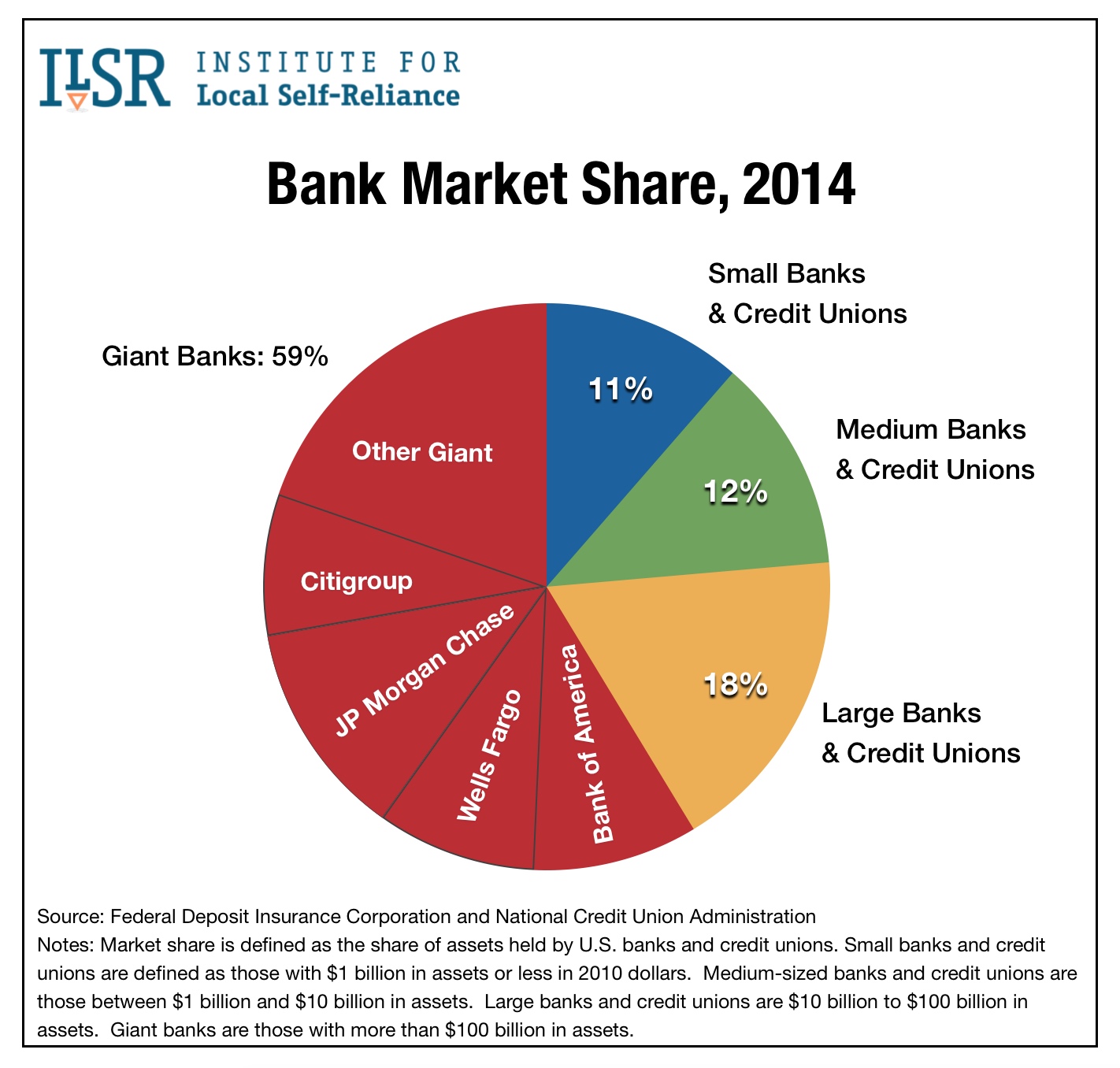

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Tackling one of America’s most dire, pressing issues, Congress turned its attention in March away from passé, low-stakes issues like gun control and immigration to — you guessed it — banking reform. By May 22, the House passed the duplicitously-named Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act (EGRRCPA), a law that will roll back aspects of the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act, weakening the law by relaxing regulations on banks with assets less than $250 billion. (Such banks somehow constitute mere “medium-sized” or “regional” banks; only a dozen American banks surpass $250 billion in assets, with the Big Six – think JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, etc. – each holding assets over $750 billion. So Congress has essentially taken pity on small banks of $100 billion.) The bottom line is that Congress reduced banking oversight on all but 12 banks in the country, and in the long run, such deregulation increases the likelihood of another financial crisis and permits larger banks to operate with less oversight, enabling them to take greater risks than they otherwise could.

The first challenge in the EGRRCPA debate is that banking regulation is poorly understood; you wonder, for instance, what were Dodd-Frank and Glass-Steagall, really? Dodd-Frank, enacted after the 2008 financial crisis, boosted bank oversight and increased requirements that would make banks more stable, including uniform thresholds for how much capital banks must keep on hand (rather than loaning out) and stress tests they must pass. (Stress tests are basically assessments of how a bank would fare in the event of a financial downturn.)

Similarly, Glass-Steagall, passed in 1933 during the Great Depression, requires banks to keep their safe and speculatory assets separate by dividing their commercial and investment banking. Commercial banking is likely most of the banking you have ever done – checking accounts, deposits, mortgages, etc — while investment banking is the risky side of business that brought on the 2008 financial collapse when complicated financial investment instruments began to fail.

There is certainly debate about how effective Dodd-Frank and Glass-Steagall have truly been, but many analysts think they have at least helped stabilize the financial sector and prevented risky behavior. A 2017 study by the Brookings Institution, for instance, found unequivocally that “through these and other reforms, the financial sector is much safer today than before the crisis.” And the popular complaint that Dodd-Frank has burdened banks and hurt profits strains credulity: In 2017, Bloomberg noted that the 10 largest U.S. banks saw nearly record-setting profits, and according to Politico, “even community banks, which the bill’s backers say they’re most concerned about, are making money.”

So was there really any appetite for deregulation? Apparently so: The bill passed in the Senate thanks to 16 Democratic defections (plus Independent Angus King) and universal Republican support. Democratic senators up for reelection in states Trump won felt pressure to contribute to a bipartisan legislative win they could campaign on, and (so the reasoning goes) voting for banking deregulation helps moderates appeal on more conservative turf (inexplicably). According to the Washington Post, however, some of the Democratic senators who voted for EGRRCPA have also received $100,000 or more in campaign contributions from the financial sector, with Senators “Heitkamp, Donnelly and Tester becoming the top three Senate recipients of donations from commercial banks so far in the 2018 campaign cycle, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.”

Progressives were livid — arguably, rightly so — that their Democratic colleagues handed conservatives a free victory, supporting deregulation without exacting any concessions: Senator Elizabeth Warren castigated the bill as “Washington working for the rich and powerful, not for the American people.” Senate leadership did not whip opposition to the bill, largely because Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (himself a New Yorker disinclined to displease Wall Street) knew his members are caught between a rock and a hard place: with Warren attacking on one flank and potential 2018 Republican challengers on the other, moderate Democrats were damned in any case, and Schumer permitted defections in the hopes of saving Democratic senate seats come November.

And moderates were not without rationale: proponents of the legislation note that “small and regional banks have complained that Dodd-Frank has put them under an unfair supervisory squeeze, punishing them for the sins of Wall Street,” according to the Washington Post. Supporters of deregulation contend that excess regulation on community banks has curtailed lending, preventing more Americans from getting loans and ostensibly dampening economic growth.

Theoretically, EGRRCPA could reduce scrutiny and relax regulatory controls on regional banks, particularly by rolling back the controversial Volcker Rule, applying it only to the very largest banks. (The Volcker Rule works similarly to Glass-Steagall, prohibits banks from speculating with funds from their own accounts and proscribes some dealing with hedge funds, amongst other things.) Dodd-Frank also set an unpopular threshold for systemically important financial institutions (SIFIs) at $50 billion in assets, which bipartisan critics (and even Dodd-Frank’s authors) consider too low.

The new threshold, however, will be $250 billion, much higher than most Democrats favor, and the magnitude of the changes is its central flaw. Although backers of the law contend that banks with assets less than $250 billion pose no systemic risks, banks’ “anticipation of bailouts encourages [them] to invest, making bailouts more probable and crises more severe,” according to research from the Federal Reserve of Minneapolis. Because banks know to expect bailouts if they default for the same reasons as their competitors, they take similar risks and increase the chances that a handful of these “not systemically important” regional banks would default together. As though one $250 billion bank’s default would not be bad enough, this correlated default pattern demonstrates how a few banks could rationally turn one market downturn into a $1 trillion default or collapse.

Perhaps a $125 billion threshold — a threshold retroactively favored by Barney Frank himself — could have liberated smaller banks without substantially increasing systemic risks, yet even the $250 billion threshold is insufficiently generous for House Finance Services Committee Chair Jeb Hensarling, who has indicated the House will seek to deregulate the banking industry even further than did the Senate bill. Paul Ryan has also suggested the House will push to further deregulate the financial industry, particularly seeking to extend relief to Wall Street in addition to community banks.

The other key component of EGRRCPA is the increased discretionary role of the Federal Reserve, America’s central bank. Ezra Klein of Vox cites “Gary Gensler, the former head of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, [who] dryly noted in a letter to the Senate banking committee, ‘laws and regulations generally are better when they are applied consistently.’” Handed wide-ranging regulatory powers and responsibilities by Dodd-Frank, the Fed will additionally “have discretion to apply other individual enhanced prudential provisions to these banks” according to the Congressional Research Service. According to Klein, the problem with a wording change requiring individualized (rather than uniform, automatic) supervision from the Fed is that “it gives the banks’ teams of high-priced lawyers more power to tie up the Federal Reserve in court by arguing that the regulations are not sufficiently tailored to their situation.”

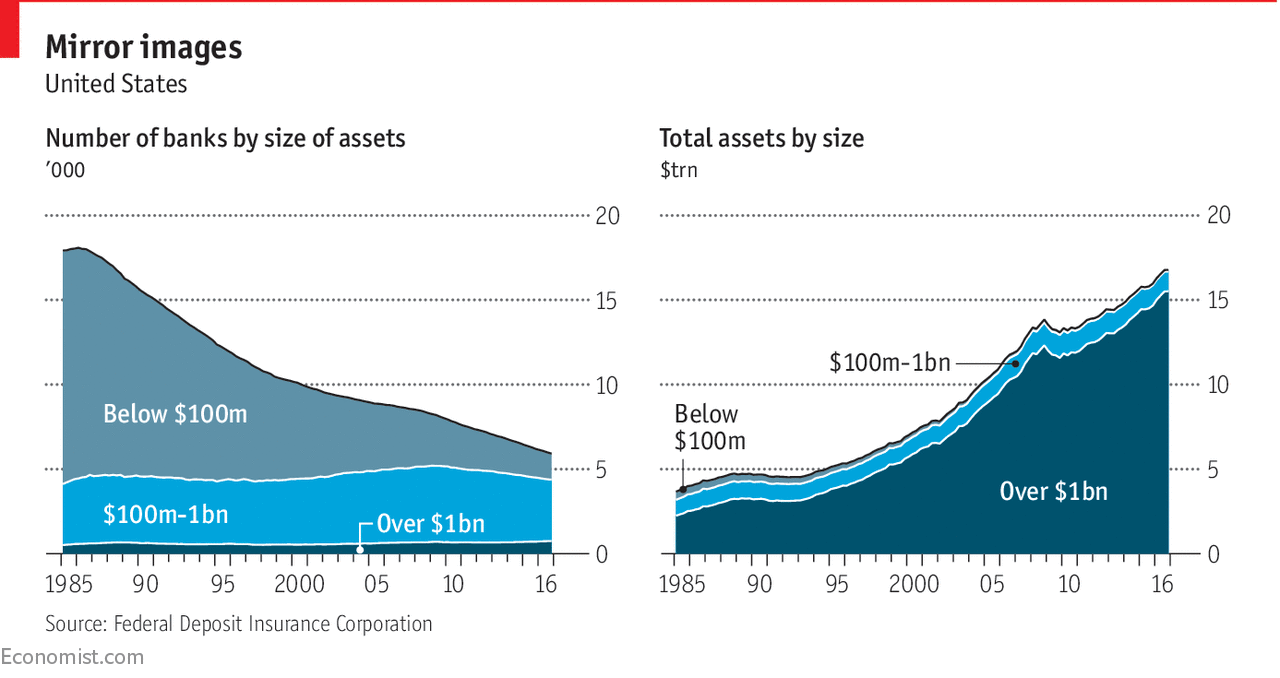

Source: The Economist

The crux of the matter, however, is simpler than the finer points: America’s banks do not need greater freedom to speculate and take risks. Even if Dodd-Frank costs the (entire) banking industry $10 billion in compliance costs (the highest estimate), that is but a pittance next to the staggering tens of trillions of dollars the industry manages; moreover, it is banks – not American taxpayers – who ought to bear that regulatory burden. Dodd-Frank, for all its flaws, demands that banks prove they are resilient to crisis, forcing them to act in ways that would avoid one. Even if regulation makes banks less profitable, which appears doubtful, the banking industry is not suffering, and Americans deserve not to suffer at its hands ever again.

Featured Image Source: American Banker (House Finance Chairman Mike Crapo (left) and Senators Jeb Hensarling (center) and Bob Corker (right) were key proponents of the EGRRCPA.)[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Be First to Comment