It’s fade out for Hong Kong’s film industry as China moves into the spotlight

Hong Kong produced 400 films a year in the early 90s, but that number has dropped to around 60 today

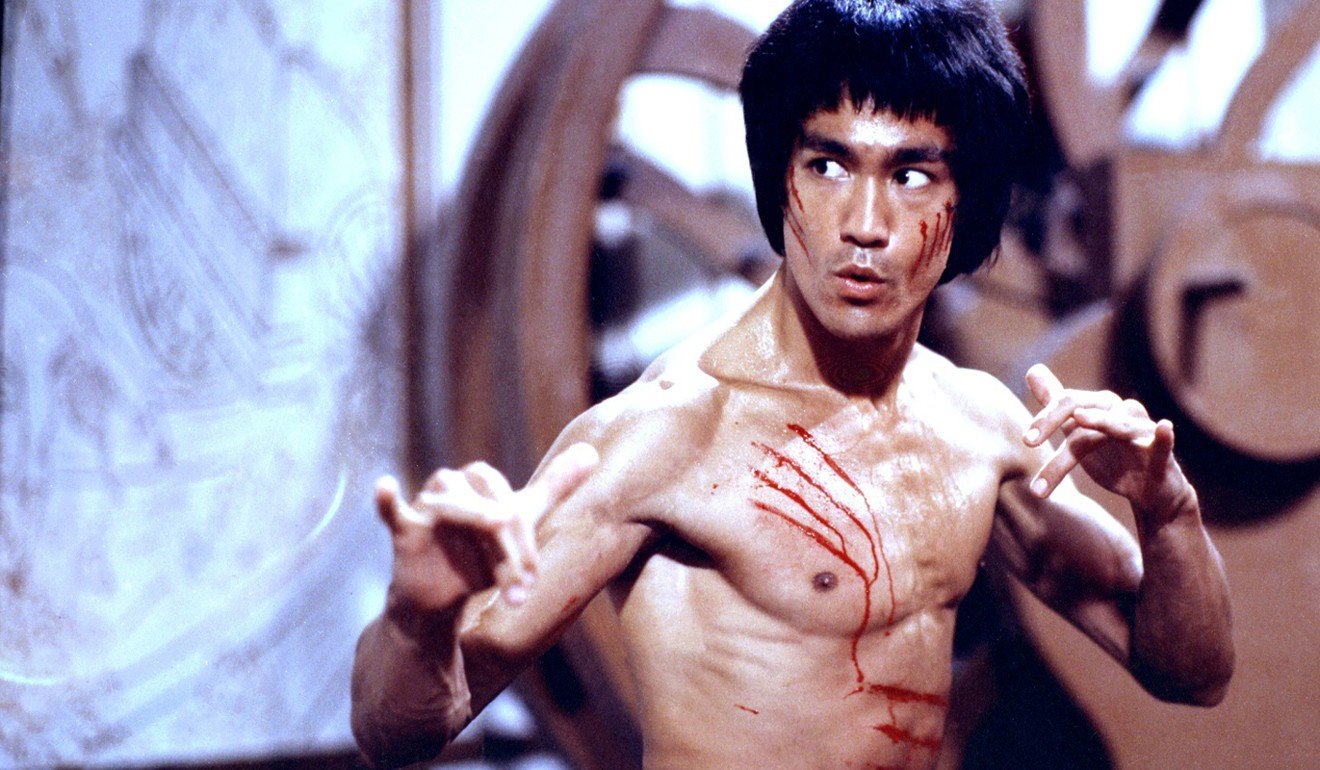

Still remember Bruce Lee’s cat calls, Wong Kar-wai’s impressionistic visuals in Chungking Express and Stephen Chow’s “mo-lei-tau” (nonsensical) comedies?

For almost three decades starting in the 1970s, there was nothing like it as Hong Kong’s film industry catapulted a large number of Asian A-listers to international stardom. But the golden days are long gone.

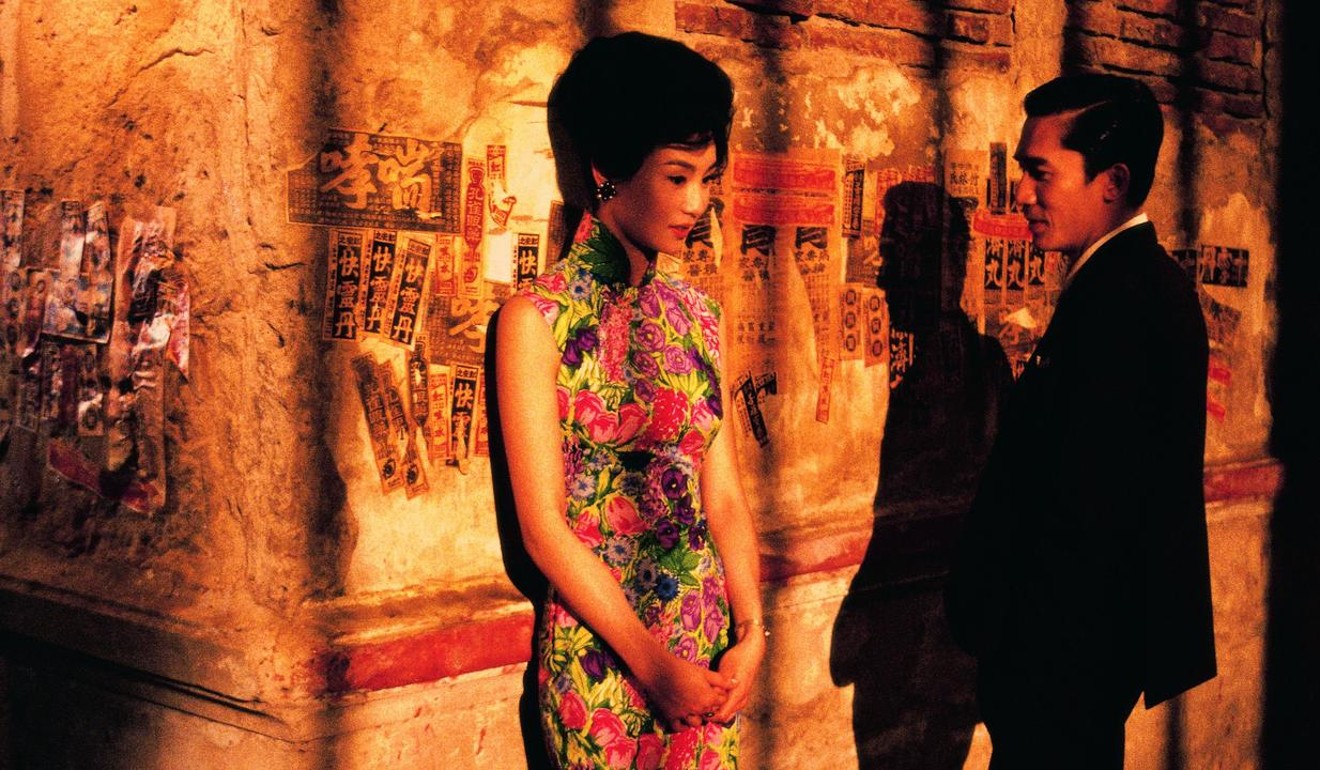

Hong Kong films have had little to no presence in recent years at Europe’s top film festivals – Berlin, Cannes and Venice – contrary to their heyday when the cast and crew of Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love and Happy Together strolled down red carpets while bagging top honours, among them Best Actor and Best Director trophies.

It is hard to nail down exactly why Hong Kong, once dubbed “Hollywood of the Far East”, lost its role as Asia’s movie capital starting in the 1990s. Many in the industry point to the brain drain where top talent headed north of the border to work on mainland Chinese productions, while others blamed it on the age gap between the veterans Wang and Chowand their millennial successors who are still struggling to gain a foothold.

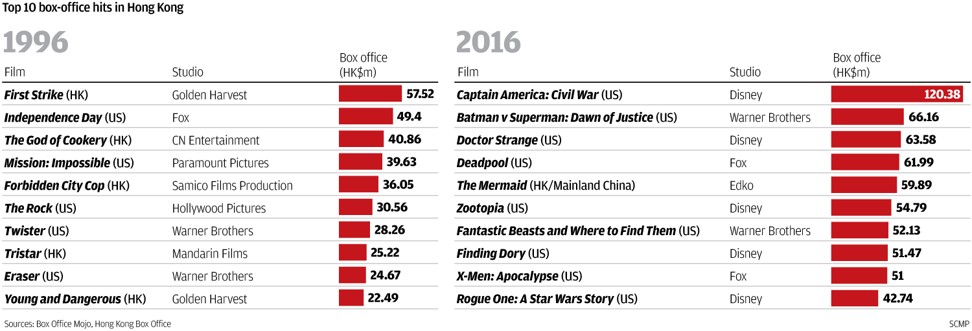

Hong Kong produced 400 films a year in the early 90s, but that number has dropped to around 60 today. In 1996, five of the 10 highest grossing movies in Hong Kong were home made. Fast forward two decades, and 2016 saw only one local top grossing film out of the top 10, The Mermaid, which was a mainland Chinese-Hong Kong co-production directed by Stephen Chow.

It is a similar story for Hong Kong’s major studios. Golden Harvest, the 47-year-old production house that nurtured the success of Bruce Lee in the 1970s and Jackie Chan in the 80s, lost traction in the late 1990s amid a double whammy of the Asian Financial Crisis and the rise of mainland rivals led by Huayi Brothers Media.

In subsequent years following Golden Harvest’s high point – the year Maggie Cheung won best actress award at the 1998 Hong Kong Film Awards for her role in The Soong Sisters, the number of its productions nosedived. Eventually, the iconic studio became a cinema operator and earlier this year sold its chain of mainland China theatres to Nan Hai Corp, owner of the Dadi Cinema chain.

“We are probably following the same pattern of our manufacturing industry. You reach a stage where you are looking at shooting films in China,” said Roger Garcia, executive director of the Hong Kong International Film Festival Society.

Just as low labour costs on the mainland drove Hong Kong’s factory owners to move their manufacturing plants across the border, in filmmaking a chronic dearth of tertiary education programmes in the city saw the local talent pool dry out.

“Beijing Film Academy, for instance, has educated generations of Chinese film personnel but in Hong Kong we are short of such institutions,” Pak-tong Cheuk, a film director and founder of the Academy of Film at Hong Kong Baptist University, wrote in a recent report on the film industry.

The slowdown in the growth of Hong Kong’s cinema market coincided with an astounding boom experienced by its mainland counterpart. Over the last two decades, China’s movie box offices has skyrocketed more than 40-fold to more than 45 billion yuan (US$6.6 billion) in 2016. Meantime, Hong Kong’s soaring rents have forced more than half of the city’s cinemas to shut down, official figures showed.

We are probably following the same pattern of our manufacturing industry. You reach a stage where you are looking at shooting films in China

“The biggest change is evidently the rise of the massive China film market,” said Albert Lee, chief executive of Emperor Motion Pictures.

As cinemas vanished from Hong Kong neighbourhoods, local audiences shifted their interest to Hollywood productions and away from the city’s traditional kung fu and triad films.

“In the 1990s, foreign audiences’ frenzy about Hong Kong productions cooled down,” said a 2016 research paper by the Legislative Council.

Confronted with a small domestic market, most of the major Hong Kong studios have embraced co-productions with their mainland counterparts.

Emperor has partnered with Huayi Brothers and Le Vision Pictures to produce blockbusters such as Personal Tailor and The Bullet Vanishes. The cast is usually a mix of mainland stars and familiar Hong Kong faces.

As mainland China continues to build up its pool of home grown talent, experts called on Hong Kong filmmakers to set their sights on lower budget films.

Over the past two years, home grown independent films such as Port of Call and Mad World – produced on budgets of US$5 million and US$258,000 respectively, have generated attention after scooping up prizes at the Golden Horse Awards and Hong Kong Film Awards.

Some of the world’s top filmmakers have already been lured to Hong Kong’s independent film scene. Andrew Hevia, a co-producer of best picture Oscar-winner Moonlight, is currently working with a local director to produce a low budget film in the city.

“I am a big advocate for communities making films about themselves,” Hevia said in an interview with the South China Morning Post in March.