How the World Could—and Maybe Should—Intervene in Syria

Allowing the violence to go on could have worse consequences than an intervention, though only one that meets certain conditions.

Allowing the violence to go on could have worse consequences than an intervention, though only one that meets certain conditions.

In his article on possible intervention in Syria, Steven Cook has broached a subject that I agree must be raised. He forces us to confront the possibility -- he would argue the probability -- that the Western mantra of the inevitability of Assad's fall is both the triumph of hope over expectation and a cover for not taking more direct action to help the Syrian opposition. Saying it will not make it so, and as Cook points out, tightening sanctions and regional and international isolation is not having any measurable effect on Assad's calculations about his ability to stay in power. Indeed, they may even be stiffening his resistance. Cook challenges us to face alternative scenarios that will force the international community to make much more difficult choices. Suppose Assad is still in power a year from now, having killed 10 or 15 thousand of his people -- the number that his father obliterated in the city of Hama in 1982. Or suppose Syria descends into full-fledged civil war with an outgunned rebel army holding specific towns and even swathes of territory against a central government armed by Russia and Iran. Can fellow Arab states and the United Nations stand by and allow either scenario to play out?

Consider the consequences. If the Arab League, the U.S., the European Union, Turkey, and the UN Secretary General spend a year wringing their hands as the death toll continues to mount, the responsibility to protect (R2P) doctrine will be exposed as a convenient fiction for power politics or oil politics, feeding precisely the cynicism and conspiracy theories in the Middle East and elsewhere that the U.S. spends its public diplomacy budget and countless diplomatic hours trying to debunk. If you believe, as I do, that R2P is a foundation for increased peace and respect for human rights over the long term, that each time it is invoked successfully to authorize the prevention of genocide, crimes against humanity, grave and systematic war crimes, and ethnic cleansing as much as the protection of civilians from such atrocities once they are occurring, it becomes a stronger deterrent against the commission of those acts in the first place. Governments' systematic abuse of their own citizens have either caused or presaged countless conflicts around the world: the crimes against humanity perpetrated against the Jews and other minorities by the Nazi government before World War II; Saddam Hussein's systematic war crimes in his war with Iran in the 1980s before his invasion of Kuwait in 1991; the Rwandan genocide leading to 15 years of conflict in the Congo; the ethnic cleansing in the Balkans before and during the war in Bosnia, Croatia, and ultimately Kosovo; and countless cases of such behavior triggering civil war and ethnic conflict that create massive refugee flows and destabilization across entire regions. Deterrence and prevention of crimes of this magnitude is thus a force for peace.

Equally important is the age-old strategic need for credibility. If the U.S. says it stands behind R2P but then does nothing in a case where it applies, not only will dictators around the world draw their own conclusions, but belief in the U.S. commitment to other international norms and obligations also weakens, just at a time when the U.S. grand strategy is to expand and strengthen an effective international order. The credibility of the U.S. commitment to its own proclaimed values will also take yet another critical hit with every young person in the Middle East fighting for liberty, democracy, and justice.

The second scenario is even worse. A full-fledged civil war in Syria could quickly become a proxy war between Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and/or at least some NATO countries on one side against Iran, Russia, Hizbollah, and possibly Iraq and Hamas on the other. That is a deeply dangerous and destabilizing prospect. Streams of refugees will burden and potentially disrupt local politics in Jordan, Turkey, Iraq, and Lebanon. The Kurds in Iraq and Turkey and the Druze in Lebanon might join in on the side of their respective Syrian cousins. The economy of the entire region would be badly disrupted, even independent of any impact on oil prices. And Syria itself would be devastated, inviting the same power struggles and sectarian violence we see in Iraq today.

Still, intervention makes sense only if it actually has a higher chance of making things better than making them worse. In the Syrian case, a number of conditions would have to be met to satisfy this test. First, the Syrian opposition itself would have to call for some kind of armed intervention. Groups of protesters in different towns have requested international help, but the Syrian National Council would have to make a formal request. Second, the Arab League would have to endorse this request by a substantial majority vote.

Third, the actual intervention proposed would in fact have to be limited to protection of civilians through buffer zones and humanitarian cordons around specific cities, perhaps accompanied by airstrikes against Syrian army tanks moving against those cities. It could not, as in Libya, take the form of active help to the opposition in their effort to topple the government. Instead, the Arab League should work with the opposition and members of the business community and the army within Syria to craft a political transition plan that would create some kind of unity government and a timetable for elections.

Today, the Arab League proposed a plan for Assad to step down and be followed by his vice president and the formation of a national unity government followed by elections; the Syrian government dismissed it out of hand as a violation of Syrian sovereignty and "flagrant interference in internal affairs." The Arab League should next try to invite both members of the opposition and members of the Syrian business community and various minorities to work on a plan that would come from Syrian citizens as well as the League.

Fourth, the intervention would have to receive the authorization of a majority of the members of the UN Security Council -- Russia, actively arming Assad, will probably never go along, no matter how necessary -- as an exercise of the responsibility to protect doctrine, with clear limits to how and against whom force could be used built into the resolution. Finally, Turkish and Arab troops would have to take the lead in creating zones to protect civilians, backed by NATO logistics and intelligence support if necessary.

Openly raising the possibility of armed intervention does not mean that intervention is bound to occur. Much of the diplomatic activity to date has been aimed at getting Assad's supporters -- particularly the Sunni business community of Damascus and Aleppo -- to rethink their allegiances. It is a game of perceptions and assumptions, whereby the international community has tried to make Assad's fall seem inevitable and Assad himself has made clear that he will not be cowed into leaving or making real concessions. Injecting the possibility of armed intervention to protect opposition protesters into this mix, with the accompanying prospect of a much longer and much more destructive conflict in which more members of the military could defect to the Free Syrian Army, could tip this domestic political balance in favor of a negotiated deal and put real internal pressure on Assad. It is still true, however, that the credible threat of force requires an actual willingness to make good on that threat.

MORE ON SYRIA | |

|---|---|

| It's Time to Think Seriously About Intervening |

| Inside Syria's Insurgency |

| How the World Can Peacefully Intervene |

| A War Against Children |

| Assad Chooses the Qaddafi Model |

Last week the Carnegie Corporation, the Stanley Foundation, and the MacArthur Foundation sponsored a terrific conference on the next decade of R2P. Panel members discussed the pros and cons of R2P interventions to date and what we might expect in the future. During the question period after the second morning panel, former prosecutor for the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia and current International Crisis Group President Louise Arbour said that she agreed with Gareth Evans' (the former Australian foreign minister and a member of the original commission that gave rise to R2P) analysis that the preconditions for an R2P intervention in Syria were not met. Arbour said that, in terms of the magnitude of the crimes being committed in Syria (over 5,000 deaths, destruction of opposition towns) and the lack of effective alternatives other than force, the threshold for an R2P intervention was met. But she said an intervention in Syria failed the third criterion, whether intervention would do more good than harm.

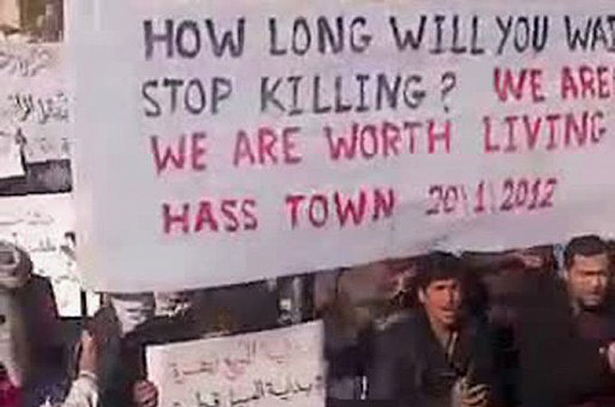

I disagree with Arbour's assessment, if in fact the conditions I spelled out above could be met. But that's not the point. She made the further point that if the international community is NOT going to intervene, then R2P includes the responsibility to tell protesters on the ground that help will not be forthcoming, so that they can make their own plans accordingly. Arbour is right. But then the U.S., Turkish, and other governments saying that Assad's fall is "just a matter of time" must be prepared to answer the question posed by protesters in the picture below honestly: "we won't be coming." But then we must also be prepared to face the consequences. In a recent Al Jazeera report, the source of the photo at the top of this page, reporter Zeina Khodr quoted one opposition figure as saying that Syria will descend into "endless chaos."

Khodr added, "Activists, however, say that armed rebellion is being fueled by the lack of action from the international community, which has made them realize they have no choice but to take up arms and fight this battle alone."