Hong Kong villagers using solar energy to help power their homes - and show its potential as a source of electricity for city

Researchers say fitting solar panels to homes and buildings could produce 10 per cent of Hong Kong’s energy, but there’s no coherent policy for their use or incentives to install them

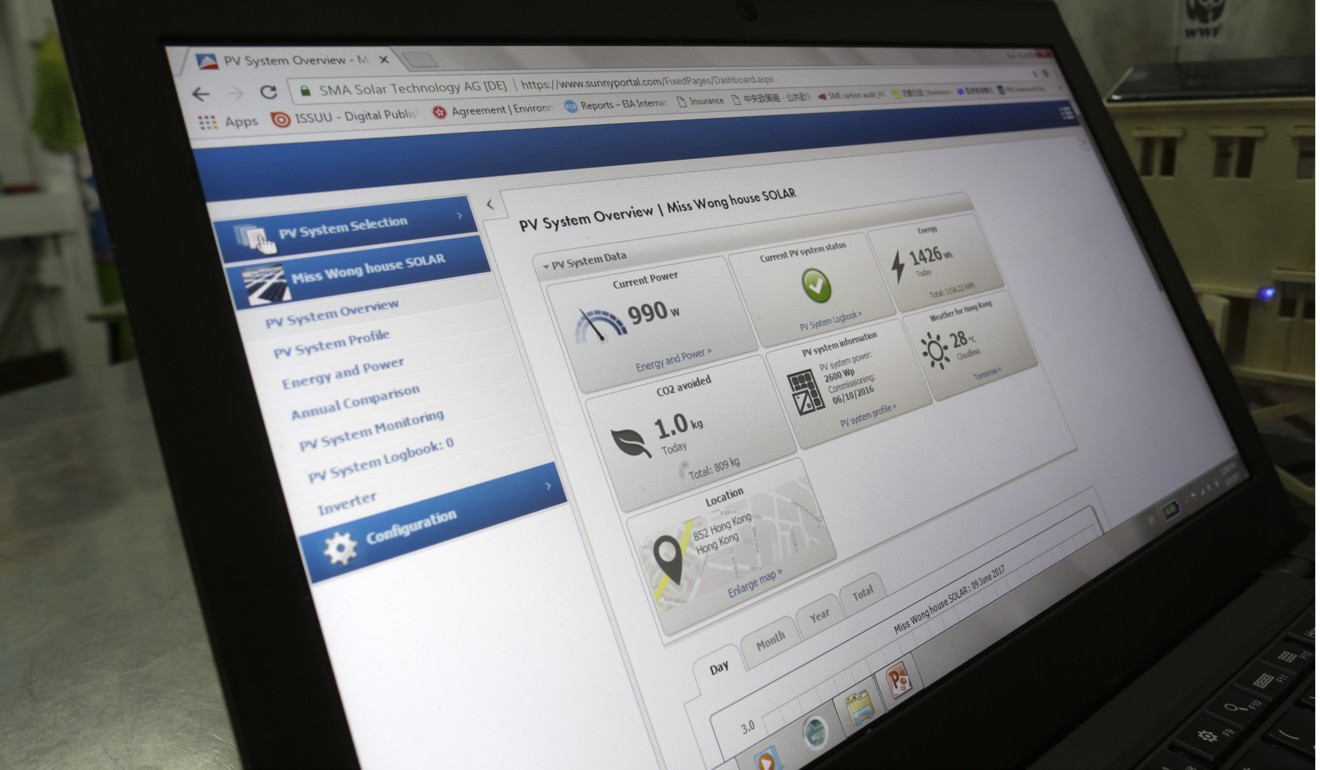

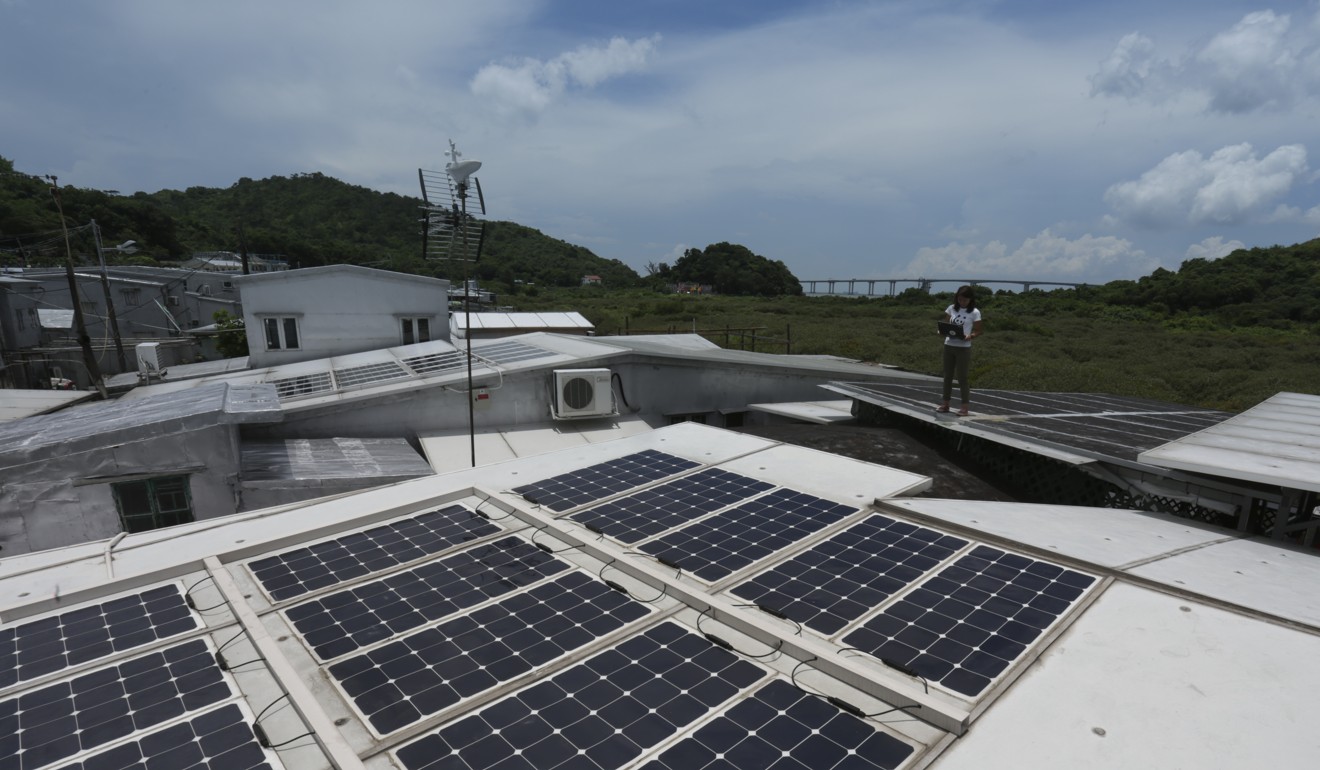

The roof of Fung Chuen-tai’s home in Tai O, a fishing village on Lantau Island in Hong Kong, has been fitted with 25 solar panels. They are wired up to an inverter in the small wooden shack that converts the direct current generated by the panels into alternative current electricity. The set-up also records how much power has been generated.

Next, the electricity is converted to 220 volts and directed to the fuse box, which distributes it to where it’s needed. If no one is at home, and all appliances are turned off, it’s released to the grid.

Since there are no payment guidelines in place to determine how much households should be paid for contributions to the grid, CLP Power gets the electricity for free.

On sunny summer days, Fung’s panels generate half the power used by the household of four – an air conditioner for 10 hours, plus lights and a washing machine, for example. In winter, they provide a third of the power output.

Hong Kong must seize the opportunity to cut fossil fuel use in favour of renewable energy

Olivia To Pui-wai, from conservation group WWF Hong Kong, oversaw the installation at Fung’s home and two other dwellings in the fishing village last September.

The initiative was a pilot project to gauge not only how much electricity could be generated, but also to test out the process a homeowner must undergo to eventually sell excess electricity to CLP, which supplies power to Kowloon and the New Territories.

Hong Kong currently gets 48 per cent of its energy from coal, 27 per cent from natural gas, and the remaining 25 per cent from an unspecified mix of nuclear and renewable energy. (The Electrical and Mechanical Service Department says renewable energy accounts for just 1 per cent.)

We are concerned about the energy future in Hong Kong. It isn’t sustainable now, and we still rely on fossil fuels and nuclear energy, which is controversial.

Within the next three years, the goal is to increase the proportion of electricity generated by natural gas to 50 per cent – at the expense of coal. Nuclear power would supply 25 per cent of the total, while “coal and renewable energy” would provide the remaining 25 per cent. No specific percentage is stated for renewables.

Yet there is great potential for solar power generation in the city. Geographically, Hong Kong is well placed for solar irradiation, or solar energy that can be generated at the standard measurement of 1,350 kilowatt hours per square metre. This compares to China’s capacity of 1,000 to 2,200kWh/m2, Japan’s 1,000 to 1,600kWh/m2 capacity and France’s 900 to 1,200kWh/m2, the WWF says.

Two years ago, Daphne Mah Ngar-yin, assistant professor at the department of geography at Hong Kong Baptist University, and her team were commissioned by WWF and Greenpeace to conduct a study on environmental attitudes and energy consumption behaviour in Hong Kong. In February, she presented the findings to the power companies, government, NGOs and other stakeholders.

“Many people were not aware of the solar power potential in Hong Kong,” Mah says. “There are perceptions among Hong Kong people that renewable energy is a remote thing. Energy is difficult to communicate because you can’t visualise it, so why care about it?” she says, admitting that it’s a highly technical and scientific subject. “But if you position it as a clean energy that will not add to air pollution, then it will get their interest.”

“We are concerned about the energy future in Hong Kong. It isn’t sustainable now, and we still rely on fossil fuels and nuclear energy, which is controversial. On the other hand, we’re not conserving energy either. We need to explore alternative energy sources,” adds Mah.

There is also a perception that renewable energy can only be generated in rural areas, but even Singapore, Seoul, London and New York are installing solar panels wherever possible. Mah says Hong Kong has plenty of areas where the sun’s energy can be tapped.

China wasted enough renewable energy to power Beijing for an entire year, says Greenpeace

“In the northwestern part of Hong Kong there are private housing estates, like Fairview Park in Yuen Long, with about 5,000 single houses,” Mah says. “We did a rough estimate and if they used their rooftops they could install 5 megawatt panels there. There are also private and village houses in Sai Kung and other parts of the New Territories.”

She says Hong Kong currently generates about 4 megawatts of solar energy per year, but the government has no specific targets for the foreseeable future. Singapore generated 71mW last year, with a target of 350mW by 2020. New York generated 30mW in 2014 and is targeting 1,000mW by 2030.

“We can move from between 4 per cent and 5 per cent to 10 per cent [total renewable energy] if we have a strong solar power policy in Hong Kong,” Mah says, citing research by the Polytechnic University. “But are rooftop owners willing to open up their roofs to install solar panels? Singapore mobilises the market for solar panels by installing them on the roofs of social housing blocks and tendering contracts to install these panels, so it’s at a low cost.”

When WWF installed the panels on Fung’s home, the conservation group spent three months testing the system to meet rigorous requirements set by the government and CLP Power in order to connect safely to the grid.

Beijing sets low wind and solar power targets in quest for sustainability

Fung’s solar experiment is now running smoothly and she only needs to go up to the roof once a week to wipe any dirt off the panels.

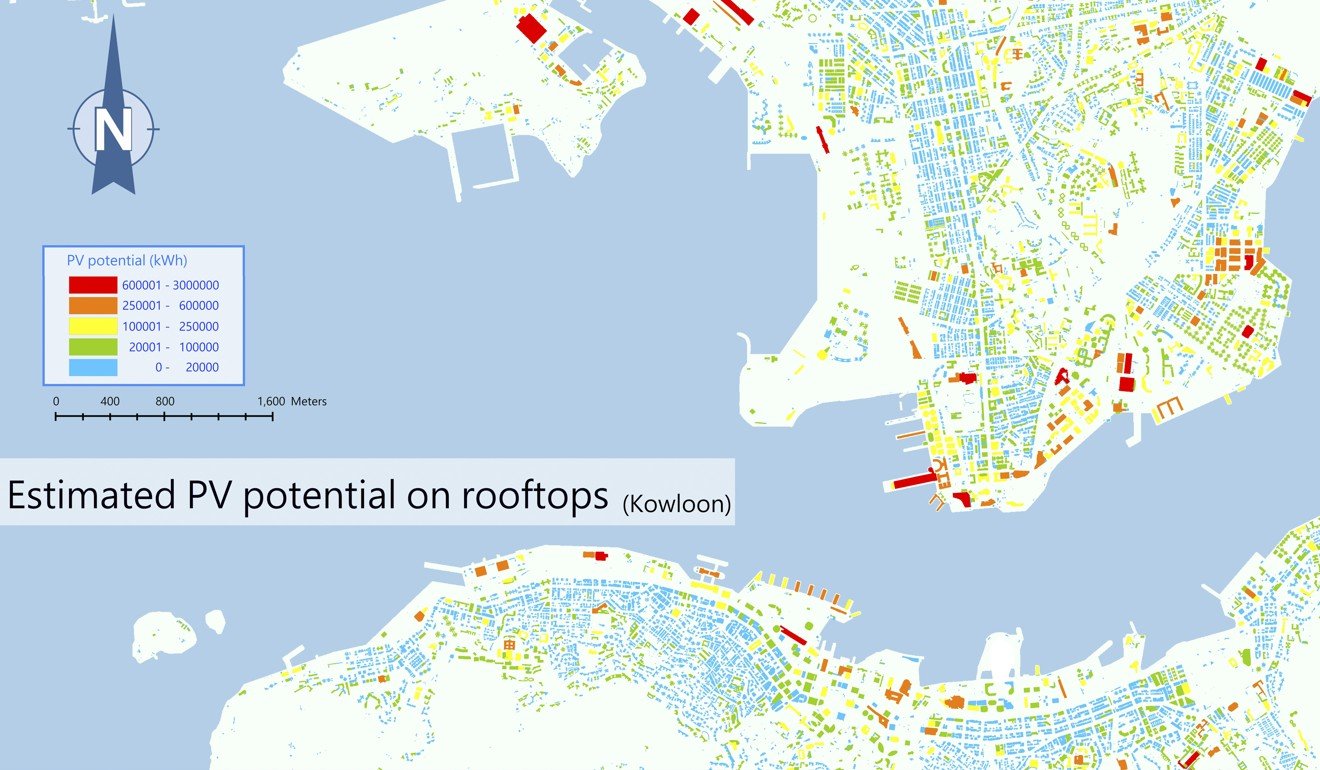

Dr Charles Wong Man-sing, from Polytechnic University’s department of land surveying and geo-informatics, conducted a study to determine which parts of Hong Kong would be best suited to capturing the sun’s rays. His team believes that renewable energy could potentially account for 10 per cent of all power generated in Hong Kong.

Wong and his team built a virtual 3D model of the city to survey the number of unused rooftop areas that could accommodate solar panels. They also took into account the anticipated number of blue-sky hours.

Solar can provide an alternative. The challenge is more than education. It’s almost like a social movement – you need more ordinary people to care.

“There are almost 300,000 buildings in Hong Kong, of which 233,000 could have solar panels on them,” Wong says. “In terms of surface area for solar energy, that’s the equivalent of 147 to 200 Victoria Parks.”

As a result, he says if all these buildings were fitted with panels, they would produce 10 per cent of the city’s total energy requirements.

Additionally, although he hasn’t researched the potential yet, Wong notes that the technology exists to install wafer-thin films on the sides of skyscrapers to capture solar energy.

Wong’s research was submitted to the government’s Central Policy Unit last year, but other than acknowledging that the report was “satisfactory”, there has been no further follow-up.

His colleague, Vivien Lu Lin, an associate professor in the Renewable Energy Research Group at PolyU, looked into the expense associated with going solar in Hong Kong, and found many challenges.

“The cost of installation is expensive because not many people have the expertise to do this in Hong Kong, so the market is small,” Lu says.

How China has embraced renewable energy and Hong Kong hasn’t, and what’s behind city’s green power inertia

The government needs to offer incentives such as subsidies, investment support, tariffs for power companies to buy electricity from individuals, or renewable energy certificates for consumers who are keen to buy green energy, but these options are not available.

“This is a missed opportunity. If you use renewable energy the benefits outweigh the initial costs,” she says.

The proponents of solar power say the government should determine a feed-in tariff to be paid by power companies to households and other property owners who generate excess solar power.

Australia set to triple solar power capacity after government awards funding for new plants

The current cost of electricity to consumers is HK$1.10 per kilowatt hour. They say the feed-in tariff should be set at a minimum rate of HK$4 per unit for at least eight to 10 years, to enable suppliers to recoup the cost of installing solar panels and passively generate income by selling back to the grid.

Under its Climate Action Plan 2030, the Hong Kong government aims to reduce carbon emissions from 6.2 tonnes per capita in 2014 to between 3.3 and 3.8 tonnes by 2030 (a reduction of 26 to 36 per cent from 2005 levels). To help achieve this, it projects boosting renewable energy generation to between 3 per cent and 4 per cent of the total.

Figures aside, enabling ordinary residents to generate and even sell electricity would give them a sense of empowerment, Mah says.

“Unlike nuclear or offshore wind farms, solar power generation allows households and small communities to contribute and have a say.

“Traditionally, Hong Kong power relied on the local and Beijing government. What is the energy policy direction? Solar can provide an alternative. The challenge is more than education. It’s almost like a social movement – you need more ordinary people to care.”