Article contents

Modifying U.S. Acceptance of the Compulsory Jurisdiction of the World Court

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Editorial Comments

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1985

References

1 Military and Paramilitary Activities in and against Nicaragua (Nicar. v. U.S.), Jurisdiction and Admissibility, 1984 ICJ Rep. 392 (Judgment of Nov. 26) [hereinafter cited as Nicaragua].

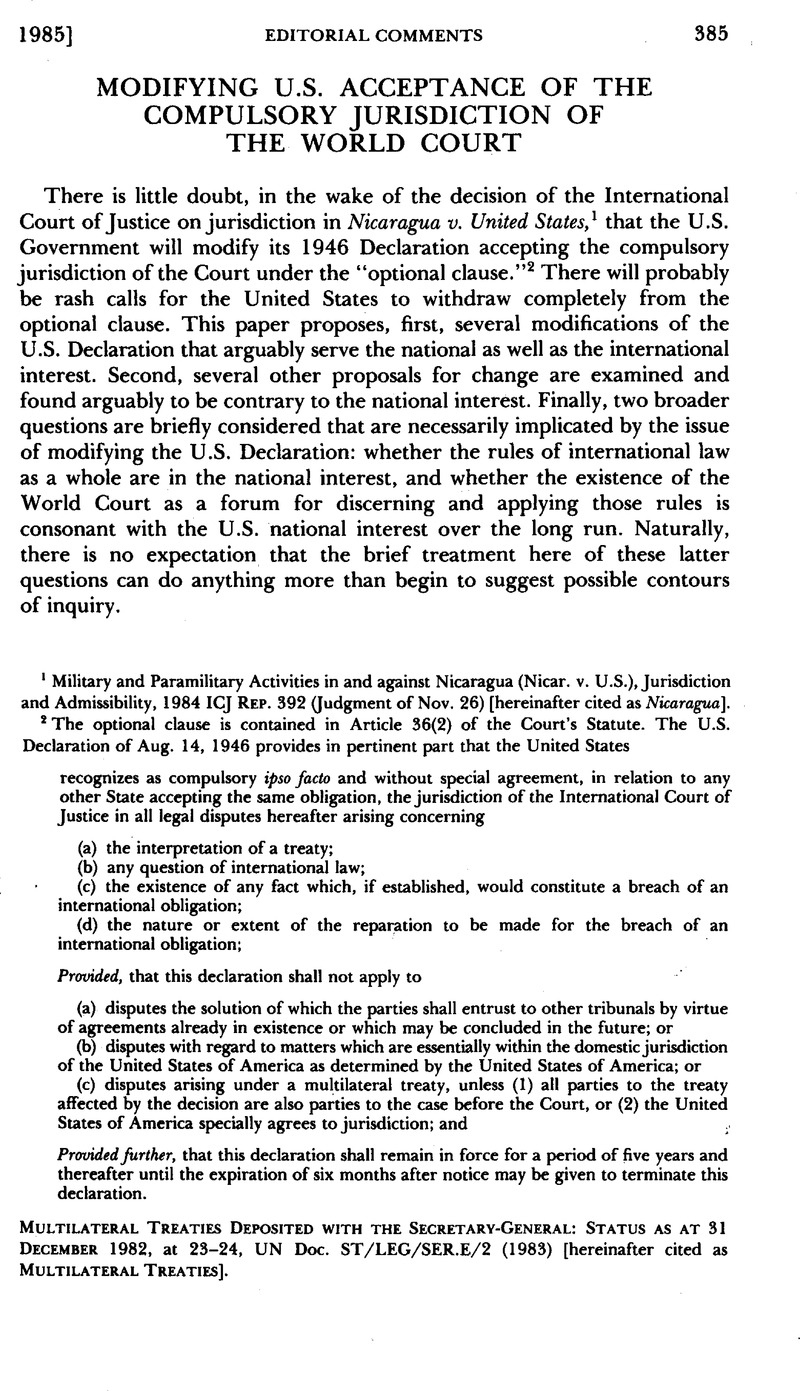

2 The optional clause is contained in Article 36(2) of the Court’s Statute. The U.S. Declaration of Aug. 14, 1946 provides in pertinent part that the United States

recognizes as compulsory ipso facto and without special agreement, in relation to any other State accepting the same obligation, the jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice in all legal disputes hereafter arising concerning

-

(a)

(a) the interpretation of a treaty;

-

(b)

(b) any question of international law;

-

(c)

(c) the existence of any fact which, if established, would constitute a breach of an international obligation;

-

(d)

(d) the nature or extent of the reparation to be made for the breach of an international obligation;

Provided, that this declaration shall not apply to

-

(a)

(a) disputes the solution of which the parties shall entrust to other tribunals by virtue of agreements already in existence or which may be concluded in the future; or

-

(b)

(b) disputes with regard to matters which are essentially within the domestic jurisdiction of the United States of America as determined by the United States of America; or

-

(c)

(c) disputes arising under a multilateral treaty, unless (1) all parties to the treaty affected by the decision are also parties to the case before the Court, or (2) the United States of America specially agrees to jurisdiction; and.

Provided further, that this declaration shall remain in force for a period of five years and thereafter until the expiration of six months after notice may be given to terminate this declaration.

Multilateral Treaties Deposited with the Secretary-General: Status as at 31 December 1982, at 23-24, UN Doc. ST/LEG/SER.E/2 (1983) [hereinafter cited as Multilateral Treaties].

3 United States Diplomatic and Consular Staff in Tehran (U.S. v. Iran), 1980 ICJ Rep. 3 (Judgment of May 24). In his closing statement to the Court in support of the U.S. Application for Provisional Measures, Roberts B. Owen, the State Department’s Legal Adviser, said: “We believe that this case presents the Court with the most dramatic opportunity it has ever had to affirm the rule of law among nations and thus fulfill the world community’s expectation that the Court will act vigorously in the interest of international law and international peace.” ICJ Public Sitting, Dec. 10, 1979, Verbatim Record (uncorrected) 44 (Doc. CR 79/1, 1979), cited in Gross, , The Case Concerning United States Diplomatic and Consular Staff in Tehran: Phase of Provisional Measures 74 AJIL 395, 397 (1980)Google Scholar. Clearly an important function of the World Court is to provide a forum where a nation may state its complete legal position. In the Iranian Hostages case, “mobilizing the world community by means of the one agency of the world community most likely to speak for it in an unambiguous and authoritative way was one of the Government’s objectives.” Gordon, & Youngblood, , The Role of the International Court in the Hostages Crisis—A Rejoinder 13 Conn. L. Rev. 429, 435 (1981)Google Scholar.

4 Portugal filed its Declaration accepting the Court’s compulsory jurisdiction on Dec. 19, 1955, Multilateral Treaties, supra note 2, at 21, and 3 days later (before India was even notified of it) sued India. Case concerning Right of Passage over Indian Territory (Port. v. India) (Preliminary Objections), 1957 ICJ Rep. 125, 132 (Judgment of Nov. 26).

5 The Declaration of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, of Jan. 1, 1969, Multilateral Treaties, supra note 2, at 23, excludes disputes where the other party’s deposit or ratification of acceptance of compulsory jurisdiction occurred “less than twelve months prior to the filing of the application bringing the dispute before the Court.”

6 For a good early discussion, see Bleicher, , ICJ Jurisdiction: Some New Considerations and a Proposed American Declaration 6 Colum. J. Transnat’l L. 61, 74-75, 79-85 (1967)Google Scholar.

7 The present Egyptian Declaration is limited to legal disputes involving the Suez Canal.

8 Declaration of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, supra note 5.

9 Nottebohm case (Liechtenstein v. Guat.) (Preliminary Objection), 1953 ICJ Rep. 111, 123 (Judgment of Nov. 18).

10 Nicaragua, para. 62. To be sure, this holding is somewhat complicated by the fact that the United States in that case claimed that Nicaragua’s Declaration, which did not specify its duration, was capable of immediate termination without notice, and hence that, reciprocally, the U.S. 6-month notice provision should not apply against Nicaragua; rather, on the principle of reciprocity, the United States arguably should be able to terminate its own Declaration vis-à-vis Nicaragua immediately and without notice. Part of the trouble with this argument was the fact that the Nicaraguan Declaration contained no language that the United States could use and cite; immediate terminability was not something that Nicaragua had expressly included in its own Declaration. But this would be a slender distinction for the United States to count on in the future against a nation, like Canada, that provides for immediate termination upon notice to the United Nations. (The Declaration of Canada of Apr. 7, 1970, Multilateral Treaties, supra note 2, at 13, provides that the Canadian Government “reserves the right at any time, by means of a notification addressed to the Secretary-General of the United Nations, and with effect as from the moment of such notification, either to add to, amend or withdraw any of the foregoing reservations, or any that may hereafter be added.”) In that case, the Court is more likely to elevate the sentence just quoted in the text into an unshakable rule, excluding from the operation of reciprocity matters relating to the formal conditions of the duration or modification of declarations of acceptance of jurisdiction.

11 See note 9 supra.

12 Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Egypt, Gambia, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua, Nigeria, Panama, Uganda and Uruguay.

13 Australia, Austria, Barbados, Belgium, Botswana, Canada, Costa Rica, Kampuchea, El Salvador, India, Israel, Japan, Kenya, Liberia, Malawi, Malta, Mauritius, Pakistan, the Philippines, Portugal, Somalia, Sudan, Swaziland, Togo and the United Kingdom.

14 Only ten states would be left, those which, like the United States, have a notice-of-withdrawal provision of 6 months or longer. They are Denmark, Finland, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden and Switzerland.

15 S. Rep. No. 1835, 79th Cong., 2d Sess. 1, 5 (1946). Unfortunately, withdrawal in the face of a threatened lawsuit seems to be precisely what the U.S. Government attempted to do on Apr. 6, 1984, when the Secretary of State notified the Secretary-General of the United Nations that the U.S. Declaration “shall not apply to disputes with any Central American state” for a period of 2 years. Three days later, Nicaragua filed its Application in the World Court against the United States. In its Judgment on jurisdiction, the Court held that the United States could not abrogate the 6-month notice provision of its 1946 Declaration. By participating in the case and by arguing vigorously, the United States went a long way toward countering the unfavorable legal image evoked by the attempted withdrawal of April 6.

16 Nicaragua, para. 113. In addition to Judge Schwebel’s dissenting vote, Judges Oda and Jennings, concurring, would have upheld the validity of the withdrawal on Apr. 6, 1984 on the ground that Nicaragua’s Declaration was theoretically terminable with no notice and hence temporal reciprocity should be applied in favor of the United States. Id., 1984 ICJ Rep. at 510-13, 546-50 (Oda, J., and Jennings, J., concurring, respectively). Judge Schwebel, it should be added, acknowledged strong reasons against the validity of the April 6 withdrawal. See id. at 617-18 (Schwebel, J., dissenting).

17 The Court’s interpretation of a 3-day period as not constituting a reasonable period of time was undoubtedly made easier by the fact that the Nicaraguan Declaration says nothing about withdrawal or termination; hence, by “operation of law” it can be said that a reasonable time should be read into it. The situation would be made more difficult for the Court if it had to construe one of the several declarations that provide expressly for withdrawal to take place from the moment of notification. However, having once determined that 3 days is not a reasonable time, the Court may find it possible, when later confronted with a declaration providing for withdrawal from the “moment” of notification, to say that although withdrawal takes effect as of the moment of notification, the notification process itself must consume a reasonable period of time after preliminary notice is given to other states that the notification process has begun.

18 Further, to attempt to lock in reciprocity, the United States might want to specify that it may only be sued by states whose declarations provide for a 6-month notice of modification or termination, and if the language of the declarations is not clear on this point, then the Court itself must, as a preliminary matter, determine the amount of time to be inferred from those declarations. If the Court fails to determine the meaning, or if the Court does so but determines the meaning as allowing for less than 6 months’ notice, then the United States does not consent to being sued by those states. Nevertheless, for the reasons given in the text, this approach, too, may turn out to be too draconian.

19 See the references cited in Crawford, , The Legal Effect of Automatic Reservations to the Jurisdiction of the International Court 50 Brit. Y.B. Int’l L. 63, 63 n.3 (1979)Google Scholar.

20 42 Dep’t St. Bull. 111, 118 (1960).

21 See Statement by Secretary Herter, id. at 227

22 Case of Certain Norwegian Loans (Fr. v. Nor.), 1957 ICJ Rep. 9, 27 (Judgment of July 6).

23 Dissenting in the Interhandel Case (Switz. v. U.S.), 1959 ICJ Rep. 6, 95, 101-02 (Judgment of Mar. 21), Judge Lauterpacht stated that the Connally reservation,

being an essential part of the [U.S.] Declaration of Acceptance, cannot be separated from it so as to remove from the Declaration the vitiating element of inconsistency with the [ICJ] Statute and of the absence of a legal obligation. The Government of the United States, not having in law become a party, through the purported Declaration of Acceptance, to the system of the Optional Clause of Article 36(2) of the Statute, cannot invoke it as an applicant; neither can it be cited before the Court as defendant by reference to its Declaration of Acceptance.

24 See D’Amato, Domestic Jurisdiction, in Encyclopedia of Public International Law (Instalment 10).

25 Nicaragua, paras. 72, 75. The Court cogently posited the hypothetical that “if the Court were to decide to reject the Application of Nicaragua on the facts, there would be no third State’s claim to be affected.” Id., para. 75.

26 Undoubtedly, the U.S. Government has considered going to the World Court with respect to numerous foreign policy incidents over the years, but of course it is hard to know how close these possibilities came to fruition, and for what reasons. One situation that did surface, however, occurred in 1955 when the United States sued Bulgaria. Case concerning the Aerial Incident of 27 July 1955 (U.S. v. Bulgaria), 1960 ICJ Rep. 146 (Order of May 30), in which the United States discontinued proceedings in the case when it became evident that Bulgaria proposed to exercise its right to invoke the Connally reservation on a reciprocal basis. Another example that ended at the diplomatic level occurred in the 1960s when the United States threatened Canada with referring various maritime disputes to the World Court. Canada replied that in that event it would invoke the Connally Amendment.

27 Declaration of Canada, Apr. 7, 1970, supra note 10.

28 (FRG v. Den.; FRG v. Neth.), 1969 ICJ Rep. 3 (Judgment of Feb. 20). For an analysis of this case regarding the line between general and special custom, see D’Amato, , The Concept of Human Rights in International Law 82 Colum. L. Rev. 1110, 1140-44 (1982)Google Scholar.

29 Declaration of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Feb. 28, 1940, League of Nations O.J. Spec. Supp. 193, at 39 (1944).

30 The list is taken largely from the Draft General Treaty on the Peaceful Settlement of International Disputes, Art. 29, prepared for the American Bar Association by Professor Louis B. Sohn, July 1983.

31 See D’Amato, , Is International Law Really “Law”? 80 Nw. L. Rev. (1985)Google Scholar.

32 Nevertheless, the transboundary force rule may be permeable. For an argument that Article 2(4) was not violated by Israel’s use of transboundary military force against a nuclear reactor in the territory of Iraq, see D’Amato, , Israel’s Air Strike upon the Iraqi Nuclear Reactor 77 AJIL 584 (1983)CrossRefGoogle Scholar. See also infra note 35.

33 The customary practice underlying Article 2(4) of the UN Charter already has shifted and changed the meaning of its terms, transforming the treaty rule into a rule of customary law that more accurately reflects the competing needs of states. See, e.g., Franck, , Who Killed Article 2(4)? 64 AJIL 809 (1970)Google Scholar.

34 See Rovine, , The National Interest and the World Court in 1 The Future of the International Court of Justice 313 (Gross, L. ed. 1976)Google Scholar.

35 Many readers will probably dispute the argument made here. They will point to statements by the Court in its opinion that the U.S. military incursion was not an issue before the Court or that it amounted at worst to a disrespect for the Court’s adjudicatory procedures in an ongoing case. But what the Court did is more important than what it said. It adjudicated all the legal issues in the case, concluded that Iran owed reparations to the United States, and despite Judge Morozov’s pointed reference to the matter in dissent, provided no offset in any amount for the damage or even nominal insult to Iran’s territory occasioned by the American incursion. For a full statement of this argument, see D’Amato, supra note 28, at 1152-54.

36 See generally L. Gross (ed.), supra note 34.

37 Moynihan, , International Law and International Order 11 Syracuse J. Int’l L. & Com. 1, 8 (1984)Google Scholar.

* Portions of this paper are based on an address given by the author to the John Bassett Moore Society of International Law at the University of Virginia School of Law, Nov. 16, 1984. The author would like to thank Professor Louis B. Sohn, Professor Edward Gordon and Dr. Paul C. Szasz for their helpful comments.

- 5

- Cited by