribution is, therefore, the question of whether Leonardo provided further designs, studies, cartoons and some painterly assistance to his students (as Heydenreich held and Frank Zöllner now holds), or whether Leonardo painted a prototype painting which provided the basis for all of the many variant Salvator Mundis. What is for sure is that there exists no study by Leonardo for an otherwise out-of-character fully frontal view of Christ’s face, or for the distinctive and recurrent hand/orb motif.

This quest for an autograph prototype Leonardo painting might seem moot or vain: not only do the two drapery studies comprise the only accepted Leonardo material that might be associated with the group, but within the Leonardo literature there is no documentary record of the artist ever having been involved in such a painting project. The first record of a work of this subject by the (attributed) hand of Leonardo occurs only in the 17th century in England.

THE OPPORTUNITY FOR LEONARDO TO PAINT A SALVATOR MUNDI

That there should be no more than a couple of drapery studies and absolutely no mention of Leonardo’s involvement on such a painting fits with records that do exist of his activities at the post-1500 period. Jacques Franck, the expert of Leonardo’s painting techniques and a restoration adviser to the Louvre, notes that:

“By 1500 onwards, the period in which the painted panel is said to have been executed, for want of time Leonardo produced few works. Fra Pietro da Novellara, who visited his studio in April 1501, reported: ‘His mathematical researches have so much distracted him that he can’t stand the brush’, and, he added, ‘Two of his pupils make copies to which he adds some touches from time to time’. In 1501, he was commissioned to produce a ‘Madonna of the Yarnwinder’ by Florimond Robertet (the French King Louis XII’s secretary) at the time when he was already creating both the major group ‘The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne’ and the phenomenally accomplished ‘Mona Lisa’. Both panels were seen during their executions in October 1503 by Agostino Vespucci, an assistant of Machiavelli at the Signoria in Florence but he, too, made no reference to a Salvator Mundi. Giorgio Vasari says of the ‘Mona Lisa’s’ execution that Leonardo, as a meticulous and slow-working painter had ‘toiled over it for four years’. Between May and August 1502 until early 1503 Leonardo was committed with Cesare Borgia as an architect and general engineer in the Marches and Romagna. He was then fully employed by the City of Florence during the Summer of 1503 as a military architect and, two or three months later, he worked fully on the commission of a huge mural (the now destroyed ‘Battle of Anghiari’) until late May 1506, before travelling between Florence and Milan up to mid 1508, because of his appointment as painter and engineer to the French King while serving Charles II d’Amboise, the new governor of Milan. Because of such taxing commitments – and all of the above were in addition to his intense scientific researches and literary activities – Leonardo increasingly resorted to workshop productions from 1500 onwards. The ‘Salvator Mundi’ must, of necessity, be thought to be one of those works and, given the preceding it is very likely that a fully original version never existed.”

THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF THE NEW YORK SALVATOR MUNDI

Christie’s lists a broad group of international scholars and experts to whom the painting had been shown at various points between 2007 and 2010, which is to say only after “the initial phase of conservation” had been completed between 2005 and 2007. It says also that there exists a “broad consensus that the Salvator Mundi was painted by Leonardo da Vinci, and that it is the single original painting from which the many copies and student versions depend” with most placing it in the later 1490s while some date it slightly later and believe it to have been painted over a number of years. The following experts are listed:

Mina Gregori, Nicholas Penny, Carmen Bambach, Andrea Beyer, Keith Christiansen, Everett Fahy, Michael Gallagher (restorer), David Allan Brown, Maria Teresa Fiorio, Martin Kemp, Pietro Marani, Luke Syson and David Ekserdjian.

However, of the thirteen, one, Carmen Bambach, can hardly be considered a supporter of an autograph Leonardo attribution. In a review in Apollo, February 2012 (“Seeking the universal painter”) she wrote:

“The attribution of the Salvator Mundi…is an important addition to the scholarship, but requires a more qualified description, for its severely damaged original painting surface exhibits a large proportion of recent integration [i. e. new, superimposed painting]. In the present reviewer’s opinion, having studied and followed the picture during its conservation treatment, and seeing it in context in the [National Gallery’s 2011-12 major Leonardo] exhibition, much of the original surface may be by Boltraffio, but with passages done by Leonardo himself, namely Christ’s proper right blessing hand, portions of the sleeve, his left hand and the crystal orb he holds.”

Of the remaining twelve, how many have written publicly in support of an unreserved Leonardo attribution? We recently asked one of those listed if he supported the Leonardo attribution unreservedly but have yet to receive a reply. One seeming casualty of the (heavy) promotion of the Salvator Mundi as the last chance to buy a Leonardo is the mixed media drawing on vellum known as “La Bella Principessa”. Is that work no longer on the market? Its Leonardo ascription was supported by two of those listed in support of the Salvator Mundi – Mina Gregori and Martin Kemp, but then, two listed supporters of the New York painting, David Ekserdjian and Pietro Marani, have roundly rejected the “La Bella Principessa” – as presumably also did Luke Syson and Nicholas Penny when the work was excluded from the National Gallery’s 2011-12 Leonardo exhibition to the annoyance of its owner and its scholarly advocates.

In addition, there is a glaring absentee on the Christie’s list – the author of the catalogue raisonné Leonardo da Vinci – the Complete Paintings and Drawings, Frank Zöllner. In the revised 2017 edition of his book, Zöllner says in his entry on the New York Salvator Mundi that while it surpasses the other known versions in terms of quality, nonetheless, it:

“also exhibits a number of weaknesses. The flesh tones of the blessing hand, for example, appear pallid and waxen as in a number of workshop paintings. Christ’s ringlets also seem to me too schematic in their execution, the larger drapery folds too undifferentiated, especially on the right-hand side. They do not begin to bear comparison with the Mona Lisa, for example. It is therefore not surprising that a number of reviewers of the London Leonardo exhibition initially adopted a sceptical stance…(Bambach 2012; Hope 2012; Robertson 2012; Zöllner 2012). In view of the arguments put forward to date and the above-mentioned weaknesses, we might sooner see the Salvator Mundi as a high-quality product of Leonardo’s workshop, painted only after 1507, on whose execution Leonardo was substantially involved. It will probably only be possible to arrive at a more informed verdict on this question after the results of the painting’s technical analyses have been published in full (Dalivalle/Kemp/Simon 2017).”

In his book’s revised 2017 preface, Zöllner writes:

“With regard to Leonardo da Vinci’s oeuvre, finally, the most sensational discovery to date has been the Salvator Mundi… The painting of Christ making the sign of the blessing has been known to art historians [only] since the start of the 20th century but subsequently disappeared from view. In 2005 it appeared on the art market and in 2011 was presented to the public in a spectacular exhibition in London (Syson/Keith 2011); since then its attribution to Leonardo da Vinci has been the subject of heated debate. This attribution is controversial primarily on two grounds. Firstly, the badly damaged painting had to undergo very extensive restoration, which makes its original quality extremely difficult to assess. Secondly, the Salvator Mundi in its present state exhibits a strongly developed sfumato technique that corresponds more closely to the manner of a talented Leonardo pupil active in the 1520s than to the style of the master himself. The way in which the painting was placed on the market also gave rise to concern.”

The long-promised delivery of the Dalivalle/Kemp/Simon technical accounts has now retreated to 2018 – seven years after the work was exhibited as a Leonardo in London and five years after it was first sold (for $80m) as a Leonardo. In 2012, Charles Hope wrote (New York Review):

“Much more suspect, however, is a recently cleaned painting of Christ as Salvator Mundi from a private collection. This was recorded in a print of the mid-seventeenth century, and the composition is known in other versions. But even making allowances for its extremely poor state of preservation, it is a curiously unimpressive composition and it is hard to believe that Leonardo himself was responsible for anything so dull.”

As shown below, the print (Fig. 11a) mentioned by Hope is crucial to the New York Salvator Mundi enjoying any provenance prior to 1900.

A HEAVILY-HYPED SALE AND THE NEW YORK SALVATOR MUNDI’S SCANT PROVENANCE

A sleeper-hunting dealer/blogger has written: “I’ve been impressed by how Christie’s have marketed the picture – in fact, I’d say that they’ve taken marketing Old Masters to a whole new level. A well deserved AHN pat on the back to all involved.” Christie’s, New York, is offering the work it describes as “The Last da Vinci” on November 15 2017 in a sale of contemporary art:

“Salvator Mundi is a painting of the most iconic figure in the world by the most important artist of all time,” says Loic Gouzer, Chairman of Post-War and Contemporary Art, “The opportunity to bring this masterpiece to the market is an honour that comes around once in a lifetime. Despite being created approximately 500 years ago, the work of Leonardo is just as influential to the art that is being created today as it was in the 15th and 16th centuries. We felt that offering this painting within the context of our Post-War and Contemporary Evening Sale is a testament to the enduring relevance of this picture.”

Few will likely be persuaded that Leonardo exerts as much influence on today’s artists as on those of his own times, and some might feel that removing the work from the context of an old masters sale will be helpful to its chances, given its heavily damaged condition and its very recently and substantially reconstructed twenty-first century appearance. There are other problems. The first concerns provenance, where the facts come late and are grafted onto a daisy-chain of hypotheses, claims and assumptions.

As mentioned, this work, now unequivocally described as a fully autograph Leonardo painting that is the artistic equal of the Mona Lisa, first materialised in 1900 when bought as by Leonardo’s follower, Bernardino Luini (- it was later taken to be a copy of a copy by Boltraffio). That purchase and what followed immediately afterwards are in the realm of verifiable facts until the painting went missing before reappearing in 2005. What is suggested to have happened before 1900 is speculation and/or contention. The first reference to such a Leonardo subject is in 1651. Christie’s provides the following provenance:

“(Possibly) Commissioned after 1500 by King Louis XII of France (1462-1515) and his wife, Anne of Brittany (1477-1514), following the conquest of Milan and Genoa, and possibly by descent to

Henrietta Maria of France (1609-1669), by whom possibly brought to England in 1625 upon her marriage to King Charles I of England (1600-1649), Greenwich;

Commonwealth Sale, as ‘A peece of Christ done by Leonardo at 30- 00- 00’, presented, 23 October 1651, as part of the Sixth Dividend to

Captain John Stone (1620-1667), leader of the Sixth Dividend of creditors, until 1660, when it was returned with other works upon the Restoration to

King Charles II of England (1630-1685), Whitehall, and probably by inheritance to his brother

King James II of England (1633-1701), Whitehall, from which probably removed by

Catherine Sedley, Countess of Dorchester (1657-1717), or her future son-in-law, John Sheffield, 1st Duke of Buckingham and Normanby (1648-1721), and probably by descent to his illegitimate son

Sir Charles Herbert Sheffield, 1st Bt. (c. 1706-1774); John Prestage, London, 24 February 1763, lot 53, as ‘L. Da. Vinci A head of our Saviour’ (£2.10).

Sir [John] Charles Robinson (1824-1913), as Bernardino Luini; by whom sold in 1900 to

Sir Francis Cook, 1st Bt. (1817-1901), Doughty House, Richmond, and by descent through

Sir Frederick [Lucas] Cook, 2nd Bt. (1844-1920), Doughty House, Richmond, and

Sir Herbert [Frederick] Cook, 3rd Bt. (1868-1939), Doughty House, Richmond, as ‘Free copy after Boltraffio’ and later ‘Milanese School’, to

Sir Francis [Ferdinand Maurice] Cook, 4th Bt. (1907-1978); his sale, Sotheby’s, London, 25 June 1958, lot 40, as ‘Boltraffio’ (£45 to Kuntz).

Private collection, United States.

Robert Simon, New York.

Private sale; Sotheby’s, New York.

Acquired from the above by the present owner

Pre-Lot Text

Property from a Private European Collection”

Thus, from a claimed execution either before or after 1500 (the supporters are divided on a possible position within Leonardo’s oeuvre) it is said to have passed through four centuries via a “(Possibly) Commissioned”; “Possibly by descent”; “by whom possibly brought to England”; “probably by inheritance”; “from which probably removed”; “and probably by descent” to 1900. It then took a further 111 years for this work to gain accreditation as a Leonardo when it was included in the National Gallery’s special exhibition “Leonardo, Painter at the Court of Milan” after a long and highly problematic restoration.

THE HOLLAR RECORD

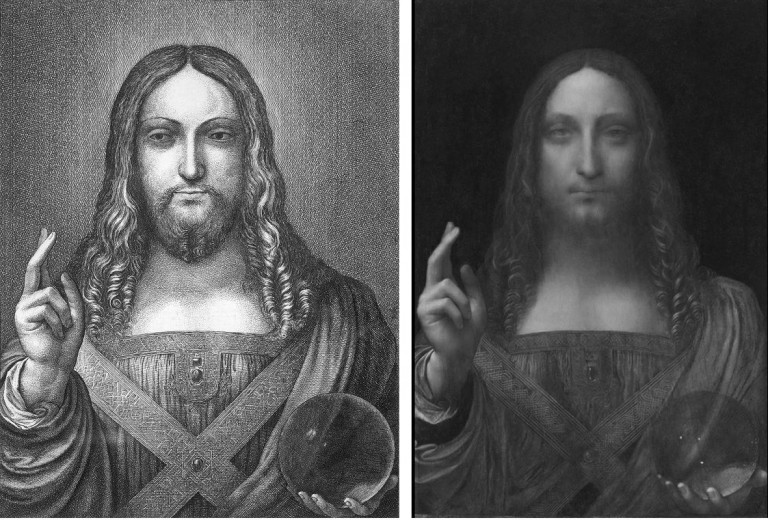

Above Fig. 11: Left, the Hollar copy declared by the engraver to be of a Leonardo; right, the New York Salvator Mundi

The 2011-12 London National Gallery Leonardo show catalogue entry on the New York Salvator Mundi was written by the (then) National Gallery curator Luke Syson, who acknowledges indebtedness to “the more detailed publication of this picture by Robert Simon [the then owner] and others…to be presented in a forthcoming book.” At first, Syson is dismissive of the seventeenth century engraved copy by Hollar which had been cited in 1978 and 1982 in support of the de Ganay version (Fig. 5a) on the grounds that the copyist, Wenceslaus Hollar, “might very well have been copying a copy.” Indeed. However, two paragraphs later Hollar commands centre stage:

“The re-emergence of this picture, cleaned and restored to reveal an autograph work by Leonardo, therefore comes as an extraordinary surprise. Though Hollar’s Christ is very slightly stouter and broader, the two images coincide almost exactly…There can be no doubt that this is the picture copied by Hollar.”

The general extent to which the Hollar copy fits the present New York Leonardo Salvator Mundi is (as seen above) is considerable, as Syson notes, but then, so too is the number of ways in which it departs from that record. Both will be examined in Part II.

Michael Daley, 14 November 2017

Leave a Reply