Florian Röhrbein (centre) is managing director of the Neurorobotics project under the Human Brain Project at Technical University of Munich, which is developing simulated and real systems to reconstruct the human brain.Credit: Andreas Heddergott/TUM

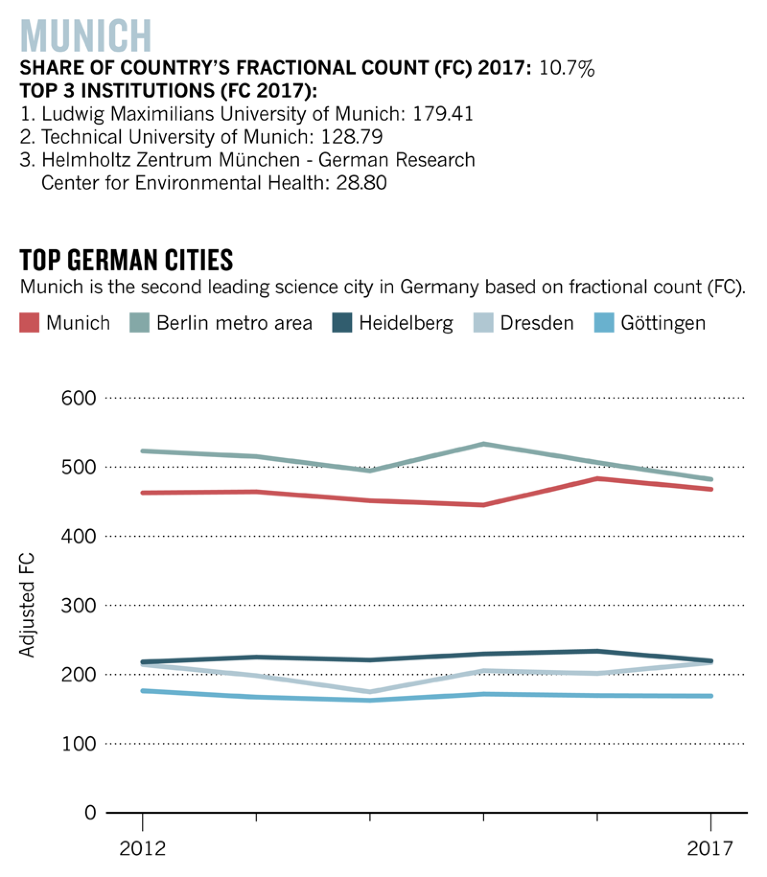

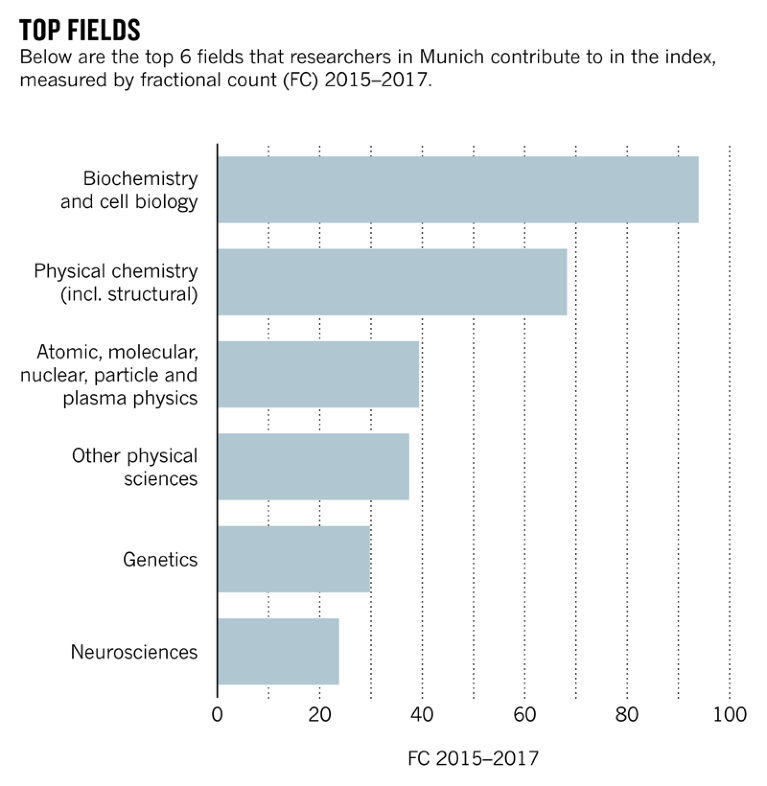

Centuries-old competition between esteemed universities for the best ideas and talent has driven continually rising standards in Munich, while their close links have fuelled a collaborative culture. Bavaria’s capital, Munich is the second leading science city in Germany after Berlin, when measured on its contribution to the authorship of articles in the 82 high-quality research journals in the Nature Index, a metric known as fractional count (FC). It places sixth in Europe, behind bigger metropolises, Paris and London.

Part of Nature Index 2018 Science Cities

Strong institutional networks are a core strength of Munich, says Gerhard Müller, a structural mechanics engineer, and a vice president at Technical University of Munich (TUM). But this tight-knit community has recently been rocked by a series of scandals that could herald major institutional change in the long term.

With 17 higher-education institutes, Munich is second only to Berlin as the largest university centre in Germany. Standing out among them are two public universities, Ludwig Maximilians University (LMU), with an FC in 2017 of 179.41, and TUM, with an FC of 128.79.

Founded in 1472, LMU supports more than 6,000 researchers covering the breadth of social and natural sciences. TUM, its counterpart in size, was established several centuries later in 1868 and specifically focusses on the natural, life and applied sciences.

Healthy rivalry

Georg Kääb, managing director of the Bavarian biotech cluster, BioM, a consortium for the biotechnology sector in the region, says Munich maintains its standing because of the constant competition for the best ideas and talent between the two universities.

Their rivalry plays out in the annual Leibniz prizes, Germany’s premier research awards bestowed by the German Research Foundation (DFG). In 2016, computer scientist Daniel Cremers from TUM received the award for advances in computer vision and reconstruction of three-dimensional objects from 2D images. A year later, biologist Karl-Peter Hopfner from LMU won the prize for his work on DNA repair and decoding the mechanism of a DNA damage sensor. And in 2018, Veit Hornung, an immunologist at the same university, was recognized for his work on clarifying how cells detect and combat viruses.

Source: Nature Index

LMU and TUM were two of only three universities to be awarded additional grants in the first round of the German Universities Excellence Initiative, launched in 2006. The initiative is an effort by the German government to strengthen research universities and create internationally competitive centres. Over the past decade, LMU and TUM have received €21 million (US$24.4 million) annually through the programme. Sigmund Stintzing, a physicist and vice president at LMU, says the success of the excellence initiative has strengthened the university’s commitment to the natural sciences, with plans to build a new campus that will feature a nanotechnology institute, scheduled to open in 2019.

Research circuit

The universities ensure a constant supply of well-trained students for the community of research institutes in the city — an important resource for principal investigators, says biophysicist, Petra Schwille.

Schwille is director for cellular and molecular biophysics at the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry in Martinsried, a suburb of Munich. She is part of a team of astronomers, biologists, chemists and geoscientists from five research centres in Munich, including TUM and LMU, testing theories on the emergence of life on Earth. The group is funded by an initial four-year grant from the DFG through its €164 million Collaborative Research Centres programme to pursue long-term and innovative projects.

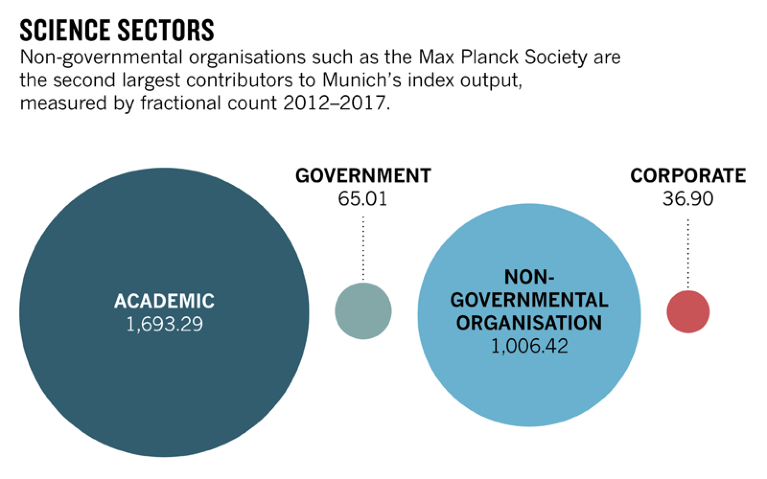

Source: Nature Index

Schwille’s institute is one of 11 located in the larger metropolitan area of Munich, which are part of the prestigious basic science organisation Max Planck Society, headquartered in the city. Also based in Munich is the Fraunhofer Society. With 72 research institutes across Germany and 25,000 employees, Fraunhofer is the largest applied science organisation in Europe.

The German Research Center for Environmental Health, and the German Aerospace Center are also in Munich. Both are part of the Helmholtz Association, yet another national research network, which specializes in infrastructure-intensive projects such as aeronautics and oceanography, and boasts almost 40,000 employees.

All welcome

Munich is the third-most-populous city in Germany, after Berlin and Hamburg. But its national research prominence is partly due to wealth rather than size. The southern state of Bavaria has the highest GDP per capita of the 13 area-states. As such, Bavaria can afford to grant its universities a budget of €7 billion a year, more than twice the amount provided by the capital, Berlin.

Schwille also appreciates the general quality of life in the city. “The nature around Munich is fantastic and the city culture very inspiring,” she says. Munich regularly ranks among the top ten cities in the world for quality of life. In the Mercer Quality of Living Survey 2018, for example, it holds third place.

Source: Nature Index/Dimensions from Digital Science

The city also welcomes diversity, which gives it an edge over emerging science states. Eastern German cities, Dresden and Leipzig, for example, have recently founded the Max Planck institutes of molecular cell biology and genetics, and evolutionary anthropology. But the rise of the populist right in the east has made it more difficult for them to attract foreign students and researchers. “Compared to Dresden, Munich is definitely a much nicer and safer place for people who do not look and speak German,” says Schwille. More than 15,000 foreign students are based in Munich, with some 20% of PhDs at TUM awarded to international students.

On the downside, the city is growing rapidly, and with it comes traffic and higher costs of living. Rent is especially a problem, being roughly 50% higher than in Berlin and twice as high as in Dresden.

Trialling times

A number of high-profile research institutions in Germany have recently been shaken by scandals, including in Munich. Allegations of bullying against a director of the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics in Garching, a town on the northern edge of Munich, surfaced this year. And in 2017, the Max Planck Institute for Psychiatry in Munich faced charges of financial fraud, plagiarism, and bullying. It is unclear whether the cases will affect Munich’s good science name.

Fabian Schmidt, a cosmologist at the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics, says that he was concerned that the allegations would taint the institute’s reputation, but it is too early to determine their impact on doctoral student recruitment.

In response to the revelations, Max Planck Society commissioned an anonymous employee survey, and has hired a law firm to which scientists can anonymously bring allegations, which the firm will investigate independently.

The institute has also released a new code of conduct for professional interactions, which is a step in the right direction, says Schmidt. He acknowledges, though, that while it applies to all personnel, including directors, it is potentially not an adequate mechanism for enforcement in the event that another director is suspected of abusive conduct.

Source: Nature Index

Many scientists point to the entrenched hierarchical structures in Germany’s research institution as the underlying issue. The dependency between the majority of scientists with fixed-term contracts and the few permanent professorships is an ideal breeding ground for abuse, says Jule Specht, a psychologist at Humboldt University of Berlin, who has been campaigning for department structures that give scientists more independence. Professorships in Germany are typically the only long-term positions available in academia but they are relatively scarce. “The unattractive hierarchical structure makes Germany lose young scientists,” she adds.

Counting capital costs

Counting capital costs

The cape of change

The cape of change

A venture under pressure

A venture under pressure

City links

City links

Discovery central

Discovery central

Peripheral forces

Peripheral forces

Standing firm

Standing firm