-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Adrian Florea, De Facto States: Survival and Disappearance (1945–2011), International Studies Quarterly, Volume 61, Issue 2, June 2017, Pages 337–351, https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqw049

Close - Share Icon Share

De facto states—polities, such as Abkhazia (Georgia) or the Donetsk People’s Republic (Ukraine), that appropriate many trappings of statehood without securing the status of full states—have been a constant presence in the postwar international order. Some de facto states, such as Northern Cyprus, survive for a long period of time. Others, including Tamil Eelam in Sri Lanka, are forcefully reintegrated into their parent states. Still others, such as Aceh in Indonesia, disappear as a result of peacemaking. A few, such as Eritrea, successfully transition to full statehood. What explains these very different outcomes? I argue that four factors account for much of this variation: the extent of military assistance that separatists receive from outside actors, the governance activities conducted by separatist insurgents, the fragmentation of the rebel movement, and the influence of government veto players. My analysis relies on an original dataset that includes all breakaway enclaves from 1945 to 2011. The findings enhance our understanding of separatist institutional outcomes, rebel governance, and the conditions that sustain nonstate territorial actors.

From Somaliland in the Horn of Africa to, more recently, the Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics in Eastern Ukraine, de facto states function as alternative structures of authority in a post-1945 international order dominated by recognized nation-states. De facto states are separatist polities that rule autonomously over portions of territory, establish governance structures, but lack international legitimacy. De facto states bestride the realm between rebellion and statecraft; they raise important questions about the conditions under which state and nonstate actors share authority in the contemporary system. These entities attempt to exercise a legitimate—although not legal—monopoly on violence, acquire concrete attributes of statehood, and institutionalize alternate socio-political orders. Dismissed by some as fleeting buffer enclaves and heralded by others as viable alternatives to nation-states, de facto states exercise practical sovereignty over swaths of seemingly anarchic spaces. Their existence highlights the need to depart from static conceptions of authority and look at the full range of actors that appropriate sovereign functions (Ahram and King 2011; Bartleson 2001; Clunan and Trinkunas 2010; Florea 2014).

Despite their resilience alongside recognized countries, de facto states receive comparatively less attention. We know a lot about when states are born or die (Coggins 2014; Fazal 2007; Hale 2008; Roeder 2007; Spruyt 1994; Tilly 1990; Wimmer 2013), but our understanding of the conditions under which de facto states survive or perish remains partial. The current international order places a great deal of importance on recognition as a condition for sovereign statehood. This makes the persistence of de facto states puzzling. Also surprising is the fluidity in their lifespan. Some, like Western Sahara, have adapted quite well to inauspicious systemic conditions and have survived for a long period of time. Others, like Biafra, Nigeria (1967–1970), failed to “fit in” and disappeared (Caspersen 2012; Pegg 1998). It is the variation in de facto state trajectories that lies at the core of this study. Specifically, I ask two questions. First, why do some de facto states disappear while others survive? And, second, what explains the fate of those that do disappear? Why do some end up being forcefully or peacefully reintegrated into their parent states while others make the transition to full statehood?1

My explanation for the variability in de facto state outcomes focuses on the commitment problems engendered by four factors: the extent of military support that separatists receive from outside patrons; the degree of state building in the breakaway region (the extent of governance activities conducted by rebels);2 the level of fragmentation within the separatist insurgency; and the influence of government veto players. Each of these factors shapes the power configuration between the parent state and the separatists as well as the power balance among actors within the parent state and the separatist insurgency, and, in so doing, creates commitment issues that push a de facto state toward a particular trajectory.

Using an original dataset with all de facto states from 1945 to 2011, I find that these territorial nonstate actors are less likely to be peacefully reintegrated into their parent states when they receive substantial military assistance from foreign sponsors, when they are fragmented, and when they engage in extensive state building (governance) activities. Perhaps counterintuitively, the results also show that a negotiated reintegration of separatist enclaves is more likely when the parent state government has multiple veto players. Moreover, de facto states that are internally fractured and build solid statelike structures find themselves better positioned to make the transition to statehood. At the same time, statehood emerges as a less likely outcome when separatists receive considerable external military support and when the parent state is internally divided.

The article proceeds as follows. The first section offers an operational definition of the de facto state which situates it among the larger population of nonstate actors that operate violence monopolies. The second section develops a credible commitment explanation for de facto states’ resilience which yields several hypotheses about the conditions which precipitate or inhibit de facto states’ disappearance. The third section tests these hypotheses empirically and addresses the main implications of the findings. Finally, the fourth section proposes an important direction for future research.

De Facto States as Nonstate Actors

De facto states are separatist polities that exercise a monopoly over the use of violence in a given area but lack international legal sovereignty. Yet, various types of insurgent actors—for example, militias, terrorists, or warlords—institutionalize monopolies of force. To understand what de facto states are, and are not, we need to locate them among the population of rebel organizations that hold monopolies on violence. Thus, I define de facto states as polities that: (1) belong to (or are administered by) a recognized country, but are not colonial possessions; (2) seek some degree of separation from that country, and have either declared independence or demonstrated aspirations for independence—for example through a referendum or a sovereignty declaration;3 (3) exert military control over a territory, or portions of territory, inhabited by a permanent population; (4) are not condoned by the governments that hold juridical sovereignty over their territory; (5) perform at least basic governance functions, such as provision of social and political order; (6) lack international legal sovereignty;4 and (7) exist for at least 24 months.

The operational indicators yield a population of 34 de facto states (Table 1), and distinguish these enclaves from territories controlled by other types of rebel actors. De facto states are different from warlord areas (for example spaces ruled by the Lord’s Resistance Army in Uganda), where the goal of the insurgency is not self-determination and where there is little governance beyond the production of violence. De facto state rebels resemble the Olson's (1993) “stationary bandits” who control and govern territory rather than the “roving bandits” who roam and pillage. Also, de facto states differ from territories governed by rebels who aim to overthrow the government, like UNITA-controlled areas in Angola (1975–2002). While these organizations may share with de facto states some characteristics, like territorial control and governance, the goal of the insurgency is regime change rather than self-determination. Finally, de facto states are separate from areas ruled by pro-state paramilitary groups, such as government-sponsored anti-FARC militias in Colombia.

Population of de facto states (1945–2011)

| De facto state . | Parent state . | Emergence . | Disappearance . | Type of disappearance . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Katanga | Congo (DRC) | 1960 | 1963 | forceful reintegration |

| Biafra | Nigeria | 1967 | 1970 | forceful reintegration |

| Krajina | Croatia | 1991 | 1995 | forceful reintegration |

| Chechnya | Russia | 1991 | 1999 | forceful reintegration |

| Anjouan | Comoros | 1997 | 2008 | forceful reintegration |

| Tamil Eelam | Sri Lanka | 1984 | 2009 | forceful reintegration |

| Rwenzururu Kingdom | Uganda | 1963 | 1982 | peaceful reintegration |

| Găgăuzia | Moldova | 1991 | 1995 | peaceful reintegration |

| Bougainville | Papua New Guinea | 1975 | 1997 | peaceful reintegration |

| Eastern Slavonia | Croatia | 1995 | 1998 | peaceful reintegration |

| Ajaria | Georgia | 1991 | 2004 | peaceful reintegration |

| Aceh | Indonesia | 2001 | 2005 | peaceful reintegration |

| Karen State | Burma | 1949 | — | alive |

| Kachin State | Burma | 1961 | — | alive |

| Taiwan | China | 1971 | — | alive |

| Mindanao | Philippines | 1973 | — | alive |

| TRNCa | Cyprus | 1974 | — | alive |

| Western Sahara | Moroccob | 1974 | — | alive |

| Cabinda | Angola | 1975 | — | alive |

| Casamance | Senegal | 1982 | — | alive |

| Abkhazia | Georgia | 1991 | — | alive |

| Kurdistan | Iraq | 1991 | — | alive |

| Nagorno-Karabakh | Azerbaijan | 1991 | — | alive |

| Puntland | Somalia | 1991 | — | alive |

| Somaliland | Somalia | 1991 | — | alive |

| South Ossetia | Georgia | 1991 | — | alive |

| Transnistria | Moldova | 1991 | — | alive |

| Republika Srpska | Bosnia-Herzegovina | 1992 | — | alive |

| Palestine | Israelc | 1995 | — | alive |

| Gaza | Palestined | 2007 | — | alive |

| Eritrea | Ethiopia | 1964 | 1993 | statehood |

| East Timor | Indonesia | 1975 | 2002 | statehood |

| Kosovoe | Serbia | 1998 | 2008 | statehood |

| South Sudan | Sudan | 1956 | 2011 | statehood |

| De facto state . | Parent state . | Emergence . | Disappearance . | Type of disappearance . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Katanga | Congo (DRC) | 1960 | 1963 | forceful reintegration |

| Biafra | Nigeria | 1967 | 1970 | forceful reintegration |

| Krajina | Croatia | 1991 | 1995 | forceful reintegration |

| Chechnya | Russia | 1991 | 1999 | forceful reintegration |

| Anjouan | Comoros | 1997 | 2008 | forceful reintegration |

| Tamil Eelam | Sri Lanka | 1984 | 2009 | forceful reintegration |

| Rwenzururu Kingdom | Uganda | 1963 | 1982 | peaceful reintegration |

| Găgăuzia | Moldova | 1991 | 1995 | peaceful reintegration |

| Bougainville | Papua New Guinea | 1975 | 1997 | peaceful reintegration |

| Eastern Slavonia | Croatia | 1995 | 1998 | peaceful reintegration |

| Ajaria | Georgia | 1991 | 2004 | peaceful reintegration |

| Aceh | Indonesia | 2001 | 2005 | peaceful reintegration |

| Karen State | Burma | 1949 | — | alive |

| Kachin State | Burma | 1961 | — | alive |

| Taiwan | China | 1971 | — | alive |

| Mindanao | Philippines | 1973 | — | alive |

| TRNCa | Cyprus | 1974 | — | alive |

| Western Sahara | Moroccob | 1974 | — | alive |

| Cabinda | Angola | 1975 | — | alive |

| Casamance | Senegal | 1982 | — | alive |

| Abkhazia | Georgia | 1991 | — | alive |

| Kurdistan | Iraq | 1991 | — | alive |

| Nagorno-Karabakh | Azerbaijan | 1991 | — | alive |

| Puntland | Somalia | 1991 | — | alive |

| Somaliland | Somalia | 1991 | — | alive |

| South Ossetia | Georgia | 1991 | — | alive |

| Transnistria | Moldova | 1991 | — | alive |

| Republika Srpska | Bosnia-Herzegovina | 1992 | — | alive |

| Palestine | Israelc | 1995 | — | alive |

| Gaza | Palestined | 2007 | — | alive |

| Eritrea | Ethiopia | 1964 | 1993 | statehood |

| East Timor | Indonesia | 1975 | 2002 | statehood |

| Kosovoe | Serbia | 1998 | 2008 | statehood |

| South Sudan | Sudan | 1956 | 2011 | statehood |

Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus

Administered by Morocco

Under Israeli occupation

Under Hamas control

Not a UN member.

Population of de facto states (1945–2011)

| De facto state . | Parent state . | Emergence . | Disappearance . | Type of disappearance . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Katanga | Congo (DRC) | 1960 | 1963 | forceful reintegration |

| Biafra | Nigeria | 1967 | 1970 | forceful reintegration |

| Krajina | Croatia | 1991 | 1995 | forceful reintegration |

| Chechnya | Russia | 1991 | 1999 | forceful reintegration |

| Anjouan | Comoros | 1997 | 2008 | forceful reintegration |

| Tamil Eelam | Sri Lanka | 1984 | 2009 | forceful reintegration |

| Rwenzururu Kingdom | Uganda | 1963 | 1982 | peaceful reintegration |

| Găgăuzia | Moldova | 1991 | 1995 | peaceful reintegration |

| Bougainville | Papua New Guinea | 1975 | 1997 | peaceful reintegration |

| Eastern Slavonia | Croatia | 1995 | 1998 | peaceful reintegration |

| Ajaria | Georgia | 1991 | 2004 | peaceful reintegration |

| Aceh | Indonesia | 2001 | 2005 | peaceful reintegration |

| Karen State | Burma | 1949 | — | alive |

| Kachin State | Burma | 1961 | — | alive |

| Taiwan | China | 1971 | — | alive |

| Mindanao | Philippines | 1973 | — | alive |

| TRNCa | Cyprus | 1974 | — | alive |

| Western Sahara | Moroccob | 1974 | — | alive |

| Cabinda | Angola | 1975 | — | alive |

| Casamance | Senegal | 1982 | — | alive |

| Abkhazia | Georgia | 1991 | — | alive |

| Kurdistan | Iraq | 1991 | — | alive |

| Nagorno-Karabakh | Azerbaijan | 1991 | — | alive |

| Puntland | Somalia | 1991 | — | alive |

| Somaliland | Somalia | 1991 | — | alive |

| South Ossetia | Georgia | 1991 | — | alive |

| Transnistria | Moldova | 1991 | — | alive |

| Republika Srpska | Bosnia-Herzegovina | 1992 | — | alive |

| Palestine | Israelc | 1995 | — | alive |

| Gaza | Palestined | 2007 | — | alive |

| Eritrea | Ethiopia | 1964 | 1993 | statehood |

| East Timor | Indonesia | 1975 | 2002 | statehood |

| Kosovoe | Serbia | 1998 | 2008 | statehood |

| South Sudan | Sudan | 1956 | 2011 | statehood |

| De facto state . | Parent state . | Emergence . | Disappearance . | Type of disappearance . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Katanga | Congo (DRC) | 1960 | 1963 | forceful reintegration |

| Biafra | Nigeria | 1967 | 1970 | forceful reintegration |

| Krajina | Croatia | 1991 | 1995 | forceful reintegration |

| Chechnya | Russia | 1991 | 1999 | forceful reintegration |

| Anjouan | Comoros | 1997 | 2008 | forceful reintegration |

| Tamil Eelam | Sri Lanka | 1984 | 2009 | forceful reintegration |

| Rwenzururu Kingdom | Uganda | 1963 | 1982 | peaceful reintegration |

| Găgăuzia | Moldova | 1991 | 1995 | peaceful reintegration |

| Bougainville | Papua New Guinea | 1975 | 1997 | peaceful reintegration |

| Eastern Slavonia | Croatia | 1995 | 1998 | peaceful reintegration |

| Ajaria | Georgia | 1991 | 2004 | peaceful reintegration |

| Aceh | Indonesia | 2001 | 2005 | peaceful reintegration |

| Karen State | Burma | 1949 | — | alive |

| Kachin State | Burma | 1961 | — | alive |

| Taiwan | China | 1971 | — | alive |

| Mindanao | Philippines | 1973 | — | alive |

| TRNCa | Cyprus | 1974 | — | alive |

| Western Sahara | Moroccob | 1974 | — | alive |

| Cabinda | Angola | 1975 | — | alive |

| Casamance | Senegal | 1982 | — | alive |

| Abkhazia | Georgia | 1991 | — | alive |

| Kurdistan | Iraq | 1991 | — | alive |

| Nagorno-Karabakh | Azerbaijan | 1991 | — | alive |

| Puntland | Somalia | 1991 | — | alive |

| Somaliland | Somalia | 1991 | — | alive |

| South Ossetia | Georgia | 1991 | — | alive |

| Transnistria | Moldova | 1991 | — | alive |

| Republika Srpska | Bosnia-Herzegovina | 1992 | — | alive |

| Palestine | Israelc | 1995 | — | alive |

| Gaza | Palestined | 2007 | — | alive |

| Eritrea | Ethiopia | 1964 | 1993 | statehood |

| East Timor | Indonesia | 1975 | 2002 | statehood |

| Kosovoe | Serbia | 1998 | 2008 | statehood |

| South Sudan | Sudan | 1956 | 2011 | statehood |

Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus

Administered by Morocco

Under Israeli occupation

Under Hamas control

Not a UN member.

De facto states warrant investigation for multiple reasons. For one, they illuminate the diversity of units populating the international system. De facto states are polities that have adapted well to a world of recognized countries while staying outside their grasp. They vividly illustrate the need to regard political order in ways other than sovereign statehood (Acharya 2014; Lemke 2006; Paul 1999; Sharman 2013; Staniland 2012; Vinci 2008). Sovereignty is divisible both as a matter of principle and as a matter of experience, and is shared by state and nonstate actors alike (Krasner 1999). By recognizing no higher authority and creating spaces of self-rule, de facto states project an image of sovereignty as a malleable and variable concept (Florea 2012). As alternate structures of political organization, these entities fulfill roles often considered the exclusive preserve of states; they emerge as contenders for authority in an era of contested sovereignty. Their resilience alongside state units in the post-1945 environment indicates an inherent distribution of practical authority between state and nonstate actors.5

Relatedly, de facto states help us better understand the provision of governance in areas beyond state control. These polities institutionalize alternative modes of governance and, in some cases (such as Somaliland), prove more effective at developing administrative structures than does the nominal territorial sovereign. De facto separation marks a disjuncture between the locus of (international legal) authority and the locus of governance. In most of these statelets, separatists completely dislodge the sovereign power and assume the burdens of government: they set up separate institutions, maintain order, levy taxes, and administer justice.

De facto states also capture the dynamic character of separatism. Recent scholarship reveals that de facto separation does not amount to successful secession, but constitutes a “near miss” (Laitin 2007, 17). This observation underlies a tension in current works: though historical evidence suggests that separatism is a matter of degree, we typically analyze this phenomenon in binary terms—separation either succeeds or fails (Saideman 2001; Sambanis 2004; Tir 2005; Toft 2010; Walter 2009). Separatism includes demands for the creation of separate states as well as for broad measures of autonomy or quasi-independence (Horowitz 2000, 231). This perspective conveys a dynamic process of bargaining that can yield various institutional forms of separation that are more or less stable.6 Yet, most of the literature remains focused on a dichotomous outcome: unsuccessful or successful separation. Conventional explanations for why some separatist struggles succeed while others fail focus on the characteristics of the actors involved in the dispute (separatist organization, ethnic group, government), the environment in which these actors interact, the violent or nonviolent tactics employed to pursue their objectives, or outside intervention (Sorens 2012; Regan 2000; Toft 2003; Walter 2002). Degrees of separation rarely enter the analysis. With some exceptions (Chapman and Roeder 2007; Roeder 2007; Seymour 2008), separatism is black-boxed: current works leave unmeasured and theoretically unexplored much of the variation in institutional outcomes that lie between unsuccessful and successful separation.

This article attempts to bridge this gap by investigating the conditions that make a particular type of separatist outcome, de facto separation, more or less durable. Specifically, it seeks to explain why some de facto states survive while others disappear. Drawing inspiration from the larger literature on civil war and separatism, and the specialized works on de facto states, I offer below a credible commitment account for de facto state trajectories. The central contention is that the power distribution between and within the government and the separatist insurgency produces different kinds of commitment problems that translate into different types of outcomes for these enclaves. The next section develops this argument.

Credible Commitment and De Facto State Outcomes

I begin with the premise that credible commitment functions as the key mechanism that shapes bargaining between separatists and governments and, therefore, causes much of the variation in de facto state outcomes (forceful reintegration, peaceful reintegration, transition to statehood). Bargaining breakdown in conflicts over de facto states is less likely to be triggered by other rationalist drivers of war—informational asymmetry (uncertainty about capabilities and resolve) or issue indivisibility (Fearon 1995). Ample case study evidence indicates that de facto states operate in information-rich environments (Caspersen 2012; Caspersen and Stansfield 2010; Lynch 2004; Pegg 1998). Prior episodes of conflict or contention, geographical contiguity, frequent interactions at the de facto border, and mutual monitoring reduce the uncertainty that actors have about their capabilities and resolve.7 Similarly, issue indivisibility is unlikely to emerge as the main obstacle to successful bargaining between the separatists and the parent state. This is because, compared to disputes over government, disputes over territory are more amenable to resolution since there exists, in principle, a division of the territory that both parties would be content with (Walter 2002, 2009). Viewed through this lens, indivisibility is not an inherent property of the disputed territory but a by-product of bargaining failure (Goddard 2009). Hence, credible commitment mechanisms are likely to play a key role in complicating bargaining between separatists and governments.

Commitment problems emerge in most warring group interactions (Christia 2012; Cunningham 2014; Pearlman 2011). Antagonists often prove unable to commit themselves to abide by an agreement. They also face incentives to renege on agreements. Recent works overwhelmingly focus on commitment problems as barriers preventing rebels from entering into or reneging on an agreement with the government. This line of inquiry holds that the proliferation of civil war participants expands the range of preferable agreements and reduces actors’ willingness, or ability, to abide by a deal (Bakke, Cunningham, and Seymour 2012; Cunningham 2011). By disaggregating the number of conflict parties, this approach marks a welcome departure from the unitary actor assumption that undergirds commitment-centered explanations of warfare. It provides a more realistic view of the conditions that lead to bargaining collapse in internal conflicts. Nonetheless, key challenges remain: “not to identify commitment problems per se, but rather to identify mechanisms that provide important insights into the forces underlying…persistent inefficient behavior” (Powell 2012, 46). Without attention to its origin, a commitment problem becomes nothing but a “catch-all label” that doesn’t tell us much about why some conflicts last more than others unless we examine the relationship among different kinds of commitment problems and the outcomes they generate (Powell 2012, 51).

In conflicts over de facto states, the preference structure for the government and the rebels tends to shift in relation to the dyadic power distribution and internal struggles. The relative power distribution operates at interrelated levels—the dyadic/interaction level and the actor level (government, de facto state)—to produce different kinds of commitment problems with varying implications for outcomes. Stated otherwise, the power distribution between the government and the insurgency (a structural bargaining condition) as well as the power struggles within each of them (a structural organizational condition) alter the strategic environment in unique ways to generate various commitment problems and produce divergent trajectories for de facto states. The relative capability between the separatists and the parent state as well as these actors’ internal struggles are really doing the work behind de facto state survival or disappearance by shaping incentives to commit to a deal or continue fighting. The ultimate fate of a separatist statelike entity revolves around dynamics of two-level power “games” (Putnam 1988)—power “games” at the dyadic/interaction level and power “games” at the actor (government, separatist) level—which affect actors’ willingness or ability to commit to an agreement.

Power Distribution and Commitment Problems at the Dyadic Level

Anticipated shifts in the power distribution function as major obstacles to credible commitment across all types of conflict. Expectations about adverse changes in the relative power balance reduce actors’ desirability of striking a deal or committing to an agreement that has already been reached. Applied to de facto states, this logic suggests that a settlement that is preferable in the present cannot be sustained for the long term because changes in the power distribution between the separatists and the government alter the appeal of a deal. Shifts in the power balance reverberate throughout the strategic environment in which the de facto state and the government operate, impinge on actors’ discount rate (the rate at which they discount future benefits), and raise barriers to successful bargaining. With a relative power balance in flux, neither side has the incentive or the ability to commit to a settlement.

I make two assumptions about the power distribution between the de facto state and the government. First, I assume that this power distribution varies, depending on actors’ military resources and mobilizational effectiveness. Second, I assume that commitment problems become more acute when the power distribution is altered by the capabilities of the de facto state rather than by those of the parent state. Thus, even with a change in the power distribution in government’s favor (through external assistance, for instance), it will retain a preference for peaceful resolution. After all, warfare is costly and comes with a baggage of uncertainty about the evolution of hostilities and the contours of the post-conflict environment.8 The larger literature on the politics of self-determination and the more specialized works on de facto states suggest that, in an attempt to maintain military parity with the government, separatists engage in both external and internal balancing behavior. The former strategy involves attracting external military support while the latter centers around state building activities that allow separatists to acquire domestic legitimacy and maintain mobilization against the government. The next section explores the processes through which these two factors might alter the dyadic power distribution, exacerbate commitment problems, and propel a de facto state toward a particular path.

External Military Support

As actors interested in their survival, de facto states have a fundamental need to mobilize resources. De facto states’ survival hinges on their capacity to balance militarily against the parent state. Functionally, they are undifferentiated from sovereign countries in that the survival imperative compels them to balance both externally and internally. Securing military support from an external patron is a common form of external balancing that allows separatists to maintain mobilization. Military support can come in various forms: arms, communication technologies, and hardware; personnel; training for rebel troops; provision of safe havens (Carter 2012; Salehyan, Gleditsch, and Cunningham 2011).

For the de facto state, military assistance galvanizes hopes of sustained self-rule. For the parent state, outside support for the insurgency alters its incentives to resolve the dispute peacefully. To forestall adverse shifts in the power distribution triggered by external assistance for the rebellion, the government might contemplate military action. At the same time, military aid from sponsors injects vital lifeblood into the arteries of a de facto state by providing rebels with the resources needed to prevent forceful reintegration. Outside support enables de facto state leaders to resist attempts at forceful reintegration, and amplifies commitment problems because, in the presence of military assistance, rebels will likely radicalize their demands (Jenne 2007). When negotiating with the parent state, separatists may promise “not to seek independence if greater territorial autonomy is granted, but may have difficulty convincing the government that they will not escalate their demands” if they benefit from external sponsorship (Walter 2009, 37). De facto state leaders are less likely to accept an autonomy deal when they are confident of resources that will allow them to maintain military parity with the government. Essentially, with extensive external sponsorship, rebels have few incentives to credibly commit to a settlement that gives them anything less than the status quo.

Some argue that we should observe less support for separatists because separatism threatens established boundaries and, hence, the stability of the international system (Saideman 2002, 28). However, many de facto states receive substantial assistance, which indicates that third parties are more concerned with immediate geopolitical goals than with larger systemic considerations. In many situations, such as Russia’s support for Abkhazia, South Ossetia, and Transnistria (Blakkisrud and Kolstø 2011; Caspersen 2012; King 2001; Kolstø 2006; Lynch 2004; Pegg 1998), powerful sponsors throw their weight behind a de facto state ostensibly to protect ethnic kin but in reality to pursue larger geostrategic objectives such as destabilizing host regimes (Jenne 2007, 126). Sponsorship lowers the probability that the de facto state will be forcefully reintegrated into the parent state, and hinders the prospects for a settlement. With a strong supporter in their backyard, separatists will gain confidence at the negotiating table, and will likely escalate their demands rather than acquiesce to autonomy offers made by the government.

While sponsorship enables de facto states to survive for longer periods of time, it can also undermine separatists’ independence aspirations. With external patronage for the rebellion, the parent state will be less inclined to commit to a final agreement through which it recognizes the de facto state’s independence. In a scenario of external military assistance for the separatists, the government will likely oppose any agreement that grants independence to the breakaway enclave. Additionally, other countries might be reluctant to recognize the independence of these entities since they will perceive them as mere “puppets” of regional or global powers (Salehyan, Gleditsch, and Cunningham 2011, 717). For instance, in their quest for independence, Abkhaz separatists have unsuccessfully tried to dissociate themselves from Moscow’s patronage by projecting the image of a legitimate right for statehood based on prior separate existence (Bakke etal. 2014). Although Abkhaz politics often unfolds contrary to Russia’s preferences (Kremlin-backed presidential candidates have twice been defeated at the polls in 2004 and 2011), the close military and economic cooperation between Moscow and Abkhazia casts an aura of patron–client dependence that delegitimizes the Abkhaz independence struggle in the eyes of the international community. Therefore, these rationales suggest that:

H1:The greater the extent of external military support for the separatists, the lower the likelihood of de facto state reintegration (peaceful or forceful) or transition to statehood.

State Building

De facto state leaders face a paradox: reliance on external patrons strengthens them militarily, but also makes them vulnerable. For various reasons, sponsors may be unwilling or unable to bolster a de facto state. Fluctuations in external military support can jeopardize a de facto state’s survival prospects. For instance, separatists in Krajina, a Serb enclave of Croatia that declared independence in 1991, could not consistently rely on Serbia’s military support because Belgrade pursued its own interests and was more interested in controlling the decision-making process in the province than ensuring its survival. Serbian patronage was more of a curse than a blessing because it was intermittent and encouraged splintering within the rebel movement. By supplying rival factions with both coercive and economic resources, Belgrade actually contributed to the demise of the de facto state since divisions among separatists stymied their efforts to coordinate military activities against the government (Caspersen 2012, 104). Unsurprisingly, in 1995 Krajina was forcefully reintegrated into the parent state.

The Krajina example conveys a straightforward message: external patronage can be a two-way street. It may enhance a de facto state’s survival prospects, but it may also limit its room for maneuver. Strategic interests fluctuate—international, regional, or domestic considerations frequently lead patron states to rethink their priorities and recalibrate their policies toward friends and foes alike. The unpredictability of external assistance coupled with concerns for loss of autonomy and legitimacy make rebels aware that they also need a domestic resource base, one generated through state building (governance) activities. The imperative of balancing against the government forces de facto states to centralize power, expand the institutional apparatus, and extract resources. The threat of war with the parent state pushes rebels to create an alternative order with state making consequences. Beneath the apparent chaos of de facto separation lies a reconfiguration of political order with processes functionally equivalent to state formation. State building can substantially affect de facto states’ viability. This form of internal balancing has important consequences: if it is large and sustained, it leaves behind solid institutional structures that create material bases for mobilization against the government. Many de facto states, such as Abkhazia or Transnistria, exhibit a sprawling bureaucracy akin to a sovereign country (Blakkisrud and Kolstø 2011): they have a separate government with functional ministries, separate health and education institutions and, in some cases, a separate central bank and local currency.

The establishment of a statelike architecture in rebel-held territory provides the actors with a mix of incentives. Governments may prefer a peaceful deal with the rebels, but cannot commit to it when the latter become “rulers of the domain” (Olson 1993). To forestall the institutionalization of separate rule on their territory, governments may contemplate violence as a mechanism for dispute resolution. However, rebel governance likely inhibits a de facto state’s forceful reintegration because it facilitates recruitment (the local population becomes invested in the alternative order) and resource mobilization (Arjona 2014). Rebel governance also decreases the prospects of peaceful reintegration. State building lowers the likelihood that de facto state leaders will accept an agreement that does not represent an improvement over the status quo. Decisions to develop a complex governance architecture signal resolve: by engaging in onerous state building projects, insurgent leaders communicate that nothing short of de facto separation would be acceptable in the long run. The opportunity costs of governance signal commitment to local rule, and affect the bargaining range such that separatists’ preference structure may exclude any deal that involves the enclave’s reintegration into the parent state. In Northern Cyprus, for instance, over the past four decades external support from Turkey coupled with a robust governance apparatus have made separatist leaders less willing to accept agreements that give them something less than what they already have (quasi-independence).

A high degree of state building could also increase the likelihood of transition to statehood. Governance consolidates the enclave’s separation, and sends a powerful signal that nothing short of independence would satisfy the rebels in the long run. The establishment of a separate statelike apparatus punctures any link that may remain between the parent state and the local population, and bolsters the enclave’s legitimacy for both domestic and international audiences. Separatist state builders claim that successful governance legitimizes their bid for independence and international recognition (Caspersen 2012). State building has historically been a key condition for admission into the club of internationally recognized states. In many cases of state emergence, polities claiming a right to statehood had to first demonstrate that they displayed statelike characteristics: control over territory, governance provision, and capacity to enter into relations with other units (Fabry 2010). In the contemporary environment where statehood is mutually constituted, earned sovereignty is no longer a sine qua non. A recent example is South Sudan, which in July 2011 entered the state system with inchoate governance structures. As exemplified by Kosovo’s case, however, earned sovereignty remains a valuable ticket of admission into the international arena. Kosovo’s independence was recognized by a plurality of UNSC-permanent members (the United States, France, Great Britain) only after meeting certain standards of good governance delineated by the international community.9 Hence, these arguments give rise to the second proposition:

H2:The greater the degree of state building in the de facto state, the lower the likelihood of reintegration (forceful or peaceful) and the higher the likelihood of transition to statehood.

Power Distribution and Commitment Problems at the Actor Level

Issues of commitment also arise with the variability in the power distribution at the actor level (the rebel movement and the government), and have ramifications for whether a de facto state survives or disappears. One the one hand, fragmentation among the separatists—an indicator of the relative power of various factions comprising the insurgency—can create insurmountable commitment hurdles. On the other hand, obstacles to successful bargaining can equally emanate from divisions within the parent state, more precisely from veto players—central government actors with potential for preventing change in policy. Below, I examine mechanisms through which rebel movement fragmentation and central government veto players shape the bargaining environment, and might catapult de facto states toward a certain trajectory.

Rebel Movement Fragmentation

Despite public claims of unity, many rebel movements include multiple factions with varying origins and agendas (Cunningham, Bakke, and Seymour 2012). As Pearlman and Cunningham (2012, 4) aptly note, “the norm in more recent civil wars is not coherent antagonists as much as shifting coalitions of groups with malleable allegiances and, at times, divergent interests.” Fragmentation among separatists complicates the bargaining environment and exacerbates commitment problems. With radical rebel factions intent on undermining autonomy negotiations, governments cannot commit to pursuing peaceful solutions. In fact, insurgent splintering provides parent states with incentives to destabilize the de facto state, playing one faction against the other. When the separatist enclaves suffer from internal schisms, they will be less successful in their attempt to balance against the government, and will be more vulnerable to forceful reintegration.10

Fragmentation is particularly pernicious in the context of autonomy negotiations between the separatists and the parent state because it expands actors’ preference dimension and, thus, shrinks the range of possible deals. Rebel factionalism creates a double-commitment problem, and makes peaceful reintegration elusive. On the government side, leaders might be reluctant to sign on to an agreement since, under conditions of acute splintering, rebels cannot commit to abide by it. On the rebel side, some factions might have rational incentives to continue their struggle rather than acquiesce to a deal with the parent state. In particular, those splinter groups with lower leverage over decision-making in the larger separatist movement worry that, if they partake into a deal with the government, the dominant faction cannot commit that it will not try to eliminate them in order to get a larger piece of the post-settlement “pie” (Christia 2012). Many de facto states display splintering dynamics wherein various armed factions crystallize around competing centers of authority.11 For example, in 1991 the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) split into two main factions, each claiming to be the “true” representative of the South Sudanese: a Dinka-dominated group led by John Garang (SPLA-Main/Torit) and a Nuer-dominated group (SPLA-United) led by Riek Machar and Lam Akol. Garang favored extensive autonomy for South Sudan (not least in deference to his Ethiopian patron who was engaged in a protracted struggle against Eritrean separatists) while SPLA-United openly sought an independent state. During the 1990s, SPLA’s efforts to reach a comprehensive autonomy deal with the government were hampered by splinter groups, such as SPLA-United, that were opposed to any deal involving reintegration into the parent state.

Fragmentation can also hamper de facto states’ independence aspirations. For example, a fragmented movement faces more difficulty than a cohesive one in its efforts to maintain full control over the territory and engage in effective governance activities. Both of these are often, but not always, key conditions for advancing a legitimate claim to statehood. In addition, rebel factions often gain more from the continuation of the struggle than from peace. In an independence scenario, the stronger organization in the rebel movement cannot guarantee that it will not turn on its weaker partners in order to capture complete control of the polity (Christia 2012, 21). Finally, other states, particularly those located in the proximity, may be reluctant to recognize a fragmented polity out of fear that factional infighting could morph into post-independence civil war with spillover potential, as is the case with South Sudan. Taken together, these rationales produce the third hypothesis:

H3:The greater the level of fragmentation in the de facto state, the higher the likelihood of forceful reintegration, and the lower the likelihood of peaceful reintegration or transition to statehood.

Government Veto Players

Parent state veto players—individual or collective actors that have institutional or extra-institutional means of preventing change (Tsebelis 2002)—can also block negotiated agreements. Any solution to conflicts involving de facto states inexorably involves redistribution of state power. Reintegration and transition to statehood have distributional implications for the relative power position of various groups within the parent state. Peaceful reintegration can upset the domestic balance of power since the cooptation of de facto state leaders within central or local government structures, which generally accompanies such agreements, might lead to a reshuffling of the ruling coalition. Faced with the prospect of a change in the ruling coalition, veto players have rational incentives to spoil agreements. The 2004 Annan Plan for Northern Cyprus provides a telling example of such a pattern: the plan failed mainly because it was rejected by Greek Cypriot leaders who were concerned about its distributional implications. The mechanism linking government veto players to commitment failures can operate irrespective of regime type. Democracies typically exhibit multiple veto players, such as legislators or regional administrators, who might dislike the distributional consequences implicit in a de facto state’s peaceful reintegration. Non-democratic regimes can also include a variety of veto players who might oppose a negotiated settlement that redistributes domestic power and influence.12

Paradoxical as it may seem at first sight, several actors within democratic or authoritarian parent states may have entrenched interests in preventing the disappearance of a de facto state: politicians may veto a negotiated solution for fear that it might alter the composition of the ruling coalition; the army’s modal reaction is to oppose self-determination demands;13 and those bureaucrats (tax officers, inspectors, border guards) who accrue substantial benefits from the lucrative trade in consumer goods, arms, narcotics, or even people across the often porous borders between the de facto state and the parent state will also be averse to any kind of change.14 With such an array of veto players with potential to block agreements, the government’s ability to enter negotiations and commit to a deal will be severely diminished. Therefore, the last expectation is:

H4:The higher the number of government veto players, the lower the likelihood of reintegration (forceful or peaceful), or transition to statehood.

Empirical Analysis

The hypotheses are tested with an original dataset of 34 de facto states in the post-WWII period (1945–2011).15 The unit of analysis is the de facto state-year, for a total of 780 observations. The dependent variable is de facto state duration—time in months from de facto state emergence until de facto state disappearance. De facto state emergence is observed in the month where a self-determination polity in an officially recognized country exhibits empirical sovereignty (military control over a territory), lacks universal recognition, is not condoned by the government, and engages in at least basic governance activities. If a de facto state was already in place before the declaration of independence of a newly formed parent state, then this date marks its emergence.16 The median survival time for de facto states is 345 months. The shortest-lived de facto state is Eastern Slavonia (Croatia), with a survival time of 25 months. The longest-lived de facto state is Karen State (Burma), with 756 months at the end of the observation period (December 2011).

Variables

The first hypothesis posited that outside military assistance exacerbates commitment problems and entrenches the continuation of the status quo. Sponsorship lowers the probability that a de facto state will be forcefully reintegrated into the parent state. External military support hinders the prospects for peaceful resolution by reducing separatists’ incentives to sign on to an agreement. An ideal measure for external Military Support would be an estimated dollar amount of military assistance a de facto state gets from other countries. The covert nature of military interactions between de facto states and external patrons limits the availability of such data. To circumvent this problem, I resort to a second-best measurement. Specifically, I construct a proxy that captures how much external military assistance a de facto state gets in any given year from state sponsors (Byman etal. 2001; Carter 2012). This variable is a score composed of five types of military external support, where each type of support receives equal weight: (1) weaponry and military hardware, (2) foreign military personnel, (3) foreign military advisors, (4) training for de facto state troops abroad, and (5) safe havens. The mean value for this covariate is 2.78, while the median value is 3. For example, Tamil Eelam registers a score of 4 for the period 1984–1988 when the LTTE received substantial support from India, and a score of 1 after 1988 when New Delhi withdrew its military assistance.17

The theory suggested that state building activities conducted by separatists can also affect a de facto state’s survival prospects in two ways. First, they provide the resources needed to mobilize against the government. Second, they confer a sense of legitimacy to the separatist movement. Both diminish separatists’ incentives to commit to an agreement that offers anything less than de facto separation. To gauge the effect of State Building on outcomes, I construct a variable that captures the number of statelike institutions that a de facto state exhibits in any given year. This variable captures the number of governance institutions that are present in each de facto state, and includes the following indicators: (1) an executive—coded as present if there is an executive authority that makes decisions in the de facto state, (2) a legislature and/or regional councils—coded as present if there is a legislative body in the de facto state capital and/or regional councils, (3) a court or semi-formalized legal system—coded as present if there is a formal or semi-formal juridical authority that adjudicates disputes between individuals or institutions in the de facto state, (4) a civilian tax system—coded as present if there are institutions for regularized extraction of taxes from the local population and/or from the diaspora, (5) an educational system—coded as present if the authorities in the de facto state establish a system of education that functions in parallel with or in lieu of the one provided by the government, (6) a welfare system—coded as present if the authorities in the de facto state establish a system of welfare (healthcare and/or pensions) that replaces or complements the one provided by the parent state, (7) institutions for foreign affairs—coded as present if the authorities in the de facto state conduct diplomacy by establishing missions abroad and engaging in contacts with IGOs and/or foreign governments, (8) a media or propaganda system—coded as present if the authorities in the de facto state establish media or propaganda outlets, (9) a police and/or gendarmerie system—coded as present if the authorities in the de facto state establish a system of domestic control (police and/or gendarmerie) that operates separately from the army, (10) a central banking system—coded as present if the authorities in the de facto state establish a central banking system that functions separately from the parent state’s banking network. The mean for this variable is 5.95, while the median is 6. For instance, Transnistria (Moldova) registers a value of 7 for its emergence year (1991) and a value of 10 for the period 1992–2011. Găgăuzia, a short-lived de facto state in the same country, registers a value of 2 on this variable for its entire survival period (1991–1995).

Another expectation held that the level of Fragmentation in the rebel movement can shape de facto state outcomes. Splintering can be perilous to a de facto state because military and political resources might be redirected toward internal power struggles rather than organized resistance against the government. Additionally, fragmentation erodes actors’ incentives or ability to commit to an agreement. To measure the level of fragmentation, I look at the number of factions that make demands on behalf of the de facto state (Bakke, Cunningham, and Seymour 2012; Cunningham, Bakke, and Seymour 2012). The higher the number of factions, the higher the level of fragmentation within the rebel movement. A faction is an organization that claims to represent the population of the de facto state and makes demands regarding the status of the enclave, such as reintegration into the parent state, limited autonomy, broad autonomy, no change in status, independence, (re)union with another state, or membership in a supra-national entity. A faction can be a political party, military organization, or civic group that operates within or outside the de facto state. The fragmentation variable ranges from 1 to 21, with a mean of 3.95 and a median of 3. Ajaria, Găgăuzia, and Rwenzururu Kingdom are the only de facto states with a single faction throughout their entire existence, while Palestine displays the largest number of factions—21 at the end of 2011.

One final theoretical expectation posited that central government Veto Players can block changes in the status quo. To assess the influence of veto players, I include a variable that measures the degree of veto opportunities in the parent state. I use Polity IV’s “executive constraints” variable as a proxy for the degree of veto opportunities. This indicator captures institutionalized constraints on the decision-making powers of the chief executives, whether individuals or collectivities. The advantage of this proxy is that it encompasses constraints on decision-making from both within and outside the government (constraints on decision-making can originate with legislatures, political parties, powerful advisers, private corporations, the army, or judicial bodies).18 The executive constraints variable is created on a 7-point scale, with 1 representing unlimited decision-making authority (no limitations on executive’s decisions) and 7 representing highly constrained decision-making authority (several veto players can block a decision). In the middle, a value of 3 represents slight to moderate limitation on decision-making authority, while a value of 5 represents substantial limitations on decision-making authority. The values 2, 4, and 6 are intermediate categories, bridging the gap between adjacent values. The mean value for this covariate is 4.03, while the median is 3.

In addition to the main predictors, I control for factors that can affect both the independent variables and the outcomes. One such factor is the de facto state’s Prior Status as an independent or autonomous territory. Although de facto states coalesce around concentrated minorities, their boundaries do not map neatly onto minority groups’ spatial distribution; instead, their frontiers tend to correspond to previous administrative units. For example, Somaliland’s borders roughly coincide with the eponymous British protectorate (1884–1960) and short-lived independent republic that on July 1, 1960, united with the former Italian Somaliland to form modern-day Somalia.19 When South Ossetia first declared independence from Georgia in May 1992, it claimed sovereignty over the territory of the former South Ossetian Autonomous Soviet Region (Oblast). Similarly, the Abkhaz de facto state formally encompasses the territory of the defunct Abkhaz Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic.

Prior status can emerge as a powerful determinant of separatist claims for at least two reasons. First, past institutional experience leaves behind institutional remnants, of formal or ideational fabric, that enable rebels to rally the local population around the separatist claim and mobilize resources. Prior existence as an independent/autonomous territory enhances the domestic legitimacy of the self-determination struggle, and lowers the cost of collective action. Institutional legacies not only reinforce ethnic identities and facilitate coordination, but also inculcate a territorial identity that is distinct from that of the core (Siroky and Cuffe 2015). Prior independence or autonomy gives de facto states ready-made institutions and networks of cooperation that increase separatists’ willingness, cohesion, and capacity to act against the government (Brancati 2006, 651; Lynch 2004, 24). Second, past institutions can serve as focal points or ready-made solutions for future cooperation between the rebels and the government. As the post-Soviet experience indicates, de facto states typically emerge out of lower-level jurisdictions, which may limit their capacity to organize a self-determination challenge. Roeder (2007, 10) holds that successful separations tend to be associated with higher-order jurisdictions, such as union republics, rather than with lower-level jurisdictions, like autonomous republics or autonomous regions. This logic suggests that institutional legacy may leave some de facto states structurally disadvantaged in their attempts to mobilize against the parent state. Operating with an impaired ability to mount a sustained resistance in an environment so averse to unilateral separations, de facto state leaders may use the territory’s institutional legacy as a building block for a future agreement with the government. A de facto state’s prior status can thus serve as a focal point for rebel–government cooperation because it minimizes uncertainty and costs for both sides. As Carter and Goemans (2011, 284) note, previous administrative boundaries coordinate actor expectations about bargaining outcomes. A legacy of autonomy, for instance, mitigates coordination problems related to the range of possible institutional configurations that can be produced by negotiations.

Relatedly, the historical legacy of a de facto state as a former Colony can also impact its trajectory. A de facto state may inherit institutional vestiges dating from the colonial period that can serve as material and ideational bases for sustained mobilization. Colonial legacy is also a powerful tool for forging a separate identity for the de facto state population, acquiring legitimacy, and attracting military support from outside actors. A colonial past has the potential to affect both the degree of state building in the de facto state and the extent of military support separatists get from third parties—two key factors that, in turn, are expected to lower the likelihood of reintegration.

Additionally, I control for the presence of Peacekeepers on the territory of the de facto state20 and for the number of countries that officially recognize a de facto state in any given year (Recognition). Prior scholarship suggests that while peacekeepers may prevent conflict recurrence, their presence can also reinforce the status quo (Fortna 2008). By determining which units are legitimized as states, recognition functions as a powerful selection mechanism that can influence a polity’s survival prospects. Fazal (2007, 83) finds that international recognition strongly influences unit longevity: the more recognition a would-be state receives, the greater its chances of survival. Shelef and Zeira (forthcoming, 3) argue that recognition increases the appetite for secession and decreases support for a negotiated compromise. There is large variability in recognition patterns for de facto states: some (like Somaliland) lack any kind of recognition or are recognized only by a patron state (like Northern Cyprus), while others receive recognition from many countries (for example, Western Sahara—recognized by 48 countries at the end of 2011). Nonrecognition reduces de facto states’ long-term viability, as it prevents them from enjoying key benefits of statehood (Coggins 2011, 448). Membership in the club of recognized states confers not only legal privileges but also more tangible gains such as access to international trade, investment, loans, and arms purchases that enable countries to boost their military wherewithal (Fazal and Griffiths 2014). A country’s decision to recognize (or withdraw recognition from) a de facto state is rarely based on legal principles, but is primarily driven by strategic objectives.21 Regardless of countries’ reasons for supporting a de facto state’s independence, recognition is essential because it signals support for separatists’ aspirations at both the domestic and international level. Domestically, countries that recognize a de facto state often provide assistance that bolsters rebels’ military arsenal and governance activities. For example, after Algeria recognized the independence of Western Sahara on March 6, 1976, it immediately offered extensive military and political support that has allowed the de facto state to survive to this day. Internationally, even limited recognition confers legitimacy to separatists’ independence aspirations, and imparts a veneer of statehood (Ker-Lindsay 2012).

Estimation Procedure

To assess the relationship between variables and de facto state outcomes, I estimate a series of competing risks hazard models. Competing risks refer to the probability of any type of de facto state disappearance relative to the probability of de facto state survival. Competing risks assess the relationship between covariates and the disappearance rate or the corresponding probability of any one of the possible types of de facto state outcomes allowing for competing risks from the other types of outcomes.22 These models estimate cause-specific hazards; hence, the effect of covariates may be different for each type of de facto state disappearance.

Competing risks models compute sub-hazards—cause-specific hazards for the outcome of interest as well as for the other possible, or “competing,” outcomes. The sub-hazard for outcome i at time t gives the instantaneous probability for a de facto state to experience outcome i given that it has survived up to time t and that all types of outcomes are possible. Sub-hazards have a similar interpretation to hazard ratios, where values greater than 1 indicate a higher likelihood of an outcome and values lower than 1 a lower probability of an outcome. The conventional approach to analyzing competing risks data is to run a Cox model for each event separately—in this case, for each type of de facto state disappearance—while the other “competing” types are censored.23

Results and Discussion

Table 2 presents the results of the competing risks models, one for each type of de facto state outcome.24Table 3 summarizes the substantive effect of key variables on outcomes.

De facto state outcomes

| . | (1) Forceful reintegration . | (2) Peaceful reintegration . | (3) Statehood . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prior status | 1.234(1.103) | 0.515(0.639) | |

| Colony | 0.860(1.250) | 0.243(0.316) | |

| Peacekeepers | 3.072(4.477) | 7.125(11.328) | 7.430** (6.653) |

| Recognition | 0.998**(0.001) | ||

| Military support | 0.995(0.003) | 0.990*(0.005) | 0.986*** (0.003) |

| State building | 0.997(0.002) | 0.997**(0.001) | 1.015***(0.005) |

| Fragmentation | 1.003(0.002) | 0.986**(0.006) | 1.002*** (0.001) |

| Veto players | 1.001(0.002) | 1.005**(0.002) | 0.993*** (0.002) |

| Subjects | 34 | 34 | 34 |

| Failures | 6 | 6 | 4 |

| N | 780 | 780 | 780 |

| . | (1) Forceful reintegration . | (2) Peaceful reintegration . | (3) Statehood . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prior status | 1.234(1.103) | 0.515(0.639) | |

| Colony | 0.860(1.250) | 0.243(0.316) | |

| Peacekeepers | 3.072(4.477) | 7.125(11.328) | 7.430** (6.653) |

| Recognition | 0.998**(0.001) | ||

| Military support | 0.995(0.003) | 0.990*(0.005) | 0.986*** (0.003) |

| State building | 0.997(0.002) | 0.997**(0.001) | 1.015***(0.005) |

| Fragmentation | 1.003(0.002) | 0.986**(0.006) | 1.002*** (0.001) |

| Veto players | 1.001(0.002) | 1.005**(0.002) | 0.993*** (0.002) |

| Subjects | 34 | 34 | 34 |

| Failures | 6 | 6 | 4 |

| N | 780 | 780 | 780 |

Hazard ratios are reported with robust standard errors clustered by de facto state.

p<.10

p<.05

p<.01.

De facto state outcomes

| . | (1) Forceful reintegration . | (2) Peaceful reintegration . | (3) Statehood . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prior status | 1.234(1.103) | 0.515(0.639) | |

| Colony | 0.860(1.250) | 0.243(0.316) | |

| Peacekeepers | 3.072(4.477) | 7.125(11.328) | 7.430** (6.653) |

| Recognition | 0.998**(0.001) | ||

| Military support | 0.995(0.003) | 0.990*(0.005) | 0.986*** (0.003) |

| State building | 0.997(0.002) | 0.997**(0.001) | 1.015***(0.005) |

| Fragmentation | 1.003(0.002) | 0.986**(0.006) | 1.002*** (0.001) |

| Veto players | 1.001(0.002) | 1.005**(0.002) | 0.993*** (0.002) |

| Subjects | 34 | 34 | 34 |

| Failures | 6 | 6 | 4 |

| N | 780 | 780 | 780 |

| . | (1) Forceful reintegration . | (2) Peaceful reintegration . | (3) Statehood . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prior status | 1.234(1.103) | 0.515(0.639) | |

| Colony | 0.860(1.250) | 0.243(0.316) | |

| Peacekeepers | 3.072(4.477) | 7.125(11.328) | 7.430** (6.653) |

| Recognition | 0.998**(0.001) | ||

| Military support | 0.995(0.003) | 0.990*(0.005) | 0.986*** (0.003) |

| State building | 0.997(0.002) | 0.997**(0.001) | 1.015***(0.005) |

| Fragmentation | 1.003(0.002) | 0.986**(0.006) | 1.002*** (0.001) |

| Veto players | 1.001(0.002) | 1.005**(0.002) | 0.993*** (0.002) |

| Subjects | 34 | 34 | 34 |

| Failures | 6 | 6 | 4 |

| N | 780 | 780 | 780 |

Hazard ratios are reported with robust standard errors clustered by de facto state.

p<.10

p<.05

p<.01.

Percentage change (per year) in the hazard of each de facto state outcome

| Recognition . | Military support . | State building . | Fragmentation . | Veto players . | De facto state outcome . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| –0.2% | insig. | insig. | insig. | insig. | Forceful reintegration |

| n.e. | –1.0% | –0.3% | –1.4% | +0.5% | Peaceful reintegration |

| n.e. | –1.4% | +1.5% | +0.2% | –0.7% | Statehood |

| Recognition . | Military support . | State building . | Fragmentation . | Veto players . | De facto state outcome . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| –0.2% | insig. | insig. | insig. | insig. | Forceful reintegration |

| n.e. | –1.0% | –0.3% | –1.4% | +0.5% | Peaceful reintegration |

| n.e. | –1.4% | +1.5% | +0.2% | –0.7% | Statehood |

Results significant at the .10 level or above.

insig. = effect is statistically insignificant.

n.e. = not estimated (outcome perfectly predicted or insufficient variation).

Percentage change (per year) in the hazard of each de facto state outcome

| Recognition . | Military support . | State building . | Fragmentation . | Veto players . | De facto state outcome . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| –0.2% | insig. | insig. | insig. | insig. | Forceful reintegration |

| n.e. | –1.0% | –0.3% | –1.4% | +0.5% | Peaceful reintegration |

| n.e. | –1.4% | +1.5% | +0.2% | –0.7% | Statehood |

| Recognition . | Military support . | State building . | Fragmentation . | Veto players . | De facto state outcome . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| –0.2% | insig. | insig. | insig. | insig. | Forceful reintegration |

| n.e. | –1.0% | –0.3% | –1.4% | +0.5% | Peaceful reintegration |

| n.e. | –1.4% | +1.5% | +0.2% | –0.7% | Statehood |

Results significant at the .10 level or above.

insig. = effect is statistically insignificant.

n.e. = not estimated (outcome perfectly predicted or insufficient variation).

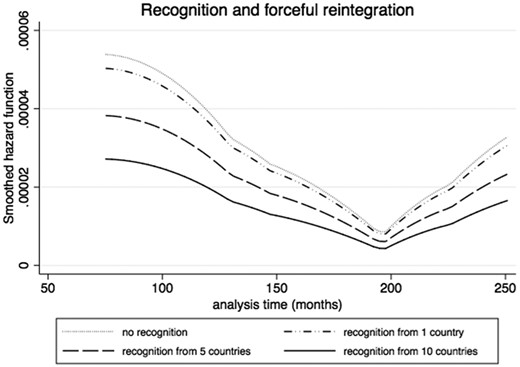

The results are supportive of some propositions and less so of others. Model 1 explores the forceful reintegration outcome. The covariates fail to achieve standard levels of statistical significance, with one exception: recognition. The hazard ratio is 0.998, showing that international recognition decreases the risk of forceful reintegration by roughly 0.2 percent per year. Recognition from UN member countries may not single-handedly offer a de facto state an entry pass into the international community, but may provide a ticket for survival. To get a better sense of the effect of recognition on the likelihood of a de facto state’s forceful reintegration, Figure 1 plots (smoothed) hazard estimates for forceful reintegration at different values for the recognition covariate. As we can see from the graph, the likelihood of forceful reintegration seems to be lower for those de facto states that manage to secure recognition from a larger number of countries. This pattern is noteworthy because it provides cross-case validation of small-N works that regard recognition as a critical ingredient for the long-term viability of de facto states (Caspersen 2012; Kingston and Spears 2004; Lynch 2004).

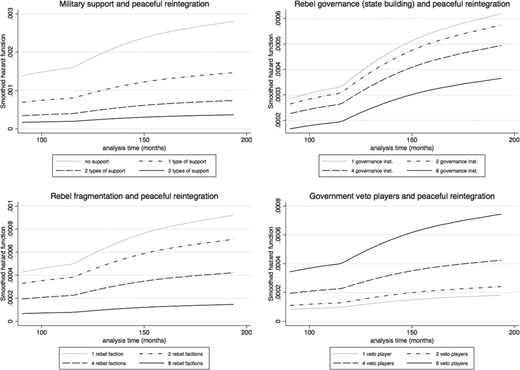

The results under Model 2 focus on peaceful reintegration and reveal multiple trends. The theory postulated that rebels have few rational incentives to sign on to an agreement with the government when they benefit from external military assistance (H1). The findings corroborate this expectation: the hazard ratio for the Military Support variable is 0.990, showing that each additional type of external support lowers the risk of peaceful reintegration by about 1 percent per year. This result lends credence to accounts that hold that separatists have few incentives to commit to an agreement with the parent state when they benefit from a constant flow of military assistance (Jenne 2007, 12). Figure 2 offers a window into how important external support is for the prospect of peaceful reintegration. As depicted in the graph, each additional type of outside assistance substantially reduces the likelihood of peaceful reintegration such that the probability of a negotiated deal for those de facto states that receive extensive military support (three or more types of support) is close to 0. The message here is straightforward: as long as separatist enclaves such as Transnistria or South Ossetia continue to be backed up by external patrons, the chances for a negotiated agreement remain slim, if not inexistent.

The effect of military support, rebel governance, rebel fragmentation, and government veto players on the likelihood of peaceful reintegration

The results also support the expectation that rebel state building lowers the prospects for peaceful reintegration (H2). For each type of governance activity rebels engage in, the probability of a negotiated solution decreases by 0.3 percent per year. Rebel governance is costly, and signals long-term commitment to separate rule. The institutionalization of alternate structures of governance seems to shape separatists’ preferences away from autonomy arrangements. Figure 2 reveals that the more sophisticated the governance apparatus established by separatists, the lower the likelihood of an autonomy deal. Where rebels establish complex architectures of separate rule, the chances of peaceful reintegration are minimal. The third hypothesis (H3) anticipated that fragmented de facto states are less likely to be peacefully reintegrated. The result for rebel movement fragmentation under Model 2 seems to support this conjecture. The hazard is 0.986, indicating that an additional faction in the rebel movement reduces the risk of a negotiated deal by 1.4 percent per year. This finding falls squarely in line with the literature that stresses the commitment problems posed by an internally divided insurgency. Rebel leaders presiding over a fragmented movement have greater difficulty committing to an agreement with the government in the presence of splinter groups that might renege on the deal and continue the self-determination struggle. As shown in Figure 2, extremely fractionalized de facto states are unlikely to reach autonomy deals with the government. Where separatist enclaves encompass 8 or more factions, the probability of a peaceful settlement is close to 0. Hence, it should come as no surprise that many resilient de facto states, like Palestine or Republika Srpska, are among the most fragmented in the population.

As for the impact of government veto players, Model 2 suggests a relationship that runs contrary to the hypothesized one (H4). The hazard stands at 1.005, indicating that an additional veto player increases the risk of peaceful reintegration by about 0.5 percent per year. Recent work by Cunningham (2014) and Sorens (2012) helps us elucidate this apparently counterintuitive finding. Both authors posit that governments with a moderate number of veto players are better positioned to reach deals with self-determination groups because they make for more credible bargaining partners. Some level of division within the parent state enhances its credibility as a bargaining partner because the executive cannot unilaterally renege on concessions made to the rebels (Cunningham 2014, 75; Sorens 2012, 123). More generally, Gehlbach and Malesky (2010) demonstrate that contrary to conventional wisdom, the presence of multiple veto players might actually encourage policy change. The rationale behind this reasoning holds that a high number of veto players can weaken the power of those actors who prefer the status quo (Gehlbach and Malesky 2010, 957). The result for the effect of veto players on a de facto state’s peaceful reintegration prospects needs also to be understood in light of the proxy used to measure internal divisions within parent states, Polity IV’s “executive constraints” variable. This covariate can be interpreted to capture regime type (democracies typically exhibit a larger number of institutional veto points than autocracies, and are more effective at making credible commitments) or institutional variation across regime types (democracies, hybrid regimes, and autocracies display variability in the number of veto points). Since de facto states have endured in democracies (for example, TRNC in Cyprus), semi-democracies (for example, Chechnya in Russia during the 1990s), and dictatorships (for example, the Karen State in Burma/Myanmar), it appears that the veto player proxy reflects the degree of institutional variation across regime types: it captures constraints on executive decision-making across democracies and non-democracies alike. Hence, the veto player result suggests that those parent state leaders who are more constrained in their decision-making process, regardless of regime type, are better situated to credibly commit to a peaceful agreement with separatists in a de facto state.25

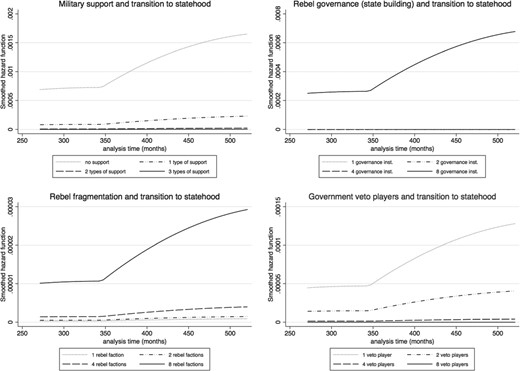

Model 3 presents the results for de facto states’ transition to statehood. Overall, the findings are congruent with the theoretical expectations. The evidence suggests that those de facto states that benefit from external military support are less likely to join the community of internationally recognized states (H1). The hazard for this variable is 0.986, indicating that each additional type of outside military assistance reduces the risk of transition to statehood by approximately 1.4 percent per year. In Figure 3, we notice that the probability of independence for a de facto state that receives substantial military assistance from third parties stands at 0. The chance of independence increases when a separatist enclave receives little or no military aid. External support may indeed be a blessing for a de facto state’s survival, but the evidence presented herein suggests it is a curse for its independence aspirations. As the cases of Eritrea and South Sudan show, those de facto states that operate autonomously stand a better chance of being welcomed into the community of states than those which function under the protection of an external patron.

The effect of military support, rebel governance, rebel fragmentation, and government veto players on the likelihood of transition to statehood

As expected, state building emerges as a strong predictor of a de facto state’s transition to statehood (H2). The hazard is 1.015, suggesting that an additional type of governance structure established by separatists increases the chance of independence by 1.5 percent per year. Figure 3 highlights the importance of rebel governance for de facto states’ independence prospects. Those breakaway entities displaying 4 or fewer governance institutions have virtually no chance of joining the international community. The statehood prospects rise with the number of state building institutions erected by separatist rulers. The longer a de facto state manages to survive and the more statelike characteristics it acquires, the higher the likelihood of joining the international community. This is an important finding that adds to recent scholarship on governance by nonstate actors (Mampilly 2011). The result is noteworthy because it provides firsthand evidence of systematic effects of rebel governance on institutional outcomes in internal conflicts. The empirical pattern suggests that in the long run, building statelike structures augurs well for separatists’ independence aspirations. By replicating the state machinery, de facto state leaders accrue resources necessary to balance militarily against the government, generate civilian support, and gain legitimacy. In fact, by acting like a “real” country, de facto states may have some chance of eventually becoming one. Additionally, Model 3 provides support for the idea that the presence of international peacekeepers solidifies an enclave’s separation and might, eventually, pave the way for its independence.

When looking at the result for rebel fragmentation, it appears inconsistent with the theoretical expectation that fractionalized de facto states are less likely to make the transition to statehood (H3). The hazard for this variable is 1.002, showing that an additional faction in the rebel movement increases the chance of independence by 0.2 percent per year. Figure 3 reveals that extremely divided de facto states exhibit a higher probability of making the transition to statehood. This finding warrants further investigation. Speculatively, one might conjecture that splintering could represent an early indicator of political competitiveness and subsequent democratization in the post-independence environment (Huang 2012). Another plausible mechanism suggests that while factions may complicate commitment in the short term, they can also make long-term enforcement easier (Driscoll 2012). Finally, the results under Model 3 validate the claim that government veto players can prevent a de facto state’s independence (H4). The hazard for this covariate stands at 0.993, indicating that an additional veto player reduces the chance of transition to statehood by approximately 0.7 percent per year. When institutional divisions abound and multiple players have veto power, governments cannot commit to recognize the independence of a separatist enclave.26

Conclusion