Local

Construction/Destruction of Williamsburg Continues at Frantic Pace

To get a taste of how developers are conceiving the “modern” Williamsburg, take a look at the strange, Wizard of Oz-style Technicolor renditions at the North 8th Condos showroom on Bedford, or the billboards in front of the Toll Brothers construction sites on Kent. Better yet, log onto themodernwilliamsburg.com or northsidepiers.com and see the not-unsurprising profile, complete with Techno-light music, of the neighborhood’s future. Ever since New York dubbed Williamsburg the “New Bohemia,” that proverbial dream and nightmare has rapidly become reality. The sheer pace and breadth of new construction has led to public safety issues galore as developers with little or no oversight rip down smaller structures and build McCondos at a furious pace. Sometimes it seems like the ghost of Robert Moses donned some hipster sunglasses and started tearing up the neighborhood, leaving any Jane Jacobsian ideal of preserving the unique traits of a community in the rearview mirror of a Hummer.

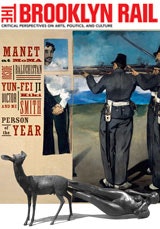

How developers envision the “New” Williamsburg.

How developers envision the “New” Williamsburg.After the massive re-zoning of the Williamsburg-Greenpoint area in the spring of 2005—which generated a great deal of self-congratulation from the City Council and Bloomberg administration—many of the promised benefits have been predictably slow to arise. Although ground has broken on a few of the towers to be built on the shore of the East River, the dream of a continuous boardwalk from the Williamsburg Bridge to the Newtown Creek seems a long way off. While there seems to be a small state park being built on the waterfront near North 8th Street, the plan for much larger green spaces also seems lost in the rumble of jackhammers and cranes (that have also taken down landmarks like the Old Dutch Mustard building; see the photo essay in the Streets section of this issue). And while affordable housing initiatives have also been slow to materialize, the most evident manifestation of the rezoning, as any resident can tell you, is luxury condo and other high-rise development.

Some of the building is baffling. Will that really be a hotel overlooking the BQE at Meeker and Withers? Are they really building a tall luxury condo building with a sweeping view of McGuinness Boulevard and pretty far from even the G Train? Do people really respond to sales lines like “Williamsburg. All grown up” and “It’s just different in Williamsburg” when they are looking to drop half a million on a new studio? It also begs the question: why are they breaking ground to build new condos at all? One Corcoran agent told me that the condo development at 55 Berry has been in a crisis, changed agents a couple of times, and slashed some of their prices by nearly a third last spring. Is it not a risky investment for developers to build blocks of “luxury” condos at all now?

Regardless, the high-rises are going up at a frantic pace. While many are modest in size, it’s clear that developers have also found lots at the edge of the rezoning, or in parcels that were overlooked, to lay foundations for tall buildings of the kind theoretically verboten by the contextual building restrictions fought for by the community and included in the rezoning. One spot that developers have supposedly planned 12 and 15 story towers is along Grand Street and Driggs Avenue, an area that, for unclear reasons, was not rezoned to restrict height limits. While the community can fight for rezoning these locations, such amendments can take upwards of a year. Meanwhile, once the foundations go in it becomes very difficult, if not impossible, to reverse the process (this was how the “finger” building and the towers on McCarren Park came about).

Doris Vila Licht, a coordinator for the Development Watchdog Project based in Williamsburg/Greenpoint, points out that even in more regulated areas developers find ways of exploiting vague rules and loopholes. “The message that developers are getting from the upper echelons of city government is that it’s OK to play fast and loose with regulations,” she says, “There are so many loopholes exploited. Some legally, some illegally. All we’re asking is that things are done by the book.” Any zoned area has a set of restrictions that upon closer examination become open to interpretation. This includes the use of “air rights” of adjoining lots as a way to build higher, or including insignificant “community space” as a way to gain more bulk. There are also a whole host of shenanigans to exploit the often vague delineations of “floor to area ratios” (FAR). “I asked city officials about FAR,” says Vila Licht, “but all they say is that they have to figure it out on a case by case basis. It’s very opaque.”

During the spasm of demolition and construction seen over the last year and a half, one of the biggest problems has been the enormous public safety concern as shoddy building demolition practices structurally comprise adjacent buildings and workers are put in danger by building in substandard safety conditions (not to mention code violations that may lead to compromised construction). According to Matthew Hennessy, a Williamsburg resident and construction worker for over two decades, “When looking in to jobsites while just standing on the street I can see they hardly ever fully abide by OSHA [Occupational Safety and Health Administration] standards. In fact, in over twenty years of doing construction I can count on one hand the times a city inspector for DOB [Department of Buildings] has stopped by my jobsites and I’ve never ever seen an OSHA agent.” The good news is that several City Council members are considering legislation to boost fines and require jail time for those who violate certain sections of the building code, in order to give some much needed teeth to the DOB. This would also mean that the NYPD could be utilized to enforce certain building codes, a move that many locals feel would dramatically change developers’ behavior.

The Bloomberg administration is imminently scheduled to unveil its 25-year goals for increasing municipal services in order to accommodate the rapid population growth predicted for New York City in the coming decades. But while some of that projected population growth will be white-collar professionals who can spend the money (or qualify for the mortgage) to buy condos that hover around a million bucks, the vast majority will be new immigrants as well as those arty folks who migrate to cities from around the country. So, while more housing is needed, the current condo construction boom is clearly helping only those at the upper end of the scale.

“This has been a neighborhood plagued by neglect for many years and it would benefit from thoughtful attention to the building laws,” says Vila Licht, who’s lived in the area since the 1980s. “Now there are a lot more kids, and maybe more of a feeling of community than ever before. It shouldn’t be threatened by a culture of greed running headlong into an unknown future and done in a way in which developers feel like they own everything.”