Mahjong, the centuries-old Chinese tile game, became embroiled in controversy last week over a debate about cultural appropriation.

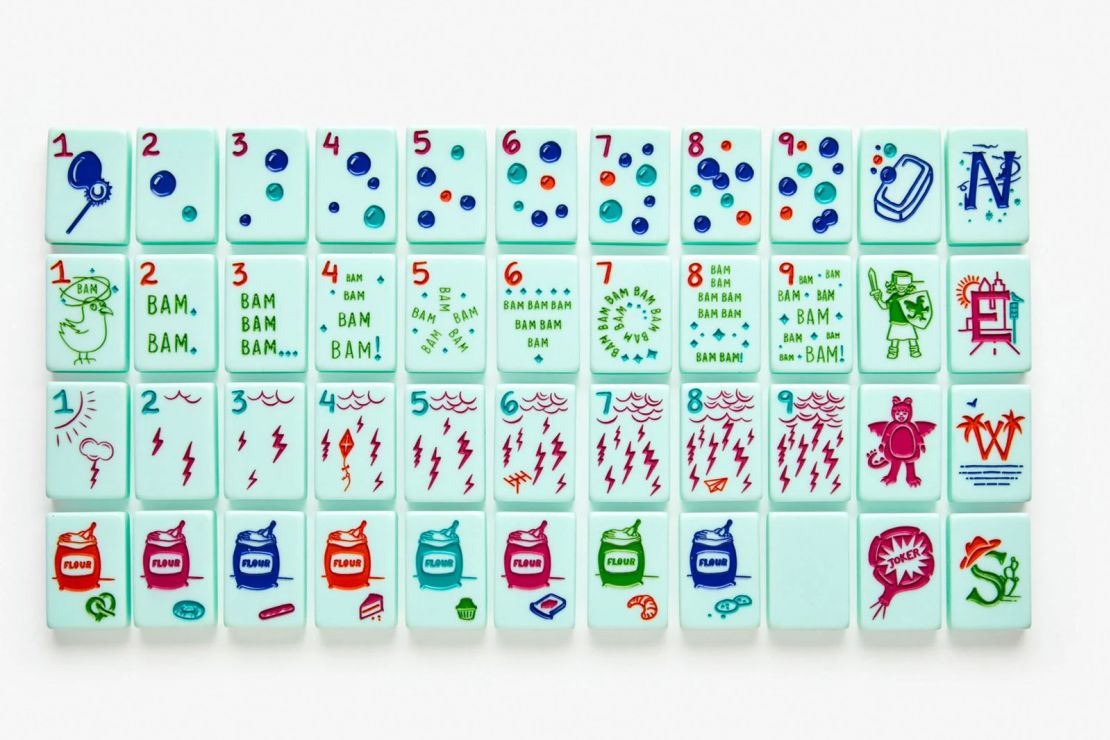

Criticism erupted online over The Mahjong Line, a Dallas-based company founded by three White women, that sells brightly colored tiles with reinvented symbols – bags of flour representing the traditional flower tile, for instance, and the written word “bam” representing the bamboo tile.

The artwork featured on traditional tiles, “while beautiful, was all the same,” the company said on its website, adding that “nothing came close to mirroring (the founder’s) style and personality.” The new tiles offered a “respectful refresh” of American mahjong, which differs slightly from traditional Chinese mahjong in its rules and gameplay, the company said.

The website has since been changed to remove these phrases.

The tile sets were also marketed with different personality profiles – the “Cheeky Line,” for example, represented the type of “gal” who is “equally happy in LA or Austin. Loves a wild wallpaper, millennial pink and her many sneakers.”

Images of the tiles and screenshots from the company’s website were posted on Twitter last week, sparking an online controversy almost immediately. Social media users, including those from the Asian American community, accused the founders of cultural appropriation, disrespectful language and ignorance toward the game’s cultural significance (while profiting from it – each set costs $325 or $425).

“Please put the Chinese characters BACK onto the Chinese game. Don’t change my history and culture to make it more palatable to you,” tweeted Taiwanese American Rep. Grace Meng, New York’s first Asian American member of Congress.

By Wednesday, the company had apologized and updated its site. “While our intent is to inspire and engage with a new generation of American mahjong players, we recognize our failure to pay proper homage to the game’s Chinese heritage,” it said in a statement.

But the company has not stopped selling its games.

“We stand by our products and are proud to be one of the many different companies offering a wide range of tiles and accessories for the game of American mahjong,” said co-founder Kate LaGere in a statement to CNN. “That being said, we take full responsibility that in our quest to introduce new tiles we unintentionally recreated an experience shared by many Asian Americans of cultural erasure and are working to correct this mistake.”

This is just the latest in a long string of similar incidents that have sparked outrage in recent years. The pattern is familiar now: Someone borrows or misrepresents a piece of Asian culture, becomes the target of online criticism, offers an apology and a promise to do better, and the Twittersphere moves on – until the next controversy.

But as each outrage comes and goes, the same question re-emerges, from both outside and within the Asian American community: Where do you draw the line between appreciation and appropriation?

Ongoing debate

“When cultures are inspired by another culture, that’s one thing,” said Nancy Wang Yuen, a sociologist and author who writes about race and representation, in a phone interview. “But if they claim to improve upon and disrespect the original culture, or if there’s an air of superiority over the original content, then that becomes appropriation.”

Part of the offense comes when those doing the appropriating make “a claim of authenticity … when they’re not actually using any … Asian talent,” said Yuen. For instance, restaurants that claim to serve authentic Chinese food without using any Chinese consultants or staff – or, in this case, a mahjong company that is headed by White founders.

The past few years have seen countless controversies resulting from perceived appropriation, particularly in the fashion world. In one famous incident in 2018, a White high school student wore a traditional Chinese qipao (or a cheongsam depending on dialect) dress to a prom in Utah. The backlash was swift, with Chinese Americans tweeting in response, “My culture is not your prom dress.”

Celebrities have been called out too: Kim Kardashian West’s lingerie brand, originally named Kimono, was heavily criticized when the star attempted to trademark a specific font version of the word, so much so that she renamed it in 2019. (Kimonos are a traditional Japanese garment that date back centuries.) Soon after, singer Kacey Musgraves was lambasted for taking revealing photos in a traditional Vietnamese ao dai dress.

But appropriation and its accompanying controversies take place in other spheres of life, from food and makeup to language and speech. And, Yuen said, it’s most harmful when there’s a power difference between the appropriators and the group they’re borrowing from – a dominant group “denigrating” the minority culture while profiting from it or misrepresenting it, as she put it.

In 2019, for instance, a New York restaurant sparked uproar and accusations of racism and cultural appropriation, after its White owner said it would serve “clean” Chinese food that wouldn’t make people feel “bloated and icky.” The restaurant closed just eight months after opening.

The “fox eye” beauty trend also went viral in 2020, with people trying to emulate the so-called “almond-shaped” eyes of celebrities like Kendall Jenner – an uncomfortable sting for Asian Americans who received racist taunts in the past for those same facial features.

Minority groups can commit appropriation, too – some Asian American entertainers, such as singer and actor Awkwafina, have faced criticism for, at times, speaking with a “blaccent” and appropriating African American Vernacular English.

Calling out offenders

Cultural appropriation itself is nothing new; it’s been happening for centuries. For instance, Dior has been referencing Chinese fashion since the mid-20th century. Even further back, Chinese motifs were commonly seen in 19th-century French and Italian fashion.

But, increasingly, people are calling it out – partly because of the ubiquity of social media, Yuen said.

“With the popularity of social media and the ease of having your voice heard even if you’re not famous – I think that allows for people to comment on and bring attention to practices that have been long standing … of appropriating non-Western cultures, as well as the native cultures,” she said.

Apart from providing a platform for people to voice their opposition, social media also allows the opinions of relatively anonymous characters – say, a teenager in Utah – to be seen and shared by mass audiences, she added. Problematic content that may previously have gone unnoticed can now spread like wildfire.

But online controversies often reflects a growing national conversation about race, racism and identity in the US. The country has experienced a cultural reckoning in the past decade, with people of color and minority groups pushing for greater representation, recognition and opportunity. The Asian American community has enjoyed a rise in visibility among the general public, with the emergence of pop culture successes like “Crazy Rich Asians” and “Fresh Off The Boat.” Younger activists and artists are increasingly vocal in sharing not just aspects of their culture, but also the ways they navigate mainstream society and the realities of racism and Asian stereotypes.

There is a “growing awareness of injustices, of all sorts – structural injustices, societal, as well as cultural in this case,” Yuen said, referring to the redesigned mahjong sets.

“I think the combination of the rise of social media (and) the rise of Asian American popular culture in the general consciousness, also allows for non-Asians to help to ally with Asian American communities,” she added.

“That then amplifies Asian American voices beyond the community, which is necessary because Asian Americans (account for about 5.6%) of the United States. So for something to go really viral, there also needs to be people who are interested in supporting and amplifying our causes and our issues.”

The flip side

This rise in activism and cultural sensitivity has been met with skepticism in some quarters.

Some have argued that the debate on appropriation stifles innovation and collaboration, pointing to popular fusion cuisines or pieces of art inspired by other cultures. Others have raised questions about cultural ownership and gatekeeping.

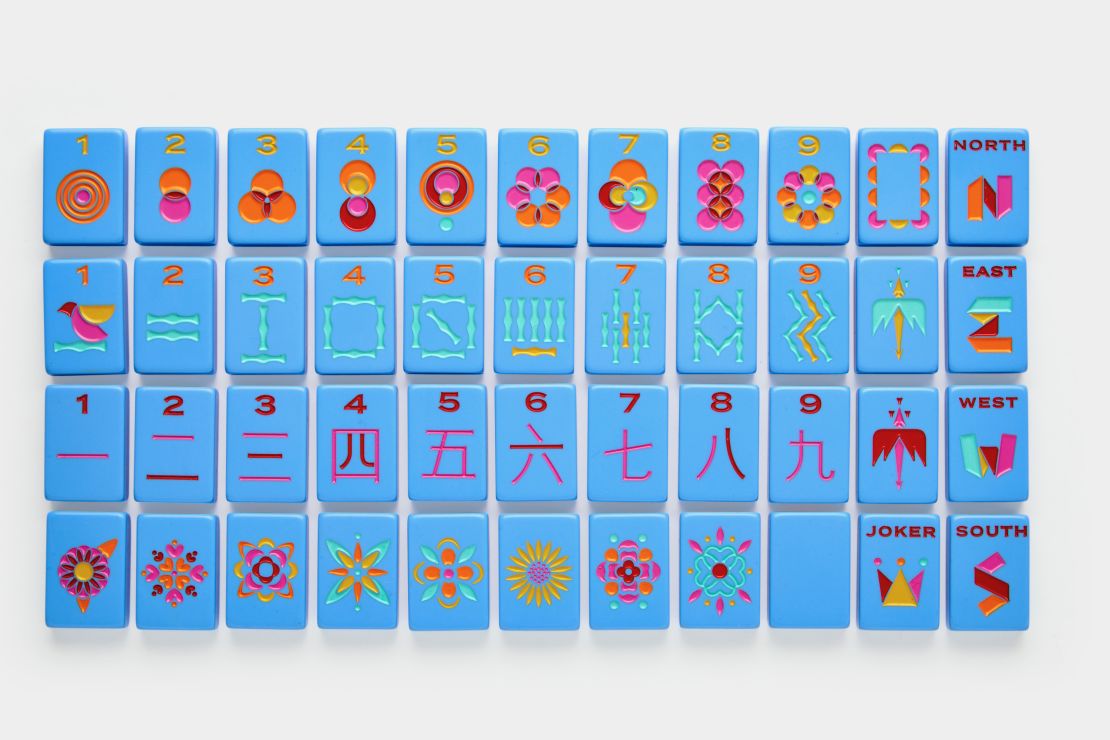

Mahjong, for instance, doesn’t have just one “correct” form; the game has evolved into different variations played in different communities. American mahjong, the variant that inspired The Mahjong Line, was introduced to the US in the 1920s. The rules were changed and the game became distinctly different from the traditional form played in China. Over the decades, it became culturally significant in different American communities, including among Jewish families following World War II.

“Mahjong has been changing ever since it first came on the scene (in China) in the mid-1800s,” said Gregg Swain, an American mahjong expert whose work informed the founders of The Mahjong Line when they launched the company in November 2020. “Versions of the game, and the tile set itself, have been altered to fit into different cultures and regions.”

Others have voiced concern that this heightened public awareness could compromise critical nuance, especially when each case depends so much on its individual context. Critics point out the danger of blind outrage becoming a knee-jerk reaction, with social media so easily escalating controversy.

Yuen offered another take to these criticisms: Think of it not as “cancel culture,” but “consequence culture.”

“I think people are tired of the history of cultural appropriation,” she said. “People are, for the first time, able to voice discontent … That’s how growth happens.”

“The problem is not when (activism) is taken too far,” she added – the problem is when offenders shut down the conversation because they feel attacked, instead of taking the step to recognize their privilege, educate themselves and engage with those minority communities, she said.

Besides, she said, most people who call out appropriation aren’t demanding that only Chinese people can play mahjong.

“A lot of people are saying that companies should donate to Chinatown causes, and causes that are under siege because of anti-Asian racism,” she said. “If you are going to engage with Chinese culture through mahjong, you need to understand the community’s needs. And rather than flippantly insult them, you need to engage with them, and bring them into your research and into dialogue.”

As for The Mahjong Line, the founders said they had been aware of the cultural sensitivity of the game, and tried (however unsuccessfully) to pay proper tribute. They researched “the evolution of the tiles over the history of the game for both Chinese and American mahjong,” as well as consulting with instructors, and seeking feedback from “a broad range of people” when creating the brand, LaGere said in her statement to CNN.

Still, she acknowledged they “failed to get perspectives from individuals more closely affiliated with the origins of the game. A grave mistake we take full ownership of.

“Moving forward, we will continue having conversations with experts closely tied to the game’s origins to ensure its rich history and cultural significance is properly represented in our promotion and description of the game,” she said. “This will be an ongoing process which will take some time as we continue to expand and roll out new policies in line with our goals to further (educate) ourselves as entrepreneurs in this space.”