Joi's diving blog

My name is Joi Ito and I'm a PADI IDC Staff Instructor, EFR Instructor and DAN Instructor Trainer. This is my diving blog. My main blog is Joi Ito's Web which has an English section and a Japanese section. My other main deposit of stuff is my Flickr stream.

Search

Additional pages

- Instructor Ratings

- Certifications

- Open Water Scuba Dive Log

- Favorite Dive Shops and Charters

- Diving Buddies

- Marine life photography - Wikimedia

Site authors

Find me on...

Rebreather

The week before last, I spent a day in the pool and three days at sea completing my rebreather training with Grant. We were diving off of Jeff Jonas’s boat. (Thanks Jeff!) We were training off of Catalina where I was doing my Divemaster training in December 2010 when I took my first phone call with Nicholas Negroponte about the idea of becoming the director of the Media Lab. Seems like so long ago!

Now living in Boston, I’m doing most of my diving off of Cape Ann, Gloucester with Matt and Marissa. Marissa works with me at the Media Lab and both Matt and Marissa are rebreather divers so it’s always my bottom time that ends the dives.

I’ve been really interested in rebreathers ever since I learned about them. Probably the most exciting thing is that they are so gas efficient that your dives times aren’t limited by the amount of gas you can carry. Also, since all of the air stays “in the loop” you don’t blow any bubbles and it turns out that most undersea wildlife barely notice you’re there if you don’t blow bubbles. Lastly, since you dynamically change the gas ratios, you can optimize the decompression times substantially.

Rebreathers until recently were mostly used in the military. They are useful in the military because the lack of bubbles adds to stealth and the super-long bottom times increases range and reduces the difficulty of dealing with carrying loads of gasses around. However, this magic is achieved through sophisticated technology that adds to the complexity which increases the risks.

As computers, sensors and the other elements of rebreathers have advanced, so have the design of rebreathers and the adoption of rebreathers by recreational divers. Rebreathers are still a high risk form of diving with a variety of new ways to die, which makes the training so important.

Rebreathers are very similar to space suits or space ships. They use some sort of CO2 “scrubber” to remove CO2 from the air and adds O2 to the air as you metabolize it. The rebreather has a “loop” where one “counterlung” takes your exhaled breath and sends it through a canister that has the CO2 scrubber. The material in the scrubber reacts with the CO2 and absorbs it. There are electronics that measure the partial pressure of O2 in the air and if it is lower than the partial pressure of O2 that you have set as your “setpoint” it will fire a solenoid that injects a tiny burst of O2. The air that has been “scrubbed” and mixed with any new O2 gets pushed to the counterlung on the other side which the diver then inhales.

Although most closed-circuit rebreathers are roughly similar, there are a variety of designs. I bought and trained on a Prism 2 rebreather by Hollis. My rebreather, like many other rebreathers, has three oxygen sensors in the main “head”. Although the sensors are quite good, humidity, lower temperatures and aging can cause the sensors to fail so the three sensors serve as redundancy and a kind of “voting” mechanism to figure out the amount of O2 in your breathing loop.

This is very important because two general ways you can die involves O2 - hypoxia, not enough O2, and hyperoxia, a less commonly known way of dying. There are two types of hyperoxia that we worry about. One is damage that comes from exposure to high levels of O2 over a long period of time, which we track, but the more dangerous one is the CNS oxygen toxicity that happens when the partial pressure of O2 exceeds 1.4 or 1.6 partial pressure of O2. An O2 CNS hit causes convulsions and other symptoms, which when experienced underwater, usually causes death.

Therefore, one of the most important things that the rebreather does is track the amount of O2 and regulate the amount of O2 in your loop so that the partial pressure is always within a breathable range. A lot of the training involves what to do in case of various types of failures in this system.

The other important function is the CO2 scrubbing. Hypercapnia is what happens when there is too much CO2 in your breathing loop. Hypercapnia is what you feel when you’re out of breath and is actually the main trigger of feeling out of breath - your body is trying to eliminate CO2 in the blood stream and it is a common feeling that we all know.

The problem is that if your CO2 scrubbing system fails, it will initially feel like you’re just out of breath. CO2 sensors are still not as reliable or suitable for a diving system as O2 so most units, including mine, do not have CO2 sensors. There are various ways to try to diagnose a failure in the CO2 system, but the key is to pack the scrubbing canister well and not dive beyond the limits of the material - it is the main “perishable” material that the rebreather uses other than the gasses.

When the rebreather is working properly, you can almost forget about it, but the key is to learn how to notice and diagnose problems and have all of the recovery techniques perfected. Also, the maintenance, preparation and the checklists - much like an airplane - are super-important to make sure it is always working properly.

Another major difference from traditional scuba is that the air you exhale just goes back into the loop. This means that breathing doesn’t affect your buoyancy - which for anyone who has done traditional open-circuit diving is very strange. In open-circuit scuba, you use your breathing as the primary way to fine-tune your buoyancy and it becomes second nature allowing you to dive or ascend naturally like a fish.

In a rebreather, you have to manually change the air in your loop through adding air or venting in addition to the air in your drysuit or your BCD to change your buoyancy. Physics dictates that as you go deeper, the air pockets compress and your buoyancy becomes negative. So on a rebreather, the main way that you waste gas is when you change depth a lot requiring addition and venting of gasses - often you use your gasses less for breathing and more for adjusting buoyancy.

So why go to all of this trouble and risk? It’s really amazing. Suddenly the sound of scuba diving isn’t the sound of your bubbles - it’s quiet. You can approach fish and other wildlife and they don’t run away and swirl around you as if you weren’t there. And you can dive forever. The duration of your dives are limited, if you’re in a drysuit, by your bladder and a need to pee, and in the case of a wetsuit, usually thermal - getting too cold.

It’s an amazing piece of technology and changes everything. It’s going to take me a lot more diving on it before I feel comfortable, but I’m excited to log some more hours learning and then really using it for underwater photography, foraging and other things that suddenly become a whole new experience.

Our Ice Diving video directed by Grant. Shot at Lake Macgregor and Glacier National Park in Montana.

Feeding Caribbean Reef Sharks in the Bahamas. Videos directed by Grant. GoPro ftw.

On cover of Dive Training Magazine!

Photo by Grant W. Graves

Photo by Steve Lantz

Was on the cover of Dive Training Magazine. The photos were from our Montana ice diving trip in February.

Here’s us!

Here’s the four of us who started this thing saying Hi!

Congratulations on your Open Water, Nitrox and National Geographic certifications guys!

Diving in the Bahamas - Finished my IDC and learned how to feed sharks

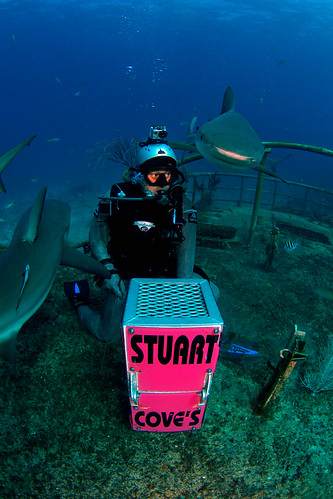

Sharks following me down to the feeding area - Photo by Sebastien Filion / Stuart Cove’s

Feeling a bit guilty as Japan still struggles with the aftermath of the earthquake, I decided to spend a few days in the Bahamas finishing up my PADI Instructor Development Course (IDC) with Grant before what appears to be a wave of work approaching me hit.

We spent the first few days in the classroom at Stuart Cove’s doing the classroom stuff and later did the teaching skills demonstrations in the pool and off to the boat. I completed all of the requirements, so pending paperwork, I am now PADI Assistant Instructor. (I liked “Divemaster” better, but in PADIland, an AI is one step up from Divemaster.) If I pass my Instructor Exam at the end of this month, I will be an Open Water Scuba Instructor. (Knock on wood…)

After we finished the IDC, we had a bit of time left so I took the shark feeder and shark aware class at Stuart Cove’s with Chang.

Shark feeding is a somewhat controversial subject. The argument against shark feeding is that they are wild animals, that it might condition them to associate human beings with food and that it could make sharks dependent on human beings and feeding for food. Feeding wild animals is generally forbidden and shark feeding is banned in many places including Florida.

People who argue for shark feeding will explain that while sharks near feeding areas will become somewhat accustomed to feeding. However, tagging and tracking has shown that a shark’s range and feeding behavior when the feeders are not around does not appear to be affected. Sharks from the Bahamas feeding areas have shown up as far away as South Africa.

The amount of food that is being given to the sharks is quite small and not nearly enough for them to become dependent or able to sustain themselves.

Me feeding Carribean reef sharks on a wreck - Photo by Sebastien Filion / Stuart Cove’s

I am generally against feeding wild animals and domestic animals that are not yours, but after looking at the facts around sharks, my personal opinion is that the conditioning and negative impact is minimal and the positive impact on dispelling fears and allowing us to capture images of and learn more about sharks has tremendous value.

Shark are opportunistic predators feeding on injured or weak fish and in the case of some species, turtles or seals. Some sharks like the great whites attack these animals on the surface and unfortunately, swimmers and surfers can look and sound a lot like seals or turtles.

Having said that, shark attacks are very rare. I’ve read that the number of crocodile victims in one year exceeds all recorded shark attacks. I’ve also read that more people are killed by wild pigs each year than by sharks.

Having gone diving with sharks and experienced exactly how picky they are and focused they are on eating only food that they can easily eat (high return / energy expended), I’m sure that a shark would never eat a human being or a human limb on purpose.

The only way to predictably see sharks up close is to draw them in with shark food, which feeders call “chum". The sharks really aren’t interested in human beings who aren’t feeding them.

There are many different styles of shark feeding, but most of them involve gathering local fish or leftovers of processed local fish to feed to the sharks. If you’re trying to attract sharks in open water or a location that doesn’t have many sharks, you may need to “chum for awhile allowing the smell to draw the sharks in. Most sharks have a very good sense of smell and can follow the scent from far away. As the sharks approach, most sharks switch to visual, vibration and sound queues to locate their food.

Unfortunately bare feet kicking underwater or on the surface sounds like injured fish and is one cause of shark attacks - sharks mistaking bare feet for hurt and struggling fish. Luckily for divers, divers don’t look like or sound like food.

After the sharks get close to the feeder, they begin to circle the diver/feeder. The key to feeding sharks safely is to feed the in a controlled way. There are roughly three “modes” of shark feeding - controlled, fast and frenzy.

Controlling the box while sharks circle - Photo by Sebastien Filion / Stuart Cove’s

If you dump a huge amount of food in the water at once, the sharks will go into a frenzy biting at everything, trying to get as much food as possible before it disappears. This is a dangerous situation where it’s possible to get bitten by mistake. You don’t ever want to be in a shark feeding frenzy.

If you feed the sharks too fast, they begin to get aggressive or “fast”, snapping and being fairly unpredictable. This is also risky.

A good feeder feeds one shark at a time every minute or two, waiting for the sharks to calm down between feeds. The feeder doesn’t control the sharks, but can exercise a great deal of influence on their mood and behavior.

My shark instructor Chang and me after our shark feed - Photo by Sebastien Filion / Stuart Cove’s

The method that I learned from my feeder instructor, Chang, was to use a spike to skewer a fish and hold it down until I could identify an appropriate shark to feed. The key was to identify a shark coming from the left side, put the fish in front of the shark so that the shark could smell it, and then pull the fish up and to the right to allow the shark to sense the motion and grab the fish. It was important to make sure the area was clear of other sharks that might try to grab the fish too or mistake my hand for the fish and bite that instead.

As the shark approaches its prey, it opens its mouth, covers its eyes with the nictitating membrane to protect them from chomp debris and uses ampulla of Lorenzini (sensors that detect electricity) to home in on the prey. Many sharks have poor eyesight and the motion is a very important way for sharks to detect prey.

A few times, sharks mistook my hand for the fish and one time I got a pretty good bite. However, the shark quickly figured out that it wasn’t food and let go. One shark got her teeth stuck in my chainmail and it was a bit awkward for both of us for a moment. Sharks, like dogs and babies, will bite things to try to figure out what they are. The bite on my hand and some of the nibbles on my leg reminded me a lot of puppies biting toys and hands.

Luckily I had a Neptunic chainmail shark suit on or the bite may have broken the skin, but with the chainmail, the bite didn’t hurt at all and I was able to be surprisingly calm. Chang had taught me a few “moves" to deal with these situations as well.

After each feeding, the sharks that didn’t get any food tended to bump into me or come looking for the food and become slightly aggressive, but even though some of them were 7 feet long and probably over 400 pounds, I was able to push them away or rub their notes and guide them away from my legs or the box of food.

Rubbing the nose of a shark puts them in a catatonic state that looks like a form of paralysis. They don’t know exactly what causes this, but some say it’s a sensory overload on the huge number of electrical sensors they have on their nose. In any case, it was relatively easy to handle the eight or so sharks that were circling me and feed them in a controlled way.

Experienced shark feeders will hold a shark still in a catatonic state to remove hooks in sharks fins and mouths. Someday, I hope I’ll be able to do this. A surprising number of sharks had hooks and I felt like spending all day removing them.

Overall, shark feeding was one of the most interesting and rewarding experiences I’ve ever had and I highly recommend it. Even though I was quite sympathetic to sharks after all of the movies and books about them, diving with and playing with sharks substantially increase my compassion and connections to sharks.

Grant and Joi - photo by Cathy Ridsdale / Stuart’s Cove

Thanks Grant, Chang and everyone at Stuart Cove’s for the great experience.

Also, thanks Grant and yay me on the IDC.

Montana ice diving

Photo by Steve Lantz

When I was reading various dive sites and dive books early in my dive training experience, one of the things that surprised me and excited me was the abundance aquatic life in the Antarctic during the warm season there. I mentioned to Grant at some point that I wanted to dive in Antarctica some day.

That promoted Grant to help organize an ice diving trip to Montana which we did a few weeks ago.

Ice diving is relatively advanced diving because it is an overhead environment, requires a lot of specialized gear, is physically somewhat challenging and requires a lot of preparation. It’s hard work and really fun and exciting, but not nearly as cold and crazy as it might seem to some people.

Grant organized the trip with his friend Steve who is a PADI Course Director and lives in Montana where ice diving in lakes is one of their main diving experiences.

We all met at the Lodge at McGregor Lake (map). When we arrived, they were getting ready for a bingo night which was the most excited I had ever seen a group of people get about bingo. The lodge itself was modest with no phones in the rooms and no cellphone coverage, but very tidy and functional. The food was all-American but was tasty and made with care.

As the group of divers trickled in over the evening and the next morning, it was fun hearing their stories and realizing that you had to be a bit hardcore to be a diver in Montana. What surprised me was how all of the divers and everyone at the lodge were super-nice and friendly. Everyone was really down-to-earth in a “real middle America” sort of way.

Montana blessed us with nice weather and although the first day was a bit drizzly, it was balmy compared to the weather a week before we arrived. The ice was 8 inches think which is just enough. The visibility in the water was excellent (this is why we chose this lake). Most importantly, Steve was COMPLETELY prepared.

We unloaded tons of specialized gear for ice diving. We had titanium ice screws, special tender line reels, a gas burner and boiling pot for heating water to warm gear and cold body parts, a huge gas heater to turn the trailer into a warm changing room, harnesses, a special chainsaw for cutting ice, rugs to make a comfy sitting bench out of cut ice, etc.

Following ice diving protocol, we first cut a hole to measure the thickness of the ice and the depth of the water. We move over to a slightly deeper area and marked our location. The divers doing the work were in drysuits and tethered so that if they fell in, they could be recovered.

We used a measuring tape to mark a triangle 10 ft on each side which would be our hole. We cleared the snow 20 ft from the hole. We then cleared circles in the snow at 50 ft and 100 ft. We cleared “spokes” from the center outward as well. The circles and the spokes allow the light to come through so that underneath the ice, they turn into a kind of “bullseye” for the diver to show where the hole is.

Photo by Grant Graves

We cut a pattern in ice where the hole would be and put ice screws into each block section small enough so that they could be lifted out with rope and carbingers. With a chainsaw, we cut the blocks and pulled them out. We stacked a few of the big blocks to make a bench that we covered with rugs.

Once everything was set up and everyone was briefed, we began diving. Each dive team consisted of two divers tethered to a single line with a “tender” up top who let out the line and used line signals to make sure the divers were OK. There were always a pair of completely geared and tethered safety divers on standby up top so that if anything happened, they could enter the water immediately and provide support.

We took turns tending, being safety divers and diving.

Photo by Grant Graves

It was an amazing experience. After the initial “did I just eat a gallon of ice cream” brain freeze and after your face got numb, it really wasn’t that cold. It helped that I was in a drysuit with nice undergarments and an electrical active heating vest on.

The water was clear and the ice was beautiful. I didn’t see much life in the lake other than some crawfish, but I really enjoyed the glacial feel of diving in the ice. After a few dives, I started to feel comfortable on and in the ice and imagined doing this in the arctic.

While the diving itself was really awesome, I really enjoyed working with the team of experienced and committed divers and found the preparation and the packing up also really fun.

Photo by Grant Graves

I’m not sure when I’ll get a chance to visit Lake McGregor again, but I sure would like to go back again sometime.

Dick Rutkowski

A few weeks ago, I visited the Knight Foundation in Miami and had a few extra days so Grant and I went to the Keys to do a bit of diving and to visit Dick Rutkowski.

Dick is a pioneer and a famous character in hyperbaric and dive medicine and pioneered a lot of the work in advanced gas mixes for diving. Dick worked at the National Oceanic and Atomospheric Administration (NOAA) since it was founded in 1970.

He is well know for being the first to suggest using Nitrox, which had been used extensively in the military, for recreational divers. Initially there was quite a bit of resistance, some even calling it a “voodoo gas”. Nitrox is a gas blend with a higher concentration of oxygen, which decreases the partial pressure of Nitrogen and increasing, among other things, the total “non-decompression dive time” available to divers and decreases decompression times for divers who go over the non-decompression limit.

I’m a huge fan and usually dive Nitrox whenever it is available. Japan is still rather behind in the adoption of Nitrox - I’ll write about this more some other time.

We visited Dick at his place in Key Largo and got to see all of the amazing historical diving and hyperbaric artifacts in addition to his working hyperbaric chambers where he still teaches hyperbaric medicine.

Since I am a certified PADI Nitrox diver, he cross-certified me with International Association of Nitrox and Technical Divers (IANTD). It was quite an honor being certified by instructor number 1 and the father of recreational Nitrox. ;-)

Dick sat in front of the whiteboard and talked gas physiology drawing diagrams and formulae reminding me of his famous quote “Science Always Wins Over Bullshit” which was written prominently on his wall.