Keeping the Window Shut: Britain’s Diplomatic Maneuvers

Great Britain was a global power during the time of the Greek War of Independence, with mercantile and naval interests in practically every corner of the planet. This position would not only inevitably force the British government to choose a stance about the conflict in Greece, but would also cause the other European powers to vie for British support of their particular bloc. At the onset of the war, the British position was decidedly pro-Ottoman. However, it was clear to most British diplomats that this was not out of any particular love for the Turks, but was rather born out of a fear of Russian expansion. The main fear in Britain was that the Russians would effectively take control of Greece and use it as a base to threaten British interests in the Mediterranean, cutting off India from the rest of the empire in the process. The British were also the largest trading partner of the Ottoman Empire, and they were anxious that increased Russian tariffs could stifle the lucrative trade setup in the Aegean and Levant regions. Another reason for the British stance was that they held the Ionian Islands (Greek: Ιόνια νησιά) off the coast of northwestern Greece, and they didn’t want the fighting to spill over into their territories. For the British, the war was a diplomatic balancing act of trying to keep Russia contained while advocating for the quickest possible routes to peace via attempted mediation of peace talks between the combatants.

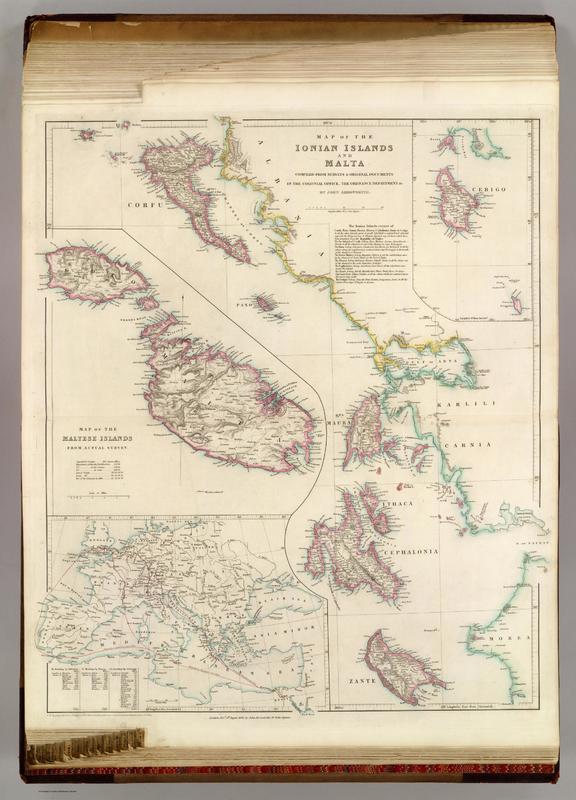

The map above shows the British possessions in the Mediterranean during the time of the Greek War of Independence. On the left is the Maltese Islands, while on the right is the Ionian Islands, which hug the western coastline of the Greek mainland. From north to south, the major islands are Corfu (Greek: Κέρκυρα), Paxo(s) (Greek: Παξοί), Lefkas/Santa Maura (Greek: Λευκάδα), Ithaca (Greek: Ιθάκη), Cephalonia (Greek: Κεφαλονιά), and Zante (Greek: Ζάκυνθος). The last Island of Cerigo (Greek: Κύθηρα) is located in the top right corner of the map. The British gained the Ionian Islands after the Napoleonic Wars, and they were a point of contention during the Greek War of Independence as the English administration on the islands heavily discouraged local Greeks from joining the separatist movement in the Morea.

The expected outcome of the war was that the Ottoman sultan’s armies would swiftly crush the rebellion, and that the status quo would return. But, the British saw that the longer the war went on, the more of a liability it would become. A more protracted fight would leave more room for direct Russian involvement, which is exactly what the British feared most. The prospect of ending the war in Greece as soon as possible, even if it meant aiding the Greeks, started to become more and more of a consideration. After both sides refused to talk about limited peace deals with British mediation, the Britons teased the idea of recognizing Greek independence in order to scare the Turks into taking the talks seriously. Despite the fact that the British used less religious rhetoric than other nations, the intervention of Egypt and the rumor that the Egyptians planned to resettle the Morea with Muslims allegedly greatly disturbed British diplomats and common people alike. This eventually led to the British distancing themselves from Ottoman support, which was predictably not well received by the Porte (“The Porte” being the popular contemporary term for the Ottoman central government). Slowly, Greek blockades were recognized, and a temporary alliance was formed with Russia, on the condition that the tsar promised not to take any Ottoman territory during the conflict. The pact would eventually include the French, and the three nations would become involved directly against the Ottomans, decisively defeating them in the naval battle of Navarino (also known as Pylos - Greek: Πύλος) in 1827. This victory legitimized the Greeks in the international community and paved the way for the establishment of an internationally-recognized Greek Kingdom.

The above painting shows two British sailing ships engaging one Turkish and one Egyptian ship. The Turkish and Egyptian vessels on the left and right bear a red flag with a white crescent, while the English ships in the center have white flags with a blue and red cross, respectively. More ships can be seen in the background. Smoke and fire billow from the Turkish ship on the left. In the foreground, there are sailors clinging to the remains of a presumably sunken vessel. This painting bucks the trend of heroic and romantic art of the early 19th-century and portrays a horrifying and chaotic battle scene. The battle of Navarino resulted from the decision of Britain, Russia, and France to end the Greek war by fighting against the Ottoman Empire. The battle was a resounding success for the pro-Greek alliance, and it saved the fledgling Greek state from collapse.

Maintaining Monarchy: Austria’s Reaction

Preachers and Politicians: America’s “Greek Fever”