Relaxing near the entrance to a blood-stained alley off Cairo's central Tahrir Square, prominent engineer and political activist Mamdouh Hamza, 63, credits the Muslim Brotherhood with saving the day. "We needed them," he says. "They were very important to the resistance." A short distance down the alley, amid a warren of shuttered shops, is the makeshift hospital that treated the hundreds of anti-regime protesters who were bludgeoned, stabbed, shot, burned by Molotov cocktails, or hit by flying rocks during last week's pitched battle against President Hosni Mubarak's men. But the protesters managed to hold their ground—thanks to the Brotherhood's reinforcements, Hamza says, scanning the crowd in the square. "Half the people here, or maybe 40 percent, are Muslim Brotherhood," he says. "They were a very important factor."

The big question now is this: how much more important a factor will they become? The Brotherhood's hardline Islamist roots frighten a lot of people, both outside Egypt and in. Addressing Israel's Knesset last week, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu invoked the specter of Iran's 1979 Islamic Revolution, which brought the ayatollahs to power and transformed a staunch ally of Israel into one of its most implacable and dangerous enemies. Members of the U.S. Congress expressed similar fears. And so, of course, did Mubarak, who has presented himself as Egypt's last line of defense against a radical Islamist deluge ever since the October 1981 assassination of his predecessor, Anwar Sadat, by followers of a Muslim Brotherhood splinter group. He told ABC's Christiane Amanpour last week that although he's fed up with ruling, he can't abandon his post now or "chaos" would come.

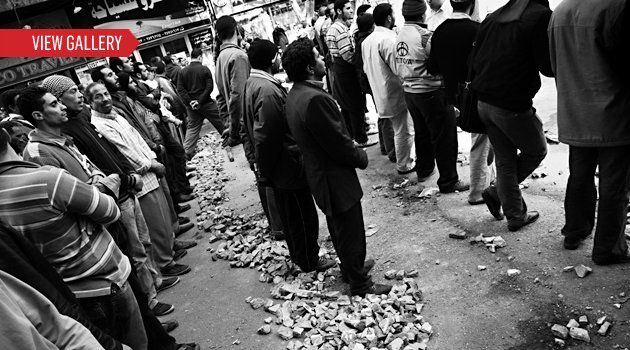

The nasty truth is that chaos has already arrived. In and around Tahrir Square, Mubarak's men charged on horseback and camelback into the peaceful throng of demonstrators, showered them with stones, and surged into their ranks with clubs and knives. The supposedly neutral Egyptian Army, mounted on U.S.-supplied M1A1 Abrams main battle tanks, sat back and let the pro-regime thugs carry out their dirty work. By the time the fighting stopped, the Brotherhood had won more popular support than ever, having earned the proudest epithets in the lexicon of Arab and Muslim politics: "resistance" and "martyrs." "The Egyptian administration is making the Brotherhood the face of the opposition," says scholar Scott Atran, author of Talking to the Enemy: Faith, Brotherhood, and the (Un)Making of Terrorists. And yet Atran argues that the group makes up only a small fraction of Egypt's populace, with no more than 100,000 or so followers in a nation of more than 80 million.

The Brotherhood, tellingly, had no part in hatching the protests. On the contrary, the group was caught at least as unprepared as the government. The actual instigators were a band of young techies who used their mass-communication skills to mobilize thousands of people from almost every stratum of Egyptian society in an uprising against Mubarak's reign—with the notable exception of the Brotherhood, which declined to join the first massive but peaceful demonstrations on Jan. 25. The group did participate in subsequent nationwide rallies, however, and it's impossible to say whether it had any involvement in the violence that marred some of those protests, such as the burning of Mubarak's party's Cairo headquarters on the night of Jan. 28. The president finally gave ground on Feb. 1 with an announcement that he would not run for reelection, but there was no doubt after that who was instigating violence. Mubarak's supporters and security apparatus went on the attack against protesters, journalists, and randomly selected foreigners.

Mubarak's evident strategy is like that of a gangster's protection racket, striking fear into the same society he claims to defend. Even so, the 82-year-old president can't hope to play this game much longer. Age and failing health will claim him even if the Army (under considerable U.S. pressure to resolve the crisis) chooses not to oust him. And through it all, it is the Brotherhood that will endure. "They are the best-organized group," says Atran. "They have been around forever. They are able to stay the course. They are not going to fold." The group was founded in 1928 by Hassan al-Banna, a firebrand who preached Muslim ideals but modeled his organization on other ideological movements of his era. "They were founded as paramilitary cells, on fascist and communist models, and that is how they survived," says Atran. "They were able to disperse when the power against them was strong, and then to unite very fast when power was weak."

The Brothers needed any survival skills they could muster. The group was ruthlessly suppressed by Sadat's predecessor, Gamal Abdel Nasser, in the 1950s and 1960s, only to enjoy a comeback as a political force in the 1970s. After Nasser's death in 1970, Sadat tried to make peace with the Brotherhood: in the depths of the Cold War, it looked like a potential counterbalance to communist-influenced parties that were seeking power across much of the Muslim world. The rapprochement ended in 1977, when the group joined in nationwide bread riots, and Sadat tried again to crush it. Meanwhile, the Israelis were cultivating the Muslim Brotherhood in Gaza, in an ill-conceived attempt to undermine leftist Palestinian groups. That branch of the Brotherhood later took a new name: Hamas.

The Brotherhood has spawned many sinister splinter organizations. Some are now its sworn enemies. Al Qaeda's second in command, Ayman al-Zawahiri, began his career as a disciple of a Brotherhood philosopher named Sayyid Qutb. But Qutb was only a marginal figure in the Brotherhood, and, as Atran notes, Zawahiri has spent "his entire active political life vilifying the Brotherhood as 'false Muslims,' cowards, and allies of Crusaders and Jews because of [the group's] willingness to peacefully participate in Egyptian politics, and for showing sympathy to Christians and Shiites who have been bombed and killed in Egypt, Iraq, and elsewhere."

The Saudis, who are often accused of fomenting radical Islam, nevertheless regard the Brotherhood with deep suspicion. NEWSWEEK has obtained an extensive dossier, compiled last year by Arab analysts with close ties to Saudi intelligence, that argues that a well-financed global Muslim Brotherhood network uses "moderate-seeming politicians to further its extremist agenda" as far away as Malaysia. Just a hint of Brotherhood involvement with the Tahrir protesters led Saudi King Abdullah to proclaim his support for Mubarak and denounce the Egyptian president's opponents as "infiltrators" who "spew out their hatred" while "inciting a malicious sedition."

Rashad Bayoumi, 76, the Brotherhood's deputy head in Egypt, denies any such covert aims. "What we want is for power to go back to the people so that everybody in society will be represented," he says. Still, he's well rehearsed in the Brotherhood's rather Jesuitical talking points. Asked if he would continue Egypt's diplomatic relations with Israel, Bayoumi says that the 1979 peace treaty between the countries was signed without the consent of the people, so it should be "renegotiated until people are satisfied with it." But talking to some prominent figures in the Brotherhood, one is left wondering who is leading whom. "I lived for years and years demanding that we stand up to Mubarak's authoritarian and oppressive regime," says prominent journalist and Brotherhood member Mohammed Abdel Qudous, 63, exhausted but elated. Other exhausted demonstrators seek him out to shake his hand or kiss him on top of the head. "Some people thought the Egyptian revolution would start from the poor working-class areas in Egypt or the labor leaders," he says. "But it was launched from the Facebook users." He shakes his head and looks at his hands, cut up from throwing rocks. He holds a folded Egyptian flag smeared with some of his blood. "For the first time, the young people who were born in the era of Hosni Mubarak came out. And many of them had never participated in a demonstration before. It was very natural, then, for me to leave everything and dedicate myself to the revolution until we win, Inshallah." God willing.

From the first, Islamists and jihadists outside Egypt have tried to claim a piece of the protesters' victories. Iran's Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei even talked of an "Islamic awakening." The Brotherhood quickly replied that the revolt against Mubarak was an "Egyptian people's revolution," not an Islamic one. And when the protesters got room to breathe, that's just what it has proved to be.

On Friday, the violence in Tahrir Square abated once again. Earlier in the week, under heavy pressure from the street, from Washington, and very probably from his own Army, Mubarak had finally named his first-ever vice president. Gen. Omar Suleiman, the longtime intelligence chief who got the job, went straight to work. Most of the thugs were sent home or kept at a distance by Army regulars. The Brotherhood's combatants nursed their wounds. The square filled once again with ordinary Egyptians—rich and poor, educated and uneducated, men and women and children.

After weeks of panic, Arab governments began taking a common-sense approach to self-preservation: yield a little to the opposition. Yemen's strongman, Ali Abdullah Saleh, allowed rallies to take place peacefully, and before they could gain momentum he announced he would not run for reelection in 2013 and would not try to have his son succeed him. Jordan's King Abdullah, faced with rising protests, named a new cabinet and promised popular reforms.

At least for the moment, the Brotherhood will remain an important player in the Arab world wherever it can participate in free and fair elections. Democracy is about organization, not the random will of the masses. The party that can get out the votes gets control of the government. But the Egyptians have known and watched the Brotherhood for a long time, and in an open, peaceful political system its mystique should soon disappear. As the Nobel Prize–winning Egyptian novelist Naguib Mahfouz wrote back in 1957, "The spread of learning is as liable to banish them as light is to discourage bats." When, finally, Arab governments come to understand that, the threat of the Muslim Brotherhood may well be over.

With Dan Ephron in Amman

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.