Burma’s newly installed government is trying to get foreign diplomats to refrain from using the name Rohingya, in the latest blow to the country’s heavily persecuted Muslim group. The move is an apparent bow to pressure from a small but influential ultra-nationalist movement that refuses to recognize the rights of the Rohingya people to belong in Burma.

A spokeswoman for Burma’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Aye Aye Soe, tells TIME that the government is “not objecting [to] the term [Rohingya] but requesting not to use it.” The suggestion was made during private “courtesy calls” between Aung San Suu Kyi — in her role as Minister of Foreign Affairs — and the U.S. Ambassador to Burma Scot Marciel, after the embassy had been targeted by Burmese over its use of the word. Protesters see the term — which means a person of Rohang, the old Muslim term for what is now Arakan state in western Burma — as conferring historical legitimacy on the Muslim presence in the country that is also known as Myanmar.

Though the historical origins of the term Rohingya are muddy, many Rohingya families have lived in western Burma for generations and the majority choose this term to describe themselves. However, during the 2014 census, the Rohingya were forced to identify themselves as “Bengali” — the official term for them — or they would not be registered. They are not recognized as one of the 135 official ethnic groups in the country, and nearly all of the 1.1 million Rohingya are denied citizenship and basic rights.

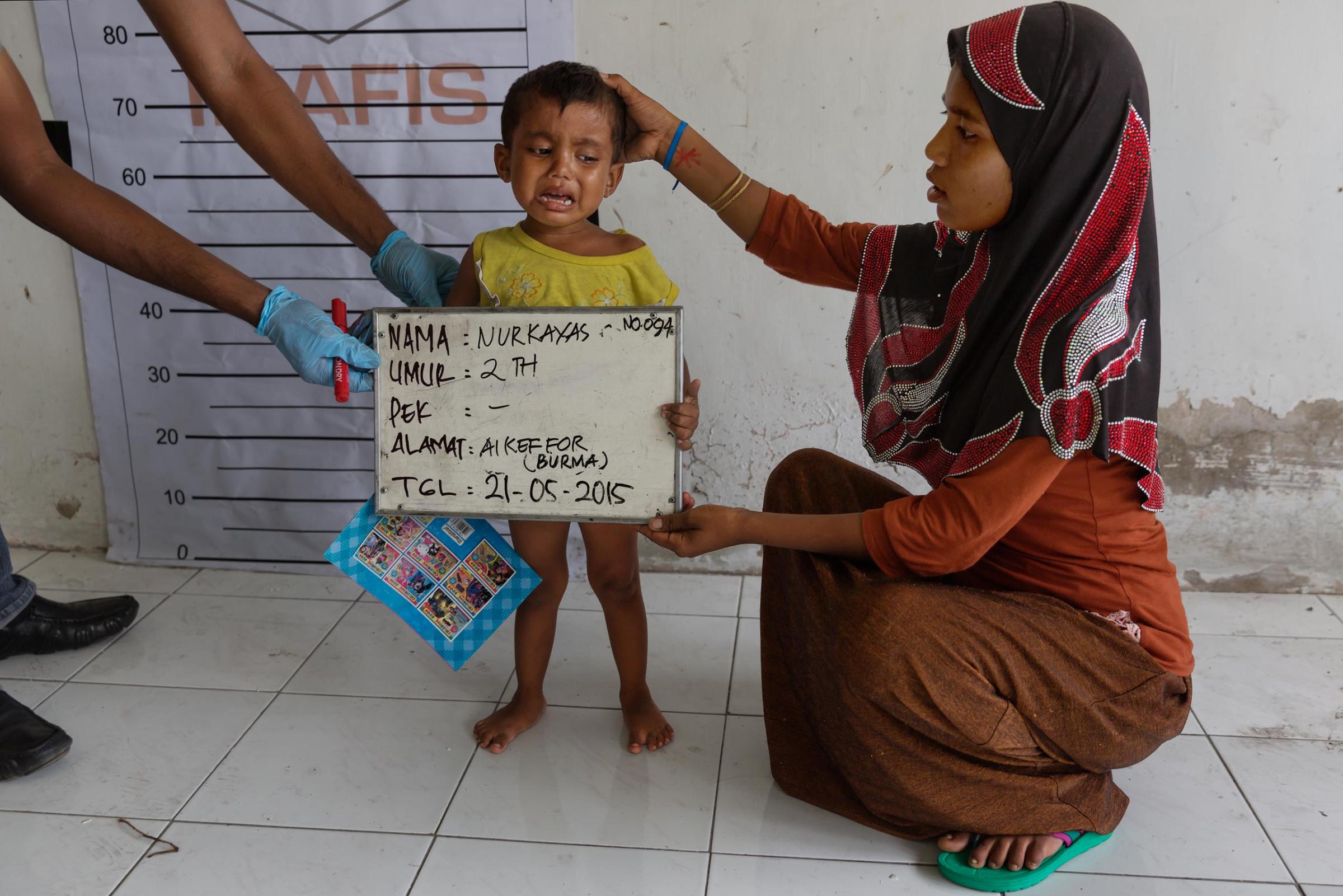

The U.N. considers the Rohingya, who reside near Burma’s border with Bangladesh, to be among the world’s most persecuted minorities, but in most of Burma they are viewed as dangerous interlopers. In western Arakan state, a spate of deadly riots beginning in 2012 between the local Buddhist population and the Muslim Rohingya claimed more than 100 lives and displaced some 140,000 people — mostly Rohingya. Many are still confined to squalid camps where they are denied freedom of movement, education and health care. Conditions are so dire that tens of thousands have fled by boat, undertaking perilous voyages in the hands of traffickers in the hope of finding refuge in Muslim-majority Malaysia or other Southeast Asian countries.

Read More: Burma’s Hard-Line Buddhists Are Waging a Campaign of Hate That Nobody Can Stop

While the international community has repeatedly urged the government to end persecution and allow the group to call themselves Rohingya if they wish, last week’s advisory signals that the county’s new government, led by Nobel laureate Suu Kyi, is not inclined toward concessions and will continue to scrub the term from official usage.

“Many Buddhists believe the name Rohingya is a political claim that they cannot agree to,” according to Ronan Lee, a researcher and former Australian lawmaker who has conducted extensive studies in Arakan state.

The Plight of the Rohingya by James Nachtwey

The fear among local Arakan communities appears to be that recognizing the rights of the Rohingya would open up Burma’s porous border with Bangladesh, and lead to a Muslim incursion in a devoutly Buddhist nation. These fears have been fueled by a burgeoning movement led by hard-line Buddhists, with the support of influential monks, who in recent years have spread pervasive rumors about the Muslim community. The movement even successfully lobbied for the passage of discriminatory laws restricting religious conversion and birth rates, buoyed by a popular belief that Muslims were having too many children and could eventually overtake the Buddhist population.

The issue is so sensitive that there was uproar in late April, when the U.S. embassy in Rangoon issued a statement after at least 22 people, including nine children, died in a boat accident, and expressed condolences to the victims’ families, “who local reports state were from the Rohingya community.”

Hundreds of hard-line nationalists, including Buddhist monks, responded with a protest at the embassy, calling on diplomats to stop using what they called a “fake term.” Marciel in turn told reporters that referring to the Rohingya by their preferred name was “not a political decision; it’s just a normal practice,” reiterating that “communities anywhere have the ability to decide what they should be called.”

Read More: Rohingya Survivors Speak of Their Ordeals as 139 Suspected Graves Are Found in Malaysia

His response didn’t satisfy the protesters, members of a nationalist group called the Myanmar National Network. The group says they will continue to protest until the Burmese government publicly condemns the use of the word by foreign officials.

The Rohingya, Burma's Forgotten Muslims by James Nachtwey

“The right to self-identification should not be controversial,” says Wai Wai Nu, a renowned Rohingya activist and former political prisoner, who is known as one of the few activists in Burma to speak up on behalf of the beleaguered minority. But the issue has become so volatile that some international actors believe it would best be put aside for pragmatic reasons.

Lee says that while the international community’s use of the term Rohingya has helped bring the issue to the world’s attention, within Burma it could be creating a “political roadblock that stands in the way of Arakan state’s Muslims gaining the human rights and citizenship they are entitled to.”

Read More: Burma’s Nowhere People

The Burmese government also sees other issues as more pressing. Last year, Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) party swept the polls in a landslide win and assumed power in April, taking over from a military-backed government after decades of authoritarian rule. But the new democratic government has inherited a host of problems including civil war, grinding poverty, rampant corruption and a dysfunctional bureaucracy.

“As a new government [we have] thousands of problems to deal with,” Win Htein, a member of the ruling party’s central committee, tells TIME, frustrated by the Rohingya controversy. “The Rohingya and [Arakan] state is just one of the problems.”

The international community maintains that the plight of the Rohingya is urgent; the U.N. special rapporteur on Burma, Yanghee Lee, has called on the new government to improve the Rohingyas’ living situation within the first 100 days of its term. So far the government has given no public indication that it is addressing the issue, and Win Htein says that “Aung San Suu Kyi is the only one” authorized to speak on it.

Read More: Who Is Htin Kyaw, Burma’s New President?

To the great disappointment of human-rights advocates, she hasn’t. David Mathieson, a senior researcher for Human Rights Watch in Burma, says that Suu Kyi’s silence on the issue could “sully her and her government’s reputation,” urging her to rescind her ministry’s request to diplomats.

“It will be hard for Suu Kyi to address the Rohingya issue if she refuses to refer to them by their name and continues to kowtow to extremists,” Mathieson says, “which is what her qualified public statements amount to.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com