Operation Massacre

Rodolfo Walsh, translated by Daniella Gitlin

Seven Stories Press, $16.95 (paper)

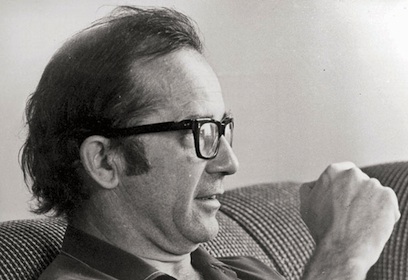

Rodolfo Walsh was a rare man of words and action, though by all accounts he struggled to reconcile the two. In a relatively short and restless life, he was a masterful chess player, a self-taught sleuth and code breaker, an award-winning fiction author turned investigative reporter, an artist and intellectual who took up a gun against his own government.

As a journalist and activist in post-revolutionary Cuba, Walsh personally intercepted and decrypted the secret CIA telex that gave Fidel Castro advance warning of the Bay of Pigs invasion. Later, in his native Argentina, he was a chief intelligence officer for the Montoneros, leftist urban guerrillas who opposed the country’s ascendant right wing.

Many Montoneros, including Walsh’s daughter Maria Victoria, became casualties of the undeclared and unofficial “Dirty War” that started some time before the military coup of 1976 and ended with the general election of 1983. On March 24, 1977, the one-year anniversary of the coup, Walsh addressed an open letter to the generals and admirals who had seized control of the state, itemizing their crimes and listing their victims: “15,000 missing, 10,000 prisoners, 4,000 dead, tens of thousands in exile.”

He devoted a large part of the letter to the newly instituted program of Kissinger-approved Chicago School economics, which Walsh considered no less ruinous than the ruling junta’s paranoid and ultraviolent mode of national security. He outlined in detail how the regime favored the foreign interests of Shell, Siemens, ITT, and U.S. Steel while prioritizing military spending to the point that Buenos Aires had devolved into “a slum with 10 million inhabitants.”

Counting off what he called “the raw statistics of the terror,” Walsh went on to make a cosmic case against the dictatorship. “You have arrived at a form of absolute, metaphysical torture, unbounded by time,” he wrote. He signed his letter “with no hope of being heard, and with the certainty of being persecuted.” Minutes after posting the first copies from a mailbox in downtown Buenos Aires, he was ambushed and machine-gunned in the street by the junta’s secret policemen.

Walsh was armed with a small pistol and apparently fired first, wounding one of the agents and ensuring that he would not be taken alive. According to Naomi Klein, who introduced many readers to Walsh with her 2007 book The Shock Doctrine, his shooters dragged him dead or dying into one of their trademark green Ford Falcons and drove him to the Navy School of Mechanics (ESMA), a notorious detention center where his body was burned and thrown in a nearby river.

Reading Klein’s book soon after it was published, I felt vaguely chastened for having known so little about Argentina, and nothing at all about Rodolfo Walsh. Five years later I came to live in Buenos Aires.

It was March 2012, and it seemed to me that Walsh was everywhere. My apartment was about ten blocks from the former ESMA facility, which was now a museum of memory and human rights, with Walsh’s open letter to the junta printed on sheets of glass outside. I got a part-time job teaching night classes at a bookshop in the city’s oldest barrio, San Telmo, and my walk to work from the nearest subway station took me around a quiet street corner decorated in Walsh’s honor. A portrait of him with a typewriter and a cup of coffee had been painted into a public mural, and a puppet-like effigy was mounted on a balcony. It looked down at me through a pair of thick spectacles.

Inscribed below in Spanish was the last line of his open letter: “Faithful to the commitment I made to bear witness in difficult times.”

Three decades removed from his historical context, I thought it would be safe to assume that Walsh was now recognized as one of the good guys. In 2011 a dozen members of the task force that took him down had finally been convicted of crimes against humanity, with two more facing further charges in the ongoing “mega-trial” of ex-ESMA personnel.

But the owner of the bookshop advised me to be careful when dropping Walsh’s name in conversation. A Maryland native with enough tenure in Argentina to know that the past remains a live issue down here, he pointed to the old framed photograph of Walsh behind the service desk, tucked away from the more prominent pictures of James Joyce, Samuel Beckett, and Virginia Woolf. Most people had no problem with it, he said, but certain elder conservatives were still inclined to think of Walsh as something like a terrorist.

The bookseller told me about one grandfatherly customer who appeared to be browsing quite happily until he noticed Walsh’s photo and practically spat on the floor, demanding to know why the image of “a killer” had been thus enshrined on the premises. I would later hear a taxi driver defend the former junta leader General Jorge Rafael Videla, who died in prison last May. Videla had been convicted for ordering forced abductions, torture, extrajudicial murders, and the theft of newborn babies from mothers imprisoned at ESMA and other concentration camps. “He wasn’t so bad,” my driver insisted.

My students tended to be younger and more left leaning. I taught one woman in her early twenties, born long after Rodolfo Walsh was killed, who confessed to being “a little bit in love with him.” Those who felt less strongly were at least aware of his work and respected him even if they hadn’t read it.

When I started a course on “new journalism,” I assigned all the big names who made an art of narrative reporting in the 1960s: Tom Wolfe, Norman Mailer, Joan Didion, Hunter S. Thompson, Truman Capote. The native Spanish speakers in the class were quick to remind me that Walsh’s Operación Masacre had been the first great “nonfiction novel,” written in 1957, almost ten years before Capote coined that term for his own true crime story In Cold Blood.

I had heard this claim made before in local literary circles, with the same defensive note of national pride that tinged the more common and less credible assertion that Argentina invented soccer, or that Buenos Aires had the world’s first public buses. But I hadn’t read Walsh’s book myself, because my Spanish still wasn’t good enough, and I’d never seen a copy in English. As it turns out, there had never been one before the brand-new translation published in September in the United States by Seven Stories Press.

Operation Massacre, to use its essentially unchanged English title, recounts a half-botched atrocity committed by Buenos Aires police under an earlier military government. On the night of June 9, 1956—in the midst of a short-lived uprising by soldiers and citizens loyal to the recently deposed president Juan Perón—a group of friends and neighbors were rounded up from a house in the working-class barrio of Florida, where they had gathered to listen to a boxing match on the radio.

Only two of those twelve or thirteen men were even remotely affiliated with the rebels, but all of them were driven to a vast open lot in the outer suburbs for summary execution. Fight-or-flight reflexes helped a few to get away; sheer luck and ballistics, coupled with the incompetence of their ad hoc firing squad, saved a few others. In total, at least six were left to tell the tale. Walsh, in turn, retold it with furious urgency. He tracked down the survivors one by one and persuaded them to talk, reporting on the fly and writing up a fistful of incendiary articles for the weekly journal Mayoría (Majority) during the austral winter of 1957.

Walsh believed ‘in the right of every citizen to share any truth that he comes to know.’

Those pieces were soon compiled into a book, Operation Massacre, by the tiny press Ediciones Sigla, at considerable risk to the publishers and to the author himself. In his introduction to that first edition Walsh wrote, “I happen to believe . . . in the right of every citizen to share any truth that he comes to know, however dangerous that truth might be.” Almost 60 years later, the book was like an unexploded ordinance, dug up from a forgotten battlefield.

As soon as I could put it down, I called the translator Daniella Gitlin in New York to ask why it had taken so long to appear in our language. “Your guess is as good as mine,” said Gitlin, who had only read the original when a friend from Buenos Aires gifted her a copy in 2009.

Gitlin told me that she tried not to polish the rough edges of Walsh’s prose. In some ways, his style made her job easier. The text, she said, did not seem “typically Spanish”—it was hard and clear where written Spanish is often “circuitous and imprecise,” in Gitlin’s words. In other ways Operation Massacre was a translator’s nightmare, with rapid shifts in tense and between first, second, and third person, sometimes within the same sentence. “It’s almost as if there is a motor behind this thing,” Gitlin said. “And you can feel Walsh changing the gears.”

Part of that effect is rooted in the looser rules of Spanish grammar, but much of it reads like technique, creating suspense and a dread sense of fate. “He will let himself be arrested without any sign of resistance,” Walsh writes of one victim, Nicolás Carranza. “He will let himself be killed like a child, without one rebellious move.” Walsh reconstructs the shooting as if he had been there himself. “The others seem stunned, resigned, bewildered. They still don’t believe, can’t believe. . . . At this moment the story ruptures, explodes into twelve or thirteen nodules of panic.” His narrative voice is profoundly partisan—empathy bleeding into solidarity.

The whole account expresses the originating sense of “insult” that Walsh felt when he first looked at the bullet-wounded face of his initial source, Juan Carlos Livraga, and heard the testimony of fellow survivor Miguel Ángel Giunta.

It kills you to listen to Giunta because you get the feeling you’re watching a movie that has been rolling in his head since the night it was filmed. . . .Once he finishes he’s going to start again from the beginning, just as the endless loop must start over again in his head: ‘This is how they executed me.’

Walsh was born in 1927 to third-generation Irish immigrants in Choele Choel, a thousand kilometers from Buenos Aires on the northern edge of Patagonia. His family was ruined by the Argentine depression of the 1930s, and he was sent to a Catholic boarding school and orphanage where he was beaten by the priests. The experience fed into his most thinly veiled autobiographical fictions and reportedly left him quick with his fists. In his angry teens he joined the far-right National Liberal Alliance but soon broke with that group and denounced it as “Nazi.”

In his twenties he became a largely apolitical artist, a promising young author of short detective stories whose debut collection won a national contest judged by Jorge Luis Borges. He was almost 30, with a wife and two daughters, when he first heard whispers of a “talking dead man” in the café where he liked to play chess. Resolving to investigate, he found that one dead man led to another and uncovered the facts of the case that he would call Operation Massacre. In the process Walsh provided critical information to the victims’ families—confirming, for example, that the still-missing Mario Brión had in fact been killed that night.

Walsh wanted his book to serve as admissible evidence against the officers responsible, up to and including Desiderio Fernández Suárez, the army-appointed police chief who had ordered the executions. But as the years passed and successive military governments refused even to acknowledge the crime, Walsh came to think of his work as a failure, at least in terms of criminal justice. “This case is no longer in process,” he writes in the prologue to the second, 1964 edition. “It is barely a piece of history; this case is dead.”

By that time Walsh had been to Cuba and back. In 1959 he co-founded the Prensa Latina news agency there with Gabriel García Márquez and Jorge Ricardo Masetti, and with the endorsement of his fellow Argentine, Ernesto “Che” Guevara. In 1960, at Havana Airport, he got the only quote that Ernest Hemingway ever gave about Castro’s revolution. “We Cubans are going to win,” Hemingway said, apparently hedging his bets on his way out of the country forever. (Papa then added, somewhat self-consciously, “I’m not a Yankee you know.”) And in April 1961, Walsh deployed his gift for puzzles and word games to decode the Bay of Pigs telex.

The trajectory of his life from that point would put him “on a par with the great revolutionaries of the twentieth century,” or so I was told by Michael McCaughan, the author of True Crime: Rodolfo Walsh and the Role of the Intellectual in Latin American Politics. I called McCaughan at home in Ireland to ask why a writer of such tremendous anecdotal appeal was barely known across the English-speaking world. The most obvious answer, McCaughan said, was that Walsh wrote in Spanish. “If he’d written in English, he would have prizes and anthologies named after him.” Sure, I said, but everybody knows his Colombian comrade García Márquez, who later described Walsh’s open letter to the junta as “one of the jewels of universal literature.”

Why hadn’t Walsh’s fiction and nonfiction been more widely translated? McCaughan guessed that it had something to do with “a sort of incomprehension surrounding Argentina.” He suggested that Walsh’s legacy had been obscured and complicated by all the twists and reversals of his country’s modern history—particularly by his association with “the highly ambiguous character of Juan Perón.”

“A lot of people still don’t know what to make of Perón,” McCaughan said. “They don’t get how this great hope of the revolutionary movement could have so much in common with fascists like Franco and Pinochet.” Which is to say that Walsh’s evolving politics may well be confusing or off-putting to foreign readers unversed in Peronism.

Even now that term seems to be the codex for explaining all the contradictions of the Argentine national character. The current president, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, calls herself and her party Peronist, but most of her opponents also identify themselves as such. In primary elections this past August, a rival candidate named Julio Bárbaro claimed to represent “El Buen Peronismo,” or “The Good Peronism,” implying that de Kirchner’s was the wrong or evil version. (Bárbaro and his running mate Julio Piumato failed to qualify for the October midterms.)

When I asked my local friends to account for this, they tended to throw up their hands. “Oh but Peronism is the purest form of politics,” said one with cheerful irony. “It is our gift to the world.” She told me to think of it not as an ideology but more an all-purpose method of governance, which relies on a single charismatic leader to tell each and every interest group exactly what they want to hear and hold the society together by sheer force of personality.

Or, failing that, by force of arms. Perón himself was the master. His rise to power in the mid-1940s was founded on an unlikely base of labor unionism, Catholic conservatism, corporatism, and military authoritarianism. If the binding of these disparate elements seemed like a kind of witchcraft, his enemies were inclined to point the finger at his wife Eva, who cast her own spell of sentimentalism across the population. The president and his first lady inspired a certain thuggishness in the cult they hadcreated, and Walsh was among thedissenters.

Almost 60 years later, the book was like an unexploded ordinance, dug up from a forgotten battlefield.

He initially supported the “liberating revolution” that ousted Perón by coup d’état in 1955, only to find the new regime no less repressive. Under General Pedro Aramburu, all mention of Perón was banned by law, and the threat posed by his loyalists provided license for the brutal policing that Walsh exposed in OperationMassacre.

As he wrote in 1958, “I don’t understand how they intend to make us choose between the Peronist barbarity and the revolutionary one.” Even after his return from Cuba, Walsh was not yet fully radicalized. But repeat visits in the late 1960s, the death of Che Guevara, and the escalating violence at home left Walsh more inclined toward the leftist hope that Perón might yet prove a true man of the people, and that militating for his return might be the best means of advancing the class struggle. Walsh never claimed to be a Peronist, but only a Marxist, “and a poor Marxist because I don’t read much.”

“My political culture is empirical rather than abstract,” he wrote. “I throw myself into life on the street.” This statement may help explain why Walsh joined the Montoneros, whose far-left interpretation of Peronism brought them into apocalyptic conflict with the far-right forces who embraced that nebulous concept with equal and opposite fervor.

For his part, Perón courted both sides from exile in Spain. He once took a meeting with Walsh himself in Madrid, but Perón gave equal time to Argentina’s land and business owners. When he landed in Buenos Aires to reclaim the presidency in 1973, his rival welcome parties shot it out at Ezeiza airport—13 people were killed and more than 300 were injured.

Before Perón died the following year, his security forces had already begun their war against the Montoneros, which soon intensified under his second wife and successor Isabel, whose own reading of her late husband’s politics tended toward the fascist. But even she wasn’t far right enough to suit the military leaders who overthrew her in 1976. Videla, Massera, Agosti, and their men then brought the fight to the Montoneros in a firestorm that left almost every member riddled with bullets or wired to electrodes in prison. It is now known that their targets also included French nuns, teenage students, and grieving mothers, most of whom were arrested and tortured at ESMA before being drugged and dropped from helicopters to their deaths in the South Atlantic or the Rio De La Plata.

October 2013 marked the 30th anniversary of the end of the Dirty War, and many of the perpetrators have only recently been tried for their part in “disappearing” up to 30,000 so-called subversives—euphemisms that no longer provide any cover for the actions of the former dictatorship. For many families and friends of those disappeared, that war is still not over. There are still unanswered questions as to the whereabouts of missing loved ones—or at least their remains—and the unsettled issue of truth and reconciliation has become a matter of electoral politics. Ahead of the midterms, President de Kirchner played up her human rights record, to set against her massively unpopular protectionist economy.

Foreign goods are blocked, domestic products are substandard and overpriced, inflation is skyrocketing, and the middle-classes of Buenos Aires are out on the streets banging pots and pans in protest. Not many object to the belated prosecution of ex-ESMA secret police, though most prefer to credit the president’s more beloved husband and predecessor Nestor, who overturned the “full-stop” and “due obedience” laws that had effectively granted amnesty to some of the junta’s worst abusers. In this new context, the ruling Peronists have recruited Walsh as a symbol of their willingness to redress long-standing injustice.

Or, as Michael McCaughan put it, “Rodolfo is now a useful and ethical figure to put on posters for a movement that has fallen short of everything he fought for.” Meanwhile, the anti-Kirchnerites and modern anti-Peronists would like to remind you that Walsh and the Montoneros bloodied their own ledger with bombings and assassinations. Walsh was invoked even before he was a member, when the Montoneros relied on Operation Massacre to justify their kidnapping and murder of the former de facto president Pedro Aramburu in 1970.

The same friend who had tutored me in Peronism also told me that Argentine schoolchildren of her post-junta generation had been taught “the theory of two demons,” which holds that the rightist and leftist violence of their country’s recent history were effectively equivalent—that the dictatorship and its enemies were as bad as each other. The more I learned about that period, the more estranged I felt from modern Buenos Aires, where I could not mention Walsh’s name without hearing inherited opinions or backdated politics. I could not find a witness to separate the dead martyr from the living writer, or tell me what the man himself was like, until I met his partner Lilia Ferreyra.

They had never married, but she was the woman he spent his last days with, and she remains his common law widow, so to speak. On a Friday night in early September—late winter in Argentina, the trees still bare and the wind still cold—I sat in Ferreyra’s small top-floor apartment, listening to her reminisce. Her memories of Walsh are a kind of indulgence, she said. She is 70 years old now and suffers from pulmonary cancer. She likes to “drift away into the past” and relies on her abiding militancy to bring her back to the present.

In 1967 Ferreyra was a chemistry student at the University of Buenos Aires and an autodidactic lover of literature. More familiar with Shakespeare than any local authors, she read a review of Walsh’s latest short story collection, and went to buy it the same afternoon. Taking the book to a nearby café, she met a friend who pointed out that Walsh himself was sitting at a table in the corner.

Ferreyra asked him to sign her purchase and soon after they went on a date. Walsh had long been separated from his wife at this point and had developed a reputation as a player, a drinker, and a gambler. But he and Ferreyra found things in common—his immigrant Irish great-uncle Willie had lived in Ferreyra’s provincial hometown of Junín—and shared roughly the same view of their country’s military rule. Walsh was changing around that time, she said.

For many families and friends of the up to 30,000 disappeared, the war is still not over.

Having famously declared, “The typewriter is a weapon,” he had come to doubt that words alone were any real substitute for bullets in effecting change, and particularly the fine words of literary artists. “Beautiful bourgeois art!” he later wrote. “When you have people giving their lives, then literature is no longer your loyal and sweet lover, but a cheap and common whore. There are times when every spectator is a coward, or a traitor.”

I asked Ferreyra if Walsh spoke like this in private too, if he was able to relax, if he had a sense of humor. “Rodolfo was a serious man,” she admitted. “He could never stop thinking.” She would watch him trim his moustache for hours, utterly distracted and absent, lost somewhere inside the mirror. But he could be a goofball too, she said. His friends called him Captain Delirio, a half-joking reference to his wild schemes and his pride as a boat owner. Walsh spent most of the mid-1960s living on an island in the Tigre Delta north of Buenos Aires, and Ferreyra said he always wished he’d been a sailor.

He taught her cryptography and turned it into a game. He made up new words and definitions for fun. He sang her songs in his tuneless baritone. When Walsh joined the Montoneros, Ferreyra did too. As the violence escalated and the danger intensified, they tried to live a normal domestic life, albeit with two guns on their nightstand—one each, next to a glass of water, every time they went to bed.

“You had to integrate the struggle into your routine,” Ferreyra said. “Otherwise you would go crazy.” After the coup of ’76, they talked about leaving the country and agreed that would be an abandonment of their cause. But even before the coup, they had broken from the Montoneros. Ever the strategic thinker, Walsh had weighed the strength of the opposition and arrived at what Ferreyra called “the probability of annihilation.”

He warned the Montonero commanders to alter their doomed course of underground resistance, to be more judicious in their use of violence, to engage at an electoral level and appeal to the hearts and minds of the majority caught in the crossfire. Walsh redirected his energies into ANCLA, a clandestine news agency he had founded to report on the junta’s activities. Many of ANCLA’s contributing activists and informers were subsequently killed or captured. Walsh lost some of his closest friends and most of his former comrades in one way or another.

His eldest daughter Vicky remained an active combatant with the Montoneros. That September she held off a squad of government commandos in a siege later known as the Battle of Carro Street, before shooting herself to avoid arrest. Soon after that, Walsh and Ferreyra withdrew from Buenos Aires to rural San Vicente.

Ferreyra described their final days together as a kind of idyll-exile in a small house with no power or running water. Walsh devoured books on farming and gardening, and they planted vegetables in the adjoining field. From his 50th birthday on January 9, 1977 until the first anniversary of the coup on March 24, Walsh worked there on his open letter to the junta.

The night he finished it, he stood outside with Ferreyra looking at the stars and told her that they hadfinally found a home. The next morning, March 25, she took a train with him into the city to mail out copies from various post boxes. They got off at Constitución station and parted in the street, per their private safety regimen, planning to meet back in San Vicente later. “Don’t forget to water the lettuce,” she reminded him, in case he got home before her. The last time she ever saw him, he was disguised as an old man in a straw hat and beige overalls.

When Ferreyra returned to their house, she found it demolished by army tanks and knew at once that Walsh had been ambushed. His death would not be confirmed until much later, and his body was never recovered. His unfinished manuscripts were also missing from the ruins of the San Vicente house, presumably looted before it was destroyed. Her own situation now hazardous, Ferreyra soon escaped to Mexico, where she lived until the end of the dictatorship. But she didn’t really want to talk about that.

Leaving Ferreyra’s apartment in San Telmo to take the subway home, I remembered that the E-line station at Entre Ríos had recently been renamed “Rodolfo Walsh,” in respect of the fact that he was shot less than one block away. I had also heard there was a memorial on the corner where he made his stand. It was nowhere near my own apartment, but I took a detour, and found the station in question still called Entre Ríos, with no visible mention of Walsh.

I asked a transit cop, and he shrugged at me. “That was for show,” he said. “Publicity for some politician. People don’t just suddenly start calling a place by some other name.” I couldn’t find the memorial either. I walked up and down the intersection of San Juán and Entre Ríos avenues until I looked down to see a tiny stone marker, placed at ankle height beside a lone, thin tree. The inscription was dated 2004 and said only that the writer Rodolfo Walsh had been disappeared from this spot by the military dictatorship.

There was a heavily pregnant woman standing outside the café on the corner. I pointed to the marker and asked her who Rodolfo Walsh was. “Sorry, I don’t know,” she said. “I’m not from this neighborhood.” It’s unfair to expect one woman to speak for a whole city’s historical memory, I thought. It’s also easy to overstate the importance of one dead man.

I went into the café and asked the clerk behind the counter what he knew about the monument. He squinted as if the name rang a bell, and referred the question to an older guy who turned out to be the manager. “Rodolfo Walsh?” he said. “He was a writer or something. They took him just outside. Or killed him, maybe. I’m not sure. I wasn’t here then. It was during the dictatorship, you know.” He smiled at me, and gave a little wink. “Don’t worry about it man, it was a long time ago.”