Parts of this article (those related to 2012–present) need to be updated. (April 2016) |

Iran is an energy superpower and the petroleum industry in Iran plays an important part in it.[2][3][4] In 2004, Iran produced 5.1 percent of the world's total crude oil (3.9 million barrels (620,000 m3; 160 million US gal) per day), which generated revenues of US$25 billion to US$30 billion and was the country's primary source of foreign currency.[5][6] At 2006 levels of production, oil proceeds represented about 18.7% of gross domestic product (GDP). However, the importance of the hydrocarbon sector to Iran's economy has been far greater. The oil and gas industry has been the engine of economic growth, directly affecting public development projects, the government's annual budget, and most foreign exchange sources.[5]

In FY 2009, the sector accounted for 60% of total government revenues and 80% of the total annual value of both exports and foreign currency earnings.[citation needed] Oil and gas revenues are affected by the value of crude oil on the international market. It has been estimated that at the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) quota level (December 2004), a one-dollar change in the price of crude oil on the international market would alter Iran's oil revenues by US$1 billion.[5]

In 2012, Iran, which exported around 1.5 million barrels of crude oil a day, was the second-largest exporter among the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries.[7] In the same year, officials in Iran estimated that Iran's annual oil and gas revenues could reach $250 billion by 2015.[8] However, the industry was disrupted by an international embargo from July 2012 through January 2016.[9][10] Iran plans to invest a total of $500 billion in the oil sector before 2025.[11][12]

History edit

The era of international control, 1901–1979 edit

The history of Iran's oil industry began in 1901, when British speculator William D'Arcy received a concession from Iran to explore and develop southern Iran's oil resources. The exploration in Iran was led by George Reynolds. The discovery of oil on May 26, 1908[13] led to the formation in 1909 of the London-based Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC). By purchasing a majority of the company's shares in 1914, the British government gained direct control of the Iranian oil industry, which it would not relinquish for 37 years. After 1935 the APOC was called the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC). A 60-year agreement signed in 1933 established a flat payment to Iran of four British pounds for every ton of crude oil exported and denied Iran any right to control oil exports.[5]

In 1950 ongoing popular demand prompted a vote in the Majlis to nationalize the petroleum industry. A year later, the government of Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadeq formed the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC). A 1953 coup d'état led by British and U.S. intelligence agencies ousted the Mossadeq government and paved the way for a new oil agreement.[14][15] In 1954 a new agreement divided profits equally between the NIOC and a multinational consortium that had replaced the AIOC. In 1973 Iran signed a new 20-year concession with the consortium.[5]

Beginning in the late 1950s, many of Iran's international oil agreements did not produce the expected outcomes; even those oil companies that managed to extract oil in their designated areas contributed very little to the country's total oil production. By the time of the Islamic Revolution of 1978–79, the five largest international companies that had agreements with the NIOC accounted for only 10.4 percent of total oil production.[clarification needed] During this period, Iran's oil industry remained disconnected from other industries, particularly manufacturing. This separation promoted inefficiencies in the country's overall industrial economy.[5]

In 1973, at a time when Iran was the second-largest oil exporter in the world and the Arab–Israeli War of October 6–25 was pressurizing the price of oil, the Shah of Iran told the New York Times,[16] "Of course the world price of oil is going to rise. ... Certainly! And how ...; You [Western nations] increased the price of wheat you sell us by 300%, and the same for sugar and cement ...; You buy our crude oil and sell it back to us, refined as petrochemicals, at a hundred times the price you've paid to us ...; It's only fair that, from now on, you should pay more for oil. Let's say ten times more."

The era of nationalized oil, 1979–present edit

Isolation and stagnation under Khomeini edit

Following the Revolution, the NIOC took control of Iran's petroleum industry and canceled Iran's international oil agreements. In 1980 the exploration, production, sale, and export of oil were delegated to the Ministry of Petroleum. Initially Iran's post-revolutionary oil policy was based on foreign currency requirements and the long-term preservation of the natural resource. Following the Iran–Iraq War, however, this policy was replaced by a more aggressive approach: maximizing exports and accelerating economic growth. From 1979 until 1998, Iran did not sign any oil agreements with foreign oil companies.

Khatami era edit

Early in the first administration of President Mohammad Khatami (in office 1997–2005), the government paid special attention to developing the country's oil and gas industry. Oil was defined as inter-generational capital and an indispensable foundation of economic development. Thus, between 1997 and 2004 Iran invested more than US$40 billion in expanding the capacity of existing oil fields and discovering and exploring new fields and deposits. These projects were financed either in the form of joint investments with foreign companies or domestic contractors or through direct investment by the NIOC. In accordance with the law, foreign investment in oil discovery was possible only in the form of buyback agreements under which the NIOC was required to reimburse expenses and retain complete ownership of an oil field. Marketing of crude oil to potential buyers was managed by the NIOC and by a government enterprise called Nicoo. Nicoo marketed Iranian oil to Africa, and the NIOC marketed to Asia and Europe.[5] According to IHS CERA estimate, oil revenue of Iran will increase by a third to USD 100 billion in 2011 even though the country is under an extended period of U.S. sanctions.[17]

Post-JCPOA era edit

The signing of the JCPOA in July 2015 by Hassan Rouhani and Javad Zarif with Barack Obama heralded a new era of détente in foreign relations. With it, Iran was allowed to come in from the cold, as it were and once again to sell its oil unencumbered on the world stage. The withdrawal by Donald Trump from the JCPOA in May 2018 was an ill wind for Iran because he decided to re-apply the sanctions regime that had caused such difficulties to Khamenei. For example, the Grace 1 oil tanker was captured near Gibraltar in July 2019 at the request of the US by the armed forces of the UK. The incident was one of several that have been labelled as the 2019 Persian Gulf crisis, but the crisis soon widened to encompass more distant seas where Iranian arms are impotent. In May the Iranian tanker Happiness 1 suffered difficulties near Jiddah. In August the tanker Helm encountered difficulties while transiting the Red Sea, and in October the Iranian tanker Sabiti was attacked by two missiles of unknown origin, again in the Red Sea.[18] The fully laden Sabiti had been destined for the "Eastern Mediterranean".[19]

China is a significant supporter of the Iranian petroleum industry. In 2017, 64% of an export total $16.9 billion with China was labelled "crude oil".[20] Because the National Iranian Tanker Company cannot defend the product on the oceans, it most often leaves port under the flag of another nation which is able to defend its own interests.[21] The case of a Shanghai-based operator of oil tankers, Kunlun Holdings is illustrative: in early June it was operating with a shipment of Iranian crude oil as the Pacific Bravo before its transponder disappeared on 5 June in the Straits of Malacca. When it reappeared on 18 July, the ship had been relieved of its load and had been renamed to become the Latin Venture. The US, which had warned ports not to offload the $120 million cargo of the Pacific Bravo, was unhappy about the failure of its sanctions regime.[22] Kunlun Holdings is owned by the Bank of Kunlun, which is in turn owned by the (SOE) CNPC. The Bank "has long been the financial institution at heart of China-Iran bilateral trade".[23] Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson Geng Shuang "resolutely opposes" American unilateral sanctions.[24]

Oil production and reserves edit

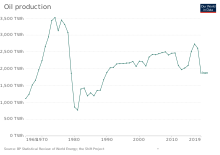

Total oil production reached a peak level of 6.6 Mbbl/d (1,050,000 m3/d) in 1976. By 1978, Iran had become the second-largest OPEC producer and exporter of crude oil and the fourth-largest producer in the world. After a lengthy decline in the 1980s, production of crude oil began to increase steadily in 1987. In 2008 Iran produced 3.9-million-barrels (620,000 m3) per day (bpd) and exported 2.4 Mbbl/d (380,000 m3/d).[25] Accounting for 5 percent of world production, it returned to its previous position as OPEC's second-largest producer. According to estimates, in 2005 Iran had the capacity to produce 4.5 Mbbl/d (720,000 m3/d); it was believed that production capacity could increase to 5 Mbbl/d (790,000 m3/d) to 7 Mbbl/d (1,100,000 m3/d), but only with a substantial increase in foreign investment.[26] Iran's long-term sustainable oil production rate is estimated at 3.8 Mbbl/d (600,000 m3/d).[5] According to the Iranian government, Iran has enough reserves to produce oil for the next 100 years while oil reserves of other Middle Eastern countries will be depleted in the next 60 years and most other oil-rich countries will lose their reserves within the next 30 years.[citation needed]

In 2006 Iran reported crude oil reserves of 132.5 billion barrels (2.107×1010 m3), accounting for about 15 percent of OPEC's proven reserves and 11.4 percent of world proven reserves. While the estimate of world crude oil reserves remained nearly steady between 2001 and 2006, at 1,154 billion barrels (1.835×1011 m3), the estimate of Iran's oil reserves was revised upward by 32 percent when a new field was discovered near Bushehr. Market value of Iran's total oil reserves at international crude price of $75 per barrel stands at ~US $10 trillion.[27]

In the early 2000s, leading international oil firms from China, France, India, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Russia, Spain, and the United Kingdom had agreements to develop Iran's oil and gas fields. In 2004 China signed a major agreement to buy oil and gas from Iran, as well as to develop Iran's Yadavaran oil field. The value of this contract was estimated at US$150 billion to US$200 billion over 25 years.[5][28] In 2009, China National Petroleum Corp (CNPC) signed a deal with the National Iranian Oil Company whereby the former took ownership of a 70% stake upon promising to pay 90 percent of the development costs for the South Azadegan oil field, with the project needing investment of up to $2.5 billion. Earlier that year, CNPC also won a $2 billion deal to develop the first phase of the North Azadegan oilfield.[29]

A more modest yet important agreement was signed with India to explore and produce oil and natural gas in southern Iran. In 2006 the rate of production decline was 8 percent for Iran's existing onshore oil fields (furnishing the majority of oil output) and 10 percent for existing offshore fields. Little exploration, upgrading, or establishment of new fields occurred in 2005–6.[5] However, the threat of American retaliation kept the investment way below the desired levels.[30] It only allowed Iran to continue to keep its oil export at or below its OPEC determined quota level.[31][32] Today, much of the equipment needed for oil industry are being produced by local manufacturers in Iran.[citation needed] Besides, Iran is among the few countries that has reached the technology and "know-how" for drilling in the deep waters.[33]

Oil refining and consumption edit

In 2011 Iran's refineries had a combined capacity of 1.457 Mbbl/d (231,600 m3/d). The largest refineries have the following capacities: Abadan, 350,000 bbl/d (56,000 m3/d); Esfahan, 284,000 bbl/d (45,200 m3/d); Bandar-e Abbas, 232,000 bbl/d (36,900 m3/d); Tehran, 220,000 bbl/d (35,000 m3/d); Arak, 170,000 bbl/d (27,000 m3/d); and Tabriz, 100,000 bbl/d (16,000 m3/d).[34] In 2004 pipelines conveyed 69 percent of total refined products; trucks, 20 percent; rail, 7 percent; and tankers, 4 percent. Oil refining produces a wide range of oil products, such as liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), gasoline, kerosene, fuel oil, and lubricants.[5] As of 2011[update] Iran is a net exporter of petroleum products thanks to large exports of residual fuel oil, but the refineries cannot meet domestic demand for lighter distillates such as gasoline.[34]

Between 1981 and 2010, domestic consumption of oil products increased from 0.6 Mbbl/d (95,000 m3/d) to 1.8 Mbbl/d (290,000 m3/d)[34]—an average annual growth rate of 3.7 percent. Between 1981 and 2004, consumption of gasoline grew by 6 percent annually, but domestic production met only 75 percent of demand for this product. In 2004 the country imported US$1.6 billion worth of gasoline. By 2006 it imported 41 percent of its gasoline, but by 2010 imports were down to 19.5% of gasoline consumption[34] and heavy investment in new refining capacity may see Iran exporting gasoline by 2015.[34] Refining capacity increased 18% in 2010 and the target is to increase refining capacity to 3.5 million barrels per day.[35]

Trade in oil and oil products edit

In 2006 exports of crude oil totaled 2.5 Mbbl/d (400,000 m3/d), or about 62.5 percent of the country's crude oil production. The direction of crude oil exports changed after the Revolution because of the U.S. trade embargo on Iran and the marketing strategy of the NIOC. Initially, Iran's post-revolutionary crude oil export policy was based on foreign currency requirements and the need for long-term preservation of the natural resource. In addition, the government expanded oil trade with other developing countries. While the shares of Europe, Japan, and the United States declined from an average of 87 percent of oil exports before the Revolution to 52 percent in the early 2000s, the share of exports to East Asia (excluding Japan) increased significantly. In addition to crude oil exports, Iran exports oil products. In 2006 it exported 282,000 barrels (44,800 m3) of oil products, or about 21 percent of its total oil product output.[36] Iran plans to invest a total of $500 billion in the oil sector before 2025.[11][dead link][12]

In 2010, Iran, which exports around 2.6 million barrels of crude oil a day, was the second-largest exporter among the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries.[37] Several major emerging economies depend on Iranian oil: 10% of South Korea's oil imports come from Iran, 9% of India's and 6% of China's.[17] Moreover, Iranian oil makes up 7% of Japan's and 30% of all Greece's oil imports.[17] Iran is also a major oil supplier to Spain and Italy.[37] In the same year, officials in Iran estimate that Iran's annual oil and gas revenues could reach $250 billion by 2015 once the current projects come on stream.[8]

According to IHS CERA estimate, oil revenue of Iran will increase by a third to USD 100 billion in 2011 even though the country is under an extended period of U.S. sanctions.[17] As of January 2012, Iran exports 22% of its oil to China, 14% to Japan, 13% to India, 10% to South Korea, 7% to Italy, 7% to Turkey, 6% to Spain and the remainder to France, Greece (& other European countries), Taiwan, Sri Lanka, South Africa.[38]

In 2020 exports of petrochemicals and petroleum products were worth almost $20 billion.[39]

-

Iran crude oil and condesate exports for key countries.

Pipeline transport edit

According to the Global Energy Monitor website, the top five countries in terms of developing pipelines (proposed and under construction) are the United States, India, Iraq, Iran, and Tanzania. Iran has ranked first in terms of oil pipelines under construction. Ministry of Petroleum Iran is among the five parent companies developing oil pipelines.[40][41]

Natural gas edit

In addition to the natural gas associated with oil exploration and extraction, an estimated 62 percent of Iran's 32.3 trillion cubic meters of proven natural gas reserves in 2006 were located in independent natural gas fields, an amount second only to those of Russia.[44] In 2006 annual production reached 105 billion cubic meters, with fastest growth occurring over the previous 15 years. In 2006 natural gas accounted for about 50 percent of domestic energy consumption, in part because domestic gas prices were heavily subsidized.[36] Natural gas production will reach 700 million cubic meter/day by 2012[45] and 900 million cubic meter/day by 2015.[citation needed]

Since 1979, infrastructure investment by Iranian and foreign oil firms has increased pipeline[46] capacity to support the Iranian gas industry. Between 1979 and 2003, pipelines to transport natural gas to refineries and to domestic consumers increased from 2,000 kilometers to 12,000 kilometers. In the same period, natural gas distribution pipelines increased from 2,000 kilometers to 45,000 kilometers in response to growing domestic consumption. Gas processing plants are located at Ahvaz, Dalan, Kangan, and Marun, in a corridor along the northern Persian Gulf close to the major gas fields. South Pars, Iran's largest natural gas field, has received substantial foreign investment. With its output intended for both export and domestic consumption, South Pars is expected to reach full production in 2015. However, delays and lower production in the Iranian side due to sanctions is resulting in migration of gas to the Qatari part and a loss for Iran.[47]

The output of South Pars is the basis of the Pars Special Economic Energy Zone, a complex of petrochemical and natural gas processing plants and port facilities established in 1998 on the Persian Gulf south of Kangan.[36] Iran is able to produce all the parts needed for its gas refineries.[48] Iran is now the third country in the world to have developed gas to liquids (GTL) technology.[49]

In the 1980s, Iran began to replace oil, coal, charcoal, and other fossil-fuel energy sources with natural gas, which is environmentally safer. The share of natural gas in household energy consumption, which averaged 54 percent in 2004, was projected to increase to 69 percent by 2009. Overall, natural gas consumption in Iran was expected to grow by more than 10 percent per annum between 2005 and 2009.[36]

With international oil prices increasing and projected to continue increasing, international demand for natural gas and investment in production and transportation of natural gas to consumer markets both increased in the early 2000s. Iran set a goal of increasing its natural gas production capacity to 300 billion cubic meters by 2015 while keeping oil production stable.[50] To achieve this capacity, the government has planned a joint investment worth US$100 billion in the oil and gas industry through 2015.

Market value of Iran's total natural gas reserves at comparative international energy price of $75 per barrel of oil stands at ~US $4 trillion.[51] Following the discovery of a large gas deposit in the Caspian sea (The Sardar Jangal gas field) in 2011 estimated at 50 trillion cubic feet (some 1.4 trillion cubic meters), Iran could rank first in the world in terms of gas reserves.[52][53] In addition, Iranian media have reported in 2012 the discovery of gas field "as big as South Pars gas field" in the oil-rich Khuzestan province.[54] In 2011, Iran signed a contract with Baghdad and Damascus in order to export Iran's gas to Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, the Mediterranean region and eventually Europe.[55] Oman and Kuwait were negotiating an import agreement in 2014.[56] Once all pipelines become operational, Iran can potentially export a total of more than 200 million cubic meter of natural gas every year to Iraq, India, Pakistan, and Oman.[57]

Major foreign projects edit

In 2004 Iran signed a contract with France and Malaysia for production and export of natural gas and another agreement with European and Asian companies for expansion and marketing of its natural gas resources. In 2005 Iran exported natural gas to Turkey and was expected to expand its market to Armenia, China, Japan, other East Asian countries, India, Pakistan, and Europe. The first section of a new line to Armenia opened in spring 2007, as a much-discussed major pipeline to India and Pakistan remained in the negotiation stage.[36]

Among some more recent deals, Switzerland's energy company EGL, signed a 25-year LNG export deal with Iran's National Iranian Gas Export Company on March 17, 2007, reportedly valued at 18 billion. Switzerland will buy 5.5 billion cubic meters of Iranian natural gas each year, beginning in 2011. In April 2007, OMV, the Austrian partially state-owned energy company, signed letters of intent with Iran, worth an estimated $22.8 billion (22 billion euros), for Iran to supply Europe with gas. The United States has expressed strong opposition to both the Swiss and Austrian deals with Iran.[58]

The National Iranian Gas Company (NIGC) is expected to finalize a natural gas export deal with Pakistan, with exports set to begin in 2011. The gas would be transported through a "Peace pipeline", worth about $7.4 billion. The plan initially also included exporting gas to India, but negotiations have stalled over pricing. Iran also is discussing a gas production and export deal with Turkey. Under the plan, Turkey would assist in developing Iran's South Pars field in exchange for cash or natural gas. Gas would be shipped from Iran to Turkey and Europe via a new pipeline that Turkey plans to build.[58]

Other notable petroleum sector development deals include those with Russia and China. On February 19, 2008, Russian state gas company Gazprom announced a deal to establish a joint venture company to develop the offshore Iranian South Pars gas field. A China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) investment deal, valued at $16 billion, to develop Iran's North Pars gas field and to build a liquid natural gas (LNG) plant, was supposed to be signed on February 27, 2008 but has been delayed.[59] The state-operated National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) and CNOOC signed a memorandum of understanding in December 2006 for the project, under which CNOOC would purchase 10 million metric tons per year of LNG for 25 years.[58]

Petrochemicals edit

In the early 2000s, an ambitious state petrochemicals project called for expansion of annual output in that industry from 9 million tons in 2001 to 100 million tons in 2015.[60] Output capacity in 2006 was estimated at 15 million tons. The goal of this expansion is to increase the percentage of Iran's processed petroleum-based exports, which are more profitable than raw materials. In 2005 Iran exported US$1.8 billion of petrochemical products (about one-third of total nonoil exports in that year). Receiving 30 percent of Iran's petrochemical exports between them, China and India were the major trading partners in this industry. Iran's domestic resource base gives it a unique comparative advantage in producing petrochemicals when international crude oil prices rise. The gain has been greatest in those plants that use liquid gas as their main input. For FY 2006, the petrochemical industry's share of GDP was projected to be about 2 percent.[61] Iran plans to invest a total of $500 billion in the oil sector before 2025.[11][dead link][12]

Iran's petrochemical industries have absorbed a large amount of private and public investment. In the early 2000s, 43 percent of these investments was financed by Iran's National Petrochemical Company, a subsidiary of the Ministry of Petroleum, which administers the entire petrochemical sector. Another 53 percent is owned by foreign creditors (more than 100 foreign banks and foreign companies), 3 percent by banks, and 1 percent by the capital market. Most of the petrochemical industry's physical capital is imported, and the industry does not have strong backward linkages to manufacturing industries. In 2006 new petrochemical plants came online at Marun and Asaluyeh, and construction began on three others.[61] Iran National Petrochemical Company's output capacity will increase to over 100 million tpa by 2015 from an estimated 50 million tpa in 2010 thus becoming the world' second largest chemical producer globally after Dow Chemical with Iran housing some of the world's largest chemical complexes.[62][63]

See also edit

- Energy in Iran

- Economy of Iran

- Industry of Iran

- Iranian Oil Bourse

- Ministry of Petroleum of Iran

- National Iranian Oil Company

- National Iranian Oil Refining and Distribution Company

- National Iranian Petrochemical Company

- National Iranian Gas Company

- Tehran Stock Exchange

- Iranian targeted subsidy plan

References edit

- ^ SHANA: Share of domestically made equipments on the rise Archived 2012-03-09 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- ^ Energy and the Iranian economy. DIANE. July 25, 2006. ISBN 9781422320945. Archived from the original on April 7, 2016. Retrieved April 14, 2016.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|agency=ignored (help) - ^ Bezen, Balamir Coşkun (2009). "Global Energy Geopolitics and Iran" (PDF). Uluslararası İlişkiler. 5 (20): 179–201. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-04-01. Retrieved 2016-10-29.

- ^ "The Rising might of the Middle East super power - Council on Foreign Relations". Cfr.org. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2012-02-07.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Kurtis, Glenn; Eric Hooglund. Iran, a country study. Washington D.C.: Library of Congress. pp. 160–163. ISBN 978-0-8444-1187-3. Retrieved November 21, 2010. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Iran's Foreign Trade Regime Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-03-10. Retrieved 2010-08-11.

- ^ "Sanctions reduced Iran's oil exports and revenues in 2012". EIA. Apr 26, 2013. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- ^ a b Mehr News Agency: Iran eyes $250 billion annual revenue in 5 years Archived 2018-07-17 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved December 22, 2010

- ^ Nasseri, Ladane (12 February 2012). "Iran Won't Yield to Pressure, Foreign Minister Says; Nuclear News Awaited". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 23 December 2014. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ Chuck, Elizabeth (16 January 2016). "Iran Sanctions Lifted After Watchdog Verifies Nuclear Compliance". Reuters. Archived from the original on 23 March 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ a b c Iran Daily - Domestic Economy - 04/24/08 [dead link]

- ^ a b c Ariel Cohen, James Phillips and Owen Graham (Feb 14, 2011). "Iran's Energy Sector: A Target Vulnerable to Sanctions". The Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on January 10, 2012. Retrieved December 20, 2011.

- ^ The Iranian Petroleum Institute (1971). Oil in Iran. p. 14. ASIN B000YBGZ54.

- ^ Kinzer, All the Shah's Men: An American Coup and the Roots of Middle East Terror (John Wiley & Sons, 2003), p.166

- ^ The Ford Presidency: A History, by Andrew Downer Crain, p.124

- ^ Smith, William. D. "Price Quadruples for Iranian Crude Oil at Auction", New York Times December 12, 1973

- ^ a b c d Yadullah Hussain (Dec 19, 2011). "Sanctions against Iran could trigger oil price spike". National Post. Archived from the original on March 2, 2015. Retrieved Dec 20, 2011.

- ^ "Tehran says Iranian oil tanker struck by missiles off coast of Saudi Arabia". The Globe and Mail Inc. The Associated Press. 11 October 2019. Archived from the original on 12 October 2019. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- ^ "Iran says two missiles hit one of its oil tankers in the Red Sea near Saudi Arabia". National Post, a division of Postmedia Network Inc. Bloomberg News. 11 October 2019.

- ^ "What does Iran export to China? (2017)". Observatory of Economic Complexity. Archived from the original on 2019-10-13. Retrieved 2019-10-13.

- ^ "To Evade Sanctions on Iran, Ships Vanish in Plain Sight". The New York Times. 2 July 2019. Archived from the original on 11 September 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- ^ "For 42 days, its transponder was deactivated. And then 'Pacific Bravo' vanished". National Post. 16 August 2019.

- ^ "A single oil tanker could become a factor in both the China trade war and Iran tensions". CNBC LLC. A Division of NBCUniversal. 30 May 2019. Archived from the original on 19 September 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- ^ Batmanghelidj, Esfandyar (17 May 2019). "China Restarts Purchases of Iranian Oil, Bucking Trump's Sanctions". CCI Ltd. Bourse & Bazaar. Archived from the original on 13 October 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- ^ Energy Information Administration: Iran's entry Archived 2008-03-31 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved November 21, 2010

- ^ How Iran could double its oil output Archived 2016-03-07 at the Wayback Machine. CNN. Retrieved June 3, 2012.

- ^ "Interview: Iran to Cut Oil Subsidies in Energy Reform". IMFSurvey Magazine. International Monetary Fund. September 28, 2010. Archived from the original on 7 October 2010. Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- ^ Wolfensberger, Marc (November 25, 2006). "Iran Invites Sinopec Head to Sign $100 Billion Oil, Gas Deals". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 6 February 2007. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

- ^ Iran Investment Monthly - September 2011 Archived 2016-06-02 at the Wayback Machine. Turquoise Partners. Retrieved November 3, 2011.

- ^ US Department of the Treasury: An overview of O.F.A.C. Regulations involving Sanctions against Iran Archived 2010-10-24 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved November 21, 2010

- ^ Schweid, Barry (December 25, 2006). "Iran's Oil Exports May Disappear". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 11, 2012. Retrieved November 21, 2010.

- ^ "Sanctions put choker on Iran oil exports". Financial Times. Archived from the original on September 15, 2010. Retrieved November 21, 2010.

- ^ Oil Minister: Iran Self-Sufficient in Drilling Industry Archived 2013-06-06 at the Wayback Machine. Fars News Agency. Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e "Country Analysis Briefs - Iran". Energy Information Administration. November 2011. Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- ^ Mathew, Shaji (9 November 2011). "Iran Refining Capacity to Reach 3.5 Million Barrels, Shana Says". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 2014-12-31. Retrieved 2017-03-11.

- ^ a b c d e Kurtis, Glenn; Eric Hooglund. Iran, a country study. Washington D.C.: Library of Congress. pp. 163–166. ISBN 978-0-8444-1187-3. Retrieved November 21, 2010. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b Jay Solomon (Dec 19, 2011). "U.S., Allies Step Up Iran Embargo Talks". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on April 11, 2017. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- ^ Iran's oil exports Archived 2016-07-25 at the Wayback Machine. New York Times. Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ^ Sharafedin, Bozorgmehr; Tan, Florence (17 September 2021). "Iran's petrochemical, fuel sales boom as sanctions hit crude exports". Reuters. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ^ "Half of the world's oil pipelines under construction are in Africa and the Middle East". 8 May 2023.

- ^ Krishnamurthy, Rohini (11 May 2023). "India among top 5 countries developing oil pipelines, 49% of projects in Africa and Middle East: Report".

- ^ US Department of Energy - Iran's entry Archived 2008-03-31 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved February 4, 2011.

- ^ US Department of Energy/Iran/Natural Gas Archived 2010-11-02 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved February, 2011.

- ^ "Country Comparison:: Oil - proved reserves". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 4 June 2010. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

- ^ Moj news: Iran to Raise Gas Output Capacity to 700 mln cum in 2012 Archived 2012-08-25 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved April 5, 2011

- ^ "IPS-M190-2: 4 Line Pipe Standard Similar to API 5L". HYSP Steel Pipe. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2014-11-21.

- ^ Bahman Aghai Diba: Is Qatar plundering Iran's share in the South Pars joint gas field? Archived 2014-07-04 at the Wayback Machine. Payvand.com, June 19, 2014. Retrieved June 19, 2014.

- ^ http://www.zawya.com/story.cfm/sidZAWYA20110531043119/SelfSufficiency_in_Refinery_Parts_Production_in_Iran.Zawaya. Retrieved February 4, 2012.

- ^ Iran, Besieged by Gasoline Sanctions, Develops GTL to Extract Gasoline from Natural Gas Archived 2012-02-07 at the Wayback Machine. Oil Price.com. Retrieved February 4, 2012.

- ^ Marinho, Helder (2009-10-07). "Iran Says It Is Ready for Foreign Energy Investment (Update2)". Bloomberg. Retrieved 2010-10-08.

- ^ "Iran to Cut Oil Subsidies in Energy Reform". IMFSurvey Magazine. International Monetary Fund. September 28, 2010. Archived from the original on 7 October 2010. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- ^ Iran's Sardar Jangal gas field in Caspian Sea to yield 880,000bpd Archived 2012-09-15 at archive.today. Mehr News Agency. Retrieved January 19, 2012

- ^ Iran finds large oil deposit in Caspian Sea Archived 2012-05-18 at the Wayback Machine. Mehr News Agency. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- ^ Iran Finds 'One of the Biggest' Gas Fields in Mideast, Mehr Says Archived 2014-06-05 at the Wayback Machine. Bloomberg LLP. Retrieved June 6, 2012.

- ^ Iran Investment Monthly - July 2011 Archived 2011-11-19 at the Wayback Machine Turquoise Partners. Retrieved September 19, 2011

- ^ Anthony Dipaola (2 June 2014). "Kuwait Wants to Buy Iran Gas as Energy Ties Trump Nuclear Fears". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 4 June 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ^ Iran Investment Monthly (December 2014) Archived 2015-02-26 at the Wayback Machine. Turquoise Partners. Retrieved February 25, 2015.

- ^ a b c Ilias, Shayerah (2008). Iran's Economy (PDF) (Report). Congressional Research Service. pp. 17–18. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-06-27. Retrieved 2017-06-25. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ BENOîT FAUCON And SPENCER SWARTZ (2010-08-12). "Iran Curbs LNG-Export Ambitions - WSJ.com". Online.wsj.com. Archived from the original on 2015-02-26. Retrieved 2010-10-08.

- ^ "Iran to build 46 new petchem units". Tehran Times. 2010-01-13. Archived from the original on 2011-06-13. Retrieved 2010-10-08.

- ^ a b Kurtis, Glenn; Eric Hooglund. Iran, a country study. Washington D.C.: Library of Congress. pp. 166–167. ISBN 978-0-8444-1187-3. Retrieved November 21, 2010. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "NPC Iran will be second largest commodity chemical producer in the world by 2015". Business Credit. 2006-06-01. Archived from the original on February 21, 2009. Retrieved 2016-04-14.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Iran to build 46 new petchem units". tehran times. 12 January 2010. Archived from the original on 2011-06-13. Retrieved 2012-02-07.

External links edit

- Ministry of Petroleum Of Iran Official Website

- Ministry of Energy Of Iran Official Website

- US Department of Energy - Iran's entry

- SHANA - Official News Service for Oil and Gas in Iran

- Oil & Gas Industry in Iran - 2003 Study (history, market overview, domestic suppliers, major projects, buy-backs)

- FACTBOX-Iran's crude export and fuel import customers - Reuters

- Offshore Middle East and Caspian Sea Oil and Gas Market Report 2011

- Iran Gas Markets Report, 2011 - GlobalData

- Iran's oil exportation map by country Archived 2012-01-28 at the Wayback Machine

- Iran oil sanctions calculator - Reuters

- Infrastructure map of Iran's fields and facilities

- Persia Land of Black Gold

- Iranian Discoveries Continue