Abstract

Around 9 % of the Lithuanian workforce emigrated to Western Europe after the enlargement of the European Union in 2004. I exploit this emigration wave to study the effect of emigration on wages in the sending country. Using household data from Lithuania and work permit and census data from the UK and Ireland, I demonstrate that emigration had a significant positive effect on the wages of stayers. A one-percentage-point increase in the emigration rate predicts a 0.67 % increase in real wages. This effect, however, is only statistically significant for men.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In a recent paper, Gagnon (2011) uses the emigration wave from Honduras after Hurricane Mitch and finds wage effects that are similar to those in this paper.

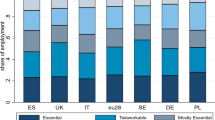

Own calculations from Eurostat.

Hungary and the Czech Republic, on the contrary, had outflows of less than 1 %.

The entire section on data is similar to Elsner (2011), which uses the same data sources.

For further information about PPS and NINo numbers, see http://www.welfare.ie and http://www.direct.gov.uk. In 2004 the UK introduced a Worker Registration Scheme (WRS) for workers from the new member states. Compared to the data from the WRS, NINo offers the advantage that it provides information on immigration before 2004. The WRS and NINo numbers after 2004 are similar.

Double counts are only possible if workers received a work permit in both destination countries. Although there does not seem to be any evidence of large numbers of workers registering in both countries, I am aware that double counting could lead to a downward bias in the estimates.

Other UK datasets, the Labour Force Survey and the European Community Household Panel have few observations on immigrants in each round, and they group immigrants from Eastern Europe by region, not by country.

\(\frac{\textrm{NINO}_{2003}}{\textrm{PPS}_{2002}}\) actually consists of two factors: \(\frac{\textrm{NINO}_{2003}}{\textrm{PPS}_{2003}}\), which accounts for the size of migrant flows to the UK relative to Ireland and \(\frac{\textrm{PPS}_{2003}}{\textrm{PPS}_{2002}}\), accounting for the change in migration flows to Ireland from 2002 to 2003. By multiplication of those two terms, PPS2003 cancels out.

The sampling weight p ghijt is the inverse probability that observation i is included in the sample.

Source: Statistics Lithuania.

Sources: statistical offices of the respective countries. For Denmark, the flows have been calculated from the difference in stocks. Tables can be produced upon request.

See the Online Appendix 1 for a detailed description of the educational tracks.

Between 2004 and 2006, Lithuania received EU structural funds of EUR 1.5 billion, which is 8 % of the country’s real GDP in 2004. The largest share of the funds, which were spread across 3,500 projects, went into infrastructure projects (European Commission 2007).

Figure 1 in the Online Appendix plots separate wage distributions for men and women. For men, there have been some changes to the left of the mean, but no substantial shifts in the probability mass. By contrast, for women the probability mass moved to the left of the mean, indicating a positive selection.

In 2004, minimum wages were EUR 7 in Ireland and GBP 4.85 in the UK.

Sources: Statistics Lithuania. Table available on request.

References

Aydemir A, Borjas G (2007) Cross-country variation in the impact of international migration: Canada, Mexico and the United States. J Eur Econ Assoc 5(4):663–708

Barrell R, FitzGerald J, Riley R (2010) EU enlargement and migration: assessing the macroeconomic impacts. J Common Mark Stud 48(2):373–395

Barrett A (2009) EU enlargement and Ireland’s labour market. In: Kahanec M, Zimmermann KF (eds) EU labor markets after post-enlargement migration. Springer, Berlin, pp 145–161. http://ftp.iza.org/dp4260.pdf

Bauer TK, Zimmermann KF (1999) Assessment of possible migration pressure and its labour market impact following EU enlargement to central and eastern Europe. IZA Research Report 3

Blanchflower DG, Shadforth C (2009) Fear, unemployment and migration. Econ J 119:136–182

Boeri T, Brücker H (2001) Eastern enlargement and EU-labour-markets. World Econ 2(1):49–68

Borjas GJ (2003) The labor demand curve is downward sloping: re-examining the impact of immigration on the labor market. Q J Econ 118(4):1335–1374

Bouton L, Paul S, Tiongson ER (2011) The impact of emigration on source country wages: evidence from the Republic of Moldova. Worldbank Policy Research Working Paper 5764

Brenke K, Yuksel M, Zimmermann KF (2009) Eu enlargement under continued mobility restrictions: consequences for the German labor market. In: Kahanec M, Zimmermann KF (eds) EU labor markets after post-enlargement migration. Springer, Berlin

Card D (2001) Immigrant inflows, native outflows and the labor market impact of higher immigration. J Labor Econ 19(1):22–64

Card D, Lemieux T (2001) Can falling supply explain the rising return to college for younger men? A cohort-based analysis. Q J Econ 116(2):705–46

Carrington WJ, Detragiache E, Vishwanath T (1996) Migration with endogenous moving costs. Am Econ Rev 86(4):909–930

Clemens MA (2011) Economics and emigration: trillion-dollar bills on the sidewalk? J Econom Perspect 25(3):83–106. doi:10.1257/jep.25.3.83

Constant AF (2012) Sizing it up: labor migration lessons of the EU enlargement to 27. In: Scribani international conference proceedings. Bruylant, Belgium, pp 49–77

Deutscher Bundestag (2004) Entwurf eines gesetzes über den arbeitsmarktzugang im rahmen der eu-erweiterung. Drucksache 15/2672

Drinkwater S, Eade J, Garapich M (2009) Poles apart? EU enlargement and the labour market outcomes of immigrants in the UK. Int Migr 47(1):161–190

Elsner B (2011) Emigration and wages: the EU enlargement experiment. IZA Discussion Paper 6111

European Commission (2007) The European structural funds (2004–2006). Lietuva

Friedberg RM (2001) The impact of mass migration on the Israeli labor market. Q J Econ 116(4):1373–1408

Friedberg RM, Hunt J (1995) The impact of immigration on host country wages, employment and growth. J Econom Perspect 9(2):23–44

Gagnon J (2011) “Stay with us?” The impact of emigration on wages in Honduras. OECD Working Paper 300

Hazans M, Philips K (2009) The post-enlargement migration experience in the Baltic labor markets. In: Kahanec M, Zimmermann KF (eds) EU labor markets after post-enlargement migration. Springer, Berlin, pp 255–304

Home Office (2009) Accession monitoring report, May 2004–December 2008, a8 countries. Home Office Report

Kaczmarczyk P, Mioduszewska M, Zylicz A (2009) Impact of the post-accession migration on the Polish labor market. In: Kahanec M, Zimmermann KF (eds) EU labor markets after post-enlargement migration. Springer, Berlin, pp 219–253

Kahanec M, Zimmermann KF (eds) (2009) EU labor markets after post-enlargement migration. Springer, Berlin

Kahanec M, Zaiceva A, Zimmermann KF (2009) Lessons from migration after EU enlargement. In: Kahanec M, Zimmermann KF (eds) EU labor markets after post-enlargement migration. Springer, Berlin, pp 3–45

Kerr SP, Kerr WR (2011) Economic impacts of immigration: a survey. Finnish Econ Pap 24(1):1–32. http://www.nber.org/papers/w16736.pdf

Longhi S, Nijkamp P, Poot J (2010) Joint impacts of immigration on wages and employment: review and meta-analysis. J Geogr Syst 12:355–387. doi:10.1007/s10109-010-0111-y

McKenzie D, Rapoport H (2010) Self-selection patterns in Mexico–US migration: the role of migration networks. Rev Econ Stat 92(4):811–821

Mishra P (2007) Emigration and wages in source countries: evidence from Mexico. J Dev Econ 82:180–199

Saleheen J, Shadforth C (2006) The economic characteristics of immigrants and their impact on supply. Bank of Engl Q Bull Q4:373–385

Sinn HW (2004) Eu enlargement, migration, and the new constitution. CESifo Working Paper 1367

Solow RM (1956) A contribution to the theory of economic growth. Q J Econ 70(1):65–94. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1884513

Wadensjö E (2007) Migration to Sweden from the new EU member states. IZA Discussion Paper 3190

Zaiceva A, Zimmermann KF (2008) Scale, diversity and determinants of labour migration in Europe. Oxf Rev Econ Policy 24(3):428–452. doi:10.1093/oxrep/grn028

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Gaia Narciso for all her support and encouragement. I would also like to thank the editor, three anonymous referees, Catia Batista, Karol Borowiecki, John FitzGerald, Ulrich Gunter, Julia Anna Matz, Corina Miller, Mrdjan Mladjan, Alfredo Paloyo, Todd Sorensen, Pedro Vicente, and Michael Wycherley, as well as the seminar participants at the 6th ISNE conference in Limerick/IE, the 3rd RGS doctoral conference in Bochum/GER, the 24th Irish Economic Association annual conference in Belfast/UK, and the TCD Development Working Group for helpful comments. The Lithuanian and Irish Statistical Offices were very helpful in providing the data. The author gratefully acknowledges funding from the Irish Research Council for the Humanities & Social Sciences and the Department of Economics at Trinity College Dublin. The paper has been accepted before the author took up a research position at IZA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Klaus F. Zimmermann

Electronic Supplementary Material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Elsner, B. Does emigration benefit the stayers? Evidence from EU enlargement. J Popul Econ 26, 531–553 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-012-0452-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-012-0452-6