calsfoundation@cals.org

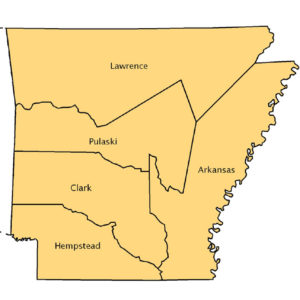

Arkansas State Boundaries

Arkansas’s boundaries have been the subject of international treaties, treaties with Native American tribes, acts of Congress, and a multitude of decisions of the U.S. Supreme Court. Generally, Arkansas is bordered on the north by Missouri; on the east by Tennessee and Mississippi; on the south by Louisiana; and on the west by Texas and Oklahoma, but that is not entirely correct. Arkansas is also bordered on the east by Missouri and the south by Texas, but parts of the state are also north of Missouri, east of Mississippi, north of Oklahoma and west of Texas.

Tennessee-Mississippi Boundary

As early as the Treaty of Paris of 1763 ending the French and Indian War, the middle of the Mississippi River was established as a boundary between European colonial powers. Arkansas’s first boundary was established after U.S. independence from England when the October 27, 1795, Treaty of Friendship Limits and Navigation between the United States and Spain established the boundary separating Spanish Louisiana, including what would become Arkansas, and the United States as the “middle of the channel or bed of the Mississippi River.” Later, when Congress established Arkansas Territory in 1819, it began the description of the territory “on” the Mississippi River.

The Mississippi River has never been static as the eastern boundary of Arkansas. With each flood and earthquake, the boundary changes, sometimes radically. A legal principle known as avulsion holds that when a sudden change takes land from one side of the river and places it on the other, the adjoining state does not gain land. The current map of Arkansas, therefore, reflects dozens of areas of Arkansas that are now east of the Mississippi River and are accessible by land only from Tennessee or Mississippi. Because of changes in the Mississippi River, Congress authorized Arkansas and Tennessee in 1909 to settle the boundary by agreement. But it still changes, and at least nine Supreme Court decisions have settled controversies relating to Arkansas’s eastern boundary. Except for parcels lying in other states, the eastern boundary now is the middle of the main channel of the Mississippi—the boundary established in 1836, when Arkansas was admitted into the Union.

Louisiana Boundary

Arkansas’s second boundary was also established before it became a state, when the Louisiana Purchase was divided in 1804 into the District of Orleans and the District of Louisiana. As a result, Arkansas’s southern boundary was established at latitude thirty-three degrees north. Orleans, south of the line, later became the state of Louisiana, and the southern part of the District of Louisiana (later known as the Louisiana Territory) became Arkansas.

Missouri Boundary

The first step in creating Arkansas’s north boundary occurred in 1813, when, as part of the Missouri Territory (formerly the Louisiana Territory, renamed in 1812), the territorial legislature of Missouri created Arkansas County for all the land between Louisiana and approximately thirty-six degrees north latitude, comprising all but a few northern counties of present-day Arkansas. Four years later, Missouri Territory residents began petitioning Congress for statehood and described the southern boundary of its proposed state as latitude thirty-six degrees, thirty minutes north. “The southern limit [of Missouri] will be an extension of the line that divides Virginia and North Carolina, Tennessee and Kentucky. …A front of three and a half degrees up on the Mississippi will be left to the South to form the territory of Arkansas, with the River Arkansas traversing its centre,” Missouri’s petitioners said. Their plan was to make room for three states (Arkansas, Missouri and Iowa), each having equal land fronting on the Mississippi River.

But what happened next is shrouded in mystery, confusion, and conflicting stories. The proposal for Missouri statehood would have left in Arkansas the area now known as the Missouri bootheel. John Hardeman Walker, a wealthy landowner whose portrait hangs in the public library in Caruthersville, Missouri, is generally credited as the man responsible for stealing the bootheel from Arkansas. He lived in the area, and when word spread that Missouri was seeking statehood, he and others persuaded the territorial legislature to include not only the bootheel but large parts of the Black and White River valleys in northern Arkansas, which today include all or part of seven Arkansas counties. While Walker is blamed for including the bootheel in Missouri, little written proof is found. Indeed, once the movement for Missouri statehood began, residents began petitioning Congress to form Arkansas Territory, and at least one petition described the north boundary as the thirty-sixth latitude between the Mississippi and St. Francis rivers and the thirty-seventh latitude from the St. Francis west, thus the proposal would give the bootheel to Missouri but extend Arkansas farther north to the outskirts of present-day Springfield, Missouri.

In late 1818, a Kentucky congressman proposed the territorial boundary of Missouri and Arkansas as the thirty-sixth latitude from the Mississippi west. The political maneuvering is not well recorded, but the act of Congress of March 2, 1819, creating Arkansas Territory defines the northern boundary as beginning on the Mississippi River at latitude thirty-six degrees north and running west to the St. Francis River, then up the river to latitude thirty-six degrees, thirty minutes north, and then west, thereby creating the Missouri bootheel. Therefore, the bootheel was established when Congress created Arkansas Territory, for it was two years later that Missouri was admitted to the union.

Oklahoma Boundary

From the time of the Louisiana Purchase, the western boundary of Arkansas was in dispute, and no one knew for sure where it was. Ultimately, the 1819 treaty with Spain established the western boundary for the Purchase, so the boundary for the part that would become Arkansas Territory included all of present-day Oklahoma except the three westernmost counties in Oklahoma’s panhandle.

Settlers barely had time to build homes in Arkansas before the push began east of the Mississippi River to remove Native Americans. Just five years after the Louisiana Purchase, the first of nearly a dozen boundaries was established with the Indians for what would become Arkansas’s western border. A November 10, 1808, treaty established the boundary with the Osage Nation due south of Fort Clark on the Missouri River to the Arkansas River, leaving present-day Washington, Benton, Crawford, and parts of other northwest Arkansas counties out of Arkansas and inside the Osage Nation. Future president Andrew Jackson was the United States’s representative at the October 18, 1820, Treaty of Doak’s Stand in Mississippi, when the Choctaw reluctantly agreed to move to Arkansas. Jackson, however, paid little attention to the map and agreed to transfer to the Choctaw Nation a large part of southwest Arkansas that already had been surveyed and sold by the U.S. government to settlers. The south end of the Choctaw boundary, although not surveyed for years, ended on the Red River at a point that is now the southeast corner of Oklahoma. The line caused an uproar resulting in several other treaties, one of which left Fort Smith (Sebastian County) in Oklahoma.

Congress’s first attempt to set the western boundary for Arkansas Territory was in 1824, when—assuming the Choctaw would agree to change its 1820 treaty—it established the boundary forty-five miles west of Fort Smith. An 1828 treaty with the Cherokee Nation established the present Arkansas border. The western boundary was described as “commencing on the Red River at the point where the eastern Choctaw line strikes said river, and run due north with said line to the River Arkansas thence in a direct line to the southwest corner of Missouri.”

But that was not the final word. When Arkansas applied for admission to the Union, its proposed western border again was described as forty-five miles farther west, thereby causing Choctaw opposition to Arkansas’s admission. The act of Congress granting statehood used the Cherokee treaty description for the western Arkansas border. The dispute with the Choctaw continued. Because Arkansas and the Choctaw Nation seceded during the Civil War, boundaries were again subject to dispute when both reapplied for admission to the Union. The Supreme Court settled the dispute in 1886, fifty years after Arkansas became a state, by requiring the United States to pay the Choctaw for lands taken to establish the present boundary.

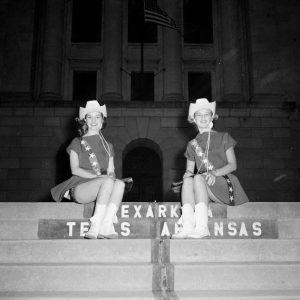

Texas Boundary

For many years, Arkansas’s border was the international boundary between the United States and first Spain, then Mexico, then the Republic of Texas. The February 28, 1819, treaty between the United States and Spain established the international border as a line running due north from the Sabine River in Louisiana to the south bank of the Red River and then west along the river. Thus, all of the Red River was in the United States. But it is one thing to establish a boundary on paper and another to locate it on the ground—it was not surveyed for many years. At one time, Arkansas Territory consisted of all or part of thirteen present Texas counties, and the Miller County courthouse was about fifty miles west of Texarkana. The uncertainty of the boundary led to near war with Spain when the Spanish army, claiming part of Arkansas in the Red River valley north of present-day Texarkana, stopped President Thomas Jefferson’s southern exploration of the Louisiana Purchase, led by Thomas Freeman and Peter Custis. Jefferson’s humiliation by Spain over the border dispute in Arkansas caused the government to downplay the Freeman-Custis expedition, leaving all of the glory of the exploration of Louisiana to the Lewis and Clark expedition.

Ultimately, the border was established by a survey completed five years after statehood, pursuant to an 1838 treaty with the Republic of Texas confirming prior treaties with Mexico and Spain. Today, the Texas border begins at the northwest corner of Louisiana and runs north to the south bank of the Red River, then west on the south bank of the river to the Oklahoma line.

For additional information:

Everett, Derek R. “On the Extreme Frontier: Crafting the Western Arkansas Boundary.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 62 (Spring 2008): 1–26.

Flores, Dan L. The Freeman & Custis Expedition of 1806. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1984.

Hagge, Patrick D. “Arrested Development: Historical Impacts and Influences on the Boundary of Arkansas.” Journal of the Fort Smith Historical Society 42 (September 2018): 20–29.

Shoemaker, Floyd C. Missouri’s Struggle for Statehood 1804–1821. New York: Russell & Russell, 1969.

White, Lonnie J. “Disturbances on the Arkansas-Texas Border, 1827–1931.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 19 (Summer 1960): 95–110.

John P. Gill

Little Rock, Arkansas

Arkansas Counties Map, 1819

Arkansas Counties Map, 1819  Arkansas Counties Map, 1836

Arkansas Counties Map, 1836  Arkansas Counties Map, 1850

Arkansas Counties Map, 1850  Arkansas Counties Map, 2005

Arkansas Counties Map, 2005  Arkansas-Texas State Line

Arkansas-Texas State Line  Arkansas-Texas State Line

Arkansas-Texas State Line  Blues Highway

Blues Highway  Choctaw Nation Border Marker

Choctaw Nation Border Marker  Dual State Monument

Dual State Monument  Mississippi River

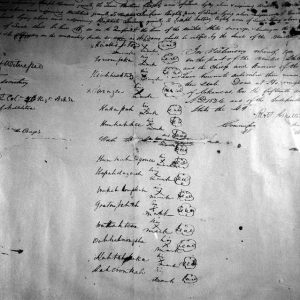

Mississippi River  Quapaw Treaty of 1824

Quapaw Treaty of 1824  U.S. Map, circa 1820

U.S. Map, circa 1820

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.