Al-Dawayima, Dawaymeh or Dawayma (Arabic: الدوايمة) was a Palestinian town, located in the former Hebron Subdistrict of Mandatory Palestine, and in what is now the Lakhish region, some 15 kilometres south-east of Kiryat Gat.[5]

al-Dawayima

الدوايمة ad-Dawayima | |

|---|---|

| Etymology: The little Dom tree[1] | |

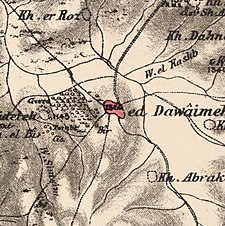

A series of historical maps of the area around Al-Dawayima (click the buttons) | |

Location within Mandatory Palestine | |

| Coordinates: 31°32′10″N 34°54′43″E / 31.53611°N 34.91194°E | |

| Palestine grid | 141/104 |

| Geopolitical entity | Mandatory Palestine |

| Subdistrict | Hebron |

| Date of depopulation | 29 October 1948[4] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 60,585 dunams (60.585 km2 or 23.392 sq mi) |

| Population (1945) | |

| • Total | 3,710[2][3] |

| Cause(s) of depopulation | Military assault by Yishuv forces |

| Current localities | Karmei Katif; Amatzia |

According to a 1945 census, the town's population was 3,710, and the village lands comprised a total land area of 60,585 dunums of which nearly half was cultivable. The population figures for this town also included the populations of nearby khirbets, or ancient villages. During the 1948 Palestine war, the al-Dawayima massacre occurred. According to Saleh Abd al-Jawad an estimated 80-200 civilian men, women and children were killed.[6] According to John Bagot Glubb, a UN report said that 30 women and children were killed.[7]

In 1955, the ruins of the town were replaced by the Israeli moshav of Amatzia.

History edit

It has been occasionally identified with the Old Testament town of Bosqat, the home of Josiah's mother Jedidah (2 Kings, 22:1) though the association has not found widespread acceptance.[8]

Al-Dawayima's historical remains encompass a long period from the Bronze Age, through to the Persian and Hellenistic, down to the Ottoman period. Bulldozing what remains of the Palestinian village to prepare a new Israeli village has revealed an ancient olive press, a columbarium cave, a villa from the Second Temple era, and both mikvehs and cisterns.[5]

The "core clan" of Al-Dawayima were the Ahdibs, who traced their origin to the Muslim conquest and settlement of Palestine in the seventh century.[9]

Ottoman era edit

In the late Ottoman era, in May, 1838, Edward Robinson visited during harvesting time. He noted that Al-Dawayima was situated on a hill, with a view of several villages to the east. During the harvest, several Christians from Beit Jala were employed here as labourers; the barley harvest was coming to an end, while the wheat harvest was just beginning.[10] He further noted it as a Muslim village, between the mountains and Gaza, but subject to the government of el-Khulil.[11]

In 1863 Victor Guérin visited twice, and he estimated that the village contained 900 inhabitants,[12] while an Ottoman village list from about 1870 found that Dawaime had only a population of 85, in a total of 34 houses, though the population count included men, only. It also noted that it was located west of Hebron.[13][14]

In 1883, the PEF's Survey of Western Palestine described al-Dawayima as a village on a high stony ridge that had olive groves beneath it. On a higher ridge to the west stood a shrine that was topped by a white stone.[15]

-

Map with Al-Dawayima dated 1894. bottom centre

-

Al-Dawayima 1933 1:20,000

-

Al-Dawayima 1945 1:250,000

The people of al-Dawayima were Muslims. They maintained several religious shrines, chief among them the shrine of Shaykh ´Ali. This shrine had a large courtyard, a number of rooms, and one large hall for prayers, and was surrounded by fig and carob trees and cactuses. It attracted visitors from the neighboring villages.[16] A mosque was located in the village center, it was maintained by the followers of al-tariqa al-khalwatiyya, a Sufi mystic order founded by Shaykh Umar al-Khalwati (d.1397)[17]

British Mandate era edit

In the 1922 census of Palestine conducted by the British Mandate authorities, AI Dawaima had a population of 2,441 inhabitants, all Muslims,[18] increasing in the 1931 census to 2,688, still all Muslim, in a total of 559 houses.[19]

The villagers expanded and renovated the village mosque in the 1930s, and added a tall minaret.[16]

In the 1945 statistics, Al-Dawayima had a population of 3,710 Muslims,[2] with a total land area of 60.585 dunums of land.[3] By 1944/45, 21,191 dunums of village land were allotted to cereals, 1,206 dunums were irrigated or used for orchards,[20] while 179 dunams were built-up (urban) areas.[21]

The Institute for Palestine Studies and The Palestinian Museum note the following about the town's built environment:

"Shops were scattered throughout the various neighborhoods of the village center. Houses were made of stone and mud, separated by narrow streets and alleys. The older houses were clustered closely together. Each set of houses shared a hawsh, a large courtyard that provided space for women to do their domestic chores, for children to play, and for families to gather in the evening and on special occasions. As the village expanded people began to build new houses outside of the village core. These new houses were larger and built of whitewashed stone some of them had thick, stone walls and were called jidaris (from the Arabic word for wall, jidar)....Each house had two levels: the upper level was occupied by the family members and the lower level by their animals. The houses of the well-to-do villagers had their own courtyards and large guest rooms, in addition to animal stables."[22]

1948 war and aftermath edit

Al-Dawaymima was captured by Israel's Eighty Ninth Battalion (commanded by Dov Chesis) of the 8th Armored Brigade led by the founder of the Palmach, Yitzhak Sadeh, after Operation Yoav on 29 October 1948, five days after the start of the truce. It was the site of the al-Dawayima massacre in which 80–200 civilians were killed, including women and children.[6] According to Lieutenant-General John Bagot Glubb, a British officer stationed with Jordanian's Arab Legion in Bethlehem and Hebron at that time, the massacre was calculated to drive out the villagers and had been reported by UN observers to involve 30 deaths.[23] The massacre was cited by Yigal Allon as the reason for the halting of the creeping annexation that included Bayt Jibrin, Qubeiba and Tel Maresha.[24] It was also seen as a reprisal by the Israelis for the massacre of Jews in Kfar Etzion months before, on May 13, 1948, by Palestinian fighters and some members of the Arab Legion.[25]

The moshav of Amatzia was established in 1955 on land that had belonged to Al-Dawayima.[26] According to the Palestinian historian Walid Khalidi :

"The site has been fenced in. A cowshed, a chicken coop, and granaries have been built at its center (which has been leveled). The southern side of the site contains stone terraces and the remnants of a house. The eastern side is occupied by the residential area of the moshav."

In 2013, the whole area, apart from some ancient Jewish remains, was bulldozed to pave the way for the erection of a new community called Karmei Katif, which was completed in 2016 and which houses evacuees of the Gaza Strip settlements. The new name is reminiscent of Gush Katif.[5]

Culture edit

A woman's thob (loose fitting robe with sleeves) dated to about 1910 that was produced in Al-Dawayima is part of the Museum of International Folk Art (MOIFA) collection at Santa Fe. The dress is of hand-woven blue indigo linen. The embroidery is in predominantly red silk cross-stitch, with touches of violet, orange, yellow, white, green and black. The upper half of the qabbeh (the square chest panel) is embroidered with alternating columns of diamonds, (a pattern known as el-ferraneh), and eight-pointed stars, (called qamr ("moons")). The lower half of the qabbeh is in the qelayed ("necklaces") pattern. The side-panels of the skirt are completely covered with embroidered columns. Among the patterns used here are: nakhleh ("palm") motif, ward-wil-aleq ("rose-and-leech") and khem-el-basha ("the pashas tent"). Each column is topped with various trees. There is no embroidery on the long, pointed sleeves.[27]

The village is often featured in the works of Palestinian artist Abdul Hay Mosallam who was expelled from it in 1948.

By 2011, two books about the village history had been published.[28]

In popular culture edit

- In the 2008 film Salt of this Sea, Al-Dawayima is the village which Emad, the male protagonist, hails from. The village ruins serve as the temporary residence of the main characters, Emad and Soraya. The film is dedicated to the memory of the Al-Dawayima massacre.

Families edit

- Sanwar (سنور)

- Abd al-dean (عبد الدين)

- Abu Subaih (أبوصبيح)

- Abu-Farwa (ابوفروه)

- Abu-Galyeh (أبوغالية)

- Abu-Galyoun (أبو غليون)

- Abu-Halemah(أبوحليمة)

- Abu-Haltam (أبو حلتم)

- Abu-Kadra (أبو خضرة)

- Abu-Matr (أبو مطر)

- Abu-Me'alish (أبومعيلش)

- Abu-Rahma (ابورحمة)

- Abu-Rayan (أبو ريان)

- Abu-Safyeh (أبو صفية)

- Abu-Sugair (أبو صقير)

- Afaneh (عفانه)

- Al-Absi (العبسي)

- Al-Adarbeh (العداربة)

- Al-Aqtash (القطيشات)

- Al-Atrash (الأطرش)

- Al-Ayaseh (العيسه)

- Al-Hijouj (الحجوج)

- Al-Jamarah (الجمرة)

- Al-Jawawdeh (الجواودة)

- Al-Kateeb (الخطيب)

- Al-Khodour(الخضور)

- Al-Maqusi(المقوسي)

- Al-Mallad (الملاد)

- Al-Manasra (المناصرة)

- Al-Najaar (النجار)

- Al-Qaisieh (القيسيه)

- Al-Sabateen(السباتين)

- Al-Turk (الترك)

- Al-Zaatreh (الزعاترة)

- Asha (عشا)

- Basbous(بصبوص)

- Ead (عيد)

- El-Ghawanmeh (الغوانمه)

- Ganem (غانم)

- Hamdan (حمدان)

- Harb (حرب)

- Hudaib (هديب)

- Hunaif (حنيف)

- Ms'ed (مسعد)

- Nashwan (نشوان)

- Sa'adeh (سعادة)

- Shahin (شاهين)

- Sundoqa (صندوقه)

- Zebin (زبن)

Famous residents edit

See also edit

References edit

- ^ Palmer, 1881, p. 367

- ^ a b Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 23

- ^ a b c Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 50 Archived 2011-06-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. xix, village #324. Also gives cause for depopulation

- ^ a b c Zafrir Rinat, 'Bulldozing Palestinian History on Israel's southern hills,' at Haaretz 22 June 2013.

- ^ a b Saleh Abdel Jawad (2007), Zionist Massacres: the Creation of the Palestinian Refugee Problem in the 1948 War, in Benvenisti & al, 2007, pp. 59–127 See p. 67

- ^ Glubb, 1957, pp. 211-212

- ^ Jennifer L. Groves, 'Boskath', in David Noel Freedman, (ed.) Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible, Wm B.Eerdsmans/Amsterdam University Press 2000 p.198.

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 469

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 2, pp. 400-402

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, Appendix 2, p. 117

- ^ Guérin, 1869, pp. 342-3, 361

- ^ Socin, 1879, p. 151

- ^ Hartmann, 1883, p. 144 found 100 houses, way more than Socin

- ^ Conder and Kitchener, 1883, SWP III, p.258. Also quoted in Khalidi, 1992, p. 213.

- ^ a b Hudayb, 1985, p. 54. Cited in Khalidi, 1992, p. 213

- ^ Glassé, 1989, p. 221. Cited in Khalidi, 1992, p. 213

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table V, Sub-district of Hebron, p. 10

- ^ Mills, 1932, p. 28

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 93 Archived 2012-09-07 at archive.today

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 143 Archived 2013-01-31 at archive.today

- ^ "al-Dawayima — الدَوايمَة". Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question – palquest. Retrieved 2023-11-12.

- ^ Glubb, 1957, pp. 211-212. "The Israelis were now deliberately driving out all Arabs, a process assisted now and then but the usual 'calculated massacre'. On October 31st, United Nations observers reported that the Israelis had killed thirty women and children at Dawaima (Dawayima), west of Hebron. It would be an exaggeration to claim that great numbers were massacred. But just enough were killed, or roughly handled, to make sure that all the civilian population took flight, thereby leaving more and more land vacant for future Jewish settlement. These particular villages west of Hebron were to remain vacant and their lands uncultivated for eight years."

- ^ Shapira, 2008, p. 248

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 469 and Morris, 2008, p. 333.

- ^ Khalidi, 1992, p.215

- ^ Stillman, 1979, pp. 56-57

- ^ Davis, 2011, pp. 30 -31

Bibliography edit

- Aladjem, Emil; Gendler, Simeon (2012-11-07). "Amazya, Survey" (124). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Aladjem, Emil; Gendler, Simeon (2012-12-23). "Amazya, Al-Dawayima" (124). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Aladjem, Emil (2012-12-23). "Amazya South" (124). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Benvenisti, E., ed. (2007). Israel and the Palestinian Refugees. Berlin, Heidelberg, New-York: Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-68160-1.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1883). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 3. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Davis, Rochelle (2011). Palestinian Village Histories: Geographies of the Displaced. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-7313-3.

- Glassé, Cyril (1989): The Concise Encyclopedia of Islam. San Francisco: Harper & Row Cited in Khalidi.

- Glubb, J.B. (1957). A Soldier with the Arabs. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945.

- Guérin, V. (1869). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 1: Judee, pt. 2. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center. Archived from the original on 2018-12-08. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- Hartmann, M. (1883). "Die Ortschaftenliste des Liwa Jerusalem in dem türkischen Staatskalender für Syrien auf das Jahr 1288 der Flucht (1871)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 6: 102–149.

- Hudayb, Musa (1985): Qaryat al-Dawayima (The village of al-Dawayima). Amman: Dar al-jalil li al-nashr. Cited in Khalidi.

- Khalidi, W. (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Morris, B. (2008). 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-1-902210-67-4.

- Nahshoni, Pirhiya; Lender, Yeshayahu (2010-09-07). "Amazya Forest, Survey" (122). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 2. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Seriy, Gregory (2009-08-04). "Amazya East" (121). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Shapira, A. (2008). Yigal Allon; Native Son; A Biography. Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-4028-3.

- Socin, A. (1879). "Alphabetisches Verzeichniss von Ortschaften des Paschalik Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 2: 135–163.

- Stillman, Yedida Kalfon (1979). Palestinian Costume and Jewelry. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-8263-0490-7. (A catalog of the Museum of International Folk Art (MOIFA) at Santa Fe's collection of Palestinian clothing and jewelry.)

- Varga, Daniel; Israel, Yigal (2014-05-04). "Amazya" (126). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

External links edit

- Welcome to al-Dawayima

- al-Dawayima, Zochrot

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 20: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- al-Dawayima at Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center