Graffiti in New York City has had a substantial local, national, and international influence.

Growth of graffiti culture in New York edit

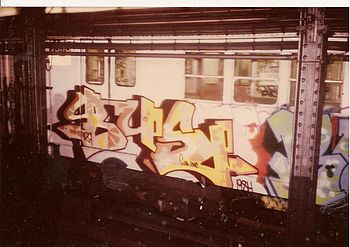

Graffiti began appearing around New York City with the words "Bird Lives"[1] but after that, it took about a decade and a half for graffiti to become noticeable in NYC. So, around 1970 or 1971, TAKI 183 and Tracy 168 started to gain notoriety for their frequent vandalism.[2] Using a naming convention in which they would add their street number to their nickname, they "bombed" a train with their work, letting the subway take it throughout the city.[2][3] Bubble lettering was popular among perpetrators from the Bronx, but was replaced with a new "wildstyle", a term coined by Tracy 168 and a legendary original Graffiti crew with over 500 members including Blade, Cope 2, T Kid 170, Cap, Juice 177, and Dan Plasma.[4][5] Graffiti tags started to grow in style and size.[3] Notable names from that time include DONDI, Lady Pink, Zephyr, Julio 204, Stay High 149, PHASE 2.[3][4]

Graffiti was growing competitive and artists desired to see their names across the city.[3] Around 1974 suspects like Tracy 168, CLIFF 159 and BLADE ONE started to create works with more than just their names: they added illustrations, full of scenery and cartoon characters, to their tags, laying the groundwork for the mural-car.[3] The standards from the early 1970s continue to evolve, and the late 1970s and early 1980s saw new styles and ideas. As graffiti spread beyond Washington Heights and the Bronx, a graffiti crime wave was born. Fab 5 Freddy (Friendly Freddie, Fred Brathwaite) was one of the most notorious graffiti figures of that era. He notes how differences in spray technique and letters between Upper Manhattan and Brooklyn began to merge in the late 1970s: "out of that came 'Wild Style'."[6] Fab 5 Freddy is often credited with helping to spread the influence of graffiti and rap music beyond its early foundations in the Bronx, and making links in the mostly white downtown art and music scenes. It was around this time that the established art world started becoming receptive to the graffiti culture for the first time since Hugo Martinez's Razor Gallery in the early 1970s.

The growth of graffiti in New York City was enabled by its subway system, whose accessibility and interconnectedness emboldened the movement, who now often operated through coordinated efforts.[3][7] It was further left unchecked due to the budgetary restraints on New York City, which limited its ability to remove graffiti and perform transit maintenance.[3] Mayor John Lindsay declared the first war on graffiti in 1972, but it would be a while before the city was able and willing to dedicate enough resources to that problem to start impacting the growing subculture.[2][3]

The Abraham Beame Administration established a police squad of about 10 police officers to work in anti graffiti capacity. The squad attended informal meetings and socialized with minor suspects to gather information to help them apprehend leaders. Although the squad gathered information on thousands of graffiti vandals, inadequate manpower prevented them from following through with arrests.[8]

Graffiti vandal arrests in New York City were reported at around 4,500 between 1972 and 1974, 998 in 1976, 578 in 1977, 272 in 1978, 205 in 1979.[8]

Decline of New York City graffiti subculture: enforcement and control edit

As graffiti became associated with crime, many demanded that the government take a more serious stance towards it, particularly after the popularization of broken windows theory.[2][9][10] By the 1980s, increased police surveillance and implementation of increased security measures (razor wire, guard dogs) combined with continuous efforts to clean it up led to the weakening of New York's graffiti subculture.[7] As a result of subways being harder to paint, more writers went into the streets, which is now, along with commuter trains and box cars, the most prevalent form of writing. But the streets became more dangerous due to the burgeoning crack epidemic, legislation was underway to make penalties for graffiti artists more severe, and restrictions on paint sale and display made obtaining materials difficult.[3]

Many graffiti artists, however, chose to see the new problems as a challenge rather than a reason to quit.[3] A downside to these challenges was that the artists became very territorial of good writing spots, and strength and unity in numbers (gangs) became increasingly important.[3] This was stated to be the end for the casual subway graffiti artists.

In 1984, the New York City Transit Authority (NYCTA) began a five-year program to eradicate graffiti. The years between 1985 and 1989 became known as the "diehard" era.[3] A last shot for the graffiti artists of this time was in the form of subway cars destined for the scrap yard.[3] With the increased security, the culture had taken a step back. The previous elaborate "burners" on the outside of cars were now marred with simplistic marker tags which often soaked through the paint.

By mid-1986, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) and the NYCTA were winning their "war on graffiti", with the last graffitied train removed from service in 1989.[2][3][11] As the population of artists lowered so did the violence associated with graffiti crews and "bombing".[3] However, teenagers from inner London and other European cities with family and other links to New York City had by this time taken up some of the traditions of subway Graffiti and exported them home, although New York City writers like Brim, Bio, and Futura had themselves played a significant role in establishing such links when they visited London in the early-to-mid-1980s and "put up pieces" on or near the western ends of the Metropolitan line, outside London.

Almost as significantly, just when subway graffiti was on the decline in New York City, some British teenagers who had spent time with family in Queens and the Bronx returned to London with a "mission" to Americanize the London Underground Limited (LUL) through painting New York City-style graffiti on trains. These small groups of London "train writers" (LUL writers) adopted many of the styles and lifestyles of their New York City forebears, painting graffiti train pieces and in general "bombing" the system, but favoring only a few selected underground lines seen as most suitable for train graffiti. Although on a substantially smaller scale than what had existed in New York City, graffiti on LUL rolling stock became seen as enough of a problem by the mid-1980s to provoke the British Transport Police to establish its own graffiti squad modeled directly on and in consultation with that of the MTA. At the same time, graffiti art on LUL trains generated some interest in the media and arts, leading to several art galleries putting on exhibitions of some of the art work (on canvass) of a few LUL writers as well as TV documentaries on London hip-hop culture like the BBC's Bad Meaning Good, which included a section featuring interviews with LUL writers and a few examples of their pieces.

Clean Train Movement era edit

The Clean Train Movement, wherein the rolling stock was either cleaned or outright replaced, started in 1985, with the last graffiti-covered train out of service by 1989.[2][3][11] With subway trains being increasingly inaccessible, other property became the targets of graffiti. Rooftops became the new billboards for some 1980s-era writers.[11] The current era in graffiti is characterized by a majority of graffiti artists moving from subway or train cars to "street galleries".[citation needed] Prior to the Clean Train Movement, the streets were largely left untouched not only in New York City, but in other major American cities as well.[citation needed] After the transit company began diligently cleaning their trains, graffiti burst onto the streets of America to an unexpecting and unappreciative public.[citation needed]

City officials elsewhere in the country smugly assumed that gang graffiti were a blight limited largely to the Big Apple [New York City]. The stylized smears born in the South Bronx have spread across the country, covering buildings, bridges and highways in every urban center. From Philadelphia to Santa Barbara, Calif., the annual costs of cleaning up after the underground artists are soaring into the billions.[12]

Meanwhile, in New York in 1995, Mayor Rudolph Giuliani set up the Anti-Graffiti Task Force,[13] a multi-agency initiative to combat graffiti in New York City. This began a crackdown on "quality-of-life crimes" throughout the city, and one of the largest anti-graffiti campaigns in U.S. history. That same year Title 10-117 of the New York Administrative Code banned the sale of aerosol spray-paint cans to children under 18. The law also requires that merchants who sell spray paint must either lock it in a case or display the cans behind a counter, out of reach of potential shoplifters. Violations of the city's anti-graffiti law carry fines of US$350 per incident.[14]

On January 1, 2006, in New York City, legislation created by Councilmember Peter Vallone, Jr. attempted to raise the minimum age for possession of spray paint or permanent markers from 18 to 21. The law prompted outrage by fashion and media mogul Marc Ecko who sued Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Councilmember Vallone on behalf of art students and "legitimate" graffiti artists. On May 1, 2006, Judge George B. Daniels granted the plaintiffs' request for a preliminary injunction against the recent amendments to the anti-graffiti legislation, effectively prohibiting the New York Police Department from enforcing the higher minimum age.[15] A similar measure was proposed in New Castle County, Delaware in April 2006[16] and passed into law as a county ordinance in May 2006.[17]

At the same time, graffiti has begun to enter mainstream.[2] Much controversy arose on whether graffiti should be considered an actual form of art.[2][3][18][19] In 1974, Norman Mailer published an essay, The Faith of Graffiti, that explores the question of graffiti as art and includes interviews from early subway train graffitists, and then New York City mayor, John Lindsey. Since the 1980s, museums and art galleries started treating graffiti seriously.[2] Many graffiti artists had taken to displaying their works in galleries and owning their own studios. This practice started in the early 1980s with artists such as Jean-Michel Basquiat, who started out tagging locations with his signature SAMO ("Same Old Shit"), and Keith Haring, who was also able to take his art into studio spaces. In some cases, graffiti artists had achieved such elaborate graffiti (especially those done in memory of a deceased person) on storefront gates that shopkeepers have hesitated to cover them up. In the Bronx after the death of rapper Big Pun, several murals dedicated to his life done by Bio, Nicer TATS CRU appeared virtually overnight;[20] similar outpourings occurred after the deaths of The Notorious B.I.G., Tupac Shakur, Big L, and Jam Master Jay.[21][22]

Media edit

- Stations of the Elevated (1981) – the earliest documentary about subway graffiti in New York City, with music by Charles Mingus

- Wild Style (1982) – a drama about hip hop and graffiti culture in New York City

- Style Wars (1983) – an early documentary on hip hop culture, made in New York City

- Bomb the System (2006) – a drama about a crew of graffiti artists in modern-day New York City

- Infamy (2007) – a feature-length documentary about graffiti culture as told through the experiences of six well-known graffiti writers and a graffiti buffer.

- New York, New York (1976) – an episode of the BBC documentary series Omnibus, telling the story of graffiti in New York, as told by New Yorkers themselves.

See also edit

References edit

Notes

- ^ Ross Russell. Bird Lives!: The High Life And Hard Times Of Charlie (Yardbird) Parker Da Capo Press.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "A History of Graffiti in Its Own Words". New York.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q About New York City Graffiti, part 1

- ^ a b Peter Shapiro, Rough Guide to Hip Hop, 2nd. ed., London: Rough Guides, 2007.

- ^ David Toop, Rap Attack, 3rd ed., London: Serpent's Tail, 2000.

- ^ Fab 5 Freddy quote in: Lippard, Lucy. Mixed Blessings: Art in Multicultural America. New York: The New Press, 1990.

- ^ a b David Grazian, "Mix It Up", W W Norton & Co Inc, 2010, ISBN 0-393-92952-3, p.14

- ^ a b Chronopoulos, Themis (2012). Spatial Regulation in New York City: From Urban Renewal to Zero Tolerance (illustrated ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 103. ISBN 978-1136740688.

- ^ Kelling, George L. (2009). "How New York Became Safe: The Full Story". City Journal. Retrieved November 24, 2009.

- ^ Glazer, Nathan (1979), "On Subway Graffiti in New York" (PDF), National Affairs, no. 54, pp. 3–12, archived from the original (PDF) on October 17, 2015, retrieved November 24, 2009

- ^ a b c About New York City Graffiti, part 2

- ^ Beaty, Jonathon & Cray, Dan (September 10, 1990). "Zap You've Been Tagged". Time. paragraph 2.

- ^ Anti-Graffiti Task Force

- ^ "The full text of the law".

- ^ "Marc Ecko Helps Graffiti Artists Beat NYC in Court, Preps 2nd Annual Save The Rhinos Concert". May 2, 2006. Archived from the original on November 19, 2010.

- ^ Reda, Joseph (April 25, 2006). "Bill/Resolution #O06037". County Council: Passed Legislation. Council of New Castle County, Delaware. Archived from the original on August 27, 2007. Retrieved May 24, 2006.

- ^ Staff (May 24, 2006). "NCCo OKs laws to keep spray paint from kids". The News Journal. p. B3.

- ^ "From graffiti to galleries". CNN. November 4, 2005. Retrieved October 10, 2006.

- ^ "Writing on the Wall". Time Out New York Kids. 2006. Archived from the original on November 13, 2006. Retrieved October 11, 2006.

- ^ "New Big Pun Mural To Mark Anniversary Of Rapper's Death in the late 1990s". MTV News. February 2, 2001. Retrieved October 11, 2006.

- ^ "Tupak Shakur". Harlem Live. Archived from the original on October 25, 2006. Retrieved October 11, 2006.

- ^ ""Bang the Hate" Mural Pushes Limits". Santa Monica News. Retrieved October 11, 2006.

Further reading

- Austin, Joe. Taking the Train: How Graffiti Art Became an Urban Crisis in New York City. New York: Columbia University Press. 2002

- Gladwell, Malcolm. The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference. Back Bay, Boston. 2002. pp. 142–143

- Kramer, Ronald. "Painting with Permission: Legal Graffiti in New York City". Ethnography 11, 2, (2010): 235-253

- Kramer, Ronald. "Moral Panics and Urban Growth Machines: Official Reactions to Graffiti in New York City, 1990–2005". Qualitative Sociology, 33, 3, (2010): 297-311

- Lachman, Richard. "Graffiti as Career and Ideology". American Journal of Sociology 94 (1988):229-250

External links edit

- Media related to Graffiti in New York City at Wikimedia Commons