Abstract

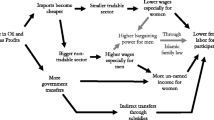

Several studies suggest that the extractive industry has negative consequences for gender equality despite the often positive growth impact of natural resources. We re-examine this claim at the sub-state level in sub-Saharan Africa and argue that we need to differentiate between ownership arrangements in the extractive industry. To test our argument on the gender dimension of the resource curse, this article employs unique data on the control rights of minerals within sub-Saharan countries as well as data from Afrobarometer and Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS). Our quantitative analyses explore how international vs. domestic ownership of copper, diamond and gold mines affects the labor market integration of females and intimate partner violence. The regression results suggest in line with our theoretical expectations that gender-specific structural labor market shifts within extractive industries are contingent on mineral control rights. Our models show that within mining areas, only domestic ownership reduces male unemployment. While domestic mining seems to reinforce the traditional male breadwinner model, internationally owned mineral extraction induces structural labor market changes: women abandon subsistence farming activities and migrate to the service sector. Our results further indicate that this shift of traditional gender roles within rural mining areas is associated with less intimate partner violence.

Zusammenfassung

Mehrere Studien deuten darauf hin, dass sich der Bergbau von wertvollen Mineralien trotz seiner positiven Wachstumseffekte negativ auf die Gleichstellung der Geschlechter auswirkt. Wir überprüfen diese Behauptung für Subsahara-Afrika und argumentieren, dass wir zwischen den Eigentumsverhältnissen in der mineralgewinnenden Industrie unterscheiden müssen. Um diese Hypothese zur Geschlechterdimension des Ressourcenfluches zu testen, verwendet dieser Artikel einen neuen Datensatz zu den Kontrollrechte in der rohstoffgewinnenden Industrie sowie Daten aus Afrobarometern sowie den Demographie- und Gesundheitsbefragungen (DHS). Unsere quantitativen Analysen untersuchen, wie sich der internationale vs. inländische Besitz von Kupfer-, Diamant- und Goldminen auf die Arbeitsmarktintegration von Frauen und die interpersonelle Gewalt auswirkt. Die Regressionsergebnisse deuten im Einklang mit unseren theoretischen Erwartungen darauf hin, dass geschlechtsspezifische strukturelle Arbeitsmarktveränderungen im Bergbau von den Eigentumsrechten in diesem Sektor abhängen. Unsere Modelle zeigen, dass Bergbaugebiete mit inländischen Eigentümern eher eine Reduktion der Arbeitslosigkeit von Männern erfahren. Während ein von Inländern dominierter Minensektor das traditionelle männliche Broternährer-Modell zu stärken scheint, führt der international kontrollierte Bergbau zu strukturellen Arbeitsmarktveränderungen: Frauen verlassen die Subsistenzwirtschaft und wandern in den Dienstleistungssektor ab. Unsere Ergebnisse zeigen weiterhin, dass diese Verschiebung der traditionellen Geschlechterrollen in ländlichen Bergbaugebieten mit einer Reduktion der Gewalt zwischen Intimpartnern verbunden ist.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Local content laws require foreign companies to use the local labor force and local firms for the procurement of goods and services (see Tordo et al. 2013).

We have deliberately chosen round six because our data on mining control rights cover the period 1997–2015.

We check the robustness of our results using different time spans (5- and 6‑years periods) when calculating the number of active mines within buffer zones. All results remain qualitatively unchanged.

This variable is based on the question “Do you have a job that pays a cash income? If yes, is it full-time or part-time? If no, are you presently looking for a job?” Note that Afrobarometer also asks individuals whether they are unemployed and not actively looking for a job (which is commonly the case for e.g. housewives or women working in subsistence farming).

The dummy variable corruption equals 1 if the interviewee thinks that most or all of local government councilors are corrupt.

The variable living conditions equals 1 if respondents consider their current living conditions as being better or much better than the conditions of others in their country.

The district information was assigned to the coordinates of each survey cluster using GIS software and spatial data from the Global Administrative Unit Layers (GAUL). Following the strategy of Fjelde and Østby (2014), we matched the coordinates from DHS survey clusters with district information from GAUL polygons using the software QGIS. The district information was then assigned to surveyed households through the DHS cluster identifier variable.

These kinds of measures were not collected by Afrobarometer.

These tables are available upon request.

The appendix provides an overview of distribution of the independent mine ownership variables. Out of 4388 sampled DHS districts, only a limited number has hosted mining activities during the period under consideration. The majority of the mines in our sample are internationally controlled. Furthermore, most respondents only experience the impact of one mine in their district.

When calculating averages for only those observations that are non-missing in model 4 and 6, these percentages are slightly higher.

References

Adewuyi, Adeolu O., T. Ademola Oyejide, (2012) Determinants of backward linkages of oil and gas industry in the Nigerian economy. Resources Policy 37(4):452-460

Aizer, Anna. 2010. The gender wage gap and domestic violence. American Economic Review 100:1847–1859.

Amendolagine, Vito, Amadou Boly, Nicola Daniele Coniglio, Francesco Prota, and Adnan Seric. 2013. FDI and local linkages in developing countries: Evidence from sub-Saharan Africa. World Development 50:41–56.

Aragón, Fernando M., and Juan Pablo Rud. 2016. Polluting industries and agricultural productivity. Evidence from mining in Ghana. Economic Journal 126:1980–2011.

Atkinson, Maxine P., Theodore N. Greenstein, and Molly Lang Monahan. 2005. For women, breadwinning can be dangerous. Gendered resource theory and wife abuse. Journal of Marriage and Family 67:1137–1148.

Bagshaw, Eryk. 2017. The Australian companies mining $40 billion out of Africa. The Sydney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/the-australian-companies-mining-40-billion-out-of-africa-20170906-gyc6t0.html. Accessed 25 June 2018.

Bebbington, Anthony, Denise Humphreys Bebbington, Jeffrey Bury, Jeannet Lingan, Juan Pablo Muños, and Martin Scurrah. 2008. Mining and social movements. Struggles over livelihood and rural territorial development in the Andes. World Development 36:2888–2905.

Benshaul-Tolonen, Anja. 2018. Endogenous gender norms: evidence from Africa’s gold mining industry. OxCarre Research Paper (working paper).

Benshaul-Tolonen, Anja, and Sarah Baum. 2019. Structural transformation, extractive industries and gender equality. Working Paper.

Benshaul-Tolonen, Anja, Putnam Chuhan-Pole, Andres Dabalen, Andreas Kotsadam, and Aly Sanoh. 2019. The local socioeconomic effects of gold mining: evidence from Ghana. Working Paper.

Bhanumathi, K. 2009. The status of women affected by mining in India. In Tunnel vision, women, mining and communities, ed. Ingrid MacDonald, Claire Rowland, 20–24. Fitzroy: Oxfam Community Aid Abroad.

Brain, Kelsey A. 2017. The impacts of mining on livelihoods in the Andes. A critical overview. Extractive Industries and Society 4:410–418.

Bryson, Judy C. 1981. Women and agriculture in sub Saharan Africa. Implications for development (an exploratory study). Journal of Development Studies 17:29–46.

Cane, Isabel, Amgalan Terbish, and Onon Bymbasuren. 2013. Mapping gender based violence and mining infrastructure in Mongolian mining communities. International Mining for Development Centre. IM4DC Action Research Final Report.

Choi, Susanne Y.P., and Kwok-Fai Ting. 2008. Wife beating in South Africa. An imbalance theory of resources and power. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 23:834–852.

Coderre-Proulx, Mylène, Bonnie Campbel, and Issiaka Mandé. 2016. International migrant workers in the mining sector. International Labour Office, Sectoral Policies Department, Conditions of Work and Equality Department. Geneva: ILO.

Conroy, Amy A. 2014. Marital infidelity and intimate partner violence in rural Malawi. A Dyadic Investigation. Archives of Sexual Behaviour 43(7):1303–1314.

Cools, Sara, and Andreas Kotsadam. 2017. Resources and intimate partner violence in sub-Saharan Africa. World Development, 95:211–230.

D’Alessio, Stewart J., and Lisa Stolzenberg. 2010. The sex ratio and male-on-female intimate partner violence. Journal of Criminal Justice 38:555–561.

Dancygier, Rafaela M., Naoki Egami, Amaney Jamal, and Ramona Rischke. 2019. Hating and mating: fears over mate competition and violent hate crime against refugees. SSRN https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3358780.

Eftimie, Adriana, Katherine Heller, and John Strongman. 2009. Gender dimensions of the extractive industries. Mining for equity. Working paper, extractive industries and development series #8. Washington D.C: World Bank.

Eller, Stacy L., Peter R. Hartley, and Kenneth B. Medlock III. 2011. Empirical evidence on the operational efficiency of National Oil Companies. Empirical Economics 40:623–643.

Fessehaie, Judith. 2012. What determines the breadth and depth of Zambia’s backward linkages to copper mining? The role of public policy and value chain dynamics. Resources Policy 37:443–451.

Fjelde, Hanne, and Gudrun Østby. 2014. Socioeconomic inequality and communal conflict, A disaggregated analysis of sub-saharan Africa, 1990–2008. International Interactions 40:737–762.

Galdino, Katia M., Moses N. Kiggundu, Carla D. Jones, and Sangbum Ro. 2018. The informal economy in pan-Africa: review of the literature, themes, questions, and directions for management research. Africa Journal of Management 4:225–258.

Goode, William J. 1971. Force and violence in family. Journal of Marriage and the Family 30:624–636.

Gurr, Ted Robert. 1970. Why men rebel. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hartley, Peter, and Kenneth B. Medlock III. 2008. A model of the operation and development of a national oil company. Energy Economics 30:2459–2485.

Heath, Rachel. 2014. Women’s access to labor market opportunities, control of household resources, and domestic violence: evidence from Bangladesh. World Development 57:32–46.

Hinton, Jennifer J., Barbara E. Hinton, and Marcello M. Veiga. 2006. Women in artisanal and small scale mining in Africa. In Women miners in developing countries: Pit women and others, ed. Kuntala Lahiri-Dutt, 209–226.

Infomine. 2013. Mine sites, Major mining operations around the world. http://www.infomine.com/minesite/. Accessed 29 Mar 2018.

Jenkins, Katy. 2014. Women, mining and development. An emerging research agenda. Extractive Industries and Society 1:329–339.

Knutsen, Carl H., Andreas Kotsadam, Eivind Hammersmark Olsen, and Tore Wig. 2016. Mining and Local Corruption in Africa. American Journal of Political Science 61:320–334.

Kotsadam, Andreas, and Anja Tolonen. 2016. African mining, gender, and local employmen. World Development 83:325–339.

La Porta, Rafael, and Florencio López-de-Silanes. 1999. The benefits of privatization, evidence from Mexico. Quarterly Journal of Economics 114:1193–1242.

Lahiri-Dutt, Kuntala. 2006. Mainstreaming gender in the mines. Results from an Indonesian colliery. Development in Practice 16:215–221.

Lucas, Robert. 1987. Emigration to South Africa’s Mines. American Economic Review 77:313–330.

Macmillan, Ross, and Rosemary Gartner. 1999. When she brings home the bacon: labour-force participation and the risk of spousal violence against women. Journal of Marriage and the Family 61:947–958.

McCloskey, Laura Ann. 1996. Socioeconomic and coercive power within the family. Gender and Society 10:449–463.

Mohan, Giles. 2013. Beyond the enclave, towards a critical political economy of China and Africa. Development and Change 44:1255–1272.

Morris, Mike, Raphael Kaplinsky, and David Kaplan. 2012. ‘One thing leads to another’—commodities, linkages and industrial development. Resources Policy 37:408–416.

Muchadenyika, Davison. 2015. Women struggles and large-scale diamond mining in Marange, Zimbabwe. The Extractive Industries and Society 2(4):714–721.

Mususa, Patience. 2010. Getting by. Life on the Copperbelt after the privatisation of the Zambia Consolidated Copper Mines. Social Dynamics 36:380–394.

Papke, Leslie E., and Jeffrey M. Wooldridge. 2008. Panel data methods for fractional response variables with an application to test pass rates. Journal of Econometrics 145:121–133.

Radtke, K.M., M. Ruf, H.M. Gunter, K. Dohrmann, M. Schauer, A. Meyer, and T. Elbert. 2011. Transgenerational Impact of Intimate Partner Violence on Methylation in the Promoter of the Glucocorticoid Receptor. Translational Psychiatry 1:e21.

Ross, Michael. 2008. Oil, Islam, and women. American Political Science Review 102:107–123.

Ross, Michael. 2012. The oil curse. How petroleum wealth shapes the development of nations. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Taylor, John. 1990. The reorganization of mine labor recruitment in Southern Africa. Evidence from Botswana. International Migration Review 24:250–272.

Tordo, Silvana, Michael Warner, Osmel Manzano, and Yahya Anouti. 2013. Local content policies in the oil and gas sector. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

True, Jacqui. 2012. The political economy of violence against women. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

UNECA. 2011. Minerals and Africa’s development. The international study group report on Africa’s mineral regimes. Addis Ababa: United Nations Economic Commission for Africa.

Velásquez, Teresa A. 2012. The science of corporate social responsibility (CSR): contamination and conflict in a mining project in the southern Ecuadorian Andes. Resources Policy 37:233–240.

Victoroff, Jeff, Samir Quota, Janice R. Adelman, Barbara Celinska, Naftali Stern, Rand Wilcox, and Robert M. Sapolsky. 2010. Support for religio-political aggression among teenaged boys in Gaza: Part I: psychological findings. Aggressive Behavior 36:219–231.

Wegenast, Tim, and Gerald Schneider. 2017. Ownership matters: natural resources property rights and social conflict in Sub-Saharan Africa. Political Geography 61:110–122.

Wegenast, Tim, Arpita Khanna and Gerald Schneider. 2019a. The Micro-Foundations of the Resource Curse: Mineral Ownership and Local Economic Well-Being in Sub-Saharan Africa. Unpublished Working Paper, University of Konstanz.

Wegenast, Tim, Mario Krauser, Georg Strüver, and Juliane Giesen. 2019b. At Africa’s expense? Disaggregating the employment effects of Chinese mining operations in sub-saharan Africa. World Development 118:39–51.

Wilson, Jeffrey D. 2015. Understanding resource nationalism: economic dynamics and political institutions. Contemporary Politics 21:399–416.

Yyas, Seema, and Charlotte Watts. 2009. How does economic empowerment affect women’s risk of intimate partner violence in low and middle income countries? A systematic review of published evidence. Journal of International Development 21:577–602.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the editorial team of ZeFKo, guest editor Nils Weidmann and two anonymous reviewers for their guidance and comments on earlier versions of the article.

Funding

Financial support from the German Research Foundation (DFG), as part of the research project “Resource Management and Intrastate Conflict” (WE 4850/1-2), is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Caption Electronic Supplementary Material

42597_2019_19_MOESM1_ESM.docx

The online appendix shows the distribution of the ownership arrangements across mineral resources, individual countries and within proximity of Afrobarometer respondents. Moreover, we provide results on the robustness tests using linear fixed-effects models and narrower buffer zones.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Krauser, M., Wegenast, T., Schneider, G. et al. A gendered resource curse? Mineral ownership, female unemployment and domestic violence in Sub-Saharan Africa. Z Friedens und Konflforsch 8, 213–237 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42597-019-00019-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42597-019-00019-8