Abstract

Predatory publishing represents a major challenge to scholarly communication. This paper maps the infiltration of journals suspected of predatory practices into the citation database Scopus and examines cross-country differences in the propensity of scholars to publish in such journals. Using the names of “potential, possible, or probable” predatory journals and publishers on Beall’s lists, we derived the ISSNs of 3,293 journals from Ulrichsweb and searched Scopus with them. 324 of journals that appear both in Beall’s lists and Scopus with 164 thousand articles published over 2015–2017 were identified. Analysis of data for 172 countries in 4 fields of research indicates that there is a remarkable heterogeneity. In the most affected countries, including Kazakhstan and Indonesia, around 17% of articles fall into the predatory category, while some other countries have no predatory articles whatsoever. Countries with large research sectors at the medium level of economic development, especially in Asia and North Africa, tend to be most susceptible to predatory publishing. Arab, oil-rich and/or eastern countries also appear to be particularly vulnerable. Policymakers and stakeholders in these and other developing countries need to pay more attention to the quality of research evaluation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

“Predatory” (or fraudulent) scholarly journals exploit a paid open-access publication model: the publisher does not charge subscription fees, but receives money directly from the author of an article that becomes accessible for free to anyone. However, this entails a conflict of interests that has the potential to undermine the credibility of open-access scholarly publishing (Beall 2013). Authors are motivated to pay to have their work published for the sake of career progression or research evaluation, for instance (Bagues et al. 2019; Kurt 2018; Demir 2018). In return, predatory publishers turn a blind eye to any limitations of papers during peer-review in favor of generating income from authors' fees; the worst of them fake the peer-review process and print almost anything for money, without scruples (Bohannon 2013; Butler 2013).

So far, only a handful of studies have examined the geographical distribution of authors published in journals suspected of predatory practices by Beall (2016). On a sample of 47 such journals, Shen and Bjork (2015) found that the authors were highly skewed to Asia and Africa, primarily India and Nigeria. Xia et al. (2015) examined 7 pharmaceutical journals and also identified the vast majority of authors as being from Southeast Asia, predominantly India, and, to a lesser extent, Africa. Demir (2018) combed through 832 predatory journals and confirmed that by far the greatest number of authors are from India, followed by Nigeria, Turkey, the United States, China and Saudi Arabia. Wallace et al. (2018) focused on 27 such journals in economics, in which the authors were most frequently from Iran, the United States, Nigeria, Malaysia and Turkey.

No matter how insightful these studies are in revealing from where contributors to predatory journals originate, we still know very little about the magnitude of the problem for the respective countries and regions. India appears to be the main hotbed of predatory publishing, but in the context of India’s gigantic research system, this may be much ado about little. All of the countries cited above are, unsurprisingly, quite large. Could it be that some smaller countries are actually far worse off, though they do not stand out in the absolute figures? Just how large is the propensity to predatory publishing at the national level? Which countries are most and least affected by predatory publishing, and why?

Existing literature provides very scant evidence along these lines and the studies at hand are limited to individual countries and use different methodologies, so the results are not easily comparable. For example, Perlin (2018) found that suspected predatory journal articles accounted only for about 1.5% of publications in Brazil, while Bagues et al. (2019) showed that around 5% of researchers published in such journals in Italy. No study has yet examined the penetration of national research systems by predatory publishing in a broad comparative perspective. Systematic scrutiny of cross-country differences worldwide is lacking.

This paper helps to fill that gap by examining the propensity to publish in potentially predatory journals for 172 countries in 4 fields of research over the 2015–2017 period. Using the names of suspected predatory journals and publishers on blacklists by Beall (2016), we derived the ISSNs of 3,293 titles from Ulrichsweb (2016) and searched Scopus (2018a) for them. A total of 324 matched journals with 164 thousand indexed articles was identified. Next, we downloaded from Scopus the number of articles by author's country of origin published in these journals and compared the figures to the total number of indexed articles by country and field. The resulting database provides more representative and comprehensive country-level evidence on the problem of predatory publishing than has been available in any previous studies.

Our analysis indicates that there is remarkable heterogeneity in the propensity to publish in predatory journals across countries. In line with earlier evidence, the most affected countries are in Asia and North Africa, but they are not necessarily the same ones cited above. In the most affected countries, including Kazakhstan and Indonesia, around 17% of articles fall into the predatory category, while there are some countries with no predatory articles whatsoever. India’s situation also looks daunting, but it is not the worst off. Econometric analysis of cross-country differences shows that countries with large research sectors at the medium level of economic development tend to be most susceptible to predatory publishing. Arab, oil-rich and/or eastern countries are also particularly vulnerable. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic attempt to pin down national research systems at the most risk of falling into the trap of predatory publishing.

The paper proceeds as follows. The second section reviews existing literature on predatory publishing, introduces Beall’s lists, and elaborates on their limitations. The third section explains how the dataset has been constructed and how it can be used. The fourth section provides an exploratory analysis of differences across countries and relevant country groups. The fifth section presents econometric tests of the relationships hypothesized. The conclusionding section summarizes the key findings and pulls the strands together.

Taking stock of the literature

Predatory publishing

Jeffrey Beall popularized the term predatory publishing on his blog (Beall 2016). It is used to describe the practice of abusing paid open-access scientific publishing. In contrast to standard subscription-based models, authors publishing via paid open-access make business directly with publishing houses. They pay article processing fees directly to the publisher of the journal. Both authors and publishers are motivated to publish articles. Predatory journals perform only vague, pro-forma, and in some cases no peer-reviews, and allow publication of pseudo-scientific results (Bohannon 2013; Butler 2013). Predatory journals have also been accused of aggressive marketing practices, having fake members of editorial boards and amateur business management (Beall 2015; Cobey et al. 2018; Eriksson and Helgesson 2017a). However, these are only side-effects. We use the term predatory journals to signify journals suspected of abusing paid open-access to extort fees from authors, and following significantly flawed editorial practices.

The open-access model, though it is a defining element of predatory journals, is not at fault per se. The inherent conflict of interest does not have to be exploited. There are effective means to ensure the quality of the editorial practices of journals. Databases dedicated to supporting open-access, such as the Directory of Open Access Journals, are already working to develop operational mechanisms to guarantee quality and to employ transparency measures such as open peer-review, which can easily detect fraudulent publishers. Journals not performing peer-reviews have admittedly nothing to report here. The existence of predatory journals does not mean that the movement calling for democratizing communication of scientific results is fruitless.

Nevertheless, it is challenging to recognize a predatory journal in practice, because there is no clearly defined boundary between journals that follow ethical editorial standards and those that are merely vehicles for exploiting publication fees. Most often, to facilitate awareness and identification, black-lists are used to identify suspected predatory journals. The most prominent example is Jeffrey Beall’s blog (Beall 2016), which was shut down at the beginning of 2017 (Straumsheim 2017).Footnote 1 A private company, Cabell’s, subsequently began to offer a similar black-list (Silver 2017), but its content is locked behind a paywall. China has recently announced the formation of a blacklist of ‘poor quality’ journals (Cyranoski 2018).

The inclusion of individual journals on a black-list should be based on rigid and transparent criteria. Beall (2015) provided a list of criteria that he used to make decisions about journals and publishers. Eriksson and Helgesson (2017a) and Cobey et al. (2018) have also suggested a similar list of characteristics to identify predatory journals. The key set of Beall’s criteria points directly to the most salient problem of dubious editorial practices: (“Evidence exists showing that the publisher does not really conduct a bona fide peer-review”; “No academic information is provided regarding the editor, editorial staff, and/or review board members”). However, there is also a group of indicators concerning professionalism and/or compliance with ethical standards: (“The publisher has poorly maintained websites, including dead links, prominent misspellings and grammatical errors on the website”; “Use boastful language claiming to be a ‘leading publisher’ even though the publisher may only be a start-up or a novice organization”), etc.

Kurt (2018) identified 4 pretexts that are often used to justify publication in predatory journals: (i) social identity threat; (ii) lack of awareness; (iii) high pressure to publish; and (iv) lack of research proficiency. The common denominator is urgency. Researchers tend to publish in these journals as a last resort and often refer to institutional pressure, a lack of experience and fear of discrimination from “traditional” journals. Justifications for publishing in predatory journals is a complex mix of factors operating at both personal and institutional levels.

Demir (2018 and Baguess et al. 2019) also argue that the tendency to publish in predatory journals is likely to be related to the quality of research evaluation in the country. The more the research evaluation system relies on outdated routines such as counting articles indexed in Scopus, Web of Science or Medline regardless, the higher incentive for researchers to publish in fraudulent journals just to clinch points for outputs regardless of merit. In countries where the culture of evaluation pushes researchers to publish in respectable journals, there is little to no motivation to resort to predatory journals, as such behaviour will harm the researcher’s reputation.

Predatory publishing can be seen as wasteful of resources. Shen and Björk (2015) estimated the size of the predatory market as high as 74 million USD in 2014, based on article processing fees, and the figure may well have grown significantly since. Perhaps more important than the direct costs, however, are indirect costs stemming from the fact that the opportunity to bypass the standard peer-review process leads researchers astray. Instead of spending their time producing relevant insights, researchers may be increasingly prone to write bogus papers that only pretend to be scientific. If this occurs on an increasing scale, research systems are in peril. The fact that research published in scientific journals is predominantly funded from public sources only amplifies these concerns.

Beall’s lists

Beall (2016) maintained two regularly updated lists of “potential, possible, or probable” predatory journals and publishers, henceforth for the sake of brevity referred to as “predatory”: (i) a “list of standalone journals”, which contains individual journals suspected of predatory practices; and (ii) a “list of publishers”, which highlights questionable publishers, most of which print multiple journals.

Crawford (2014b) went through every single item on Beall’s lists (in late March and early April 2014). He found 9,219 journals in total, of which 320 were from the list of standalone journals and 8,899 from the list of publishers. Between 2012 and 2014, about 40% of those journals published no or fewer than four articles; in other words, they were empty shells, and a further 20% published only a handful of articles. Another 4% consisted of dying or dormant journals whose publications fell to a few articles in 2014, and 6% were unreachable (the web link was broken, for instance). Overall, fewer than 30% of the identified journals published articles regularly. Fewer than 5% of the journals appeared “apparently good as they stand”, meaning that there was no immediate reason to doubt their credibility, which, however, did not imply that they were in fact credible.

Shamseer et al. (2017) confirmed that Beall’s listed journals contained more spelling errors, promoted bogus bibliometric metrics on their websites and their editorial board members were much more difficult to verify than those of ‘ordinary’ journals. Bohannon (2013) exposed flawed editorial practices by submitting fake scientific articles to journals of publishers from Beall’s list. The fake articles were accepted for publication by four-fifths of the journals that completed the review process. Bagues et al. (2019) showed that journals on Beall’s list tend to have low academic impact and cite researchers admitting that editorial practices of these journals are flawed. Journals from these lists truly seem to be douftful.

Limitations

As Eriksson and Helgesson (2017b) state, “the term ‘predatory journal’ hides a wide range of scholarly publishing misconduct.” Some are truly fraudulent, while many others may operate on the margins. However, Beall’s lists force us to work with a binary classification in which a journal and publisher is considered either predatory or not. As Beall did not systematically explain his decisions, it is not possible to make a more detailed quantification of “predatoriness”, though elaborated criteria exist.

Beall’s lists have been strongly criticized for the low transparency of his decision-making process (Berger and Cirasella 2015; Crawford 2014a; Bloudoff-Indelicato 2015). Although the criteria are public, justification of decisions on individual journals and publishers is often not clear and difficult to verify. Beall debated the decissions on his blog or Twitter in some important instances, but very often a journal or publisher was added to the list without justification being provided. The lack of comprehensive, rigid, and formal justification of Beall’s judgments is a major drawback of his list.

In particular, caution is warranted when working with Beall's list of publishers. Classifying an entire publishing house as predatory is a strong judgment, and it cannot be ruled out that some journals which actually apply reputable standards have been blacklisted along the way. The list includes some publishers that maintain broad portfolios of dozens and even hundreds of journals, some of which may not deserve the predatory label, so that using Beall’s list may result in overestimations of true “predators.” It is likely that the overwhelming majority of these journals are of poor quality, but poor quality is not a crime per se. One must, therefore, keep in mind that the list of publishers has been painted with a relatively broad brush.

Nevertheless, respectable publishing houses should have zero tolerance for predatory practices. Just as in the banking sector, academic publishing services are based on trust, and if that is lost, the business is doomed. A single journal with predatory inclinations that are not quickly corrected by the publisher can substantially damage the entire brand. Beall's predatory mark signals serious doubts about the publisher's internal quality assurance mechanisms at the very least.

The greatest controversy was triggered by inclusion of the Frontiers Research Foundation on Beall’s list of publishers in October 2015. Beall defended this decision by pointing out several articles that, according to him, should not have been published. According to critics of this move, the Frontiers publisher is “legitimate and reputable and does offer proper peer-review” (Bloudoff-Indelicato 2015). Frontiers journals appear to be quite different from typical predatory outlets on the face value of their citation rates. Only 4 journals in Frontiers’ portfolio of 29 included in this study are not ranked in the first quartile in at least one field according to the Scimago SJR citation index (Scopus 2018b). Most Frontiers journals are also indexed in the Web of Science and the Directory of Open Access Journals. Hence, judging by the relevance of Frontiers journals for the scientific community, there is a question mark about their inclusion on the predatory list.

Another concern arises from the timescale. The predatory status used in this study is derived from the content of Beall's lists on 1st April 2016. Jeffrey Beall continuously updated his lists. However, the lists always reflect only current status, with no indication of when the journal and publisher may have become predatory. When looking back in time, we may run into the problem of including in the predatory category records that do not deserve that label, because the journal became predatory only a short time before its inclusion to the list. In some cases, older articles published in journals that are currently considered to be predatory may have gone through a standard peer-review. Hence, historical data must be used with great caution.

Further, Beall's lists are very likely to suffer from English bias. The lists contain mainly journals that at least have English-language websites. In regions in which a large part of scientific output is written in other languages—such as in Latin America, Francophone areas and countries of the former Soviet Union—estimates of the extent of predatory publishing based on Beall’s lists may be underestimated, because Beall did not identify predatory journals in local languages. Likewise, Scopus covers scientific literature in English far more comprehensively than publications in other major world languages. This bias should be kept in mind when interpreting cross-country differences.

Database

Our database was built in three steps. First, we compiled a comprehensive overview of journals suspected of predatory practices by matching the lists of standalone journals and publishers by Beall (2016) with records in the Ulrichsweb (2016) database, which provides comprehensive lists of periodicals. Second, we searched the International Standard Serial Numbers (ISSNs) of the journals obtained from Ulrichsweb in Scopus, and downloaded data on authors publishing in these journals by their country of origin. Third, we downloaded the total number of indexed articles by country from Scopus. Ultimately, we obtained not only a full list of predatory journals listed in Scopus but, even more importantly, we also obtainted harmonized data on the propensity to publish in these journals by country, which allows us to shed new light on cross-country patterns.

Beall's lists were downloaded on April 1st, 2016. First, we identified all search terms in each item on the lists. For some entries, Beall presented multiple versions of a journal designation; for example, the journal name and its abbreviation. All available versions were used as a search term. Next, we searched the terms in the Ulrichsweb database for the same day, using an automatic script programmed in Python. When we searched for a standalone journal, the script used the ‘title’ field, and for the publisher, the script used the ‘publisher’ field. In the end, the algorithm saved all search results. The search request in Ulrichsweb was as follows for standalone journals:

+ (+ title:("Academic Exchange Quarterly"))

and for publishers:

+ (+ publisher:("Abhinav"))

The raw search on Ulrichsweb produced a database of 19,141 results linked to individual entries on Beall’s list. Results without ISSNs were removed, as they were most probably not listed in Scopus anyway; this reduced the database to 16,037 search results with 7,568 unique ISSNs. The reduction is due to using multiple search terms related to the same entry and to the ‘fuzziness’ of the Ulrichsweb search.Footnote 2 To make sure that the journals are listed by Beall, remaining search results were checked manually. Beall's lists consist of hypertext links, so we compared the ISSN on the journal’s website with the ISSN on Ulrichsweb. If the two ISSNs matched, the entry was retained; if they differed, the entry was removed from our database. A publisher’s identity was confirmed if at least one ISSN listed on its website was found in an entry linked to the publisher's name on Ulrichsweb.

In total, we confirmed 4,665 unique ISSNs associated with Beall's lists. Many journals have dual ISSNs, one for its print and one for its electronic version. The number of individual journals is 3,293, of which 309 featured on the list of standalone journals, 2,952 referred to the list of publishers, and an additional 32 journals appeared on both lists, perhaps because Beall did not recognize that the respective journal was from a publisher already on his list. For simplicity, these journals are considered to belong to the list of publishers.

This is in line with the analysis of Crawford (2014b), which identified fewer than 3,000 journals that published articles regularly, and thus in fact appeared to be continuously in operation. Shen and Björk (2015) found around 8,000 journals that were “active” in the sense that they published at least one article. However, many of these, as per Crawford (2014b), may not publish significantly more than that and are not likely to be registered in databases. Note that there are 1,003 hypertext links on the list of standalone journals, from which it follows that more than two-thirds of these are not included in Ulrichsweb, let alone in more selective databases. Apart from the unverified information on their web pages, there is no information about them. Previous attempts to collect data on predatory journals were far less comprehensive.Footnote 3

In the next step, we searched for the presence of these “predatory” ISSNs in the Scopus (2018a) citation database over the period 2015–2017. Once again, this search was performed using an automatic script programmed in Python. The search was performed on March 19th, 2018. For each ISSN detected in Scopus, the script downloaded not only the total number of documents in the “article” category, but also more detailed data on the number of these articles by the author's country of origin. The search request in Scopus was as follows:

ISSN(1234–5678) AND DOCTYPE(ar) AND PUBYEAR > 2014 AND PUBYEAR < 2018

439 ISSNs of 324 individual journals with at least one entry in Scopus were identified, of which 37 appear on the list of standalone journals and 287 on the list of publishers. Thus, nearly 10% of the journals in our database were indexed in Scopus. In total, 164,073 articles published in these journals were detected, of which 22,235 occur in standalone journals and 141,838 come from the list of publishers, jointly making up 2.8% of all articles indexed in Scopus during the period under consideration. Hence, the list of publishers, which was rather neglected in previous empirical studies of predatory publishing, is the dominant source. The journals were assigned to four broad fields of research: (i) Health Sciences; (ii) Life Sciences; (iii) Physical Sciences; and (iv) Social Sciences, based on the Scopus Source List (Scopus 2018b). If a journal is assigned to multiple fields, it is fully counted in each of them. The database is available for download as supplementary information for this paper.

Finally, we obtained data on the total number of articles in Scopus by author's country of origin and field of research over the period 2015–2017, which is the denominator required to compute the penetration of predatory journals in the article output of each country. The download was performed on March 5th, 2020. The search was performed using the following request:

AFFILCOUNTRY(country) AND SUBJAREA (field) AND DOCTYPE (ar) AND PUBYEAR > 2014 AND PUBYEAR < 2018

In the Scopus database, an article is fully attributed to a country if affiliation of at least one of its authors is located in that country. Joint articles by authors from different countries are counted repeatedly in each participating country. Hence, the data measure article counts, not fractional assignments. If articles in predatory journals have fewer co-authors than other articles, the predatory articles penetration is underestimated and vice-a-versa; this can be uneven across countries.Footnote 4 For some articles, Scopus reports the country of origin as “undefined”; these are excluded from our analysis.Footnote 5

Admittedly, predatory journals that are indexed in Scopus represent only the tip of the iceberg, which is not representative of the whole business. Since journals must fulfil a number of selection criteria prior to acceptance into the database (Scopus 2019), no matter how imperfect the filter turns out to be, this is probably the least ugly part. However, from the research evaluation perspective, predatory journals indexed in respected citation databases are more dangerous than ordinary bogus journals that few take seriously, because the indexation bestows a badge of quality.Footnote 6 All too often, evaluations at various levels rely on this badge and blindly assume that whatever is indexed counts. Scopus-listed journals are in practice considered ‘scientific’ by many institutions and even national evaluation systems, such as, for example, in the Czech Republic (Good et al. 2015), Italy (Bagues et al. 2019) and probably many developing countries. In particular, evaluation systems that do not check the actual content using their own peer-review assessment are most exposed, but such assessment tends to be expensive and difficult to organize, and thus is relatively rare exactly in environments that need this check most (Table 1).

Cross-country patterns

Out of more than two hundred countries for which the data are available, we excluded dependent territories and countries with fewer than 300,000 inhabitants. The analysis considers evidence from the period between 2015 and 2017, because, as noted above, using older data risks that some of the journals currently featurted on Beall's lists were not yet predatory at an earlier time. However, we use data from three years to increase the robustness of the results. Only countries generating at least 30 articles during this period are included in the analysis. As a result, the final sample consists of 172 countries, which together account for the overwhelming majority of the world's research activity.

The outcome variable used throughout the analysis is the share of articles linked to Beall’s lists out of all articles by authors from the given country, hence the share of articles published in predatory journals out of total articles. First, we look at the global picture and examine which countries are most and least affected by predatory publishing. Then, we attempt to pin down the most salient patterns by considering differences between groups of countries. Finally, we investigate how these patterns differ by broad fields of research.

Figure 1 displays the results on a world map. The darker the colour, the higher the national propensity to publish in predatory journals. The main pattern is visible at a quick glance; the darkest areas are concentrated in Asia and North Africa. In contrast, Europe, North and South America and Sub-Saharan Africa are relatively pale. Hence, generally speaking, both the most and least developed countries tend to be relatively less affected, while developing countries with emerging research systems, excepting those in South America, appear to be most in harm’s way.

Table 2 shows figures for the top and bottom 20 countries. Kazakhstan and Indonesia appear to be the most dire, with roughly every sixth article falling into the predatory category. They are followed by Iraq, Albania and Malaysia, with more than every tenth article appearing in predatory journals. Some of the most severely affected countries are also among the largest in terms of population: India, Indonesia, Nigeria, the Philippines and Egypt, which underlines gravity of the problem. However, small countries that might have been difficult to spot on a world map, such as Albania, Oman, Jordan, Palestine and Tajikistan are also seriously affected. South Korea is by far the worst among advanced countries. All countries on the top 20 list, excepting only Albania, are indeed in or very near Asia and North Africa.

Surprisingly, the opposite end of the spectrum, with the lowest penetration of predatory journal articles, is also dominated by developing countries, including some of even the least developed. In several, for instance Bhutan, Chad and North Korea, there are no authors published in predatory journals whatsoever. This is a rather diverse group of countries scattered across continents. Nevertheless, they have one additional feature in common: most are small countries with underdeveloped research systems. In fact, 13 countries on the bottom 20 list produced fewer than 100 articles per year, on average. It may well be that these research systems are small enough to make direct oversight of the actual content of the manuscripts feasible, in which case, predatory journal articles would have nowhere to hide. In large research systems with thousands of articles produced every year, predatory publishing may more easily fly under the radar of the relevant principals.

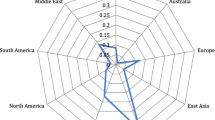

Table 3 summarizes the main patterns by presenting average propensities to publish in predatory journals by country groups, and provides details by the source list. First, we reiterate the geographical dimension by continents, which confirms that the epicentre of predatory publication is in Asia, while the problem is relatively limited in North and South America. In fact, Suriname, the most affected country in the latter, only ranks 50th in a worldwide comparison. On average, Europe and Africa fall in between the two extremes, but this masks relatively large national differences within these continents along the east–west and north–south axes, respectively. Oceania is also little involved, but there are few countries in the region.Footnote 7

Next, we examine differences by major language zones using indicators obtained from the GeoDist database which measure whether the language (mother tongue, lingua francas or a second language) is spoken by at least 20% of the population of the country (Mayer and Zignago 2011). Only English, French, Spanish and Arabic are recognized separately, as other languages are not spoken in a sufficient number of countries. Note that, in contrast to geography, assignment to language zones is not mutually exclusive, as more than one language can be frequently spoken in the same country.Footnote 8

Admittedly, language zones partly overlap with geography. This is most apparent in South America, which is dominated by Spanish-speaking countries and thus, not surprisingly, the propensities are very similar in both country groups. More revealing is perhaps the fact that Arabic-speaking countries, which are concentrated in North Africa and the Middle East, are the primary hotbeds of predatory publishing. English- and French-speaking countries are far more geographically scattered across the globe.

As noted above, Beall’s lists may suffer from English bias. Nevertheless, our results only partially support this expectation. English-speaking countries do not display significantly higher propensities towards predatory publishing than Francophone areas or countries speaking other languages. Spanish-speaking countries turn out to be different, perhaps because we miss predatory journals published in Spanish by relying on Beall’s lists and/or Scopus data, but speaking English specifically does not make much difference. Of course, more scholars speak English than do general populations, so tentatively the key take away from these figures should be that, for the most part, language does not seem to be a serious entry barrier into predatory publications.

Language zones, in turn, reflect broader differences related to religion, culture and history, including past colonial links, which often translate to shared institutions and principles of governance. Arabic countries are likely to appear, on average, highly prone to predatory publishing due to a bundle of these factors that affect how research is organized, evaluated and funded far more than the language itself has an impact. In any case, the language zones are a handy tool to account for broad differences along these lines, especially because such data is available for a very large sample of countries.

Third, it is notable that the top 20 list includes oil-rich countries such as Brunei, Iraq, Kazakhstan, Libya, Nigeria and Oman, and a closer look at the data reveals that a few more, including Algeria, Bahrain, Iran, Russia and Saudi Arabia, line up just short of the top 20. To check whether this is a systematic pattern, we draw on indicators for rents from natural resources in the World Development Indicators database (World Bank 2018), specifically from oil and natural gas, and also for a comparison of rents from other resources, including coal, minerals and forests. Countries are classified as intensive on the respective resources if their resource rents constitute more than 5% of GDP; this may sound low, but in practice constitutes a healthy boost to the government budget.

The results confirm that countries with an economy intensive on rents from oil and natural gas are on average noticeably more susceptible to predatory publishing than the rest of the world. Moreover, interestingly, this seems to be specific to oil and natural gas, as countries rich in other types of natural resources display even less tendency to predatory publishing than countries which are not particularly endowed by any of the natural resources considered here. It may not be coincidental that some of the oil-rich countries, particularly in the Middle East, began to invest their resource windfalls in indigenous university sectors, while lacking a strong research evaluation culture, which takes time to develop.

Fourth, we examine whether there are differences along the level of economic development. For this purpose, we use the World Bank (2016) classification that divides countries into four groups according to gross national income per capita. In line with the anecdotal evidence discussed above, high and low income countries appear to be the least affected.Footnote 9 The worst situation is in middle income countries, many of which recognize the role of research for development, and therefore strive to upgrade, but lag significantly behind advanced countries not only in technology, but in their ability to effectively evaluate and govern their emerging research systems. Yet the largest difference in the proclivity to predatory publishing is between lower middle income countries, such as Indonesia, India and the Philippines, and low income countries. Overall, therefore, there seems to be a non-linear, specifically inverse U-shaped, relationship.

Finally, as already menioned above, the low tendency towards predatory publishing in low income (the least developed) countries may be related to the small size of their public research sectors. To examine whether size matters, we divide the sample into quartiles according to the total number of articles published. Countries with small research sectors do not fall into the most frequent contributors to predatory journals, with the single exception of Tajikistan. In fact, the vast majority rank well below the world average. More than half of low income countries indeed fall into the small size category, and thus it is not surprising that the propensity to predatory publishing proves to be similarly low in both country groups. Again, there seems to be an inverse U-shaped relationship, albeit with a different shape of the distribution.

Next, results are reported by the source list we used to identify predatory journals using three categories: (i) Beall’s list of standalone journals; (ii) Beall’s list of publishers excluding Frontiers; and (iii) Frontiers. The latter is analyzed separately to account for the controversy surrounding the inclusion of Frontiers Research Foundation on Beall’s list of publishers, as already discussed above. Frontiers does exhibit a noticeably different pattern from the other two sources. Authors publishing in Frontiers journals are distributed far more evenly across the country groups and in some respects, such as along income per capita, display even an opposite tendency compared to the other sources lists. On the top 20 list of countries with the highest propensities to publish in Frontiers journals feature Austria, Switzerland, Netherlands, Belgium, Germany or Israel, and in these as well as most other advanced countries Frontiers is the dominant source.Footnote 10 As a result, the main patterns identified above are even more pronounced in the total figures excluding Frontiers. From this perspective, Frontiers truly does not look as a typical predatory publisher.

The absolute numbers of articles in predatory journals are also worthy of consideration. In countries with large research systems, predatory publishing can be quite extensive, even if the proportion to total articles does not seem problematic. The main case in point is China, which does not stand out in relative terms with 3.66% of predatory journal articles in the total national article count, but around 44 thousand articles published in predatory journals had at least one co-author from China; this is by far the largest number worldwide. This means that nearly every fourth predatory journal article has a Chinese co-author. Next are India and the United States, with almost every sixth and ninth predatory journal article co-authored by a researcher from that country, respectively. In these countries, there are legions of researchers who are willing to pay to have their work published in predatory journals.

Table 4 provides details on the top 20 most affected countries and the averages across all countries by field of research. The latter indicate that the worldwide propensity to publish in predatory journals is almost two times higher in Social and Life Sciences than in Health and Physical Sciences. Social Sciences are particularly ravaged by this problem in a number of countries: in 7 countries, including the relatively large research systems of Malaysia, Indonesia and Ukraine, more than one fifth of articles appear in predatory journals, and in 14 countries more than one tenth of articles fall into this category. Arguably, the credibility of the whole field is at stake here.

Indonesia, Iraq and Oman feature on the top 20 lists in all four fields and Egypt, Iran, Kazakhstan, Libya, Malaysia, Nigeria, Palestine, Sudan and Yemen in three. In these countries, predatory publication practices have apparently become a systemic problem at the national level, not limited to particular clusters. On the contrary, and perhaps even more interestingly at this point, there are countries in which only specific fields went rogue. For example, China is by far the worst in Health Sciences, but does not appear on any other field list.Footnote 11 Albania stands out in Social Sciences only. Likewise, India only looks disreputable in Life and Physical Sciences, Russia in Life and Social Sciences, and Ukraine in Social Sciences.Footnote 12

Overall, we have identified a handful of factors which seem to be relevant for explaining cross-country differences in the propensity to predatory publishing, and which beg for more elaborate examination. Nevertheless, tabulations of the data can only get us so far in isolating their individual effects. Due to limited space and because a combination of several factors appears to be in play, we do not delve deeper into descriptive evidence by field of research, but rather explore these patterns using a multivariate regression framework in the next section. The full results at the country-level in total and by field of science are available for download as supplementary information for this paper.Footnote 13

Regression analysis

In this section, we explore the cross-country differences with the help of an econometric model. The main focus of the analysis is on testing the hypothesized relationships between the level of economic development measured by GDP per capita, size of the (public) research sector measured by the total number of articles and the propensity to predatory publishing, while controlling for other relevant factors. The empirical model to be estimated is as follows:

where the outcome variable Y is the proportion of articles published in predatory journals, variously defined, GDP per capita represents the level of economic development, SIZE represents the size of the research sector, X is the set of country-level control variables, δ is a fixed effect for the field of research represented by respective dummies, i denotes a country, j denotes a field of research and ε is the standard error term. Hence, the basic unit of analysis is a field of research in a given country. Since differences between fields of research are fully accounted for by the fixed effects, the estimated coefficients of the country-level variables explain exclusively within fields variability.

The dependent variable is a proportion that falls between zero and one. The Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) estimator tends to produce predicted values outside of this range and assumes linear relationships. Both problems are addressed by using a fractional logit (binomial) in the Generalized Linear Models (GLM) framework. Robust standard errors derived from Huber-White sandwich estimators are reported. Only observations with at least 30 total articles in the respective country-field and with full data available for the explanatory variables are included in the estimation sample. As the result, the econometric analysis is limited to 630 observations in 163 countries.Footnote 14 All estimates are performed in Stata/MP 15.1.

Whenever possible we use continuous variables to measure the explanatory factors, as though the number of observations is essentially quadrupled by using the field specific data, the sample is still relatively small. As envisaged above, GDP per capita (PPP, constant 2011 international dollars) is used to measure the level of economic development and the total number of articles indexed in Scopus is used as a rough proxy for the size of the research sector. Oil and natural gas rents (% of GDP) are used to control for the availability of extra fiscal resources. Latitude and longitude of the country’s centroid, instead of plain continental dummies, are used to account for geography. However, the only way to control for the language zones is to use dummies. GDP per capita and the size of research sector variables are used in logs to curtail the impact of outliers. All variables refer to (if applicable averages over) the reference period 2015–2017. For descriptive statistics, definitions and sources of the variables entering the regression analysis, see "Appendix" Tables 6 and 7.

The regression analysis is used as a descriptive tool in this paper. The purpose of the regression model is to test whether the broad cross-country patterns identified above hold in a multivariate framework, when the possible influence of other relevant factors is accounted for. It should be emphasized that the cross-sectional nature of the data does not allow for testing of causality, the estimated relationships indicate correlations, and the results should therefore be interpreted with caution.

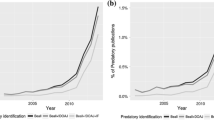

Table 5 provides results for the benchmark outcome variable of total predatory publishing (Column 1), then results are replicated separately by the source list (Columns 2–4) and finally estimated for the total, excluding Frontiers (Column 5). Since the descriptive overview revealed that there could be a non-linear relationship between the propensity to predatory publishing on the one hand and the level of economic development as well as the size of the research sector on the other hand, we test for this possibility by including the respective variables in squared terms.

GDP per capita has a significantly positive main effect, but the negative squared term indicates that there is indeed an inverse U-shaped relationship. The results confirm that the proclivity to predatory publishing has a tendency to increase with the level of economic development, but only up to a point, after which the relationship turns negative. Hence, countries at a medium level of development are the most vulnerable. Likewise, the size of the research sector comes out with a significantly positive main effect and a negative squared term, thus the same interpretation applies, albeit the relationship is estimated to be far less curvilinear.Footnote 15

Some of the control variables prove to have even more statistically significant coefficients. First, more reliance on oil and natural gas rents is strongly positively associated with predatory publishing. Hence, predatory publishing tends to occur when fortunes are perhaps hastily poured into supporting research. Of course, this is not to say that such resources should not be used to fund research, but there is a catch. Second, Arabic countries are confirmed to be particularly susceptible to predatory publishing, even after oil and natural gas rents and other factors are accounted for, so there is something special about this area. Further, English is assumed to primarily control for the suspected language bias of Beall’s lists and Scopus, but this worry is not supported by the results. Finally, longitude has a significantly positive coefficient, so farther east of the Greenwich meridian implies higher inclinations towards predatory publication.

As far as the comparison by source list is concerned, the results confirm that Frontiers has a different modus operandi than the rest of the pack. If only articles in Frontiers journals are considered, for instance, GDP per capita has statistically significant but opposite signs from the benchmark results. In fact, the model explains this outcome variable quite poorly, from which follows that a different approach is needed to get to bottom of what is up with this publisher. Although there is no evidence in the data presented upon which we can judge whether the inclusion of Frontiers on Beall’s list was justified or not, the results at the very least clearly indicate that Frontiers is atypical. Henceforth, therefore, we focus on the outcomes excluding Frontiers.Footnote 16

Figure 2 gives graphical representations of the estimated relationships of main interest, which provide a handy platform for discussing the results in more detail. The figures clearly illustrate that these relationships follow an inverse U-shaped curve. The propensity to predatory publishing increases with GDP per capita up to approximately the level of countries like India, Nigeria and Pakistanafter which, however, there is a steep decline. Along the size measure there is initially a steady increase of predatory publishing until a turning point at the level of countries with relatively large research systems like Malaysia and Saudi Arabia, which is followed by only a slight decrease for the largest ones. The overlapping confidence intervals indicate that, for GDP per capita, the relationship differs most significantly between medium and highly developed countries, while for the size measure the difference is mainly between small and medium research sectors. So what does this mean?

Estimated effects of GDP per capita (upper figure) and size of the research sector (lower figure) on the propensity to predatory publishing (total excluding Frontiers), GLM with logit link for binomial family, 2015–2017. Based on results in Column 5 of Table 5. Predictive margins with 90% confidence intervals are displayed

GDP per capita is used for a lack of better measurements that are more intimately related to how a research system is organized and that would be available for a broad sample of countries, including many developing ones. Nevertheless, GDP per capita tends to be highly correlated to many other salient measures. What is likely to make the key difference between medium and high developed countries that drives the results presented in this study is capability to perform meaningful research evaluation, including advanced scientometrics and peer-review of actual content of published papers, that does not fall back on only counting the number of articles indexed in Scopus or elsewhere, regardless of quality and merit. If the government is not able to set the right mix of incentives to the public research sector, which is arguably very difficult even in advanced countries, those who do not shy away from predatory publishing have free rein.

Size is an important consideration, as noted above, because large research systems are more complex and therefore notoriously more difficult for governments to evaluate, manage and steer than small systems. If two countries maintain equally primitive research evaluation frameworks, one with a large research sector composed of dozens of diverse institutions will tend to be more susceptible to predatory publishing than one with a tiny research sector composed of perhaps only a few easy-to-oversee workplaces. Large research systems suffer from a certain degree of anonymity, blind spots and dark corners, in which predatory publishing flourish. Around the turning point, however, the system becomes large enough to warrant investment in advanced research evaluation capabilities, which make life more difficult for those exploiting the loopholes, so that the relationship between predatory publishing and size flattens and even curves slightly down.

Conclusions

Taken at face value, the evidence presented in this paper indicates that countries at a medium level of economic development and with large research sectors are most susceptible to predatory publishing. This should be a dire warning for developing countries which devote large resources to support research, but which may not pay sufficient attention to upgrading their research governance capabilities, including research evaluation framework. Moreover, the evidence suggests that oil-rich and/or Arabic and/or eastern countries tend to be particularly vulnerable, which completes the picture of who should be primarily on the lookout for predators.

Nevertheless, the general patterns are from a bird's-eye view, so there are exceptions driven by idiosyncratic factors. The prime example of an outlier appears to be Albania, which does not feature most of the high-risk characteristics, but still is among the most affected countries. Predatory publishing is a truly global phenomenon, from which no emerging research system is entirely safe. Policymakers in developing countries that do not fit the description of the main risk group should not be fooled into thinking that the problem does not concern them, because if they flinch in their vigilance, their homeland may end up on the list of the most affected countries next time.

The results are broadly in line with previous estimates by Shen and Björk (2015), Xia et al. (2015), Demir (2018), as well as Wallace et al. (2018), in the sense that Asia and North Africa provide the most fertile grounds for predatory publishing and that in particular India and Nigeria belong to the main sources. However, this paper not only gathered one of the most comprehensive databases of predatory journals, and used far more complete evidence than previous studies, but also provided a much higher level of granularity on the cross-country differences. In fact, a number of countries not mentioned in previous studies are shown here to suffer greatly from the problem of predatory publishing. In addition, this paper is the first to study the cross-country differences systematically in an econometric framework.

A major limitation of this study is that we can only speculate that the way in which research is evaluated in each country makes the primary difference, whether this includes research organizations at the national level, project proposals by funding agencies, and/or even individuals working on career progression. Ideally, we would like to take characteristics of the research evaluation framework directly into account, including whether evaluation primarily concerns quantity or quality, whether formulae based on quantitative metrics is used, how advanced the underlying bibliometric approach is, whether insights from peer review assessment are factored in, and, consequently, what principles are applied when allocating research funding. Unfortunately, indicators of this kind are not available for more than a handful of advanced countries, which are not the most relevant here. To pin down the impact of these factors on the propensity to predatory publishing remains an important challenge for future research on this topic.

Another limitation is the cross-sectional nature of the analysis that, as explained above, stems from the fact that historical data is not reliable. Longitudinal data would allow for more elaborate tests, particularly with respect to causality, than those employed in this paper. There are also likely to be lags in the cause–effect relationships that could be detected when long time series become available. In any case, the three-year period studied here is rather short, as predatory publishing is a relatively recent and fairly dynamic phenomenon. This may have influenced the results and the list of most affected countries may look somewhat different if a similar exercise is repeated in a few years, which would be desirable.

It should be stressed that the results of this paper should not be interpreted to mean that developing countries should invest less in research, because this would undermine their emerging and often fragile national innovation systems and ultimately thwart productivity growth (Fagerberg and Srholec 2009). However, it is fair to issue a cautionary note that predatory publishing has the potential to complicate research evaluation and therefore effective allocation of research funding greatly in many corners of the world. Developing countries aiming to embark on a technological catch-up trajectory need to take these intricacies more seriously than ever.

Last, but not least, there is the underlying question why there are predatory journals in Scopus in the first place. Journals indexed in Scopus should fulfil minimum quality requirements (Scopus 2019). However, these criteria are either rather formal, derived from bibliometrics or rely on what the journal declares about itself. Predatory journals manage to look like regular scientific outlets on the outside, their bibliometric profile might not differ that much from other fringe journals and they do not shy away from lying about their editorial practices. So this filter is not likely to be effective in keeping out fake journals that are good pretenders. Scopus needs to find a way to fact-check whether the journal adheres to the declared editorial practices, including most prominently how the peer-review process is performed in practice. Unless the selection criteria are upgraded and/or the bar for inclusion is raised significantly, fake scientific journals will keep creeping in the database. In the meantime, evaluators, research managers or university rankings that use Scopus data as inputs in their decisions need to be mindful about it.

Change history

06 September 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-04149-w

Notes

Anonymous authors continue with Beall’s work and regularly update his list on this website: https://beallslist.weebly.com.

The Ulrichsweb search engine uses a ‘fuzzy’ search which does not require perfect matching of strings. For example, when we searched for Academe Research Journals, journals of Academic Research Journals were also found. This is beneficial because the search is robust to typos, interpunction signs, and small errors written in the search terms. However, it also requires careful manual verification of search results.

Unfortunately, the Scopus database does not directly provide harmonized data on the number of authors by country that published in a journal. However, we can count the number of countries, to which at least one author of an article is affiliated, by journal. Based on data for 324 predatory journals and 23,387 other Scopus journals, the average number of country-affiliations turns out to be 1.20 and 1.23, respectively, hence there is not a significant difference and the bias is likely to be rather small. We thank one of the anonymous reviewers for pointing out this potential shortcoming.

Only 1,069 predatory journal articles had an ‘undefined’ country of origin. Hence, the overwhelming majority of the articles found are included in our analysis.

More detailed stratification, such as dividing Asia into South, East, Central and West, or Africa into North and Sub-Saharan, is not advisable, because there are few countries in some subgroups, which would make averages unreliable.

For example, there are four countries in which both English and French are spoken by at least 20% of the population (Canada, Cameroon, Israel and Lebanon). Nevertheless, the vast majority of countries are assigned to a single language zone.

The high income group includes Persian Gulf countries, namely Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates, which are rich primarily thanks to oil drilling in the region and in which, except only of Qatar, the propensity to predatory publishing is significantly above the world average. If these countries are excluded, the average propensity to predatory publishing in the high income group drops further down to 1.74%.

Approximately two-thirds of predatory journal articles from advanced countries are published by Frontiers. South Korea is a major outlier among advanced countries, not only because of its high overall penetration of predatory publishing, but also in the fact that the vast majority of these articles are not in Frontiers journals. Taiwan and Slovakia are similar but to a lesser degree.

Nevertheless, one must not forget the caveat repeatedly mentioned above that the data predominantly includes journals published in English. China not only has a different language but also its own writing system; thus local problems with the predatory model of publication may largely escape our attention.

In general, there are far more former socialist countries, especially former members of the Soviet Union, on the top 20 list in Social Sciences than in other fields. Social Sciences were particularly isolated, indoctrinated and devastated during the communist era, so it is not surprising that this is the case.

Note that most of the patterns by country groups identified in the total data also apply by field of research, as also vindicated by the regression results below.

Cuba, Eritrea, North Korea, Somalia and Syria are excluded due to missing data on GDP per capita. Comoros, Djibouti, Timor-Leste and Turkmenistan are eliminated because they did not generate more than 30 total articles in any of the fields of research.

If the squared terms are excluded from the model, both coefficients come out highly statistically significant, but GDP per capita has a negative sign while the size of research sector has a positive sign.

It needs to be emphasized that the authors of this article have never had any connection to the Frontiers Research Foundation or any of their journals in any capacity.

References

Baguess, M., Sylos-Labini, M., & Zinovyeva, N. (2019). A Walk on the Wild Side: `Predatory’ journals and information asymmetries in scientific evaluations. Research Policy, 48(2), 462–477.

Beall, J. (2013). Predatory publishing is just one of the consequences of gold open access. Learned Publishing., 26(2), 79–84.

Beall, J. (2015). Criteria for Determining Predatory Open-Access Publishers. Retrieved May 19, 2018, from https://beallslist.weebly.com/uploads/3/0/9/5/30958339/criteria-2015.pdf.

Beall, J. (2016). Scholarly Open Access: Critical analysis of scholarly open-access publishing (Beall’s blog). Retrieved April 1, 2016, from https://scholarlyoa.com; shutdown January 2018, archived at https://archive.org/web/.

Berger, M., & Cirasella, J. (2015). Beyond Beall’s list better understanding predatory publishers. College and Research Libraries News, 76, 132–135.

Bloudoff-Indelicato, M. (2015). Backlash after Frontiers journals added to list of questionable publishers. Nature, 526, 613.

Bohannon, J. (2013). Who’s afraid of peer-review. Science. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.342.6154.60.

Butler, D. (2013). The dark side of publishing. Nature, 495(7442), 433.

Cobey, K. D., Lalu, M. M., Skidmore, B., Ahmadzai, N., Grudniewicz, A., & Moher, D. (2018). What is a predatory journal? A scoping review. F1000Research, 7, 1001.

Crawford, W. (2014a). Ethics and access 1: The sad case of Jeffrey Beall. Cites and Insights, 14(4), 1–14.

Crawford, W. (2014b). Journals, journals and wannabes: Investigating the list. Cites and Insights, 14(7), 1–24.

Cyranoski, D. (2018) China awaits controversial blacklist of ‘poor quality’ journals. Nature News. Retrieved May 19, 2018, from https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-07025-5.

Demir, S. B. (2018). Predatory journals: Who publishes in them and why? Journal of Informetrics, 12(4), 1296–1311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2018.10.008.

Demir, S. B. (2020). Scholarly databases under scrutiny. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 52(1), 150–160.

Eriksson, S., & Helgesson, G. (2017a). The false academy: Predatory publishing in science and bioethics. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 20(2), 163–170.

Eriksson, S., & Helgesson, G. (2017b). Time to stop talking about “predatory journals.” Learned Publishing, 31(2), 181–183. https://doi.org/10.1002/leap.1135.

Fagerberg, J., & Srholec, M. (2009). Innovation systems, technology and development: Unpacking the relationship(s). In B.-A. Lundvall, K. J. Joseph, C. Chaminade, & J. Vang (Eds.), Handbook of innovation systems and developing countries (pp. 83–115). Cheltenham, Edward Elgar: Building domestic capabilities in a global context.

Gallup, J. L., Sachs, J. D., & Mellinger, A. D. (1999). Geography and economic development. International Regional Science Review, 22(2), 179–232.

Good, B., Vermeulen, N., Tiefenthaler, B., & Arnold, E. (2015). Counting quality? The Czech performance-based research funding system. Research Evaluation, 24, 91–105.

Kurt, S. (2018). Why do authors publish in predatory journals? Learned Publishing, 31(2), 141–147.

Mayer, T. Zignago, S. (2011). Notes on CEPII’s distances measures: The GeoDist database. CEP II, Working Paper No 2011–25. http://www.cepii.fr/CEPII/en/publications/wp/abstract.asp?NoDoc=3877.

Mongeon, P., & Paul-Hus, A. (2016). The journal coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: A comparative analysis. Scientometrics, 106(1), 213–228.

Perlin, M. S., Imasato, T., & Borenstein, D. (2018). Is predatory publishing a real threat? Evidence from a large database study. Scientometrics, 116(1), 255–273.

Scopus. (2018a). Scopus on-line database.https://www.scopus.com.

Scopus. (2018b). Scopus Source List (May 2018 version). Current version is Retrieved May 21, 2019, from https://www.scopus.com/sources.

Scopus. (2019). Content policy and selection. Retrieved May 19, 2019, from https://www.elsevier.com/solutions/scopus/content/content-policy-and-selection.

Shamseer, L., Moher, D., Maduekwe, O., Turner, L., Barbour, V., Burch, R., et al. (2017). Potential predatory and legitimate biomedical journals: Can you tell the difference? a cross-sectional comparison. BMC Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-017-0785-9.

Shen, C., & Björk, B.-C. (2015). Predatory’ open access: a longitudinal study of article volumes and market characteristics. BMC Medicine., 13(230), 1–15.

Silver, A. (2017). Pay-to-view blacklist of predatory journals set to launch. Nature News. Retrieved May 19, 2019, from https://www.nature.com/news/pay-to-view-blacklist-of-predatory-journals-set-to-launch-1.22090.

Somoza-Fernández, M., Rodríguez-Gairín, J. M., & Urbano, C. (2016). Presence of alleged predatory journals in bibliographic databases: Analysis of Beall’s list. El Profesional de la Información, 25(5), 730.

Straumsheim, C. (2017). No More 'Beall's List'. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved March 27, 2017, from https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2017/01/18/librarians-list-predatory-journals-reportedly-removed-due-threats-and-politics.

Ulrichsweb. (2016). Ulrichsweb–Global Serials Directory. 2019. Retrieved April 1, 2016, from http://ulrichsweb.serialssolutions.com/.

Wallace, F. H., & Perri, T. J. (2018). Economists behaving badly: Publications in predatory journals. Scientometrics, 115, 749–766.

World Bank. (2016). How does the World Bank classify countries? Retrieved October 10, 2016, from https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/378834-how-does-the-world-bank-classify-countries.

World Bank. (2018). World development indicators (last updated July 2018). New York: World Bank.

Xia, J., Harmon, J. L., Connolly, K. G., Donelly, R. M., Anderson, M. R., & Howard, H. A. (2015). Who Publishes in Predatory Journals? Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 66(7), 1406–1417.

Acknowledgements

Financial support from the Czech Academy of Sciences for the R&D&I Analytical Centre (RaDIAC) and from the Czech Science Foundation (GAČR) project 17-09265S is gratefully acknowledged. Earlier versions of the paper were presented at the IDEA think-tank seminar Predatory Journals in Scopus, Prague, November 16, 2016, the Scopus Content Selection and Advisory Board Meeting, Prague, November 3, 2017 and the 17th International Conference on Scientometrics and Infometrics, Rome, September 2 – 9, 2019. We thank the participants at these events for their useful comments and suggestions. Martin Srholec also thanks his beloved wife Joanna for her support of the preparation of a revised version of the manuscript during the heat of the COVID-19 crisis. All the usual caveats apply.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article has been retracted. Please see the retraction notice for more detail:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-04149-w

Supplementary information

About this article

Cite this article

Macháček, V., Srholec, M. RETRACTED ARTICLE: Predatory publishing in Scopus: evidence on cross-country differences. Scientometrics 126, 1897–1921 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03852-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03852-4