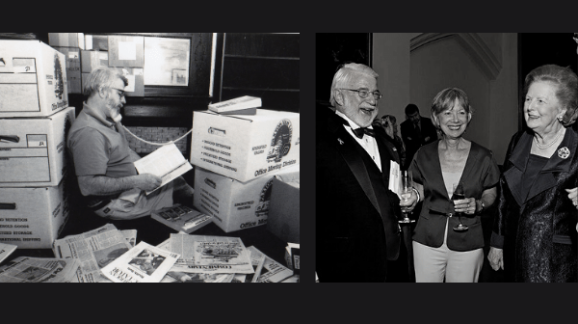

Labor of Love: A Fred Smith Story

Edited by Kent Lassman, Amanda France, and Ivan Osorio

INTRODUCTION

Everyone has a Fred Smith story. Often there is a telling detail coupled to an adjective that is both complimentary and ambiguous enough to draw the listener in for more. Charismatic. Brilliant. Peripatetic. Fun. Entrepreneurial. Charming. Generous. Willful. There are the stories about searches for ice cream sandwiches and Oreo cookies. Travel to foreign capitals. Mentoring. Partnerships with unexpected allies. And, of course, the time he hung up the phone on a cabinet official.

He has been variably called maddening, crazy, unrealistic, idealistic. He believes in institutions and an unbounded capacity for mankind to improve, but not to perfect, life and our relationships. Above all, he is a friend, even if you haven’t met him yet.

What you hold in your hands is a labor of love. It is an apt term, labor of love. In three short words, it summarizes Fred’s approach, his contagious passion, to a fruitful career.

This volume is a window into the various contributions he has made to the heady realm of ideas. Created to celebrate his 80th birthday, it is also the result of suggestions from friends, former colleagues, and admirers on how to distill the ideas that are most closely associated with Fred’s successes in public life. His work would have been so much less if not for the deep relationships created along the way. In its way, it is Fred Smith’s story.

Fred Lee Smith, Jr. was born December 26, 1940, in Alabama and raised in rural Slidell, Louisiana. There, on the northeastern shore of Lake Pontchartrain in St. Tammany Parish, Fred’s curiosity first took flight. The eldest of five children, he is a product of the bayous, where faith and family are the anchors of place. Today the popular conception of the World War II-era South brings to mind rigid antebellum class structures and nostalgia for rural life that is not typically shared by people who actually lived in a pre-industrial, rural community. But that is not the cultural mindscape of Fred Smith.

He imbibed a deeply egalitarian ethic—you are no better than me and I’m certainly no better than you. New Orleans, home of his alma mater Tulane, was a cosmopolitan melting pot where things were made, traded, loaded, shipped, and exchanged. Music literally rang out in the streets and food holds a near-religious status. Fred met his future wife, Frances Bivona, at a dance. The pair became partners, entering dance competitions for years, and are inseparable to this day. This was the milieu—convivial, energetic, and optimistic—that imprinted on his personality.

Upon moving away from Louisiana, Fred recalls, “For many years, I had no decided political views. Indeed, since I wasn’t a southern racist, I thought I must be a liberal.” It wasn’t until the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), where Fred soon joined and became an expert on recycling, waste reduction, and pollution taxes, that he saw firsthand the costs of government failure, a central tenet of the emerging study of public choice economics. From there he launched the career that produced the Competitive Enterprise Institute (CEI) in 1984 and the selections of this volume.

During the 1970s, he worked at the EPA and the Association of American Railroads. Regulatory economics became as much a calling card as his enthusiasm for finding, assimilating, and sharing ideas. Fred spoke quickly, thought more quickly, and engaged debate like an electric charge was forever running through his body—noticeable from the ever-present twinkle in his eye when he found an audience.

The first of 11 selections, “The Morality and Virtues of Capitalism and the Firm,” is part of a series of papers from CEI’s Center for Advancing Capitalism. The center is a project Fred established for his “third act,” for the work he wanted to do after passing on the formal leadership of the organization he had founded, built, and nurtured for three decades.

It is the only piece in this volume written while we were colleagues. He would do his thinking through conversation—in the hallway, working the phones, over lunch. Through numerous conversations and the editing process—which effectively left as much on the cutting room floor as it included—I watched Fred wrestle and clarify until he both understood the material and could communicate it clearly. The result is telling for how it places capitalism in context of both cultural features, like morality, and institutions like the modern firm.

The essay features mainstays of his thought, such as Leonard Read’s I, Pencil as a substitute for Hayek’s lessons on coordination and knowledge creation, Ronald Coase on the firm, Mary Douglas and Aaron Wildavsky on risk and communication models, Deirdre McCloskey on virtues, and, of course, the font of enlightenment for both moral and economic insight, Adam Smith. It may be the one, best place to start to understand the worldview and values of Fred Smith.

His writing is not homogeneous. The representative pieces here are long as well as short, written for newsletters and academic publications, and presented to popular audiences through magazines as well as to policy makers as expert testimony. If there is one through line, it is the emphasis on both the importance and the techniques of effective communication about ideas. The next three selections, “Are Corporations Suicidal,” “The Value of Communicating to Joe and Joan Citizen,” and “Countering the Assault on Capitalism,” illustrate this focus.

Through the years, Fred wrote scores of op-eds and essays to inform and persuade. In “The Progressive Era’s Derailment of Classical Liberal Evolution,” he explains the history of a set of ideas but more importantly, the implications. In policy discussions, one must consider the tradeoffs, including the difficult-to-see or hard-to-measure effects.

Writing about progressives’ penchant to create a “vast array of ‘promotional’ agencies—the Army Corps of Engineers, the Bureau of Land Management, the Rural Electrification Administration, the U.S. Forest Service—to dam rivers, build canals, manage timberlands, and string powerlines,” he takes the critical next step beyond description, explanation. Fred notes, “The pro-economic-growth biases of these institutions (undoubtedly the popular view at the time) led them to neglect environmental values.” And thus, economic growth became associated with low levels of environmental protection. Echoing the essence of free-market environmentalism, the essay makes a clarion call for a reinstitution of private property rights in environmental outcomes.

The next selection, “Sustainable Development—A Free-Market Perspective,” is a more fulsome treatment of free-market environmen- talism. Along with defense of the institutions of capitalism and values-based communication, developing an alternative to failing command-and-control environmental regulation was a hallmark of Fred’s career. His vision relies on property rights and market processes to enlist individuals everywhere in the fight to protect fragile ecological systems and species. Why rely on failing, resource-constrained political systems when an alternative that features individuals who could bring knowledge, resources, and self-interest to bear has a proven record of success?

“Autonomy,” written for Reason Magazine in 1990, celebrates individual liberty as much as it does mobility and the democratization of technology. A quick read, it is brimming with data on consumer habits, productivity, and manufacturing that are seamlessly married to anecdotes drawn from literature and history.

The next three selections—an excerpt from a book chapter, a study published in Regulation, and remarks to Congress—tackle risk, the nature of competition, and in a tightly argued statement, the risks created by inevitable government failures. In each case, an intellectual framework is presented, evidence is marshaled, and the conclusions are drawn clearly. Here we find Fred arguing against a naïve vision of safety, for institutions to deal with risk, and against the existence of antitrust laws that are routinely heralded as a means of consumer protection. With prescience, he warns lawmakers about a financial crisis before it unfolded from the moral hazard created by government interventions in the housing market.

The final selection is more illustrative of the joy and humor that Fred brought to his work and infused throughout CEI. More than anything, his enthusiasm is the most illustrative element of his legacy. In this essay, for Forbes, no less, he seeks to vindicate Charles Dickens’s unsympathetic capitalist, Ebenezer Scrooge. Ever mindful that wealth cannot be shared until it is created and that ultimately a dynamic society is a healthy society, what we think we know about a classic story is reinterpreted with humor and a healthy dose of economic thinking.

If there is a Holy Trinity in the gospels of Fred Smith, it may be the overlapping ideas of the moral dignity found in individual worth, the acknowledgement of powerful disruptions in life due to forces beyond individuals’ control, and the importance of clear, economic thinking about the reality of the world around us. Indeed, audiences familiar with Fred know to expect references to Adam Smith, Joseph Schumpeter, and Ronald Coase with regularity. Just as they know to expect a fresh perspective rooted in empiricism and presented with persuasion in mind. Invariably, his model for persuasion relies equally on the insights of political scientist Aaron Wildavsky and delivering a steady flow of ideas that hit you like a blast from a firehose.

Values-based communication is a talent. It is something to practice and treasure, like a gift from a dear friend. In Adam Smith’s most important work he observes:

Though our effectual good offices can very seldom be extended to any wider society than that of our own country, our good will is circumscribed by no boundary, but may embrace the immensity of the universe.

Smith. Extending to society. Goodwill. The immensity of the universe. These things fit together.

They are like the elements of every good story we know.

Kent Lassman Alexandria, Virginia December 26, 2020