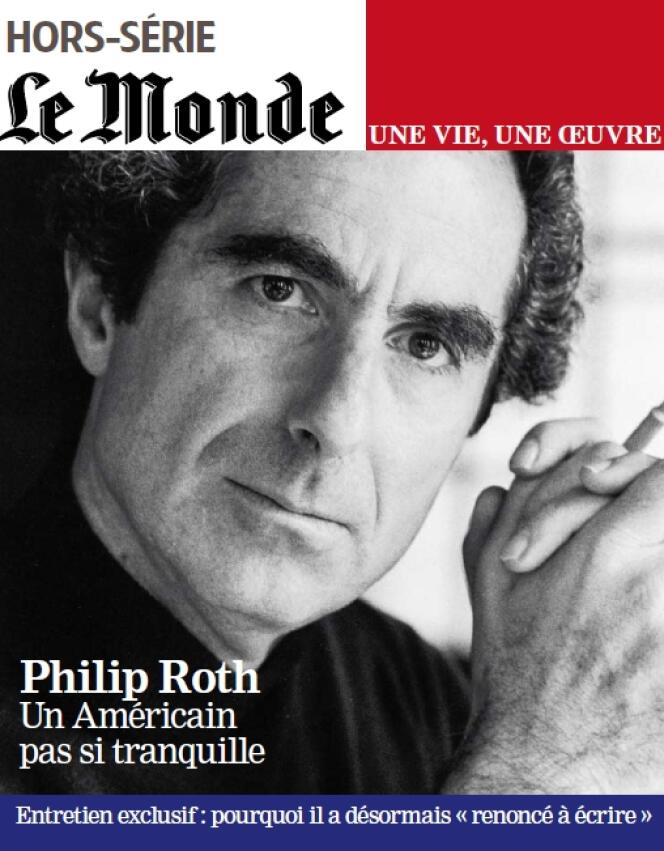

La version intégrale et en anglais de l'interview de Philip Roth par Josyane Savigneau pour le hors-série Philip Roth du Monde.

The long form transcript of an interview made in New York on January 12th by Josyane Savigneau for a special issue on Philip Roth by "Le Monde".

When did you decide to reread all your books?

Well, to begin, for the last three years I have written no fiction. All I have written is archival material for my biographer. If I find a document, a pack of notes, a letter – and I have found hundreds – I have to explain to the biographer what the document signifies: what it's about, what were the circumstances by which it came about, who exactly are the people involved. That's the only kind of writing I've been doing. Forensic writing. And it's been a lot easier than writing fiction. I write just a single draft, so it's not at all like the endless rewriting of fiction and all the doubt that goes with it. That's how I've occupied myself, getting the documentation of my life in order to provide the biographer with his primary material. I don't want to write fiction anymore. A fifty year struggle is quite enough. I don't wish to be a slave any longer to the stringent exigencies of literature. I've overthrown my master and am free to breathe. Three years back, when I gave up writing, I decided to take all the free time I now had to reread the novelists whom I'd most loved as a young man – Dostoyevsky, Turgenev, Conrad, Faulkner, Hemingway, the stories of Chekhov…

Not Kafka?

I have read enough Kafka in my life. I saturated myself with Kafka in the 1970s, read it, studied it, taught it, and then read it all over again. After rereading my greats, I decided it was time to reread my own books.

You had never done it before?

Only intermittently, only in bits and pieces. I wanted to see if the effort had been worth it. I started at the end, with my last book, Nemesis, and then I proceeded to read backwards. I stopped reading just before Portnoy's Complaint. I had no interest in reading my first four books.

But Portnoy's Complaint is a major Novel...

In my first four books I was trying to find out the kind of writer that I was. Of course, I wasn't conscious then of what I was doing, but that is what I was up to. Kind of flailing about – try this, try that, try the other thing… What was I looking for? Where is my strength? Where is my force? Where is my fluency? What best sustains my verbal energy?... Now, we had a great boxing champion in America when I was a kid. Black heavyweight champion named Joe Louis. Great fighter, maybe the greatest of the era, born in Detroit, hardly educated, tough childhood, etc... He quit boxing undefeated. And when he quit and the reporters asked him about his career, Joe replied neatly, succinctly, with ten wise, wonderful words: “I did the best I could with what I had.”

So, you wanted to stop while you were still undefeated...

Oh, I've been defeated plenty. But I too did the best I could with what I had.

Going back to Portnoy. You already had problems with the Jewish community with Goodbye, Columbus…

Well, I certainly didn't think that Portnoy's Complaint was going to help things any.

Portnoy likes baseball, so do you. Do you still think that Europeans do not understand baseball?

Baseball has two main elements that grip the fan. Like many other sports, it has great subtlety and it has individual heroism. As an American child you're mesmerized by both. As a boy you play baseball all summer long, all day long and into the evening, so long as there is still light enough to be able to see the ball. Then as an adult, you watch it and follow it for the rest of your life, still like a child. Baseball is strictly an American, a Japanese, a Caribbean, and a Latin American passion.

When Portnoy complaints complains about his parents and their fear, his sister says, “if you had been in Europe, you might have died”. What was your experience of anti-Semitism when you were a child?

I'll tell you how I found out about anti-Semitism. I was born in March 1933. I was born the month Hitler came to power. He lived as a scourge until I was 12. Those first twelve years of my life, there was Hitler to remind everybody of anti-Semitism. He was the great murderous impresario of anti- Semitism. In addition, during the 1930s and 1940s, anti-Semitism flourished in America as well, in the forms of bias, discrimination, exclusion, and derision. The violence was minimal but the hatred was there and It wasn't invisible.

Did you see signs saying “No pets, no Jews”?

Yes, of course. “No Jews or Dogs Allowed.” There was individual Jew-hatred and there was institutionalized Jew-hatred.

Like Portnoy's parents, your parents had a harder experience of anti-Semitism...

We all experienced it. The intimate experience of it was minimized for me because I was raised in a hardworking lower middle-class Jewish community, our parents the offspring of immigrants keen on educating their young in American schools and preparing them for professions. No beards, no skullcaps, everyone speaking American English on the street and in the home, entirely Americanized, but very consciously Jews all the same. Newark was a city of working-class ethnic villages, that, in those days, were not wholly untouched by xenophobia: a Slavic village (Poles mainly), an Italian village (Neapolitans, Sicilians, and Calabrese mainly), a German village, an Irish Village (the Irish of course came to America, unlike the others, already speaking English), and the four smallest villages, a Jewish village, a Negro village, a Greek village, and the tiniest, a Chinese village. It was on the whole like living in a miniaturized, mildly simmering Europe, sans the French and the Spanish. And, in fact, in the 1950s, the Portuguese crossed the Atlantic and began moving into the city in great numbers, and after them the Brazilians.

In my own community, far from being conscious of anti-Semitism as a fact of daily life, I experienced the opposite: Jewish comfort, Jewish solidarity, Jewish warmth, Jewish gaiety, Jewish anxiety, Jewish craziness, Jewish self-consciousness, Jewish self-love, Jewish comedy, Jewish anger, the ingrained Jewish hostility to exogamy, the Jewish uneasiness around Gentiles, and the bone-deep Jewish hatred of anti-Semitism. Hatred of it and fear of it. It was not so much the anti-Semitism that I felt as it was the Jewish wound. The two most famous Americans of the 1920s and 30s were among our most vociferous and shameless American anti-Semites. There were plenty more among the eminent – including the father of President Kennedy, Joseph P. Kennedy, then a multi-millionaire businessman and American giant of his time – but the two most famous were Henry Ford and Charles Lindbergh.

Everybody in the world knew who Henry Ford was – they knew about him even in India, even in Africa: the inventor of the mass-produced automobile and the assembly line. Lindbergh was the world's greatest aviator, the hero par excellence of the modern age. Towering figures and both uncompromising anti-Semites American-style. Henry Ford published a newspaper in Michigan, where the Ford cars were manufactured, which was an openly, avowedly anti-Semitic newspaper the Dearborn Independent. All of this stuff is in The Plot Against America. It's all in there. Read it.

Did World War Two change everything?

Well, it didn't change people's feelings. They still didn't like Jews and found them, at the very least, to be distasteful. But during the war the law changed. And given enough time, law will change feelings. What happened was that with all the patriotic rhetoric of World War Two about equality and justice and the overthrowing of oppression, it was very hard to continue the old prewar ways of racial and religious discrimination. Of course when the change came it was grudging, but nonetheless it was change. President Roosevelt's Fair Employment Practices Commission implemented executive orders that forbade discrimination in employment. Later, Congress passed the Equal Opportunity Employment Act. Employers could no longer discriminate, as they had, against Jews, Catholics and Negroes – against anyone. If people didn't get a job because they were being discriminated against, legal action could be taken against corporate oppressors.

Slowly, grudgingly, this began change things. The big companies didn't want to be embroiled in legal battles and so, again grudgingly, they took to hiring and promoting minorities. Of course, really significant advancement for blacks wouldn't come for thirty or forty years after Roosevelt, and then only with a tremendous struggle, but at last the white WASP hegemony had been made to yield, forced by the government to admit the nature of the society that was ours. The destruction of colonial tyranny in a savage war is the great American moral triumph of the 18th century. The destruction of institutionalized nationwide discrimination, against massive bigotry and entrenched economic resistance, is among the greatest American moral triumphs of the 20th. People can still hate whomever they want to hate – and life being life, plenty do – but those who are hated can now get ahead without the disgraceful old impediments.

118

Let's talk about a great book, Operation Shylock. How did it feel to create a double called Philip Roth, and play with your identity?

Well, I'm not the first one to be intrigued by the story of a double. There is Dostoyevsky's long story, The Double. There is Conrad's Secret Sharer, Stevenson's Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and more. But my idea was to make the man who has the double something other than a character in a book. I identified him as myself. The character who comes upon a living double is me. I thought that doing so might enliven my imagination and I think that it did. In this book where I and someone else appear under my real name as yoked characters, I propose many sides to “my” character that are not mine, many motives for actions that are not mine, and many bizarre encounters that never occurred where I sometimes behave outrageously but in which I never actually had the opportunity to perform.

I also propose many more fabricated characters, chaotic happenings, and unforeseeable adventures in the book, the adventure of greatest consequence – that I've already alluded to – being the one in which I am beset in Jerusalem by an audacious doppelganger bearing my name and become perilously entangled with this identical physical replica of myself, whose perversity, madness and strength seem boundless, and with his girlfriend, a beautiful oncology nurse who is a member of Anti-Semites Anonymous, a twelve-step rehab group for recovering anti-Semites founded in America not by me but by the spooky other Philip Roth. My hero, not only the other Philip Roth but the real Philip Roth, is an actor in an implausible plot, or perhaps I should call it a gigantic wrestling match. I very much like the screwiness of this book.

Did you also like Sabbath's Theater when you reread it?

I did. It's death-haunted – there is Mickey Sabbath's great grief about the death of others and a great gaiety about his own. There is leaping with delight, there is also leaping with despair. Much laughter, much grief. Yes, it's a favorite, too. Maybe my very favorite.

You say you wrote several novels about fear, including The Plot against America and Nemesis. Why?

Why don't you ask Kafka that question?

If you had children you would have advised them not to be writers. But, yourself, you decided to be a writer...

When you decide “to be a writer”, you don't have the faintest idea of what the work is like. When you begin, you write spontaneously out of your limited experience of both the unwritten world and the written world. You're full of naïve exuberance. “I am a writer!” Rather like the excitement of “I have a lover!” But working at it nearly every day for fifty years – whether it is being the writer or being the lover – turns out to be an extremely taxing job and hardly the pleasantest of human activities.

Were you happy?

Of course. I was of a generation of American writers born in the 1930s, post-Hemingway – and intoxicated by the artistic zealotry of Gustave Flaubert, by the moral depths of Joseph Conrad, by the compositional majesty of Henry James – who believed they were embarking on a holy vocation. The great writers were saints of the imagination. I wanted to be a saint too.

Usually, when writers stop writing, they do not tell…

I guess they don't want it to get around that they've stopped. They don't want people to think that they've lost their magic. I really didn't go trumpeting the news about either. A young woman was here to interview me for a French magazine, Les Inrockuptibles, and near the end of the interview she asked, “What are you working on?” And I answered, “I'm not working on anything.” And she said, “Why not?” and I said “I think it's over. I think I'm finished.” That was it. I didn't intend to be making an announcement designed to produce a frenzy. I was just candidly answering a straight question put to me by a good reporter. Many months later, some eager journalist in America must have idly picked up an old copy of Les Inrockuptibles while waiting for a haircut in a barber shop and rushed it into print, the French translated by Google into comically inaccurate English.

You didn't anticipate that your decision was going to be commented on?

No.

Did you only say you stopped writing fiction?

Well, I certainly haven't written any fiction. As I told you earlier, I'm writing pages and pages of commentary for my biographer, but that's not writing fiction. It can't be. There's no misery in it.

I read somewhere that you were writing a short story with the 8-year-old daughter of one of your ex-girlfriends. Is it true?

Yes. Her name is Amelia. We've written several longish stories together, in tandem, by e-mail. She writes a paragraph, I write a paragraph, back and forth like that, raising the imaginary stakes as we go along. We're at work on a story now about two dogs who become scientists. The premise was Amelia's. She has an imagination like Ovid's. But this isn't me writing fiction, obviously. This is just my having fun with a clever and wonderful little girl whom I adore.

So, after rereading your books, you said: I have done the job, I can stop publishing now. It is okay...

I didn't say it's okay or it's not okay. I didn't have or need a rationale. I didn't want to do it any longer, so I stopped doing it. That's the whole story.

Was it a way to tell people: “You didn't really read me. Read me now!”?

Not at all. I just didn't want to do the job anymore, such as ever again falling in love, other than in a grandfatherly way.

You do not think the art of the novel is disappearing, but you think readers are disappearing. What do you mean? People think they read but they don't?

I mean the numbers of readers is shrinking, just like the polar ice-cap. The number of serious readers.

People still buy books, but do they really read them?

A serious reader of fiction is an adult who reads, let's say, two or more hours a night, three or four nights a week, and by the end of two or three weeks he has read the book. A serious reader is not someone who reads for half an hour at a time and then picks the book up again on the beach a week later. While reading, serious readers aren't distracted by anything else. They put the kids to bed, and then they read. They don't watch TV intermittently or stop off and on to shop on-line or to talk on the phone. There is, indisputably, a rapidly diminishing number of serious readers, certainly in America. Of course, the cause is something more than just the multitudinous distractions of contemporary life. One must acknowledge the triumph the screen. Reading, whether serious or frivolous, doesn't stand a chance against the screen: first, the movie screen, then the television screen, now the proliferating computer screen, one in your pocket, one on your desk, one in your hand, and soon one imbedded between your eyes.

Why can't serious reading compete? Because the gratifications of the screen are far more immediate, graspable, gigantically gripping. Alas, the screen is not only fantastically useful, it's fun, and what beats fun? There was never a Golden Age of Serious Reading in America but I don't remember ever in my lifetime the situation being as sad for books – with all the steady focus and uninterrupted concentration they require – as it is today. And it will be worse tomorrow and even worse the day after. My prediction is that in thirty years, if not sooner, there will be just as many people reading serious fiction in America as now read Latin poetry. A percentage do. But the number of people who find in literature a highly desirable source of sustaining pleasure and mental stimulation is sadly diminished.

For you, to be a writer means a lot of frustration. Can it also be a pleasure?

Yes. It's a pleasure for about a week and a half. When you finish a novel, you feel triumphant, until ten days later, that is, when you have to begin thinking about the undoability of the next novel.

In an interview for Le Monde in 2004, you said “When I start a book I am always a beginner”. Always?

Always. Always. You can say one of the reasons that I've quit is that after fifty years I was still an amateur – a clumsy amateur lacking confidence and wholly befuddled for months and months at the beginning of every new book. Now, luckily, I remain an amateur only at the rest of life.

Didn't you gain any confidence, little by little?

Not at the start of a book. It's a rare writer who is confident at the outset. You are just the opposite – you are doubt-ridden, steeped in uncertainty and doubt. Henry James, the great powerhouse of American fiction, the novelist's novelist – our Proust – put it perfectly while speaking, in a story of his, of the novelist's vocation. “We work in the dark – we do what we can – we give what we have. Our doubt is our passion and our passion is our task. The rest is the madness of art.”

Why did you appoint a biographer instead of writing your memoirs?

I didn't appoint a biographer. Blake Bailey, arguably the best literary biographer in America now, wrote me a letter introducing himself. He has written three excellent biographies, the best, to my mind, a brilliant biography of the late John Cheever, a novelist both searing and comic, a master short-story writer, a magical stylist, a genius of an American chronicler – if such a creature can even be imagined, a kind of lightheartedly grave, wholly American, eroticized Bruno Schulz. Blake Bailey and I corresponded and then he came to my home from Virginia, where he lives, and we talked together in my living room for two whole afternoons. I asked him a lot of questions. He claimed later that I had “grilled” him, and maybe I did. I watched him too, of course, to see what kind of man he was. He struck me as formidable in every way and so at the end of the second afternoon, with my heart in my throat, I said, “Go ahead. Do it.”

So, you work for him?

I work for him. I'm his employee. I do his spadework – unpaid.

How did you react to this sentence Charles McGrath wrote in The New York Times, “To his friends, the notion of Mr. Roth not writing is like Mr. Roth not breathing”?

It's kindly meant but it's romanticism. I'll be fine without writing. Maybe even happier. To tell you the truth, I'm happier already.

Read the short version of this interview in French : "Philip Roth : “Je ne veux plus être esclave des exigences de la littérature”"

(Copyright Philip Roth)

Voir les contributions

Réutiliser ce contenu