This past weekend, Europa Laica (Secular Europe), a non-profit organization committed to the promotion of secularism, the secular state, and the separation of church and State in Europe, launched its first conference after 15 years of initiation. The conference took place in Madrid, same city where the organization’s headquarters are located, and it culminated with the condemnation of the agreements between the Spanish government and the Holy See. The arguments were that the instrumentation of religion or religious values into the sphere of politics was a source of favoritism in governmental representation towards the catholic faith and that it was ultimately detrimental for democracy, as it “pretends to appropriate over the public sphere and impose itself over everyone’s consciousness,” while “secularism… predicates tolerance; that every citizen can choose under freedom, without any sort of interference.”

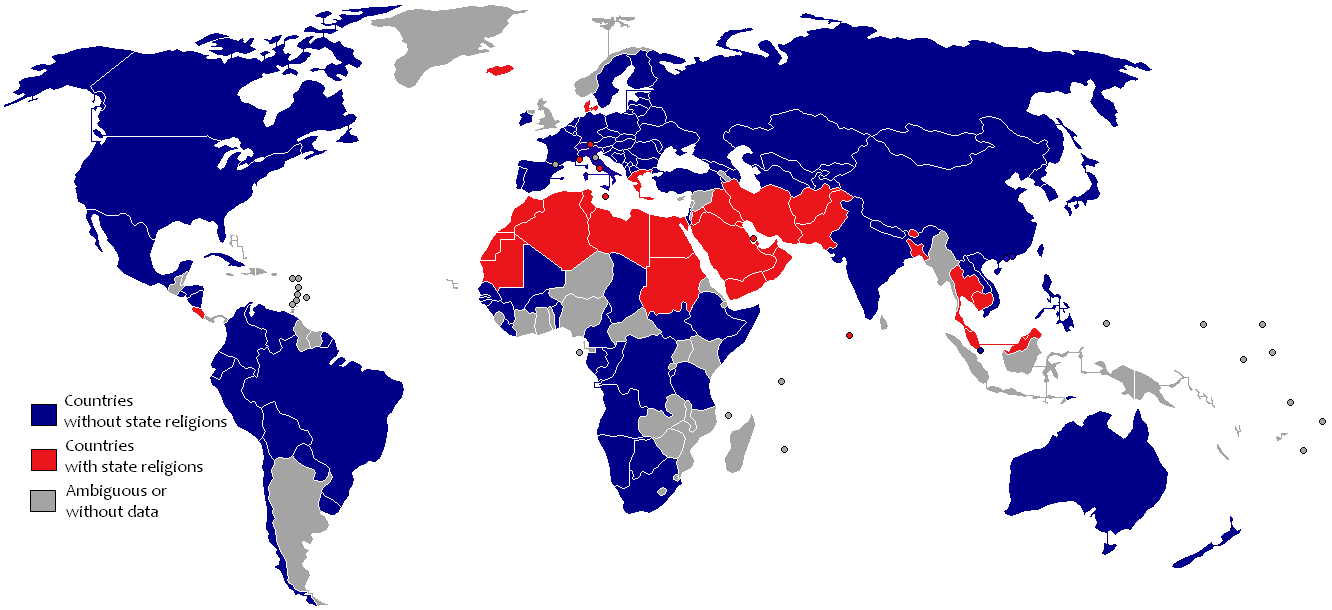

With this, the receding role of religion within Western politics continues to take its path forward. Although the conclusions to which the committees arrived are yet to materialize into legal terms, the event serves as another gesture for the growing secularization of the nation-state, and for the further de-politicization of religion within the public sphere. However, looking closer at these secular practices shaping modern governmentality, the position of religion within contemporary liberal discourse seems to be depicted as almost inherently harmful, and these conceptions have only spread and imposed themselves even further to other regions of the world.

Nevertheless, as prevalent as this model is within international politics, gestures like these only reveal the limitations of liberalism’s modularity in the Global South when it attempts to present itself as adaptable and deeply ahistoric. Indeed, and quite contrary to this Western conception, religion in many countries of the Global South has actually been politicized and instrumented in specific political projects in order to enhance democracy and civil rights, as well as to mobilize individuals against oppressive systems and define identity. For example, the role played by the catholic church in the Philippines leading up to the overthrow of ex-dictator and ex-president Ferdinand Marcos in 1986, centered the Christian faith within the processes of social and political mobilization and as a big actor for the freedom and democratization of the country. In other countries such as El Salvador or Palestine, Liberation Theology has allowed poor and marginalized communities to utilize religion as political tool in order to make their voices heard in a bottom-top scheme; often leading to successful revolutions or to democratizations of power. Perhaps one the most prominent cases; Indian mobilizers against the United Kingdom’s dominion over British India conflated Hinduism and Islam with anti-colonial nationalism as an effort to assert self-determination and democracy in what today is India, Burma, Ceylon and Pakistan, This said, it is evident that religion in particular areas of the Global South has played a deep role as a principle for political consciousness and activism–as well as an enhancer of democracy–as it has contributed to the formation of national identity and anti-colonial nationalism, and other forms of democratic expression.

Viewed from this standpoint, Europa Laica’s claim about the detriment of religion to democracy is just too simple to hold valid, as democracy actually takes multiple forms and interplays in different scales that have had both positive and negative effects on citizens’ participation into politics. In other words, although it is true that religion has a heavily undemocratic and oppressive nature, one cannot deny that religion has also played a fundamental role for the consolidation and mobilization of civil society, and even more so when it incorporates collective histories of community and kinship into its framings Then, instead of uplifting the Western liberal framework that condemns religion as a universal model of development, one would first need dive into the question of how the (mis)usage of religion into politics is in itself a result of the dynamics played out by constellation of cultural particularities and unequal power relation within and outside of a specific territory. Undoubtedly, the ways in which particulars raise their religious banners for political purposes heavily depend on the complexities of the nation in question. Therefore, an analysis of these causalities must account for the consequences of foreign intervention or globalization, the social and global hierarchies that play out in their respective communities, as well as incentives for political contestation from local groups to resist their struggles in order to effectively capture the socio-political factors that are being translated into these religious-political discourses.

This said, before imposing universalizing claims into the models of government, liberal discourse needs to scrutinize generalizing claims that are based on erased histories, and cease to universalize Western history through institutional-legal frameworks in the Global South. The complexities that shape the ways in which religion is instrumented in particular communities are as valid and legitimate as the West’s narratives, and these must be addressed in order to have a more comprehensive understanding of religion’s effects in the public sphere. Thus, the creation of spaces for healthy cultural, religious, and political conversations outside of the United States and Europe is essential for the reaffirmation of secularism in the world, and these must channel towards more inclusive and democratic practices that are also sensitive to collective histories, as well as to domestic and global forces.

Featured image source: Propel Steps

Be First to Comment