Poetry In Conversation

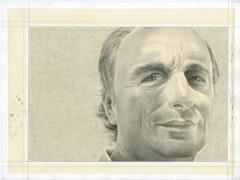

Marek Bartelik with René de Ceccatty

René de Ceccatty was born in Tunisia. His French family moved to France when he was six years old. A renowned novelist, essayist, playwright, and translator, his interests in Italian and Japanese literature have resulted in translations of such important writers as Ôé, Abé, Sôseki, Mishima, Tanizaki, Yûko Tsushima, Ogawa, Pasolini, Moravia, Leopardi, Saba, and Bonaviri. De Ceccatty lives and works in Paris, where Marek Bartelik sat down with him last March on the occasion of the release by Flammarion of his latest non-fiction book, Alberto Moravia, and his appearance on stage with the Italian actress Claudia Cardinale during a festival devoted to films based on Moravia’s books.

Marek Bartelik (Rail): Do you remember the moment when you became attracted to Italian poetry?

René de Ceccatty: It was after I saw Teorema, by Pier Paolo Pasolini. I watched the movie with a friend in a film festival during the Easter holidays in 1969. I immediately bought the book the movie was based on. At that time, I was writing a novel that combined a love story between two adolescent boys with a kind of religious revelation. I felt that Pasolini’s imagination was mine! The next year, I decided to study the Italian language at school, instead of taking English lessons. Our Italian teacher made us read Cesare Pavese’s poetry, diaries, short stories, and novels. The poem La morte verrà e avrà i tuoi occhi (Death will come and it will have your eyes) was a true discovery. Our teacher taught us how Petrarch and Cavalcanti influenced Ronsard and Du Bellay in France. She explained the rules of dolce stil nuovo. I thought that the land of poetry was Italy. But the real beginning of my “becoming Italian” happened in Perugia, where I spent a month during the summer of 1970. I should say my “becoming myself,” as well, because I was writing a lot, feeling that I would like to dedicate my life to writing.

Rail: When we talked about Pasolini some time ago, you mentioned that you wrote to him when you were a teenager and that recently your letters were discovered in his archives in Rome.

Ceccatty: I wrote to him when I was 18 years old, almost immediately after I saw Teorema and read his novel. In my letter, written in Italian, I asked him if I could send him my novel I’d just finished. He answered immediately: yes, he would like to read it, but he apologized in advance for not being a good judge of my literary qualifications because he did not know French well enough. On February 26, 1970, I sent my manuscript with another letter. I can be very precise, because a young Italian writer found the second letter and my manuscript 17 years later in his archives and sent them back to me.

Perhaps it could be interesting to cite fragments of my letter, rather than just paraphrasing it. Here they are:

Dear Pier Paolo Pasolini, I am really thrilled to write to you in Italian. You know that it is not my mother tongue, and I know, as far as I am concerned, that seeing one’s own language misused by a foreigner is not very pleasant…Teorema is the most beautiful movie I have ever seen and the novel (did you write it before the film or after?) revealed to me the beauty of Italian language and the richness that words contain when the writer focuses on literary structure. L’Enfant unique [The Only Child, that is the title of my novel] is the story of a mystic revelation.

I described my novel:

The real torments of my main character (Yves) spring from how to express love. He thinks he is unconventional compared to others. He is convinced that he must accomplish some task, because he does not understand how to touch other people... When he is alone with his friend Robert on the road, he yearns to reach a union with him, but he fails. He hopes that his faith in God, the rites of the church, will bring him a real union with other men and with the Earth. When he meets a man who understands him—a priest—he realizes that he behaves as if he is on stage when he lives with another man. In Yves’s earthly feelings, God reveals the purity of his attachments. God makes him discover earthly things in a new way.

It is very strange for me to read this letter now. My novel as summed up in this letter resembles not only the plot of an old Graham Greene novel, but the early diaries of Pasolini himself, which I could not have known at that time, because they were published by his cousin, Nico Naldini, only many years later, after Pasolini’s death. I guess Pasolini’s nature and mine were almost the same. We were very similar teenagers, but, of course, living in two different periods of history, before World War II for him, and before 1968 for me. We had similar ideas about sex and religion.

Rail: “Sex and religion”—this is a very explosive issue nowadays. Could you explain how you understand this connection?

Ceccatty: I differentiate between “sex and religion” and “sex and mysticism.” The first one is related to organized religions. There is a strong connection between sex and Catholicism. When I took religion classes, I was surprised how often the priests talked about sex. In confession, we were obliged to speak about our sexual lives. I don’t say that sexuality was unknown to me at that time, but it was very different from that which the priests were talking about. My sexuality was difficult to describe, because it was just a fantasy with no action and no pleasure, except for one traumatic event: I was about 8-years-old when an older boy (of about 16 or 18) assaulted me sexually. He didn’t exactly rape me; in fact, he was gentle and sweet during his sexual play. The whole event was very strange, almost poetic. At that time I did not understand what exactly had happened; he seemed to belong to another planet, another world. He was a stranger; I was playing with my young cousin in a vineyard near my house. Why he chose me remains a mystery. He appeared like a character in one of William Faulkner’s novels or in “The Encounter,” a very disturbing story from James Joyce’s Dubliners. Back then I did not make any connection between the sexual interests of the priests and my particular experience. However, I realized that a certain type of sexuality was an obsession for some Catholic priests.

The relationship between sex and mysticism is very different. They both require a complete commitment to someone else, either another person or another way of living. A search of the inner self and illumination occurs in an encounter. That was the reason why I was attracted to Pasolini’s Teorema. Other writers wrote about it as well—D.H. Lawrence of course, as well as Saint Teresa of Avila and Saint John of the Cross. Those two saints created extraordinary poems about God, desire, flesh, faith, and sacred marriage. But their poetry has little to do either with Catholicism or the Pope, or the sexual frustration of priests.

Rail: Do you feel a similar affinity with Yukio Mishima, another writer whose books you have translated into French?

Ceccatty: With Mishima things are very different. Ryôji Nakamura and I, we have translated two of Mishima’s books, his great “gay novel” Forbidden Colors (Kinjiki) and a collection of early short stories. Mishima was an excellent writer, with a superior intelligence and a very deep understanding of the culture of his time. But his personality does not interest me, and I don’t identify with him and his world at all. He was a married man, very hypocritical, with a double life: a middle class wife and young male lovers. His admiration for the army, for the empire, and his right-wing sympathies, are anathema to me. But his way of describing the human mind, behavior, social life, as well as his mastering of style and language, are exceptional.

My favorite Japanese writer is Natsume Sôseki (1867–1916). We translated five of his novels, as well as a collection of lectures and conferences. His writings interest me immensely. In the way he perceived and described inner and social life, Sôseki was as innovative for Japanese literature as Henry James was for American and British, and Marcel Proust for the French novel.

We have also translated books by the Nobel Prize winner Kenzaburô Ôé (and we did it before he won the prize), Kôbô Abe, and Tanizaki. As much as I enjoy contemporary writers—for instance, Hitonari Tsuji, Kazumi Yumoto, and Nao-Cola Yamazaki—because their modern style is very easy for me to understand and to read, I feel particularly close to classical Japanese literature, such as the 10th century Izumi-shikibu Diary or Tosa Diary. The ancient Japanese writers teach me a lot about the relationship between psychology and poesis.

Rail: How do you collaborate on your translations with Ryôji Nakamura?

Ceccatty: Ryôji currently lives in Japan, after 25 years in France, so we work using Skype with webcam. Each of us has the same book in front of him when we are translating together. Of course, it is easier to understand the original for Ryôji. We read in Japanese loudly first (I can read Japanese, but when I don’t understand an ideogram, Ryôji tells me how it should be read and what it means), then we look for the right word or words in French, followed by the equivalent sentences and expressions. After we agree on the choice of words and sentence structure, together we come up with the final version. I write it down, e-mail it to Japan, and he further corrects it if necessary. When I work with him I feel that I am reaching something very special within me, in my inner life, my relationship with literature and the Japanese language.

Rail: Your range of literary interests is exceptionally vast, spanning continents, countries, and cultures. Women writers also occupy an important place in it.

Ceccatty: I feel very close to women writers. I wrote a book on the first Italian feminist, Sibilla Aleramo, and another one on Violette Leduc, a “female Jean Genet,” as she was once described. I feel close to Marguerite Duras, Nathalie Sarraute, and the French Canadian Marie-Claire Blais. As a publisher, I publish the work of many women, as well as gays. I enjoy discussing literature and life with my women and gay friends. For me a gay is not a “different person” who belongs to a sexual minority. It might surprise you, but I think that a gay writer is someone who is more sincere, more adult, has a deeper and more complete relationship with the world than straight people. A straight writer, it seems to me, often ignores the essential diversity of humanity. But “gay” and “straight” are not satisfying labels, inappropriate for classical writers. It is simply absurd to say that Michelangelo, Shakespeare, Horace Walpole, or Henry James were gay, or even that Proust was gay. They just knew what love between two men or two women means. Currently, I am writing a novel about the Italian poet and philosopher Giacomo Leopardi (1798–1837). His greatest love was for his male friend Antonio Ranieri. But they probably had no sex. Sex was not the most important thing in their relationship; accepting their love was. The main thing was to be conscious of one’s feelings, rather than fighting them.

Rail: Various events from your life have played an important role in your novels. Could you talk about the way they shape your narrative and define your identity as a writer?

Ceccatty: I write only when I feel a true necessity to do so. I write when I need to help myself, not to survive—because I know that writing does not give that kind of support—but to understand myself. So every time I feel at a loss, every time a deep crisis happens in my life, I start writing. I don’t know if my action will result in a book, but I have to write and explain those very dark or very powerful moments. Working on my very first book, Personnes et personnages, which I wrote between 1969 and 1975, I dealt with questions about my childhood, sexual identity, my family’s departure from Tunisia. Having very strong memories and images still present in my mind, and experiencing my old anguishes, I described them in writing in a theatrical fashion. To do so, I used myths, the lives of the saints, Latin and Greek legends. Writing in such a way was very natural and clear to me, but the book ended up being quite odd, full of poems, descriptions of dreams and paintings, dialogues, fragments of diaries, and philosophical analysis. Although I wasn’t intending to recount my life, still the book is full of events from it—disguised as myths. With a more mature sexual and sentimental life, I wrote with growing directness. After I signed my first publishing contract, I felt more secure and self-confident. I put together two different love stories in one book, which was my second one, written partly during my stay in Japan between 1977 and 1979.

After my return from Japan, I tried to write another type of story, but I experienced writer’s block when I attempted to make it about Japan. So, instead, I wrote my first historical novel about Saint Francis Xavier’s travels from Portugal to India and Japan. When I wrote about him (L’extrémité du monde) or, later, when I wrote about Horace Walpole (L’or et la poussière) or Violette Leduc (La sentinelle du rêve), Galileo, Maria Callas, and other real characters (Le mot amour), I felt as if I was writing about myself.

But the strongest literary experiences, and the most difficult ones, occurred when I decided to write directly about my life. L’accompagnement tells a story of a friend who died from AIDS. Aimer and the next five novels (Consolation provisoire, L’éloignement, Fiction douce, Une fin, and L’Hôte invisible), are about friendship and love. But I decided not to publish Un père, which was a direct account of my relationship with a divorced father. Because the book was so personal, I gave my manuscript to him and asked if he objected to having it published. He could not make up his mind. I suspected that he could not bear seeing it published, so I decided not to, despite the fact that the book was already at the galley proof stage and had even been sent to critics for review. I asked my publisher not to print it. Antoine Gallimard understood and accepted my reasons.

It is impossible for me to make someone unhappy with my writings. My identity as a writer cannot impose itself against life and, above all, another person’s life. I know that it seems shocking for some other writers and artists, but I don’t think that we have the right to harm anybody with our art.

Rail: Do you have a particular interest in “gay” or “queer” literature?

Ceccatty: I don’t have an exclusive interest in gay, or queer, writers. As I mentioned earlier, Sôseki is one of my favorite authors of all time. And most of the great Japanese writers I like, read, and translate are straight. I have just written a biography of Alberto Moravia, who adored women, but who was totally gay-friendly. Pasolini was his close friend. In fact, Moravia wrote many novels and short stories, especially his last one a few days before he died at 83, about gay emotions. Still, I think that sexuality builds and determines a writer’s personality and, more generally speaking, everyone’s personality, sensibility, and perception. Important for being gay is the fact that it forces one to be true to himself or herself, to construct an honest identity, and to fight against social hypocrisy. It is a liberating experience that helps to understand others and differentiate between truths and lies in human behavior. That’s the reason why I like gay writers E.M. Forster, James Baldwin, Edmund White, Peter Cameron, Stephen McCauley. Obviously, there isn’t just one kind of gay people, as sexuality differs from person to person. There are other gay writers I don’t like, because I think that as writers they are shallow. Some can be vulgar. The main thing for me in writing is sincerity; I look for truth on both a personal level and in relations between people. Being gay may prevent one from being fake, but it is not always so.

Rail: You have many friends who are visual artists and your books contain some beautiful passages about paintings and painters.

Ceccatty: One example: in L’Hôte invisible, I tell a story similar to the one in my unpublished novel, but using a painting made by an unknown Slovenian painter of the 19th century, Josef Tominz. In that painting, the main character is absent. It portrays three women, drinking tea on a balcony; they are looking at us, but they appear to watch someone “off stage.” This invisible presence is like the man I loved and wrote about—but who forbade me to publish Un père. My literary reaction to this kind of blackmail offers perhaps the best answer to your question about the use of my life in my books and how my novels “shape my identity.”

Rail: You are a highly accomplished playwright. What is your relationship to theater?

Ceccatty: I wrote my first tragedy at the age of 15. In 1968, when I was 16, I wrote another play called Frühling (“spring” in German), which I performed with two female friends the next year during and right after the so-called Students’ Revolution. The plot is difficult to sum up: it is a kind of Ionesco or Beckett, expressing the impact of power and language on us, and the anguish before the unknown. We performed it in two theaters in Montpellier and in a bar in Avignon, where I rented a backroom during the 1969 Theater Festival. 17 performances in total. I remember our best performance was on July 21. Everybody was waiting for the first images of men walking on the moon, which was scheduled for broadcasting on French television at 2 or 3 AM. Waiting to witness that historic moment, many people came to see us in my play (our backroom was incredibly crowded!—for the first and last time…). I appeared on stage as an actor only once afterwards, in the Ionesco play Jacques ou la soumission.

My involvement with theater changed dramatically after I met the Argentinian director Alfredo Arias. In 1992, I helped Alfredo to write a musical called Mortadela, which became a huge success and had a long run of three or four years. Consequently, Alfredo asked me to write other plays for him, and up to now we have collaborated on about a dozen theater productions, most of them musicals. Alfredo also directed my La Dame aux Camélias, with Isabelle Adjani as Marguerite Gautier, performed at Théâtre Marigny in Paris during the season 2000–2001. (Recently it was staged in French at the Arclight Theatre in Manhattan with another team.) I also wrote several plays for other directors—a Polish one in Slovenia, for instance.

My collaboration with Claudia Cardinale is also very important to me. It started from my translation from Venetian into French of a famous, anonymous classical play La Venexiana, in which she performed at Théâtre du Rond-Point in Paris in May 2000 and then toured France with it the next year. This was her debut on stage, a big moment in her career. She spoke a lot to me about her beginnings in film. Since then, we became close friends. Last March, we read on stage at the Paris Cinémathèque fragments of her conversation with Moravia, who interviewed her when she was 23. I played the part of the writer. It was a moving experience for me, and for her as well.

Theater has been very important for me, also because writing is such a solitary experience. Working with and for actors gives me a strong feeling of communal experience. I like the smell of the stage, as well as the anguish of backstage and rehearsal. It is unforgettable.

Rail: You have mentioned Moravia several times in this conversation. Your last book, published a few months ago, is his biography. What motivated you to write about him?

Ceccatty: There are four different reasons for it. The first one is that I simply admire Moravia as a writer and person. I had known him for 10 years before he died. I have translated his books for twenty years. I think I know his work very well. I admired and admire his intelligence, his honesty, his culture, his curiosity for other people and other cultures, his lack of prejudice, and, last but not least, his friendship with Pasolini. Because his lifestyle and love was “foreign” to me, I have gained the right distance to him, based on sympathy and no identification.

The second reason is that I always wanted to write a book about Italy. I had translated many Italian writers, reviewed many of their books, and often met them. I had written two books about Pasolini and one about Sibilla Aleramo, but those two were very special writers, self-absorbed and very close to my sensibility. I wanted to write about someone different from me, far from me, who had been a witness and a sharp observer of contemporary world in every aspect of life: cultural, political, geographic, and social. Moravia was a great writer who had an insight into all aspects of personal (love, family, art) and social (professional, cultural, political) relationships. He criticized family, hypocrisy, and lies. He was a great reader, a great traveler, and a great journalist. So I knew that, when I would write about his life, I would understand not only a specific man but, through him, a world in its time.

The third reason for my interest in Moravia has to do with my knowing many of his friends, his widow, his ex-wife (they were not officially married), and many writers who were close to him. I know Rome and its literary milieu well. So it was not too difficult for me to speak with key people who knew Moravia.

Finally, the fourth reason is that, at the current stage of my literary life, I have difficulties with writing another “private novel,” a new autobiographical story. It is more interesting to immerse myself in another writer’s world and mind. I continue to be “blocked” by the problem I had with my novel Un père. Therefore, it has been the right time to write a long book on someone else and “forget” (if only one could forget) my own life.

Moravia’s life is fascinating. Born in 1907 in a half-Jewish family in Rome, he suffered from bone tuberculosis as a child. He began publishing very young (he did not lose time in school!). He became a witness and a victim of the spread of fascism in the 1930s. He belonged to Italian history of the first part of the 20th century and beyond. Moravia’s relationship to history was very profound: he belonged to and shaped it. I always admired his freedom and the way he protected it. To our day, he remains the sole Italian writer who masterfully used fiction to express himself.