Peter Greste (Latvian: Pēteris Greste; born 1 December 1965)[4] is a dual citizen Latvian Australian academic, memoirist and writer.[5][6] Formerly a journalist and foreign correspondent, he worked for Reuters, CNN, the BBC and Al Jazeera English; predominantly in the Middle East, Latin America and Africa.

Peter Greste | |

|---|---|

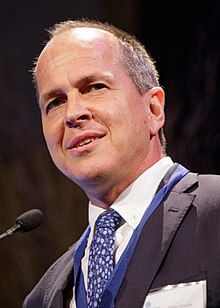

Greste in 2015 | |

| Born | 1 December 1965 Sydney, Australia[1] |

| Nationality | Latvian Australian |

| Citizenship | Australia Latvia |

| Education | Bachelor of Business[2] |

| Alma mater | Queensland University of Technology (Australia) |

| Occupation(s) | Academic, journalist, writer[3] |

| Notable work | Freeing Peter (2016) The First Casualty (2017) |

| Criminal status | Arrested and jailed in Cairo, Egypt on 29 December 2013 and sentenced for 7 years on 23 June 2014 Deported to Australia on 1 February 2015 to face prison or trial (Australia did not uphold) Egyptian retrial in absentia on 29 August 2015 increased jail sentence by another 3 years (Greste did not return to Egypt) |

| Conviction(s) | Falsifying news and having a negative impact on overseas perceptions of Egypt |

| Criminal penalty | 10 years prison (2013-23) 400 days served (2013-15) |

On 29 December 2013, Greste and two other Al Jazeera journalists were arrested by Egyptian authorities in Cairo.[7] On 23 June 2014, Greste was found guilty of falsifying news and having a negative impact on overseas perceptions of the country,[8] and sentenced to seven years prison.[9] The Australian government intervened and negotiated on his behalf with a new Egyptian government.[10]

On 1 February 2015, Greste was officially deported to Australia (via Cyprus) on the condition that he face prison or trial in his home country; something Australia did not uphold.[11] At a retrial on 29 August 2015, an Egyptian court sentenced Greste in absentia to another three years in prison. However, he avoided serving that sentence because he was already out of Egypt and did not return.[12] If the full sentences were served, Greste would have been incarcerated until December 2023.

Early life edit

Greste has Latvian ancestry and two younger brothers.[13][1] Born in Sydney, he is a dual citizen of Australia and Latvia.[14] Greste was school captain of Indooroopilly State High School,[15] and holds a Bachelor of Business degree from the Queensland University of Technology in Brisbane.[16][13]

Early news media career edit

From 1991 to 1995, Greste was based in London, Bosnia and South Africa, working for Reuters, CNN, WTN and the BBC. In 1995, he was based in Kabul, Afghanistan as a correspondent for the BBC and Reuters. Then, in Belgrade for a year as a correspondent for Reuters. Greste returned to London and worked for BBC News 24. He was next based in Mexico, then Santiago as a correspondent for the BBC.[17]

Greste returned to Afghanistan in 2001 to cover the start of the War in Afghanistan . Afterwards, he worked across the Middle East and Latin America. From 2004, Greste was based in Mombasa, Kenya, then Johannesburg, South Africa, followed by six years in Nairobi, Kenya.

In 2011, Greste won a Peabody Award for a BBC documentary on Somalia. That year, he left the BBC and became a correspondent for Al Jazeera English in Africa.[18][19]

Egyptian trial and imprisonment edit

In late December 2013, Greste was arrested in Cairo with Al Jazeera colleagues Mohamed Fadel Fahmy and Baher Mohamed.[20] "The interior ministry said the journalists had held illegal meetings with the Muslim Brotherhood", which was recently declared a terrorist group; furthermore, the journalists were accused of news reporting which was "damaging to national security".[21][22] In January 2014, Egyptian authorities were reportedly going to charge twenty Al Jazeera journalists, including Greste, of falsifying news and having a negative impact on overseas perceptions of the country.[8] The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights urged Egypt to "promptly release" the Al Jazeera personnel in custody.[23]

On 21 February 2014, Greste was refused bail and his case was adjourned until 5 March.[24] During a 31 March hearing, Greste asked to be released[7] and told the judge that "The idea that I could have an association with the Muslim Brotherhood is frankly preposterous."[7] On 23 June, Greste was found guilty and sentenced to seven years in prison. Mohammed Fahmy also received seven years while Baher Mohamed received ten years.[25] International media reaction was swift and negative. US Secretary of State John Kerry described the prison sentences as "chilling and draconian" and noted that he had spoken to Egyptian governmental officials including President Abdul Fattah al-Sisi.[26] Despite widespread international media condemnation, al-Sisi declared that he would not interfere with judicial rulings.[27]

Internationally, Greste and his colleagues were portrayed as political prisoners due to the nature of the trial, the evidence presented and the sentences imposed.[28] On the other hand, "Cairo felt that the Qatari media outlet (Al Jazeera) had become a mouthpiece for the ousted and banned Muslim Brotherhood. The harsh sentences were handed down as a warning to the Gulf state to not get involved in Egyptian domestic politics."[29] On 1 January 2015, the Court of Cassation announced a retrial for Greste and his colleagues. Release on bail was not permitted.[30] The Australian government intervened, and Greste was officially deported to Australia (via Cyprus) on 1 February. The Egyptian law allowing the deportation of foreigners stipulated that they face prison or trial in their home country, but Australia did not uphold either.[31] Otherwise, no explanation was given for his release.[32]

On 29 August 2015, an Egyptian court sentenced Greste and his two colleagues to another three years in prison, with Baher Mohamed receiving an additional six months. Greste was tried in absentia and avoided imprisonment because he was deported to Australia in February and did not re-enter Egypt.[33] On 23 September, Fahmy and Mohamed were pardoned by Egyptian President al-Sisi.[34]

Awards edit

Greste won a Peabody Award for a BBC documentary on Somalia in 2011. Two weeks after being released from prison and deported from Egypt in February 2015, Greste accepted a special Royal Television Society award in London on behalf of himself and two Al Jazeera colleagues for sacrifices to journalism.[35] After separately advocating widely for freedom of the press and free speech, Greste was individually awarded the 2015 Australian Human Rights Medal.[36]

Books edit

In 2016, Penguin Books published Freeing Peter, Greste's biographical account of his family's efforts to free him from an Egyptian prison.[37] Greste's next book, The First Casualty (2017), was shortlisted for the 2018 Walkley Book Award[38] and reportedly contains a "first-hand account of how the war on journalism has spread from the battlefields of the Middle East to the governments of the West".[39][40]

Later media career and academia edit

Greste wrote, directed and featured as interviewer in Facebook: Cracking the Code (2017), a forty-five minute Australian Four Corners television documentary. The episode's theme was the "lack of online privacy and the lengths the tracking goes to", "but that soon was usurped by Greste’s personal story of how his supporters used Facebook's algorithms to help spread his own story to mass markets and help his case" in Egypt rather than "how extreme right-wing supporters use similar methods and how they skirt Facebook's tracking system."[41][42][43][44][45]

Greste next presented Monash and Me (2018), a two-part TV documentary miniseries on the heroics of Australian First World War military commander Sir John Monash.[46] "While examining the battles that made Monash famous, Greste also discovered his own family’s previously unknown role in Monash’s First Australian Imperial Force."[47]

In February 2018, Greste was appointed UNESCO Chair in Journalism and Communications at the University of Queensland; a role that "includes a range of teaching, research and engagement activities".[48] With Australian lawyer Chris Flynn and journalist Peter Wilkinson, Greste co-founded the Alliance for Journalists' Freedom.[49] In April 2019, Greste denounced UK-imprisoned Australian editor, publisher and activist Julian Assange as a journalist and WikiLeaks as a news organisation.[50]

In 2022, Greste commenced as an adjunct professor of journalism at Macquarie University.[51]

Personal life edit

In 2021, the State Library of Queensland commissioned a digital story and an oral history interview with Greste.[52] As at late 2022, Greste identified as a keen kitesurfer living in Brisbane.[53] His partner, Christine Jackman,[54] is also a former journalist and correspondent.[55]

See also edit

References edit

- ^ a b Ojārs Greste (2010). "Austrālijas latvietis iesakņojies Āfrikā". Laikraksts Latvietis (in Latvian). Archived from the original on 3 January 2015.

- ^ https://researchers.uq.edu.au/researcher/20452

- ^ https://www.linkedin.com/in/peter-greste-7a530723/?originalSubdomain=au

- ^ Colvin, Mark (1 December 2014). "Peter Greste spends 49th birthday in Cairo prison". PM. ABC Radio. Archived from the original on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ^ https://researchers.uq.edu.au/researcher/20452

- ^ https://www.mq.edu.au/thisweek/2022/11/25/10-questions-with-peter-greste/

- ^ a b c "Canadian journalist asks Egyptian judge to free him: 'I ask for acquittal'". Toronto Star. 30 April 2014. Archived from the original on 13 July 2014. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ a b Patrick Kingsley (29 January 2014). "Egypt to charge al-Jazeera journalists with damaging country's reputation". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 December 2016.

- ^ "Secretary Kerry: Prison sentences for Al Jazeera reporters 'deeply disturbing set-back' for Egypt". Big News Network. Archived from the original on 24 June 2014. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ https://www.foreignminister.gov.au/minister/julie-bishop/transcript-eoe/press-conference-peter-greste

- ^ "Al Jazeera journalists Peter Greste, Mohammed Fahmy, Baher Mohamed sentenced to at least three years' jail". ABC News. 30 August 2015. Archived from the original on 4 December 2015. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ "Al Jazeera journalists Peter Greste, Mohammed Fahmy, Baher Mohamed sentenced to at least three years' jail". ABC News. 30 August 2015. Archived from the original on 4 December 2015. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ a b Fletcher, Clare (12 April 2015). "Peter Greste – the man behind the headlines". The Walkley Foundation. Archived from the original on 16 April 2015. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- ^ "Peter Greste calls on Tony Abbott to speak out for imprisoned journalists". The Guardian. 6 March 2014. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ Dalton, Trent (5 February 2015). "Peter Greste arrives back home". The Australian. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ^ https://researchers.uq.edu.au/researcher/20452

- ^ "Dispatches – Peter Greste". The Digital Journalist. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ^ "Peter Greste: Biography". Crossing Continents. BBC News. 31 March 2009. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ^ Listening Post. "Peter Greste – Al Jazeera Blogs". Blogs.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 25 December 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ^ Paul Farrell (5 February 2014). "Peter Greste and two al-Jazeera colleagues moved to same cell". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ "Egypt crisis: Al-Jazeera journalists arrested in Cairo". BBC News. 30 December 2013. Archived from the original on 8 July 2015.

- ^ Peter Greste (25 January 2014). "Peter Greste's letters from Egyptian jail". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 March 2017.

- ^ "UN urges Egypt to release foreign journalists, including Peter Greste". The Guardian. Australian Associated Press. 1 February 2014. Archived from the original on 2 December 2016.

- ^ "Egyptian court adjourns trial of Australian journalist Peter Greste". ABC News. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ "Peter Greste trial: Al Jazeera journalist found guilty". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Australia. 23 June 2014. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ "Egypt trial: Outcry over al-Jazeera trio's sentencing". BBC News. 23 June 2014. Archived from the original on 23 June 2014. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ "Egypt's president says will not interfere in judicial rulings". Reuters. Archived from the original on 25 June 2014. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- ^ "Egypt's press freedom on retrial". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 2 January 2015. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ "Egypt's press freedom on retrial". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 2 January 2015. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ "Peter Greste: Appeals court in Egypt orders retrial in case of Australian journalist". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 1 January 2015. Archived from the original on 1 January 2015. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

An Egyptian appeals court has ordered a retrial in the case of Australian journalist Peter Greste and two of his Al Jazeera colleagues.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, David D. (February 2015). "Egypt Deports Peter Greste, Journalist Jailed with 2 al Jazeera Colleagues". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 December 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ Greste released and deported Archived 1 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Al Jazeera journalists Peter Greste, Mohammed Fahmy, Baher Mohamed sentenced to at least three years' jail". ABC News. 30 August 2015. Archived from the original on 4 December 2015. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ "Peter Greste receives news of al-Jazeera journalist's pardon – video". The Guardian. 23 September 2015. Archived from the original on 26 December 2016.

- ^ https://rts.org.uk/tags/peter-greste

- ^ https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/commission-general/2015-human-rights-medal-and-awards-winners#:~:text=Peter%20Greste%20(WINNER)&text=Following%20his%20release%2C%20Peter%20used,media%20in%20properly%20functioning%20democracy.

- ^ "Freeing Peter by Andrew Greste". Archived from the original on 4 October 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ "2018 Walkley Book Award Shortlisted Finalists Announced". The Walkley Foundation. 7 November 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- ^ "The First Casualty by Peter Greste". Archived from the original on 4 October 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ "The First Casualty: a memoir from the front lines of Journalism". State Library Of Queensland One Search Catalogue. 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ James, Mathew R. (24 August 2017). "Cracking The Code". Medium. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ Greste, Peter (13 April 2017). "Facebook: Cracking the Code". Apple TV. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ "Facebook: Cracking the Code". mubi. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ "Peter Greste: Datenkrake Facebook. Das Milliarden-Geschäft mit der Privatsphäre (ZDFinfo)". de:Medienkorrespondenz (in German). Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ "Facebook: Cracking the Code - Trailer". Journeyman Pictures. 18 April 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ Monash and Me: Peter Greste on Australia's Great Commander. Artemis Media website, retrieved 22 November 2020

- ^ Monash and Me: Peter Greste on Australia's Great Commander. Artemis Media website, retrieved 22 November 2020

- ^ "Internationally acclaimed journalist appointed to UQ". UQ News. Archived from the original on 4 April 2018. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ Greste, Peter (12 April 2019). "Julian Assange is no journalist: don't confuse his arrest with press freedom". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- ^ Greste, Peter (12 April 2019). "Julian Assange is no journalist: don't confuse his arrest with press freedom". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- ^ https://www.mq.edu.au/thisweek/2022/11/25/10-questions-with-peter-greste/

- ^ "Peter Greste in Conversation". State Library of Queensland. 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ https://www.mq.edu.au/thisweek/2022/11/25/10-questions-with-peter-greste/

- ^ https://www.smh.com.au/national/we-just-hit-it-off-peter-greste-s-life-after-lock-up-20201203-p56kbu.html

- ^ https://www.mq.edu.au/thisweek/2022/11/25/10-questions-with-peter-greste/

External links edit

- Profile, Al Jazeera

- "Peter Greste". IMDb.

- Peter Greste on Twitter

- Inga Spriņģe : Pēteris Greste (ENG). 6 May 2015. Latvian Television.

- Peter Greste in Conversation State Library Of Queensland