Profile: Muammar Gaddafi

- Published

Muammar Gaddafi is clinging to power in Libya amid violence and unrest, and the International Criminal Court has issued a warrant for his arrest for crimes against humanity. The BBC's Aidan Lewis profiles the Libyan leader.

Colonel Muammar Gaddafi is the longest-serving leader in both Africa and the Arab world, having ruled Libya since he toppled King Idris I in a bloodless coup at the age of 27.

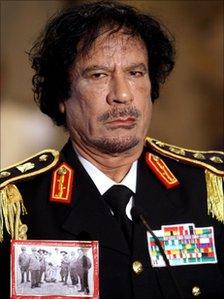

Known for his flamboyant dress-sense and gun-toting female body guards, the Libyan leader is also considered a skilled political operator who moved swiftly to bring his country out of diplomatic isolation.

It was in 2003 - after some two decades of pariah status - that Tripoli took responsibility for the bombing of a Pan Am plane over the Scottish town of Lockerbie, paving the way for the UN to lift sanctions.

Months later, Col Gadaffi's regime abandoned efforts to develop weapons of mass destruction, triggering a fuller rapprochement with the West.

That saw him complete a transition from international outcast to accepted, if unpredictable, leader.

"He's unique in his discourse, in his behaviour, in his practice and in his strategy," says Libya analyst Saad Djebbar.

"But he's a shrewd politician, make no mistake about that. He's a political survivor of the first order."

Bedouin roots

Muammar Gaddafi was born in the desert near Sirte in 1942.

In his youth he was an admirer of Egyptian leader and Arab nationalist Gamal Abdel Nasser, taking part in anti-Israel protests during the Suez crisis in 1956.

He first hatched plans to topple the monarchy at military college, and received further army training in Britain before returning to the Libyan city of Benghazi and launching his coup there on 1 September 1969.

He laid out his political philosophy in the 1970s in his Green Book, which charted a home-grown alternative to both socialism and capitalism, combined with aspects of Islam.

In 1977 he invented a system called the "Jamahiriya" or "state of the masses", in which power is meant to be held by thousands of "peoples' committees".

The Libyan leader's singular approach is not limited to political philosophy.

On foreign trips he has set up camp in a luxury Bedouin tent and been accompanied by armed female bodyguards - said to be considered less easily distracted than their male counterparts.

A tent is also used to receive visitors in Libya, where Col Gaddafi sits through meetings or interviews swishing the air with a horsehair or palm leaf fly-swatter.

Idiosyncratic

Benjamin Barber, an independent political analyst from the US who has met Col Gaddafi several times recently to discuss Libya's future, says the Libyan leader "sees himself very much as an intellectual".

"As a man he is surprisingly philosophical and reflective in his temperament - for an autocrat," he told the BBC News website.

"I see him very much as a Berber tribesman, somebody who came out of a culture informed by the desert, by the sand, and in some ways very atypical of modern leadership, and that's given him a certain endurance and persistence."

Col Gaddafi has long tried to exert his influence over the region and beyond.

Early on he sent his army into Chad, where it occupied the Aozou Strip in the north of the country in 1973.

In the 1980s, he hosted training camps for rebel groups from across West Africa, including Tuaregs, who are part of the Berber community.

More recently he has led efforts to mediate with Tuareg rebels in Niger and Mali.

'Mad dog'

The diplomatic community's rejection of Libya centred on Col Gaddafi's backing for a number of militant groups, including the Irish Republican Army and the Palestine Liberation Organisation.

US president Ronald Reagan labelled Libya's leader a "mad dog", and the US responded to Libya's alleged involvement in attacks in Europe with air strikes on Tripoli and Benghazi in 1986.

Col Gaddafi was said to be badly shaken by the bombings, in which his adopted daughter was killed.

Spurned in his efforts to unite the Arab world, from the 1990s Col Gaddafi turned his gaze towards Africa, proposing a "United States" for the continent.

He adopted his dress accordingly, sporting clothes that carried emblems of the African continent or portraits of African leaders.

At the turn of the millennium, with Libya struggling under sanctions, he began to bring his country in from the cold.

In 2003 the turnaround was secured, and five years later Libya reached a final compensation agreement over Lockerbie and other bombings, allowing normal ties with Washington to be restored.

"There will be no more wars, raids, or acts of terrorism," Col Gaddafi said as he celebrated 39 years in power.

Domestic challenges

At home, the Libyan leader presents himself as the spiritual guide of the nation, overseeing what he says is a version of direct democracy.

In practice, critics say, Col Gaddafi has retained absolute, authoritarian control.

Dissent has been ruthlessly crushed and the media remains under strict government control.

Libya has a law forbidding group activity based on a political ideology opposed to Col Gaddafi's revolution.

The regime has imprisoned hundreds of people for violating the law and sentenced some to death, Human Rights Watch says.

Torture and disappearances have also been reported.

In May 2011, the International Criminal Court's prosecutor, Luis Moreno-Ocampo, sought the arrest of Libyan leader and two others for crimes against humanity.

The prosecutor said that Col Gaddafi bore responsibility for "widespread and systematic attacks" on civilians.

Warrants for the arrest of Col Gaddafi's arrest, his son Saif al-Islam and chief of intelligence Abdullah al-Sanussi were issued in June.

Before the rebellion in Libya began, Col Gaddafi was thought to be preparing the ground for a transition.

But it remained unclear who might succeed such a dominant figure.

Speculation focused on one of his sons, Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, who built up an image as a modernising, reformist mediator with the West.

That image, as well as any hope of a peaceful transition, rapidly disappeared from view as the Gaddafi family closed ranks in the face of the uprising.