May 2007 WLT

Don’t think I believe the people erected this statue to me

because I know better than you that I commissioned it myself.

Nor do I pretend to pass into posterity with it

because I know the people will tear it down someday.

Nor do I wish to give myself in life

a monument you would never raise to me in death:

I erected this statue because I knew you would hate it.

—Ernesto Cardenal, “Somoza Unveils the Statue of

Somoza in Somoza Stadium”

Three Somozas ruled Nicaragua in the twentieth century, each a dark persona magnified and diminished by personal infamies and self‑interests that crushed their small, immensely complex nation into a mass of social, economic, and political wreckage it is still sorting out. During a familial succession unique in Latin America, backed by the gangster-like National Guard (Guardia Nacional), essentially a private army, plus dependable financial and military support from the U.S. government, the triad dominated Nicaragua from 1936 to 1979, monopolizing nearly every industry and natural resource in the country, from railroads to the skin trade, while looting it from the peaks of its volcanoes to the dirt floors of its poorest farmers. Only a deep‑rooted, relentless spirit of survival and resistance native to its citizens kept the country (the largest but poorest in Central America) from being swallowed whole.

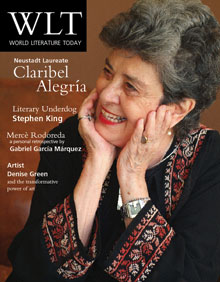

The Somozas survive in triple vision (a sort of historical triplopia), brought into focus through tales of their rise to power, shared incidents in their overlapping lives, and narratives attempting to disentangle the interconnected nightmares they wrought. Among the most engaging examples of the last is Death of Somoza, by Nicaraguan-Salvadoran poet Claribel Alegría and her husband, writer Darwin Flakoll, a grim but colorful account of the third Somoza’s 1980 assassination in Asunción, Paraguay by a covert squad of Argentine revolutionaries following the triumph of the Nicaraguan revolution.

One of many Alegría‑Flakoll collaborations (which include fiction, nonfiction, and translations), the account is a cross‑genre tour de force that weaves a mesmerizing chronicle from fact, informed speculation, historical documentation, and interviews with participants in the operation. Challenged by subject matter with potential to lapse into rhetoric or political diatribe at any juncture, the authors never allow the story to become superficial or strained, balancing their resources for the sake of a credibility. Ostensibly centered on a particular episode and individual, Anastasio Somoza Debayle (Somoza III), the work incorporates a wide range of background information, including startling details about clandestine operations.

The interviews begin with “Ramón,” commander of the seven‑member squad (four men and three women), revealed to be Enrique Haroldo Gorriarán Merlo, a founder and prominent leader of Argentina’s People’s Revolutionary Army (erp). The book then switches back and forth between his memories and those of other squad members, linked and framed by historical context, capturing the political and social moods of the period with lively energy drawn from the power and drama of the last phase of Nicaragua’s forced, macabre dance with the treacherous family that held it in a death grip for over four decades.

Why Argentine leftist guerrillas would do what one might expect Nicaraguans to do is a revealing part of the story. In 1979, in solidarity with a popular insurrection against Somoza led by the Sandinista National Liberation Front (fsln), Ramón and two other members of the future assassination team, “Armando” and “Santiago,” crossed into Nicaragua from Panama with a group of other battle‑hardened Argentine revolutionaries to join the fight against Somoza’s forces during the final weeks of combat. The uprising was an unconditional success, but Somoza got away—not good news, because he could be counted on to mount a return.

To neutralize him, Ramón suggested the assassination to his two Argentine comrades in Managua after the war. It was a wild, dangerous idea, but they agreed to move on it without informing the nascent Sandinista government, which (in this version of the story) was working to have Somoza extradited. There was no lack of desire on the part of Nicaraguans to capture or kill Somoza (it was assumed they would make an attempt), but he was living under heavy protection in Paraguay by then, and the feat could only be accomplished clandestinely from an unexpected source. Secrecy was paramount, so the Argentines decided to inform the Sandinistas only if their plan succeeded.

Completing an accurate account of the complicated operation took years, then more years passed while the authors waited for an opportune moment to publish it without creating political problems for surviving members of the squad. They shelved the manuscript several times (once, they thought, permanently), until the right moment finally came. The result was a fast-moving narrative distilled from a mountainous text.

Bolstering their argument that the work is not an apology for terrorism but the chronicle of deserved tyrannicide, at the beginning of the book Alegría and Flakoll include a list of recriminations against Somoza’s government from a 1978 Organization of American States (oas) report on the condition of human rights in Nicaragua during his final full year in power. A blistering indictment, the report condemns the government for “serious, persistent and generalized violations,” including indiscriminate bombing of civilian populations, National Guard “mop‑up” operations (viz., the execution of innocent citizens, including young people and defenseless children), abuse and murder of peasant groups, arbitrary arrests and detentions, torture, repression and imprisonment of males between fourteen and twenty-one, a corrupt judicial system, suspension of constitutional guarantees and the right to an adequate defense, suspension of the right to assembly, media censorship, obstruction of Red Cross activities, repression of priests and ministers, and hindering voting rights.

How Nicaragua—a naturally beautiful, ecologically rich country populated by strong, good-natured, inventive, industrious, creative people—came to such a pass is a remarkable, labyrinthine story that explains almost everything but the rotten nature of the Somozas.

•

Crucial to any understanding of the country, and the Somozas (ever obsequious to Washington D.C. administrations of the moment), is Nicaragua’s long, troubled relationship with the United States, which began in earnest with the 1848 Gold Rush and simultaneous Manifest Destiny–driven U.S. westward expansion, dramatically accentuated by an entrepreneurial trans‑isthmian canal plan by steamship magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt before the transcontinental railroad came into being. Cashing in on massive east‑west traffic using Nicaragua as a shortcut across Central America to the Pacific, then north by ship to California and back, Vanderbilt established a lucrative transportation line that crossed the country by boat via the San Juan River and Lake Nicaragua, then overland on a twelve-mile stretch of road to the Pacific. His plan (supported by logistical desires on the part of the U.S. government) was to replace the road with a canal, linking the coasts completely by water, significantly speeding up passage to the Pacific, and in the process bankrupting a competing railroad that crossed Panama.

The migration traffic should have enriched all Nicaraguans, but only a few well‑placed aristocrats actually benefited from the windfall, and the canal was ill‑conceived if only because there was little interest on the part of investors in what Nicaraguans thought about the scheme. Inevitable disputes led to an 1853 U.S. Marine invasion in support of Vanderbilt (the first of eleven U.S. interventions), followed the next year by a U.S. naval bombardment and Marine invasion of the Atlantic coast port of San Juan del Norte, and then, in 1855, the appearance of charismatic Tennessee lunatic and soldier of fortune William Walker with an army of mercenary filibusters from California. Walker, based in San Francisco, gem of the Gold Rush, took sides in a civil war between Nicaragua’s Liberal and Conservative parties, invited to do so by the Liberal Party (liberal in name only, and future party of the Somozas). He captured the city of Granada, Conservative stronghold and gem in its own right, and promptly—with tacit approval of U.S. president Franklin Pierce—decided to take over the country. He burned Granada down to the nails, planted a sign that read “Here was Granada,” declared himself president of Nicaragua, made English the official language, and legalized slavery.

He was, in part, acting clandestinely on behalf of interests in the U.S. South, under increasing political pressure in pre–Civil War days and anxious to find safe havens for its threatened slave‑based economy. Walker’s audacity and success caused the Liberals and Conservatives, as well as the usually warring other nations of Central America, to join forces and drive him out, an effort that led to a promising but brief period of unification in the region.

By then both the United States and Britain were deeply invested in the potential riches of Central America, and Nicaragua, after hard-won independence from Spain earlier in the century, found itself in their crosshairs. Against Nicaraguan interests, the competing powers signed the bilateral Clayton‑Bulwer Treaty in 1850, essentially divvying up the country, but they still competed. During the Walker affair, Britain (along with Vanderbilt) helped finance the filibuster’s Conservative opponents, while the U.S. government supported Walker and his Liberals. In the end, if only because of proximity, the U.S. became the dominant outside influence in the region by the turn of the century.

In the early 1900s, President Theodore Roosevelt decided to finally dig the isthmian canal, but not through troublesome Nicaragua. It would be in Panama, though first he needed to liberate that province from Colombia, which he accomplished via military occupation, creating the Republic of Panama, which in turn granted the U.S. exclusive canal rights. It was shady but profitable business, and when Nicaragua reacted by planning a German‑financed canal of its own to compete, the U.S. stirred up a rebellion, invaded again, and came away with a Nicaraguan canal‑rights treaty that blocked any possibility of competition.

In 1912 the Marines invaded Nicaragua again and stayed until 1933, finally driven out in a brutal six‑year guerilla war waged by the ragtag forces of populist general Augusto César Sandino, Nicaragua’s most famous hero, and name source of the FSLN. Unfortunately for Nicaragua, Sandino’s victory paralleled the rise of the first Somoza, Anastasio Somoza García. Sandino’s motives were grounded purely in ridding the country of foreign dominance, but Somoza I’s political and economic ambitions were matched only by his proclivity for greed and brutality, traits that would be inherited and refined by his sons, especially the youngest, namesake Anastasio Somoza Debayle (Somoza III), a West Point graduate known as “the last Marine,” said to speak English better than Spanish.

•

Anastasio Somoza García (Somoza I), known by the diminutive “Tacho,” ruled from 1936 to 1956. Intelligent, tremendously ambitious, and irascible, with a persuasive but sadistic streak, he was the son of a wealthy coffee grower, sent to Philadelphia as a young man to live with relatives and complete his education at the Pierce School of Business Administration. Two seemingly innocuous things happened there that set the course of Nicaragua’s future: he learned fluent English, skillfully peppered with slang and colloquialisms that would later endear him to U.S. Marines and authorities occupying Nicaragua, and met his wife, Salvadora Debayle Sacasa, from one of Nicaragua’s wealthiest, most powerful families, and niece to future Nicaraguan president Juan Bautista Sacasa, who would play a key role in Somoza’s rise.

Returning to Nicaragua, Somoza joined a Liberal Party revolt in support of Sacasa, had a brief (undistinguished) military career, held several government positions through family connections, then joined and quickly rose through the ranks of the National Guard, a so‑called constabulary force organized and trained by the Marines. After the Marines left, Somoza, handpicked by the U.S. to command it, moved swiftly to consolidate control over the organization and began his ascent to absolute power. In 1934 he arranged peace talks at the presidential palace between Sandino and, by then, President Sacasa (soon to be overthrown with a coup de chapeau and rigged election). Somoza did not attend—he went instead to a poetry recital. After a celebratory banquet, an unsuspecting Sandino, his brother Sócrates, and three of his best officers, all under protection of presidential amnesty, were arrested by the National Guard outside the gates of the palace, taken to a wooded area, machine‑gunned, and buried in a secret grave.

Somoza punctuated the assassination by ordering a massacre of men, women, and children in rural areas supportive of Sandino, after which he encouraged the National Guard to suppress and harass the general public as they saw fit, his way of solidifying their loyalty and alienating them from real or potential Sandino supporters—basically the entire population, excluding the wealthy.

An official photograph from a 1939 state visit to Washington, D.C., shows Somoza standing next to a hatless President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who is smiling broadly at something or someone in front of him. Dressed identically in morning dress (formal black tailcoats and gray striped trousers), the two presidents are posed with a group of military and civilian dignitaries, Eleanor Roosevelt and Somoza’s wife, Salvadora, standing stiffly behind them, a Marine honor guard in the background. An unhappy Salvadora glares directly at the camera, while Eleanor seems to be watching Roosevelt’s back. Somoza is serious, distracted, top hat and gloves held in his left hand like a tray, staring outside the scene to his left while the crippled FDR gamely holds himself upright on the arm of a smiling Army officer in full regalia to his left.

Another photo from the same trip shows Somoza and FDR in the back of an open limo wearing top hats, Somoza looking wary and Roosevelt uncomfortable. His administration supported and rewarded Somoza, but he privately despised him, illustrated by the famous misogynistic (reportedly apocryphal) comment he made when confronted by the horror of Somoza’s cruelty: “He may be a son of a bitch, but he’s our son of a bitch,” a terse description that sums up the self‑interest of U.S. support for any number of brutal dictators in modern history.

But the most famous of all Somoza photographs from the period is a smile‑free 1934 reconciliation portrait with Sandino that might be called the ultimate embrace. A chubby Somoza wears a tight military uniform complete with Sam Browne belt, the peak of his service cap pushed slightly upward for a clear view of his round, corpulent face. Wiry and shorter by inches, the darkly tanned, romantic‑looking Sandino, jacket open, bandana knotted around his neck, and wide‑brimmed campaign Stetson cocked toward Somoza, has stretched his right arm up and around Somoza’s shoulder, hand resting on an epaulet. Somoza’s left arm passes under Sandino’s right, the tips of his fingers (if they are his fingers) barely visible, like something crawling over Sandino’s left shoulder. It’s said that somewhere under Sandino’s coat is a pistol. He was wise to be careful. He would be murdered a few days later.

Tacho, on the other hand, would last another twenty-two years, until 1956, when he met young poet and journalist Rigoberto López Pérez during a party at the Workers’ Social Club in the colonial city of León. Somoza was in León running for reelection as president, though there was no question who would win. The victory margin of his first election two decades earlier was roughly 107,200 votes to 100 and served as a model for the whole Somoza era. Photographs from that first campaign show him trotting around on a white horse in military uniform, surrounded by his thugs and waving an American flag. It was window dressing, just like the event at the Workers’ Social Club.

Mixing fact and myth as all epic tales do, the popular story goes that Rigoberto López Pérez left a note for his mother explaining he was off to El Sesteo, fabled corner café (then and now) facing the plaza of the Catedral de León, largest cathedral in Central America and resting place of Nicaraguan poet Rubén Darío. He was going there for his favorite dish (and specialty of the house), chancho con yuca, a local delicacy, but whether he made it or not is a matter of conjecture, though the rest of what he did that day is history. Wandering León’s narrow colonial streets to the nearby Workers’ Social Club, he slipped past the National Guard and shot Somoza point-blank on the inner patio with three poison‑tipped bullets. Killed instantly in a blizzard of return fire—numerous bullet holes still pock the scarred walls of the club—the poet knew his fate beforehand, so also left a sealed letter for his mother, a moving explanation that what he did was what any Nicaraguan who loved his country should have done a long time before. He later become a hero for the FSLN and an inspiration for the Nicaraguan revolution.

Somoza lingered for days, but the future was already plotted. His oldest son, Luis Somoza Debayle, was primed to succeed him as president, which he did almost immediately, and his youngest, Anastasio Somoza Debayle, was in place as commander of the National Guard, no more than a private mafia by that point.

The youngest Somoza’s nickname was “Tachito,” diminutive of his father’s “Tacho,” which made him the diminutive of a diminutive, but he was corrupt and violent beyond the limits of anything his brother or father could imagine, willing to kill people wholesale and bomb his own cities for the sake of power, and in the end would prove to be the worst of them, which by Somoza standards actually made him the best.

But before he could mount the white horse, there would be a decade for his brother Luis, who would rule, as his father did, through a combination of official titles (“President” Somoza), backroom manipulations, puppet presidents, and outright strong‑arm tactics. Considered a milder, more businesslike leader than his father, Luis maintained a smokescreen of reform that pleased the U.S., but he was still a dictator and, though never as infamous as his father and brother, always a Somoza. His brand of “democracy” had less in common with democratic principles than rats do with terriers, who at least recognize their objectives well enough to chase them. As with all three Somozas, elections were fixed during his tenure like boxing matches, his supposed commitment to modernization and economic reform (his one claim to Somoza uniqueness) applied only to the privileged (a tiny minority), and his main political achievement seems to have been an amendment to the constitution to prevent his psycho brother from running for president.

Nothing Luis Somoza did made any difference to anyone but himself. After a decade of pretending to run the country like a CEO while fending off his younger brother’s thirst for power (there are rumors Tachito planned to have him assassinated to clear the boards), he had a heart attack in 1967 and put the final Somoza chapter into play. As soon as Luis died, Anastasio was “elected” president, and he would run Nicaragua like a man playing piano with a baseball bat.

Picking up where his father left off, Somoza III and his thug army pillaged the country until a natural catastrophe brought everything about him into terrible focus for Nicaraguans. In 1972, two days before Christmas, a devastating earthquake struck Nicaragua, killing thousands of people and destroying vast stretches of Managua. Rather than help his people, Somoza began systematically looting the international relief that poured in. He scooped up land on the cheap and resold it to his own government for relief camps at ten times the price, sold donated emergency items on the black market, used reconstruction money contributed by the U.S. government to buy cement from his own cement factories at highly inflated prices, and on and on. He couldn’t spare a moment for his own people, but in the chaos took time to ensure that billionaire Howard Hughes, ensconced at Somoza’s pleasure on the top floor of Managua’s Hotel Intercontinental (his windows blocked by tinfoil, and wearing Kleenex boxes for shoes), was safely shepherded to the airport and out of the country with his own henchmen. If any Nicaraguans doubted the nature of Somoza’s character before the earthquake, all doubts were buried in the rubble of Managua. The beginning of the long ending of the dictatorship was at hand.

Lacking any effective political successors of his own, Sandino faded into history after his murder but was hardly forgotten. His name and idealism were resurrected in 1961 by the FSLN, specifically organized to overthrow Somoza. After more than a decade of largely ineffective actions against the regime, coupled with factional infighting and general disorganization, they pulled off a successful 1974 guerrilla operation in Managua that put Somoza on notice, after which the organization slowly began to coalesce. In January 1978, the Somoza‑linked shotgun assassination of Pedro Joaquín Chamorro, popular publisher and editor of the opposition newspaper La Prensa, while driving to work through the earthquake ruins of Old Managua, sparked a national insurrection that exploded into a war of liberation, the Nicaraguan revolution. Eighteen months later, in July 1979, a Sandinista-led triumph matched and exceeded everyone’s expectations, but a major piece of the victory went missing—the last Somoza escaped unharmed.

•

That is where Alegría‑Flakoll’s Death of Somoza picks up and ends the saga. In the face of overwhelming defeat, Somoza resigned, loaded three airplanes with cash, gold, and property (including a clutch of parrots and the zinc coffins of his father and brother), and escaped to Miami with key officials of his government. He left a devastated nation in his wake: 50,000 dead (80 percent civilians killed by his indiscriminate air bombardment of major cities), 100,000 wounded, 40,000 orphans, and 150,000 refugees chased over the borders into Honduras and Costa Rica. In his final days he looted the banks, leaving behind (because he couldn’t get at it) barely enough money to keep the country afloat for two days, a universe of mortgages, and a foreign debt to the tune of $1.6 billion, money leveraged to move resources out of the country.

In Miami he was immediately informed by President Jimmy Carter’s administration that he was not welcome. He fled to Great Exuma in the Caribbean searching for refuge, then to Paraguay where he was granted luxurious asylum by fellow dictator and Nazi war-criminal guardian, President‑General Alfredo Stroessner. There his fate waited in the chambers of an M‑16 and a bazooka. As Eduardo Galeano recounts in Century of the Wind, when asked by journalists in Managua who assassinated Somoza, Sandinista comandante Tomás Borge responded to the mystery with the title of a seventeenth-century play by Spanish playwright Lope de Vega, eponym for a village that took collective responsibility for killing its own tyrant: “Fuenteovejuna,” they replied when asked who killed him. Everybody.

San Francisco