The Netherlands is well known for its clogs, tulips, and windmills. This small European country however is also known for the polder model, its approach to just about anything.

But 40 years ago this month, the country was the stage of a full-on war zone military operation, which ended in the longest train hijacking ever in the Netherlands.  On the morning of May 23 1977, nine armed Moluccans pulled the emergency brake on a rural train and took 52 passengers hostage. Four other Moluccans simultaneously took 105 children and five teachers hostage in a primary school in the same area in the north of the country.

On the morning of May 23 1977, nine armed Moluccans pulled the emergency brake on a rural train and took 52 passengers hostage. Four other Moluccans simultaneously took 105 children and five teachers hostage in a primary school in the same area in the north of the country.

The wreckage of the train carriage shootout at De Punt, where it was estimated that over 15,000 bullets were fired Source: Getty Images

The Dutch were furious. After all: these weren’t the first acts of terrorism this particular group had committed. There was the attack on a train in 1975 when 50 hostages were taken and an attack on the Indonesian Consulate in Amsterdam with 60 hostages of which 40 were children. Both incidents came to a bloody end.

Listen below: SBS Dutch Radio's Netherlands correspondent Marten de Jongh reports (in Dutch) about the transcripts of the liberation of the hostages after the train siege in 1977

LISTEN TO

http://audiomedia-sbs.akamaized.net/dutch_170607_696184.mp3

07:08

Who the Moluccans and what did they want?

In the 17th century the Dutch were fearsome seafarers, or rather, a ruthless bunch of pirates who sailed the Seven Seas looking for fortune and colonized Indonesia, renaming it the Dutch East Indies and turning it into an extremely lucrative natural resource of its spice trade, for the next three and a half centuries.

WWII however changed all that and the Indonesians demanded their country back.

The Dutch were not all that happy with this urge for independence and the KNIL (Koninklijk Nederlandsch Indisch Leger: the Royal Dutch-Indonesian Army) fought the locals in fierce battles.

The Moluccans as the 'Gurkhas' of the Dutch Indian Army

Some of this army consisted of a large group of professional soldiers from a particular part of the Indonesian archipelago, the South Maluku Islands. These Moluccan soldiers were like the Gurkha’s in the British Indian Army.

When the United Nations told the Dutch in 1949 to grant Indonesia independence, this group of soldiers naturally found themselves in a predicament.  Seen as traitors by the Indonesians, these soldiers and their families (12.000 in total) were exiled to the Netherlands with the promise that they would eventually get their own state, the Republic of South Maluku. In the meantime they formed a government in exile and called themselves RSM.

Seen as traitors by the Indonesians, these soldiers and their families (12.000 in total) were exiled to the Netherlands with the promise that they would eventually get their own state, the Republic of South Maluku. In the meantime they formed a government in exile and called themselves RSM.

Man from Sangliat Dol village in Yamdena island, Tanimbar archipelago, Maluku, Indonesia Source: Universal Images Group Editorial

Jobless and housed in former Nazi camps

On arrival in 1950/51 however, the soldiers were dismissed from the Dutch Army and everyone was housed in camps. Some of these camps were ex Nazi camps, often situated in isolated locations. Integration, education or participation in the labour market were never part of the Moluccan approach because the situation was seen as temporary: the plan was always for them to return to the Maluku Islands.

That never happened.

Instead they had to stay in the Netherlands in segregated communities where tension grew. The thought of having their own state became a distant dream.

READ MORE

Europedia podcast

Radicalization: kidnapping Queen Juliana

Just like in the Palestinian refugee camps all over the Middle East, tensions grew into radicalization when in August 1970 a group of second generation Moluccans attacked and occupied the Indonesian Embassy in The Netherlands, which lasted only overnight; the hijackers received mild sentences.  In March 1975 however, another group attempted to kidnap the Queen of the Netherlands, Juliana. Some members of that group were intercepted in a car full of fire arms intending to steal a truck and ram the gates of the Royal Palace to take the Queen. By December 1975 the radical elements in the RSM movement had regrouped and to draw attention to their case they hijacked their first train and at the same time they attacked the Indonesian Consulate.

In March 1975 however, another group attempted to kidnap the Queen of the Netherlands, Juliana. Some members of that group were intercepted in a car full of fire arms intending to steal a truck and ram the gates of the Royal Palace to take the Queen. By December 1975 the radical elements in the RSM movement had regrouped and to draw attention to their case they hijacked their first train and at the same time they attacked the Indonesian Consulate.

A Hijacker runs past the hijacked train with a South-Moluccan flag Source: Netherlands National Archive

But it was December, winter, and the conditions in the train were freezing so after 12 days the hijackers surrendered.

A hijacker seen climbing outside the train at De Punt Source: Netherlands National Archive

Their next act was better planned: on May 23 (late spring) 1977, they hijacked another train, as well as a primary school and held on for almost three weeks.  The demands were for the Dutch government to keep their promises about an independent state, to also sever all diplomatic ties with the Indonesian government and to free 21 Moluccan prisoners involved in the hostage actions in 1975. They then wanted an airplane to leave the country with all of the hijackers.

The demands were for the Dutch government to keep their promises about an independent state, to also sever all diplomatic ties with the Indonesian government and to free 21 Moluccan prisoners involved in the hostage actions in 1975. They then wanted an airplane to leave the country with all of the hijackers.

A hostage is seen leaving the train carriage during the 20 day siege Source: Netherlands National Archive

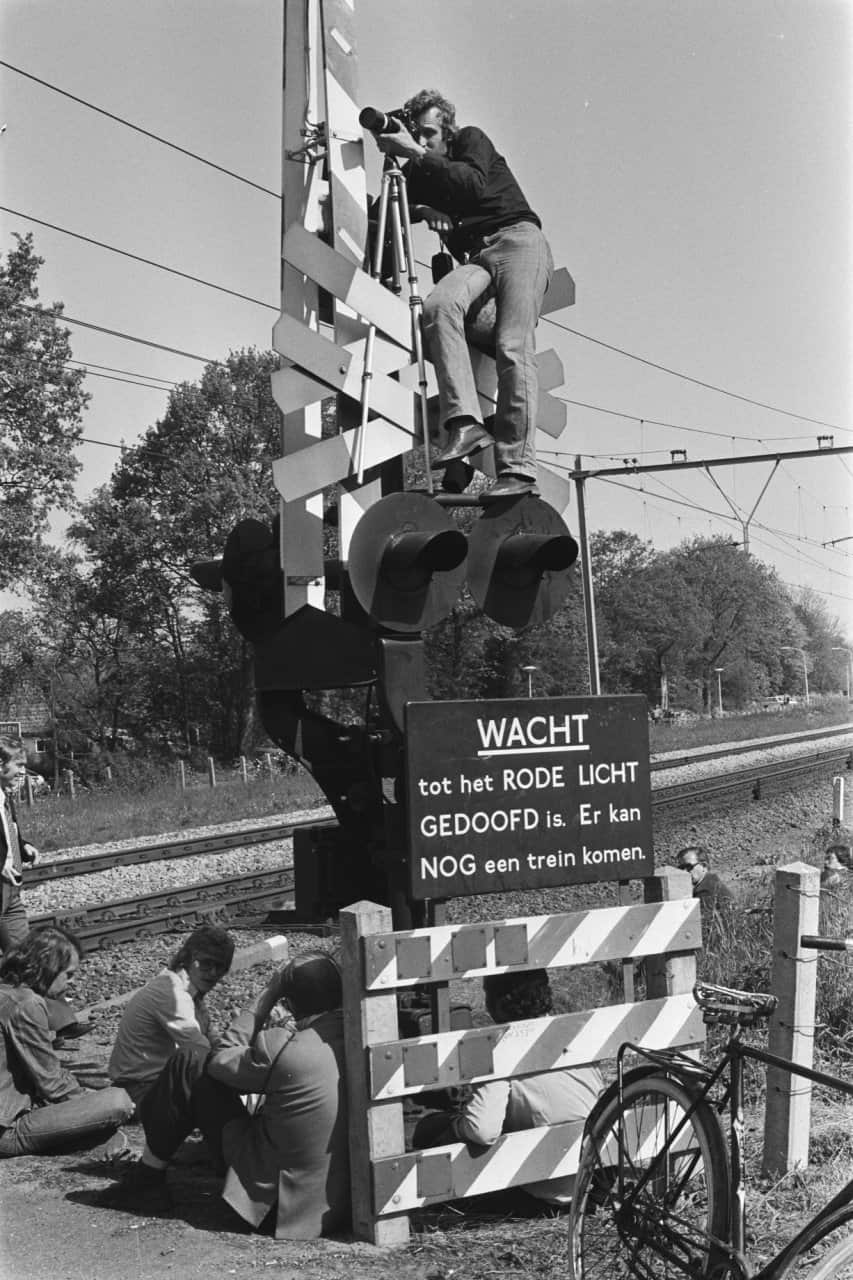

Crowds of press clamour to get a shot of the unfolding siege Source: Netherlands National Archive

Pizzas and pills, but no plane

The Dutch government wasn’t having any of that. They supplied both hijack locations with food and medication and secretly got ready for an ambush that would end both hostage situations in one hit.

In the meantime, the hijackers released all 105 children from the primary school with severe gastro. On June 11 1977 at 5am, six Starfighter jet planes distracted the train hijackers by low fly-over manoeuvres, while in a matter of minutes, soldiers from a special anti-terror unit fired 15,000 bullets at the train before the train was stormed.

On June 11 1977 at 5am, six Starfighter jet planes distracted the train hijackers by low fly-over manoeuvres, while in a matter of minutes, soldiers from a special anti-terror unit fired 15,000 bullets at the train before the train was stormed.

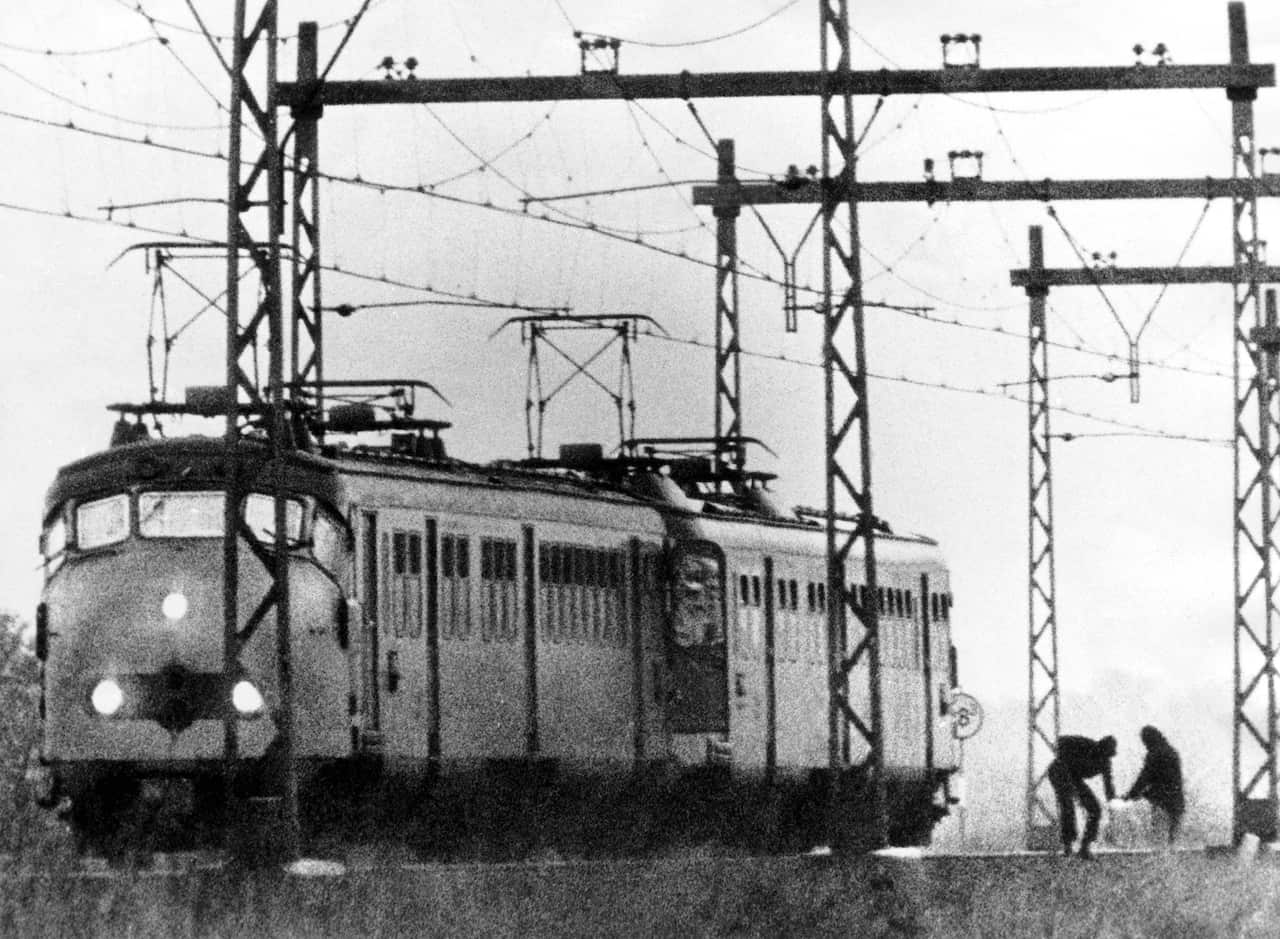

Two of the Moluccan terrorists leaving the hijacked train to collect supplies. Source: Getty Images

Two of the hostages lost their lives during this attack, as well as six of the hijackers.

An army tank driven into the school caused the hijackers there to surrender. It was a spectacular show of force. The remaining hijackers were arrested, referred to as prisoners of war, and the train with the thousands of bullet holes was driven all over the Netherlands in a display of victory, as if a war was won.

It was a spectacular show of force. The remaining hijackers were arrested, referred to as prisoners of war, and the train with the thousands of bullet holes was driven all over the Netherlands in a display of victory, as if a war was won.

Armed forces in place on the railway tracks during the 20 day siege Source: Netherlands National Archive

But was it a war and was it won and was the spectacular use of force justified?

Excessive force and executions

To this day the Moluccan community feels it has been wronged.

The community also feels that the intervention of the Dutch Army in 1977 was excessive, and that the hijackers were executed on the spot in spite of the fact that upon entering the train the hijackers were on the floor, wounded and unarmed.  And on the other side are all the surviving hostages of all these acts - people who have not reached their full potential in life because of PTSD, people who never travelled by train again, people who would have panic attacks seeing groups of completely innocent Moluccans hanging out in the street. People who have never had an apology.

And on the other side are all the surviving hostages of all these acts - people who have not reached their full potential in life because of PTSD, people who never travelled by train again, people who would have panic attacks seeing groups of completely innocent Moluccans hanging out in the street. People who have never had an apology.

A farmer pulls a tractor across a field in front of the hijacked train. Dutch sharpshooters are hidden beneath undergrowth surrounding the train Source: Getty Images

Court case against Dutch government for unlawful deaths hijackers

The Moluccan community finds the violent deaths of the hijackers a hard thing to get over. These young people were their children and they fought their battle against promises broken and injustices done.

In 2014 they demanded an in-depth investigation of the archives, which concluded that no execution had taken place, but that there were unarmed hijackers killed by special forces. In 2016, the community took the Dutch government to court for the unlawful deaths of their family members but their case was ultimately dismissed with too many versions about what happened in that train on that day. The real truth will probably never be known.

In 2016, the community took the Dutch government to court for the unlawful deaths of their family members but their case was ultimately dismissed with too many versions about what happened in that train on that day. The real truth will probably never be known.  On 11 June 2017 hundreds of members of the Moluccan community turned up at the graves of the hijackers to commemorate the 40 years since the military intervention whereby the hostages were released, but their Moluccan children died.

On 11 June 2017 hundreds of members of the Moluccan community turned up at the graves of the hijackers to commemorate the 40 years since the military intervention whereby the hostages were released, but their Moluccan children died.

Moluccans hold a Dutch and a Moluccas flag during commemorations for the six Moluccan hijackers of a train who died in 1977 in De Punt, in January 2014 Source: Getty Images

Chris Uktolseja, brother of Hansina Uktolseja, one of the killed highjackers speaks with lawyers at the Court of The Hague on February 1, 2017 Source: REMKO DE WAAL/AFP/Getty Images

Listen below: 'Questions Remain.' Speaking to SBS Dutch Radio (in Dutch) a former Dutch Marine confirms that they were given orders to kill in 1977, even if the Molucans who hijacked a train surrendered.

LISTEN TO

http://audiomedia-sbs.akamaized.net/dutch_161022_574408.mp3

06:42

Watch Great British Railway Journeys with Michael Portillo at 7:30pm, Fridays on SBS Australia, with multiple seasons streaming now at

[videocard video="949776963631"]

Related

Questions remain