Abstract

This paper studies the effects of immigration on the allocation of occupational physical burden and work injury risks. Using data for England and Wales from the Labour Force Survey (2003–2013), we find that, on average, immigration leads to a reallocation of UK-born workers towards jobs characterised by lower physical burden and injury risk. The results also show important differences across skill groups. Immigration reduces the average physical burden of UK-born workers with medium levels of education, but has no significant effect on those with low levels. We also find that that immigration led to an improvement self-reported measures of native workers’ health. These findings, together with the evidence that immigrants report lower injury rates than natives, suggest that the reallocation of tasks could reduce overall health care costs and the human and financial costs typically associated with workplace injuries.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

There is a large literature exploring the impacts of immigration on different factors such as labour markets, public finances, delivery of public services, housing market and criminality, among others (Dustmann et al. 2013; Dustmann et al. 2010; Dustmann and Frattini 2014; Sá 2015; Bell et al. 2013; Giuntella et al. 2018). However, there is less evidence about the impact of immigration on health care costs. This is an important gap in the evidence as immigrants are often blamed for high levels of health care expenditure in host countries, particularly in countries that have publicly funded health care systems (Giuntella et al. 2018). The existing evidence has mainly focused on exploring the health trajectories of immigrants and suggests that immigrants are often healthier upon arrival in the host country but that their health outcomes converge to those of natives over time (Kennedy et al. 2015). However, just a few studies have explored the impact of immigration on the health outcomes of natives (Giuntella and Mazzonna 2015), a major factor in the determination of the overall impact of immigration on health care expenditure.

The classical model of labor demand and supply suggests that immigration has a negative effect on the wages and employment of the residents of the host country (Borjas 2014). However, most studies have found little empirical support for this effect. Previous research suggests that this lack of evidence could be explained by differences in comparative advantage between immigrant and native workers. Immigrants have a comparative advantage in manual-intensive jobs, while native workers have an advantage in communication-intensive jobs due to better language skills. An expansion in the supply of immigrants increases the relative returns to communication-intensive jobs pushing native workers towards those jobs (Peri 2012, 2016; D’Amuri and Peri 2014; Ottaviano et al. 2013; Peri and Sparber 2009).

This paper contributes to this literature by exploring if these labor market adjustments lead to a reallocation of natives’ occupational physical burden (e.g. lifting and carrying heavy loads) and occupational health risks (i.e. injury risk) to immigrants. While previous studies analysed the effects of immigration on task-complexity, in this study, we separately identify the effect of immigration on the likelihood to engage in risky jobs. We also document that while tax complexity is highly correlated with job physical intensity and occupational risk, there is no perfect correspondence. Furthermore, previous studies focused primarily on the effects of low-skilled immigration on low-skilled workers. However, as shown by Dustmann et al. (2013), immigrants, and in particular recent immigrants, in the UK are well educated but downgrade substantially upon arrival, accepting jobs far below the ones accepted by natives with a comparable educational background. To account for the peculiarity of the UK context, we test the heterogeneous effects of immigration on work-related health risks along the skill distribution.

In order to provide this evidence, we use 2003–2013 data for England and Wales for the analysis. The consequences of immigration are at the centre of the political discussion in the UK and analysis suggests that immigration was one of the key drivers of the British vote to leave the European Union (EU) (Vargas-Silva 2016). According to the 2011 Census, there were 7.5 million foreign-born persons living in England and Wales, corresponding to 13.4% of the population. Close to 40% of these immigrants arrived from 2004 onwards and, many of them are citizens of the new EU member states who found jobs in the low-wage sector (Drinkwater et al. 2009). There is widespread geographic dispersion on the level and change in immigration (Fig. 1). In fact, in 2011, immigrants represented over 10% of the population in a quarter of local authorities in England and Wales.

The increase in immigration to the UK over the last decade has been accompanied by a decrease in UK-born workers’ average physical burden and injury rates (Fig. 2) and share of high-physically demanding jobs held by UK-born workers (Fig. 3). This paper explores the connection between these trends.

We exploit spatial and temporal variation in the share of immigrants residing across local authorities. To address the concern that immigration may be endogenous to labor market demand and correlated with unobserved determinants of working conditions and work health risks, we used an instrumental variable approach exploiting the correlation between immigrant inflows and historical concentration of immigrants across local authorities in England and Wales (Bell et al. 2013; Sá 2015). Furthermore, using retrospective information on worker’s occupational characteristics, we analyse the effects of immigration on occupational changes at the individual level. Examining individual labor market transitions allows controlling for individual time-invariant characteristics. This exercise strengthens the causal interpretation of our results mitigating the concern that our identification strategy may be confounded by spillover effects and internal mobility (Borjas et al. 1996; Borjas 2003).

Our results suggest that immigration pushes UK-born workers towards jobs characterised by lower physical burden and injury risk. The effects are particularly large for UK-born males with medium levels of education holding physically demanding jobs. These workers have lower search and training costs for new jobs and can take advantage of the increased demand for communication-intensive jobs induced by the inflow of immigrants. Consistent with these findings, immigration also reduces the average occupational risk for natives with medium levels of education. We also find that that immigration reduced natives’ likelihood to report work-related disability and any health problem. The reallocation of tasks, together with the evidence that immigrants report lower injury rates than natives, suggests that immigration reduces health care, productivity and financial costs associated with work-related injuries in the UK.Footnote 1

This paper is organised as follows. Section 2 provides the theoretical intuition behind the analysis. Section 3 provides a discussion of the data, the empirical specification and the identification strategy. Section 4 presents the main results of the paper. Section 5 presents the robustness checks. Concluding remarks are given in Section 6.

2 Theoretical framework

Our theoretical intuition is based on three potential differences between immigrants and natives: risk aversion, health capital and estimation of risk. We assume that there is a trade-off between wages in a given occupation and the level of physical burden/occupational risk. Workers dislike physical burden and risk and require a higher compensation in order to work in physically intensive/risky occupations (i.e. compensating wage premium). The wage-risk/burden trade-offs do not need to be equal across workers. If workers have different degrees of risk aversion, those who are less risk-averse are more likely to self-select into riskier occupations (Orrenius and Zavodny 2012). Immigrant status is likely to be strongly linked with risk-aversion levels. There is substantial empirical evidence suggesting that immigrants tend to be less risk averse than those who stay behind (Dustmann et al. 2017) and it is possible that, on average, they are also less risk averse than host country residents. This could be particularly the case for occupational risk as many immigrants come from countries in which occupational risk is much higher (Orrenius and Zavodny 2012).

Also, there is abundant evidence which suggests that immigrants have greater health capital than natives (Antecol and Bedard 2006; Kennedy et al. 2015; Giuntella 2017), a factor that suggests that they also have a comparative advantage in jobs with a higher physical burden/higher injury risk. This will, in turn, encourage immigrants to self-select into more physically intensive/risky jobs.

It is also possible that immigrants are simply more likely to underestimate occupational risk than natives (Dávila et al. 2011). This could occur because of a lack of familiarity with the host country or because employers intentionally mislead immigrants about it. Employers may be more able to mislead immigrants who are less proficient in the host country language and are recent arrivals (Orrenius and Zavodny 2012).

These three potential differences between immigrants and natives will make immigrants self-select into jobs with greater physical burden/occupational risk. Immigrants will do those jobs for a lower compensation and could displace native workers to less physically intensive and less risky jobs in which they have a relative advantage. In the empirical section, we explore this link between immigration and the physical burden/occupational risk of natives. We also expect that those native workers who are overqualified for physically intensive/risky jobs and who have lower retraining costs are more likely to adjust to the presence of immigrants. As such, we expect the main impact to be on workers who are overqualified for the physically intensive/risky jobs they held. We also explore this empirically by looking at the job changes of natives in response to immigration by skill groups. While most of the immigrants to the UK are well educated, they tend to be overqualified for their jobs accepting occupations that are well below occupations accepted by natives with similar educational background. Low-skilled natives may therefore be more exposed to competition with overqualified immigrants employed in low-skilled jobs, while high-skilled natives may extract most of the general positive equilibrium effects induced by immigration (Dustmann et al. 2008, 2013).Footnote 2

It is important to highlight that more manual work is likely to involve a higher physical burden and injury risk. Previous studies suggest that immigrants have a comparative advantage in manual-intensive jobs, while native workers have an advantage in communication-intensive jobs due to better language skills and that an expansion in the supply of immigrant workers increases the relative returns to communication-intensive jobs pushing native workers towards those jobs (Peri 2012, 2016; D’Amuri and Peri 2014; Ottaviano et al. 2013; Peri and Sparber 2009). We would expect an overall positive correlation between the manual content of a job and its risk of injury/physical burden. This could be one of the channels by which immigration leads to a reallocation of work risk from natives to immigrants. However, this correlation is not one to one. Two similar jobs in terms of their manual content can have very different physical burden and different injury rates. Among the jobs having a very high physical intensity (highest quartile of physical burden index), only 43% are in the highest quartile of the manual index. For instance, photographers or bus drivers are classified as workers in manually intensive jobs, but their physical burden is below the median in our sample of occupations. Furthermore, there is also no one to one matching between manual jobs and jobs with a higher risk of injury. Similarly, the injury rate risk of medical doctors is among the lowest across occupations, while that of veterinarians, an occupation with a similar manual content, is among the highest.Footnote 3

3 Data and empirical specification

3.1 Data

The main dataset is the special license version of the UK Labour Force Survey (LFS) from 2003 to 2013. The special license version of the LFS is only available since 2003. The sample is limited to employed individuals between 20 and 59 years of age. The information on country of birth and location is used to construct an indicator of the immigrant (i.e. foreign-born) share of the population by local authority.

The ISCO-88 classification and the General Index for Job Demands in Occupations constructed by Kroll (2011) is used to create a variable (1 to 10 metric) for the average physical burden of a given job. The factors determining the physical burden of a job include considerations such as having to lift and/or carry heavy loads, bend, kneel or lie down, working in the presence of smoke, dust, gases, vapours, working in cold, heat, or wet conditions, etc. We also created two indicators for jobs with high physical burden (above median) and very high physical burden (highest quartile). Workers are also classified according to occupations (1-digit) and blue- and white-collar status following standard OECD classifications.

The special license of the LFS is combined with the standard version to measure work-related risks. There is no information on work-related injuries in the special license of the LFS.Footnote 4 This information is available in the standard version, but this version does not include information on the individual’s local authority of residence. In order to analyse the relation between immigration and actual injury rates, we constructed a time-varying index of occupational risk based on injury rates by occupation and year. Injury rates are calculated as the share of individuals in a given occupation which reported accidents resulting in injury at work or in the course of work in the last 12 months. Those occupations with an injury rate above the median are categorised as risky. Examples of occupations with high/low physical burden and injury rate are reported in Table 12.

We also explore the impact of immigration on natives with different levels of education. Natives are divided in three educational groups. The “high education” group refers to those with a university degree or equivalent. The “medium education” group refers to those with a high school degree or equivalent, including GCE, A-level and GCSE grades A* to C. Finally, the “low education” category refers to those natives with no qualifications or qualifications below the ones included in other categories.

Descriptive statistics for the outcomes and covariates are reported in Table 1. On average, immigrants are more likely to work in jobs with a higher physical burden, but the injury rate is similar across the two groups. Immigrants are also younger than natives and more likely to be concentrated in the higher or lower educational groups.

We also present evidence exploiting retrospective information on worker’s occupational characteristics. Since 2003, the first quarter of the standard LFS collects information on respondents’ occupation in the previous year. This allows us to analyse the effects of immigration on occupational changes at the individual level. By removing any individual time invariant characteristics and following the worker wherever he/she moves, we can address the concern about the potential spillovers on other labor markets due to spatial arbitrage (Borjas 2003).

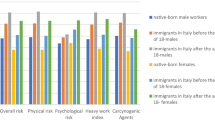

Table 2 reports immigrant-native differences in the likelihood of working in physically intensive jobs (1 to 10 metric) by gender. All estimates include standard demographic controls (a quartic in age, marital status and number of children), year and local authority fixed effects. Previous studies suggest that as immigrants are often positively selected on health, they have incentives to self-select into more strenuous jobs (Giuntella and Mazzonna 2015) and are more likely to hold risky jobs (Orrenius and Zavodny 2012). The estimates in Table 2 support this dynamic. Immigrants are significantly more likely to hold jobs characterised by higher physical burden (column 1). With respect to the mean, immigrants are 11% more likely to hold jobs in the upper quartile of the physical burden index distribution (physical burden> 7, see column 3). The coefficients are smaller, but the differences remain significant when controlling for socio-demographic characteristics (columns 2 and 4). With respect to the mean, immigrants are 5% more likely to hold high physical burden jobs than natives with similar characteristics.

The native-immigrant difference is also present for women. With respect to the mean of the dependent variable, foreign-born women are 53% more likely to be employed in physically high-intensive occupations. However, it is worth noting that in general, women are less likely to work in physically demanding jobs (only 12% of native women work in physically high-demanding jobs vs. 30% of native men). For this reason, in our analysis, we focus primarily on native men.

Table 3 shows differences in occupational risk and individual likelihood of experiencing an injury between natives and immigrants. The sample is smaller as the information on occupational injury rate is not available for all the occupations in every year.Footnote 5 In the first two columns, we estimate the native-immigrant difference in occupational risk (continuous variable and above median indicator). Given the higher share of immigrants in physical demanding jobs (see Table 1), it is unsurprising that we find that immigrants are 10% more likely to work in occupations with a higher injury risk (column 2). At the same time, using information on self-reported injuries, we show that immigrants are 5% less likely to report an injury (column 3) and that this result holds when we compare immigrants and natives in the same occupational category (column 4). It is possible that immigrants are less likely to officially report injuries compared to natives (Orrenius and Zavodny 2012). However, we employ self-reported data and this could mitigate this bias. A possible explanation for the lower injury rates observed by immigrants in a given occupational category is that immigrants are typically healthier than natives (Giuntella et al. 2018) and the ability to cope with physical stress and risk is a function of health capital.

3.2 Empirical specification

To identify the effect of immigration on job physical burden and occupational risk, we exploit variation over time in the share of immigrants living in each local authority between 2003 and 2013. The estimated empirical model is as follows:

where Yilt is a metric of job physical burden or occupational risk of individual i, in local authority l at time t; Slt is the share of immigrants in local authority l at time t; Xilt is a vector of individual characteristics; Zlt is a vector of time-varying characteristics at the local authority level (share of White, Asian and Black population, share of individuals with low, medium and high education, share of female population, log of average gross income, local authority employment rate and share of individuals claiming unemployment benefits) and μl and ηt are local authority and year fixed effects, respectively; and 𝜖ilt captures the residual variation.

Immigrants might endogenously cluster in areas with better economic conditions and have an impact on natives’ internal mobility (e.g., Borjas et al. 1996, Borjas2003). We adopt the traditional “shift share” instrumental variable approach (Altonji and Card 1991; Card 2001; Bell et al. 2013; Sá 2015) to address this endogeneity. This approach exploits the fact that immigrants tend to locate in areas with higher densities of individuals from their same country of origin.

The annual national inflow of immigrants from each country across local authorities is distributed according to the concentration of foreign-born individuals in the 1991 UK Census, reducing the bias from endogeneity.

We define Fct as the total population of immigrants from country c residing in England and Wales in year t and scl1991 as the share of that population residing in local authority l in the year 1991. We then construct \(\hat {F}_{clt}\), the imputed population from country c in local authority l in year t, as follows:

and the imputed total share of immigrants \(\hat {S}_{lt}\) in local authority l in year t will be

where Pl,1991 is the total population in local authority l in 1991. Thus, the predicted number of new immigrants from a given country c in year t in local authority l is obtained by redistributing the national inflow of immigrants from country c based on the distribution of immigrants across local authorities in 1991. Adding data for all countries of origin, it is possible to obtain a measure of the predicted total immigrant inflow in each local authority and use it as an instrument for the actual share of immigrants. We consider nine foreign regions of origin: Africa, Americas and Caribbean, Bangladesh and Pakistan, India, Ireland, EU-15, Poland and other countries.

One potential threat to the validity of this approach is that the instrument cannot credibly address the resulting endogeneity problem if the local economic shocks that attracted immigrants persist over time. However, this problem is substantially mitigated by including local authority fixed effects and by controlling for time-varying characteristics at the local authority level. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that past levels of concentration of immigrants are not correlated with current unobserved local shocks that might be correlated with a job’s level of physical burden and occupational risk. In other words, the exclusion restriction holds under the assumption that—after controlling for local authority and year fixed effects, and local authority time-varying characteristics—the imputed inflow of immigrants is orthogonal to the local specific shocks and trends in labor market conditions.

We test the robustness of our results to a change in the geographical unit using a higher level of aggregation to address the concern that our results may be biased by the effects of immigration on native internal mobility (Borjas et al. 1996). We also show that our results are robust to the inclusion of local authority specific time trends. Finally, a placebo test is conducted to analyse the effects of immigration on past trends in physical burden associated with a given occupation and injury risk and find there is no evidence of significant correlations.

4 Main results

4.1 Physical burden

Table 4 reports on the relationship between immigration and the physical burden associated with a given occupation. In Panel A, we restrict the analysis to UK-born male workers. The OLS estimates show that there is a negative association between the share of immigrants living in a local authority and average physical burden. A 10 percentage point increase in the share of immigrants in a local authority (one standard deviation) is associated with a 0.10 points decrease in average physical burden of native males (column 1, OLS). 2SLS estimates are larger than the OLS ones suggesting that immigrants tend to locate in areas where occupations are characterised by a higher physical burden.Footnote 6 A 10 percentage point increase in the share of immigrants in a local authority (one standard deviation) reduces the average physical burden of native males by 0.25 points (column 2), which corresponds to a 0.09 standard deviation. This is a reduction of 5% with respect to the mean of the dependent variable. These effects are larger when we focus on the likelihood of being employed in a highly physically intensive job. A 10 percentage point increase in share of immigrants reduces the likelihood of male natives to work in a job in the upper quartile of the physical burden distribution by a 15% effect with respect to the mean (column 4).

The effects are smaller when focusing on women (Panel B). A 10 percentage point increase in the share of immigrants in a local authority (one standard deviation) reduces the average physical burden of native females by 0.13 points (column 2), which corresponds to a 0.06 standard deviation. Again, these results are not surprising given the low number of native women working in these jobs. For this reason, henceforth, we focus on the results on the sample of UK-born men, but we report results for UK-born women in the Appendix. Our main results are robust to the inclusion of a local authority specific quadratic time trend and the inclusion of sectoral employment shares (Table 15). Furthermore, we show that including the manual-intensity index used in previous studies (Peri and Sparber 2009) accounts for less than a third of the overall effect (see columns 3 and 6 of Table 15).

Table 5 shows that the effects are largely concentrated among men with medium levels of education.Footnote 7

For male native workers with a medium level of education, a 10 percentage point increase in the share of immigrants (one standard deviation) would lead to a 0.14 standard deviation reduction in physical burden (column 3).

We also find some evidence of a reduction in physical burden (0.06 standard deviations) for men with high levels of education (column 2). On the other hand, there is no effect for those with low levels of education.

These results indicate that immigration reduces the physical burden of those with a medium level of education who may be overqualified for a physically intensive job. Individuals with low re-training costs are those who are more likely to be pushed towards less physically intensive jobs as a response to immigration (Orrenius and Zavodny 2010). These results are consistent with the heterogeneous effects observed by previous studies analysing the effects of immigration on UK-born wages (Dustmann et al. 2008).

This intuition is confirmed by the evidence reported in Table 6, which considers information on previous year occupation (available for the second quarter of each year in the LFS). In this Table, we compare occupation one year ago with current occupation and determined whether the current job has a higher or lower physical burden.Footnote 8 Panel A examines the effect of immigration on the likelihood that a native man will switch to a less physically intensive job. As expected, there is a large and statistically significant effect among individuals with medium levels of education previously working in blue collar jobs (column 5). A 10 percentage point increase in the share of immigrants increases the likelihood of moving to an occupation with lower physical burden by a 0.1 standard deviation (approximately, a 30% effect with respect to the mean). On the contrary, the same change in the immigrant share would reduce the likelihood of moving to a less physically intensive job by a 0.09 standard deviation (a 40% reduction with respect to the mean of the dependent variable) for those with low levels of education. Panel B reports similar effects when we use the absolute change in the physical burden measure between the previous and current year as the dependent variable.

4.2 Occupational risk

We now turn to investigate whether the reallocation of physical burden induced by immigration affects occupational risk. Table 7 shows that an increase in the share of immigrants living in a local authority is associated with a reduction in the likelihood of being employed in a riskier occupation. A 10 percentage point increase in the share of immigrants is associated with a 0.5 standard deviation reduction in the likelihood of native men working in an occupation with an injury rate higher than the median (a 40% effect with respect to the sample mean). Again, the effect is only significant for those with medium levels of education.Footnote 9 Table 16 shows that results hold to the inclusion of a local authority specific quadratic time trend (Panel A) and sectoral employment shares (Panel B). Furthermore, controlling for the occupational task-complexity accounts for approximately a third of the baseline effect, yet the coefficient is still statistically and economically significant (Panel C).

4.3 Effects on self-reported health measures

Next, we investigate whether immigration had effects on the health of natives. The LFS includes information on self-reported disability and any health-related problem. However, there are several problems with the use of these metrics over our period of interest as the health questions where changed in 2009 and 2013.Footnote 10 While we harmonised the data, these metrics are likely to suffer from substantial measurement error as well as self-reporting bias. Nevertheless, the results shown in Table 8 parallel the analysis examining physical intensity and occupational risk. A 10 percentage point increase in the share of immigrants is associated with a 10% reduction in the likelihood of native men reporting any work-related disability with respect to the average in the sample (Panel A) and a 3% reduction in the likelihood of reporting any health issue (Panel B). The effects are concentrated among those with medium and high levels of education. Estimates are less precise when analysing self-reported health problems but tend in the same direction.

4.4 Welfare implications

The Health and Safety Executive (HSE) statistics suggest that there were approximately 629,000 non-fatal injuries in the UK during 2014–2015. The HSE estimate the average cost of a non-fatal injury to be around GBP 7,500.Footnote 11 Immigration reduced the average physical burden and injury risk among UK-born workers and immigrants exhibit a lower likelihood of reporting any injury in a given occupation (see Table 3). These two factors suggest that immigration could lead to a reduction in the overall injury rate.

Another key aspect for the welfare implication of our result is the change in working conditions of immigrants with respect to the pre-migration situation. Is there a Pareto-improvement? It is possible for immigrants to have lower injury rates in the UK than in their home countries, even if they work at riskier jobs than UK natives. This would imply an improvement in welfare for both natives and immigrants as a result of immigration. To gauge whether this is the case, we use the 2007 European Labour Force Survey which contains the work-related Accidents, Health Problems and Hazardous Exposure ad hoc module. We compare the likelihood of reporting non-fatal injuries in the UK and in several new Eastern European EU member states which represented the main key countries of immigration to the UK in the period under study.Footnote 12 As shown in Table 9, we find that the likelihood of reporting any injury is lower in the UK (− 60% with respect to the mean) than in the new EU member states (column 1). This difference remains significant (− 20% with respect to the mean) when including occupation fixed effects (see column 2). In columns 3 and 4, we focus on the differences in the likelihood of injuries between the UK and Poland which is by far the major country of origin of immigrants for the period considered in the paper (Rienzo and Vargas-Silva 2012). This suggests that immigration could lead to “pareto-improvement” in working conditions.

5 Robustness checks

To address the concern that results may be biased by the effects of immigration on internal native mobility, we check the robustness of our results to changing the geographical unit of analysis to UK regions.Footnote 13 The coefficients on physical burden (column 2, Table 10) remain substantially unchanged compared to the local authority units (columns 1 and 3). Note that all the estimates include socio-demographic controls and year fixed effects.Footnote 14

In Table 11, we conduct a placebo test to check if the results are driven by pre-existing trends affecting immigration and occupational physical burden and injury risk. As in Foged and Peri (2016), we explore whether the 2004–2013 change in the instrument (the predicted change in the share of immigrants) is correlated across local authorities with the pre-treatment trends in physical burden and the occupational injury rate. More specifically, using data from the 1991 UK Census, we compute the average job physical burden by local authority as of 1991. The predicted change in the share of immigrants across local authorities between 2004 and 2013 is regressed on changes in our outcomes of interest between 1991 and 2003. As there is no information on occupational injuries for 1991, the analysis is repeated for occupational injury risk analysing the difference in occupational injury rates between 2003 and 2004. All estimates include controls for average age, and share of individuals with high and medium education.

Column 1 shows no significant relationship between future immigration inflows and pre-existing trends in physical burden. Similarly, columns 2 and 3 report results from regressions of the change in the share of immigrants across local authorities between 2004 and 2013 on changes in physical burden and the occupational injury rate between 2003 and 2004. Again, there is no significant relationship between the change in immigration observed between 2004 and 2013 and pre-trends in our outcomes of interest. Overall, these results provide support to a causal interpretation of our main results.

Finally, since the burden associated with each occupation might be multidimensional, we also consider the psycho-social burden of a given job (Kroll 2011). However, the results reported in Table 20 show that there is no evidence of significant effects on psychological burden.

6 Conclusions

This article contributes to the literature on the labor market effects of immigration by estimating its impact on the physical burden and work-related health risk of UK-born workers in England and Wales from 2003 to 2013. The results suggest that immigration reduces the average physical burden of native workers. We also find that that immigration led to an improvement of self-reported health measures of native workers’ health. However, the mean effects mask important differences along the skill distribution. Immigration significantly reduces the average physical burden of native workers with high or medium levels of education and has no significant impact on those with low levels of education.

Our results are consistent with the existence of imperfect substitution between immigrant and native workers and the observation that immigrants have a comparative advantage in self-selecting into more strenuous jobs. The inflow of workers with a comparative advantage in manual tasks increases the demand for and returns to communication-intensive ones. This increase in returns leads individuals with low re-training costs (medium- and high-skilled) towards jobs that are less physically intensive and involve lower injury risks.

These findings, together with the evidence that immigrants exhibit lower injury rates than natives, suggest that the reallocation of tasks may result in fewer total injuries and lower health care and productivity costs of workplace injuries.

Notes

A recent report from the UK Health and Safety Executive suggests that health care costs are only a small proportion of the overall costs associated with work-related injuries. See http://www.hse.gov.uk/statistics/pdf/cost-to-britain.pdf

Lewis (2011) shows that immigrant inflows may reduce incentives to adopt new technologies and labor-saving processes delaying the transition to less manual-intensive health-hazardous jobs. Yet, there is less evidence of this type of adjustment for the case of the UK.

See Table 12 for further details.

There is no firm level information on work-related injuries in the UK, publicly available.

Results on physical burden hold also in the restricted sample.

This difference between OLS and 2SLS tends in the same direction for all estimates reported in the main text (see Appendix).

The heterogeneity of results by educational groups is consistent with recent findings on the effects of immigration on wages showing that the impact of immigration can be different along the wage distribution (Dustmann et al. 2013). Consistent with previous literature, we find no evidence of significant effects on wages (Table 17) nor any evidence of significant effects on employment and labor market participation (Table 18). While not precisely estimated, the coefficient on wages is negative and (larger) in absolute value when focusing on the low-skilled who are more likely to suffer immigrant competition.

Note that those who leave employment are not in the sample and this could lead to some selection issues.

Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia.

The LFS contains information on region of usual residence. England and Wales are divided into 17 regions: Tine and Wear, South West, Rest of Northern Region, West Midlands (Metropolitan), South York Shire, Rest of West Midlands, West Yorkshire, Greater Manchester, Rest of Yorkshire and Humberside, Merseyside, East Midlands, Rest of North West, East Anglia and Wales.

The regional estimations do not include regional fixed effects as there is not enough variation when using both year and regional fixed effects.

References

Altonji JG, Card D (1991) The effects of immigration on the labor market outcomes of less-skilled natives. In: Immigration, trade and the labor market. University of Chicago Press, pp 201–234

Antecol H, Bedard K (2006) Unhealthy assimilation: why do immigrants converge to American health status levels? Demography 43(2):337–360

Bell B, Fasani F, Machin S (2013) Crime and immigration: evidence from large immigrant waves. Rev Econ Stat 21(3):1278–1290

Borjas GJ (2003) The labor demand curve is downward sloping: reexamining the impact of immigration on the labor market. Q J Econ 118(4):1335–1374

Borjas GJ (2014) Immigration economics. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Borjas GJ, Freeman RB, Katz LF (1996) Searching for the effect of immigration on the labor market. Am Econ Rev Pap Proc 86(2):246–251

Card D (2001) Immigrant inflows, native outflows, and the local labor market impacts of higher immigration. J Labor Econ 19(1):22–64

D’Amuri F, Peri G (2014) Immigration, jobs, and employment protection: evidence from europe before and during the great recession. J Eur Econ Assoc 12 (2):432–464

Dávila A, Mora MT, González R (2011) English-language proficiency and occupational risk among Hispanic immigrant men in the United States. Ind Relat: J Econ Soc 50(2):263–296

Drinkwater S, Eade J, Garapich M (2009) Poles apart? EU enlargement and the labour market outcomes of immigrants in the United Kingdom. Int Migr 47 (1):161–190

Dustmann C, Frattini T (2014) The fiscal effects of immigration to the UK. Econ J 124(580):F593–F643. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12181

Dustmann C, Glitz A, Frattini T (2008) The labour market impact of immigration. Oxf Rev Econ Policy 24(3):477–494

Dustmann C, Frattini T, Halls C (2010) Assessing the fiscal costs and benefits of A8 migration to the UK. Fisc Stud 31(1):1–41

Dustmann C, Frattini T, Preston IP (2013) The effect of immigration along the distribution of wages. Rev Econ Stud 80(1):145–173

Dustmann C, Fasani F, Meng X, Minale L et al (2017) Risk attitudes and household migration decisions. Tech. rep.

Foged M, Peri G (2016) Immigrants’ effect on native workers: new analysis on longitudinal data. Am Econ J: Appl Econ 8(2):1–34

Giuntella O (2017) Why does the health of immigrants deteriorate? Evidence from birth records. J Health Econ 54:1–16

Giuntella O, Mazzonna F (2015) Do immigrants improve the health of natives? J Health Econ 43:140–153

Giuntella O, Nicodemo C, Vargas-Silva C (2018) The effects of immigration on waiting times. J Health Econ

Kennedy S, Kidd MP, McDonald JT, Biddle N (2015) The healthy immigrant effect: patterns and evidence from four countries. J Int Migr Integr 16 (2):317–332

Kroll LE (2011) Construction and validation of a general index for job demands in occupations based on ISCO-88 and KldB-92. Methoden Daten Anal 5(63–90)

Lewis E (2011) Immigration, skill mix, and capital skill complementarity. Q J Econ 126(2):1029–1069

Orrenius PM, Zavodny M (2010) Mexican immigrant employment outcomes over the business cycle. Am Econ Rev 100(2):316–320

Orrenius PM, Zavodny M (2012) Immigrants in risky occupations. IZA Discussion Paper 6693

Ottaviano GI, Peri G, Wright GC (2013) Immigration, offshoring, and American jobs. Am Econ Rev 103(5):1925–1959

Peri G (2012) The effect of immigration on productivity: evidence from US states. Rev Econ Stat 94(1):348–358

Peri G (2016) Immigrants, productivity, and labor markets. J Econ Perspect 30(4):3–30

Peri G, Sparber C (2009) Task specialization, immigration, and wages. Am Econ J: Appl Econ 1(3):135–169

Rienzo C, Vargas-Silva C (2012) Migrants in the UK: an overview. Migration Observatory Briefing. COMPAS, University of Oxford, Oxford

Sá F (2015) Immigration and house prices in the UK. Econ J 125(587):1393–1424

Vargas-Silva C (2016) EU migration to and from the UK after Brexit. Intereconomics 51(5):251–255

Acknowledgments

This paper benefited from discussion with Esther Arroyo, Francesco Fasani, Judit Vall-Castello, David Slusky and Raphael Wittenberg. We thank participants to seminars at Universitat Pompeu Fabra, University of Oxford, American Society of Health Economics (2015), XIII IZA Annual Migration Conference. We are grateful to three anonymous referees for their help and guidance. We thank Andreea Antuca for precious research assistance. The scoping research for this paper was funded by the John Fell Oxford University Press (OUP) Research Fund and the main research was funded by the European Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 727072 (REMINDER Project).

Funding

This study has received funding from the European Union, Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 727072.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Carlos Vargas-Silva has received research funds from the European Commission, Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 727072. The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Responsible editor: Klaus F. Zimmermann

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Giuntella, O., Mazzonna, F., Nicodemo, C. et al. Immigration and the reallocation of work health risks. J Popul Econ 32, 1009–1042 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-018-0710-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-018-0710-3