Editor’s Note: Doug Young teaches financial journalism at Fudan University in Shanghai and is the author of The Party Line: How the Media Dictates Public Opinion in Modern China published by John Wiley & Sons. The opinions expressed here are solely his.

Story highlights

Hong Kong's pro-democracy protests have been front-page news except in China

Coverage has been limited, with focus on editorials that lack broader context

Few images of the protests have been shown on Chinese media

Authorities fear pictures could inspire others in China to take similar actions

Hong Kong’s pro-democracy demonstrations have been front-page fodder this past week in international media, which have painted the story as a David-and-Goliath struggle between local Hong Kongers and a powerful but distant authoritarian master in Beijing.

But no such headlines have appeared in China, where the story has been buried deep inside most newspapers and TV broadcasts, and is framed in a way that makes it uninteresting and unintelligible to average Chinese.

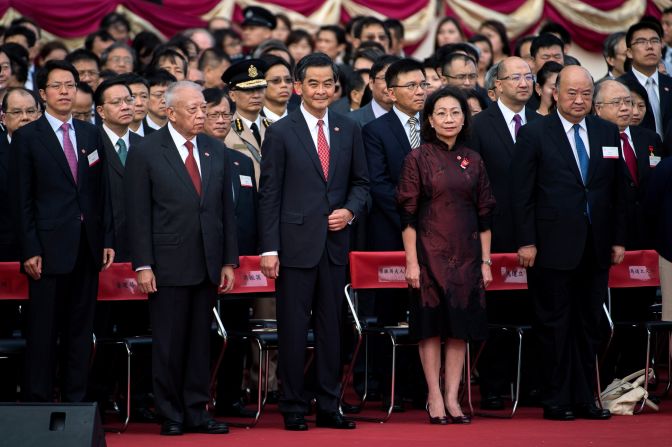

The coverage consists mostly of Beijing’s reactions to events with little or no explanation of what actually happened to prompt such response. The result is a hodgepodge of reports condemning the protests, saying that Hong Kong leader C.Y. Leung will never resign, and editorials declaring such protests will never spread to China.

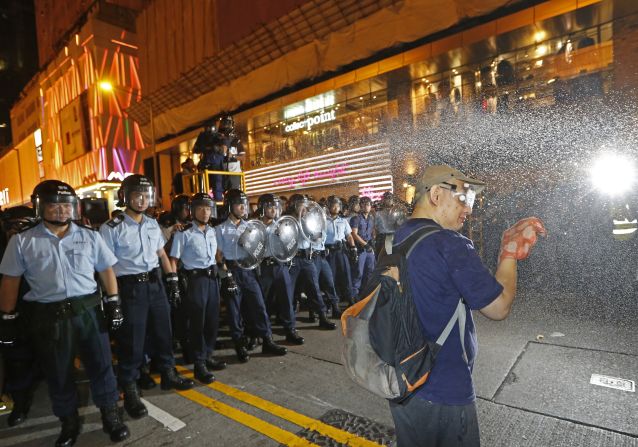

It has also been noteworthy for the relative lack of images. From a media perspective, the demonstrations now taking place are a journalist’s dream come true, featuring colorful and action-filled images of protesters, police, politicians and conflict that make for great TV viewing and photos .

Yet none of those images have found their way into China’s official media, almost certainly on direct orders from propaganda officials who worry such pictures could inspire others in China to take similar action.

Strict bans on such inflammatory images are quite common in order-obsessed China, even when such protests are pro-Chinese. One such ban was a central feature in domestic coverage of a major territorial dispute with Japan two years ago, with major protests that broke out around China eerily absent from all domestic reports.

READ: C.Y. Leung: Hong Kong’s unloved leader

Old trick

China’s media have also resorted to another old trick of covering the conflict using editorials, which offer a backdoor route into the story with little or no broader context.

In this case the official Communist Party newspaper People’s Daily has taken the lead with a series of forceful editorials repeating that such protests are illegal and adding that such actions will never spread to China.

Such editorializing has been a popular tool for stating official views on sensitive subjects since 1949, and was widely used in 2010 when Google got into a high-profile dispute over Beijing’s stipulations that it self-censor its China-based search site.

That conflict ultimately saw Google withdrawal from the China search market, only to be cast by Chinese media as a cry baby that couldn’t compete with local rivals.

Beijing has also dusted off its tried-and-true tactic of using key “buzzwords” to control the tone of the story. Two such buzzwords this time have been “illegal,” to describe the nature of the Hong Kong demonstrations, and “in accordance with the law,” to describe how the China-friendly Leung administration is handling the situation.

Finally there’s the social media element, which is a new game not only for China but governments throughout the world as they try to harness this powerful force to influence public opinion.

READ: How might China respond?

Social media

In this case, a number of commentaries have been making the rounds on popular social media platforms like WeChat, playing on themes that criticize the protesters for everything from threatening Hong Kong’s prosperity to harboring broader hostility toward all mainland Chinese.

READ: China’s ‘Great Firewall’ censors protests

These stories by little-known writers could be genuine, but are most likely a variation on another Beijing tactic to control online public opinion in the Internet age.

Known by the disparaging moniker of the “Fifty-Cent Party,” this loosely defined group’s “members” reportedly receive government payment for posing as independent commentators who seed the Internet with opinions favorable to the central government’s policies and views.

The latest protests in Hong Kong may be providing new challenges for Beijing’s leadership from a new generation of democracy-seeking activists on China’s periphery.

But the tactics being used by China’s media are anything but new, with Beijing resorting to a wide range of time-tested reporting tricks in its bid to shape the issue in the realm of domestic public opinion.