Story highlights

Report says former PM Cameron failed to develop sound strategy

Intervention contributed to a political chaos, inquiry found

Britain’s military intervention in Libya was based on “inaccurate intelligence” and “erroneous assumptions,” a report released Wednesday found, pointing the finger at former Prime Minister David Cameron for failing to develop a sound Libya strategy.

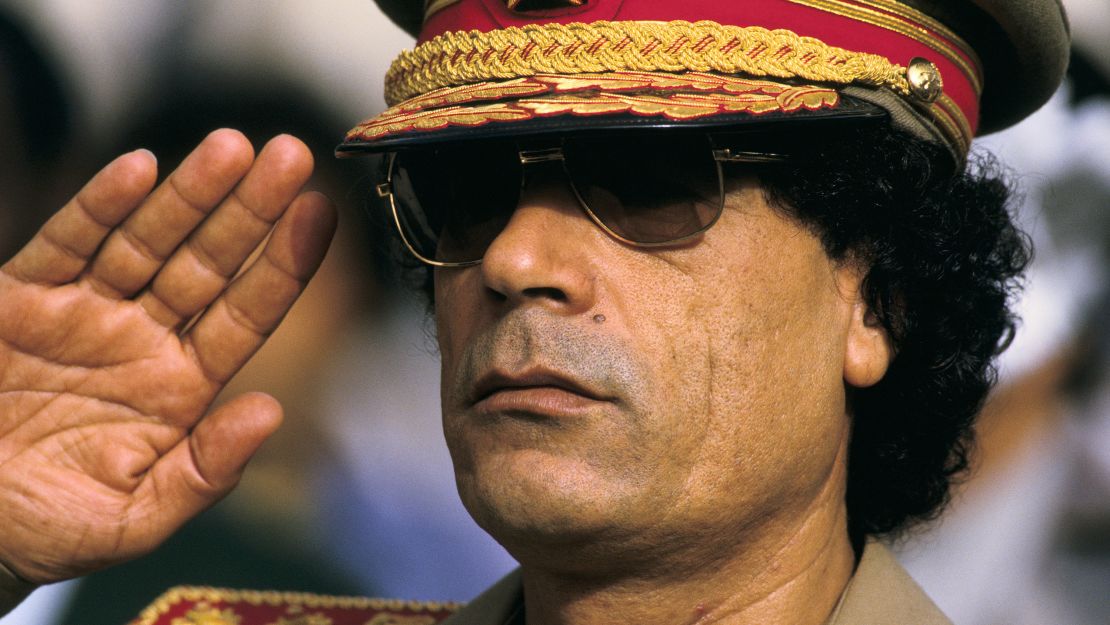

The United Kingdom and France led the international intervention in Libya in 2011 with the aim of protecting civilians from forces loyal to then-leader Moammar Gadhafi.

But Britain’s Foreign Affairs Committee found that the Cameron-led government “failed to identify that the threat to civilians was overstated and that the rebels included a significant Islamist element.”

Policy ‘drifted towards regime change’

“The consequence was political and economic collapse, inter-militia and inter-tribal (warfare), humanitarian and migrant crises, widespread human rights violations and the growth of ISIL in North Africa,” the report said, using an alternative name for the ISIS militant group, which has gained control of parts of Libya.

The committee found that Britain’s policies on Libya that had intended to protect civilians had instead “drifted towards regime change and was not underpinned by strategy to support and shape post-Gadhafi Libya.”

“This report determines that UK policy in Libya before and since the intervention of March 2011 was founded on erroneous assumptions and an incomplete understanding of the country and the situation,” said the chairman of the Foreign Affairs Committee, MP Crispin Blunt, in a statement.

“The UK’s actions in Libya were part of an ill-conceived intervention, the results of which are still playing out today.”

He said “other political options were available” and might have come at a lower cost to both Libya and the United Kingdom. He added that there was a “lack of understanding of the institutional capacity of the country” that “stymied Libya’s progress in establishing security on the ground.”

The committee said it had spoken to all key figures in the decision to intervene in Libya except for Cameron, who declined to take part in the inquiry, citing “the pressures on his diary,” adding that other members of government had provided the information needed, the report said.

World ‘turned its back on Libya’

The report said Cameron “was ultimately responsible for the failure to develop a coherent Libya strategy,” despite establishing a National Security Council.

It pointed out that when Cameron sought and received parliamentary approval for the intervention, he assured it was not aimed at regime change.

“In April 2011, however, he signed a joint letter with United States President Barack Obama and French President Nicolas Sarkozy setting out their collective pursuit of ‘a future without (Gadhafi),’” the report said,

But a spokesperson for Britain’s Foreign and Commonwealth Office told CNN that the decision to intervene in Libya “was an international one, called for by the Arab League and authorized by the United Nations Security Council.”

The FCO spokesperson said Gadhafi “was unpredictable, and he had the means and motivation to carry out his threats. His actions could not be ignored, and required decisive and collective international action … we stayed within the United Nations mandate to protect civilians.”

The inquiry, which took evidence from key figures – including former Prime Minister Tony Blair, military chiefs and academics – said the United Kingdom’s policy decision followed those made in France, which “led the international community in advancing the case for military intervention in Libya,” in which the United States became involved and played a key role.

The international intervention, which followed an attempted uprising during the Arab Spring, paved the way for the removal of Gadhafi, who was eventually killed by the side of a road by supporters of the de facto government.

But his death gave way to chaos, including inter-ethnic and tribal rivalries, that saw the country break down into city states, many of those with competing militias, CNN International Diplomatic Editor Nic Robertson said.

“But the most damning indictment that Libyans level against the international community is that it turned its back on Libya after Gadhafi was killed,” he said.

An invitation to ISIS

The political upheaval created a vacuum for militant groups such as ISIS, which has taken advantage of the country’s weakened institutions to spread its influence and strongholds beyond Syria and Iraq.

ISIS militants are clinging on in the coastal city of Sirte and scattering to its south as they are attacked on the ground by militia that support the nascent Libyan government and from the air by US airstrikes.

Libya’s current internationally recognized government has struggled to quell the chaos and keep its grip on power. In 2014, Islamist militias forced the internationally recognized government to flee the capital Tripoli. They took refuge in the east of the country.

The country has also become a gateway to Europe for migrants, many from sub-Sahara Africa, who have used the country to escape over the mostly open borders and reach the Mediterranean.

Oil production in resource-dependent Libya has dived since the intervention, the economy suffering a double blow as world oil prices plunge.

The World Bank has reported that Libya generated $41.14 billion GDP in 2014, the latest year for which figures are available, and that the average Libyan’s annual income decreased from $12,250 in 2010 to $7,820.

Libya is likely to experience a budget deficit of some 60% of GDP in 2016, the report said.

The FCO spokesperson said “four decades of [Gadhafi] misrule” had inevitably left Libya facing “huge challenges,” but that the UK was working to support the internationally-recognized Government of National Accord.

“We have allocated £10 million ($13.2 million) this year to help the new government to restore stability, rebuild the economy, defeat Daesh [ISIS] and tackle the criminal gangs that threaten the security of Libyans and exploit illegal migrants.”