Story highlights

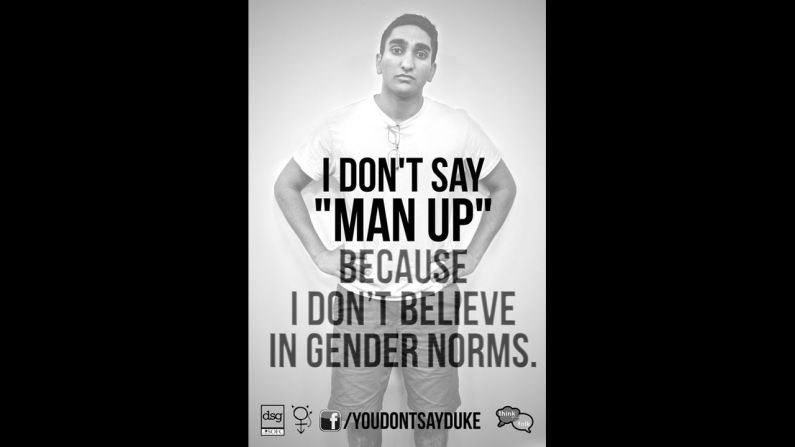

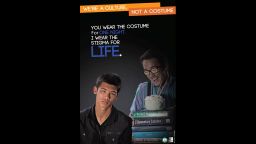

Duke students created a campaign to point out language that marginalizes others

The "You Don't Say?" campaign has taken off online

Instead of dehumanizing others, students say, use language to build each other up

This fall, two student organizations at Duke University met to discuss a simple idea: Put a spotlight on reasons people might take offense to phrases and slurs used in everyday conversation.

The result of that conversation – the “You Don’t Say?” campaign, a photo project that points out language that marginalizes sexual and gender minorities – has been sweeping across the Web and the Durham, North Carolina, campus.

It comes in the midst of several photo campaigns at colleges around the country. At Harvard, there was the “I, Too, Am Harvard” photo project that highlights the experience of its black students. In March at Georgetown, images of administrators in drag explored the issue of gender identity.

Duke sophomores Daniel Kort, Anuj Chhabra, Christie Lawrence, and Jay Sullivan co-founded the project. Kort is the president of the undergraduate LGBTQ group Blue Devils United, and Chhabra is the president of Think Before You Talk, a group aimed at bringing awareness to the implications of offensive language. Lawrence and Sullivan serve on Think Before You Talk’s executive board.

The students explained via e-mail why they got involved, and what they hope the photo campaign will accomplish. Their responses have been edited for clarity.

Anuj Chhabra on using the phrase ‘That’s so gay’:

I thought it was important to bring awareness to the implications that these words have because having used some of [these phrases] in high school, I quickly realized how differently other Duke students perceived me [when I commented], “That’s so gay.”

One of my friends in particular would constantly question me: “What do you mean by ‘That’s so gay?’”

I realized that using the word “gay” to describe a teacher who I didn’t like or an unfavorable event really didn’t make sense, and I began to change the habit.

Our intention was to use personal testaments to let people personally challenge themselves, as opposed to “banning” these words. Our desire to use the personal “I” stems from the fact that most people, after thinking about why it is so common in today’s society to equate something like “dumb” or “unfavorable” with “gay,” are quick to change their habits.

It is not necessarily homophobic or sexist people using such words and phrases, but largely just ordinary people.

Daniel Kort on why he participated:

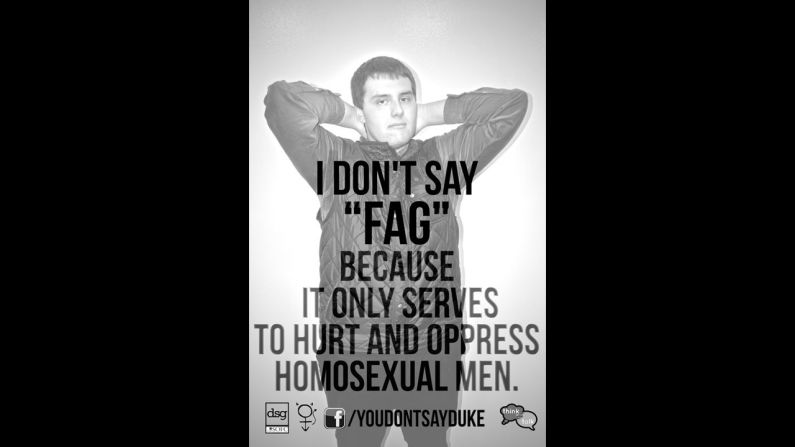

Throughout elementary and middle school, I was consistently bullied by my classmates because of characteristics that others deemed “gay.”

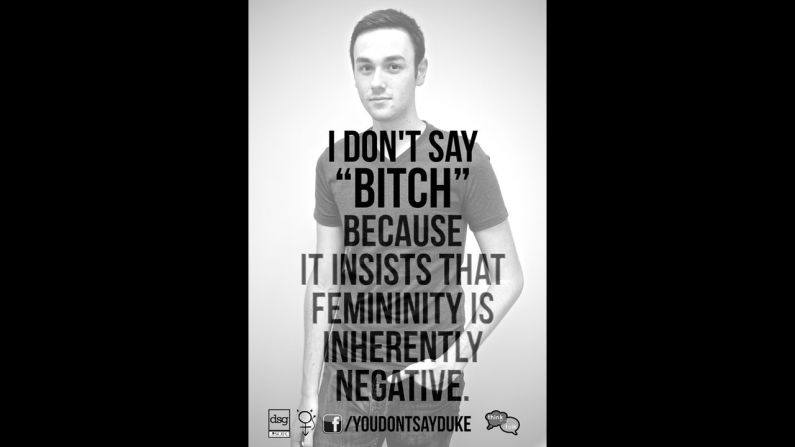

I was constantly called “fag” and “bitch.”

At times, it felt as if my entire class was against me, and I can recall only one instance that somebody stood up for me.

I would cry to my mom during the car ride home, and my schoolwork and motivation suffered.

With help from the school counselor, I was eventually able to stand up for myself and disregard my bullies.

In my first year [at Duke], I was called a “fag” by one of my hall mates in the first month of school. I was lucky to have my friends there to intervene, but I know that not all students are as fortunate.

I was motivated by the bystanders who were there for me that night, and this experience propelled my enthusiasm to work on the campaign.

Though I don’t have the same reaction nowadays in response to these words, I stand in solidarity with younger students who are marginalized by their classmates.

Christie Lawrence on how these terms impact her and others:

All of these phrases impact me, whether they directly address me or not. I think it is important to try to be as good of a person as you can, and through conversations with my friends, I have grown to recognize the hurt these words can inflict.

Even if I am not gay, I know that calling someone a “fag” or qualifying an expression of admiration with “no homo” attaches hurtful connotations to words that are directly connected to a certain identity.

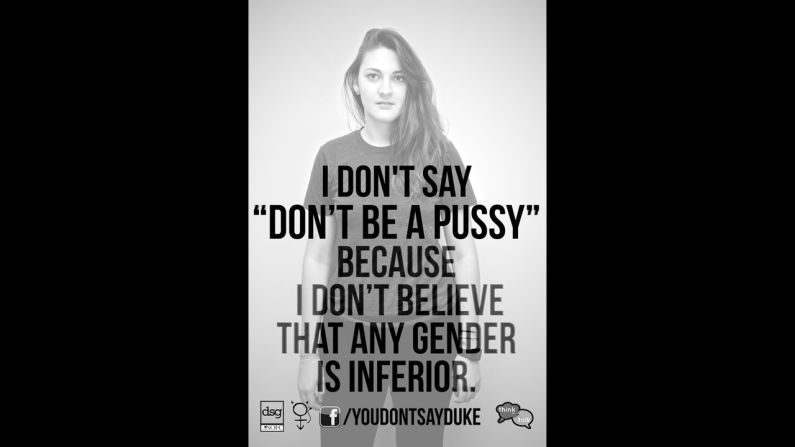

Telling me to “man up” or not be a “pussy” tells me that you believe women are weaker, more emotional and lesser than a man. It tells me that you think a certain way to act is the right way and anything that does not fall under the umbrella of “acceptable” behavior or emotions is something to be put down. This attitude, that there is a correct way to have courage, be successful, or achieve happiness, is something that I believe hurts everyone in our society, including myself.

This campaign is not an attempt to ban words or invalidate someone’s right to free speech, but instead is an attempt to show how these words are hurtful for many. One comment on an article I read about our campaign explained it very nicely: You have the right to say these offensive phrases, but we also have the right to tell you why we think these phrases are hurtful.

Jay Sullivan on how language reflects values:

I am a Christian. That is the lens I bring to all the work that I do in the community here at Duke, in the local Durham community, and in my daily life.

When I was in high school, I was the leader of the my school’s small Christian Fellowship. I went to a private co-ed prep school in New Haven, Connecticut, called Hopkins School, and I distinctly remember during my junior year during the day of silence I was wearing an ally sticker in support of my friends who were silent. In class that day, an older friend came up to me and said, ‘“Look, Jay, I respect you but you need to take that ally sticker off man. You’re condoning their sinful actions. You can’t support them and be the leader of a Christian organization.”

I was quite taken aback, and after a short dialogue I took off the sticker to avoid any further conflict. That experience bothered me for a while, that I didn’t take a stand to tell him, “People are people and they deserve the same rights and freedom to live the way they want that you have, as well. God loves everyone regardless of any part of their identity that you may have deemed sinful or unworthy.”

This campaign is not about language; it is about what this language represents.

The way we talk is a reflection of our beliefs and perceptions of the world and it is vital, at least for me, to examine whether what I say is in line with my values and how I view the world.