The Protectorate of the Western Regions (simplified Chinese: 西域都护府; traditional Chinese: 西域都護府; pinyin: Xīyù Dūhù Fǔ; Wade–Giles: Hsi1-yü4 Tu1-hu4 Fu3) was an imperial administration (a protectorate) situated in the Western Regions administered by Han dynasty China and its successors on and off from 59 or 60 BCE until the end of the Sixteen Kingdoms period in 439 AD.[1] The "Western Regions" refers to areas west of Yumen Pass, especially the Tarim Basin in southern Xinjiang. These areas would later be termed Altishahr (southern Xinjiang, excluding Dzungaria) by Turkic-speaking peoples.[2] The term "western regions" was also used by the Chinese more generally to refer to Central Asia.

The protectorate was the first direct rule by a Chinese government of the area.[2][3] It consisted of various vassal states and Han garrisons placed under the authority of a Protector-General of the Western Regions, who was appointed by the Han court.

History edit

Background edit

During the Han–Xiongnu War, the Chinese empire established a military garrison at Wulei (west of Karasahr,[4] in present Luntai County[5]). The Chinese sought to control the Western Regions in order to keep the Xiongnu away from Inner China, and to control the valuable Silk Road trade that passed through the area. The local inhabitants of the Western Regions were diverse, and the area contained several groups who originated in Western Eurasia and/or spoke Indo-European languages. These groups included Tocharian-speaking city-states like Ārśi (Arshi; later Agni/Karasahr), Kuča (Kucha), Gumo (later Aksu), Turfan (Turpan), and Loulan (Krorän/Korla). Additionally, residents of the oasis city-states of Khotan and Kashgar spoke Saka, one of the Eastern Iranian languages.[6]

Prior to the establishment of the protectorate, there was a preceding post known as the "Colonel [for the Assistance of Imperial] Envoys" that was established a year after the War of the Heavenly Horses ended in 101 BC. After the war, Han posts were erected between Dunhuang and the Salt Marsh with several hundred farmer soldiers stationed at Luntai and Quli. The post was established to guard their farmland and to take care of grain storage for Han envoys traveling to other states.[7]

Establishment edit

The position of Protector-General was officially established in 59 or 60 BCE after the Southern Xiongnu ruler Bi, the Rizhu King of the Right, submitted to the Han dynasty. Rizhu was bestowed the title of Marquis of Allegiance to Imperial Authority while Zheng Ji, the envoy who received him, was commissioned to act Protector-General of both the Northern and Southern routes. Another account states that the post of Protector-General had already been established by 64 BC and Zheng Ji was sent out to meet Rizhu, who led over 10,000 Xiongnu to submit to Han authority. Under the Protector-General was a Deputy Colonel of the Western Regions. The Protector-General established a general headquarters at Wulei.[7]

It was the highest Han dynasty military position in the west during its existence. During the peak of the Protectorate's power in 51 BCE, the Wusun nation was brought under Han submission.[3] The post was abandoned after the usurpation of Wang Mang (Xin dynasty) from 8-22 CE. By then, at least 18 different people had served as protector-general, though only 10 of them have known names. In 45 CE, the eighteen states of the Western Regions requested the re-establishment of the Protectorate to restore peace to the region, but Emperor Guangwu of Han refused.[8]

During the second half of the first century CE, at the time of the Eastern Han dynasty, Chinese armies led by Ban Chao, Dou Gu, and Guo Xun brought the Western Regions back under Han control. The Protectorate was thus re-established.[9] In 74 CE, Emperor Ming of Han and his successor awarded the position of Protector-General (now with administrative obligations as well) to general Chen Mu. Chen Mu was killed by the rebellious troops of Yanqi and Qiuci.[8] In 83 CE, the office of Chief Official of the Western Regions was established and awarded to Ban Chao. The position of the Chief Official was beneath that of the Protector-General. Ban Chao would later be made Protector-General in 91 CE, after which he reconquered the Western Regions.[10] The seat of the Protectorate was for a time shifted to Taqian (or Tagan; near modern Kucha).[7] Ban Chao was succeeded by Ren Shang and Duan Xi.[8]

On 29 July 107, a series of Qiang uprisings in the areas of Hexi Corridor and Guanzhong. Duan Xi was killed and the post was abandoned. The Protectorate was later restored from 123-124 by the son of Ban Chao, Ban Yong. The Protectorate was again revived in 335 by Former Liang and headquartered in Gaochang until the demise of Northern Liang.[7]

In the southern Tarim Basin, coins from the period of the Protectorate's existence have been found with inscriptions in both Chinese and the Kharoshthi script, which was used for local Indo-European languages.[11]

In the 7th century, a successor administration, the Protectorate General to Pacify the West was established by the Tang Dynasty at Xizhou (Turpan) and was later moved to Kucha.[8]

Thirty-six city states edit

| City | Households | Population | Soldiers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beilu | 277 | 1,387 | 422 |

| Further Beilu | 462 | 1,137 | 350 |

| Danhuan | 27 | 194 | 45 |

| Guhu | 55 | 264 | 45 |

| Gumo | 3,500 | 24,500 | 4,500 |

| Hanmi | 3,340 | 20,040 | 3,540 |

| Jie | 99 | 500 | 115 |

| Jingjue | 480 | 3,360 | 500 |

| Eastern Jumi | 191 | 1,948 | 572 |

| Western Jumi | 332 | 1,926 | 738 |

| Jushi | 700 | 6,050 | 1,865 |

| Further Jushi | 595 | 4,774 | 1,890 |

| Loulan | 1,570 | 14,100 | 2,912 |

| Moshan | 450 | 5,000 | 1,000 |

| Pishan | 500 | 3,500 | 500 |

| Pulei | 325 | 2,032 | 799 |

| Further Pulei | 100 | 1,070 | 334 |

| Qiangruo | 450, | 1,750 | 500 |

| Qiemo | 230 | 1,610 | 320 |

| Qiuci | 6,970 | 81,317 | 21,076 |

| Qule | 310 | 2,170 | 300 |

| Quli | 240 | 1,610 | 300 |

| Shule | 1,510 | 18,647 | 2,000 |

| Suoju | 2,339 | 16,373 | 3,049 |

| Weili | 1,200 | 9,600 | 2,000 |

| Weitou | 300 | 2,300 | 800 |

| Weixu | 700 | 4,900 | 2,000 |

| Wensu | 2,200 | 8,400 | 1,500 |

| Wulei (Central Command) | 110 | 1,200 | 300 |

| Wutanzili | 41 | 231 | 57 |

| Xiaoyuan | 150 | 1,050 | 200 |

| Xiye | 350 | 4,000 | 1,000 |

| Yanqi (colony) | 4,000 | 32,100 | 6,000 |

| Yulishi | 190 | 1,445 | 331 |

| Yutian | 3,300 | 19,300 | 2,400 |

List of Protectors-General edit

Western Han and Xin edit

- Zheng Ji 60-48 BCE

- Han Xuan (韓宣) 48-45 BCE

- Unknown (3rd) 45-42 BCE

- Unknown (4th) 42-39 BCE

- Unknown (5th) 39-36 BCE

- Gan Yanshou (甘延壽) 36-33 BCE

- Duan Huizong (段會宗) 33-30, 21-18 BCE

- Lian Bao (廉褒) 30-27 BCE

- Unknown (9th) 27-24 BCE

- Han Li (韓立) 24-21 BCE

- Unknown (11th) 18-15 BCE

- Guo Shun (郭舜) 15-12 BCE

- Sun Jian (孫建) 12-9 BCE

- Unknown (14th) 9-6 BCE

- Unknown (15th) 6-3 BCE

- Unknown (16th) 3 BCE-1 CE

- Dan Qin (但欽) 1-13 CE

- Li Chong 13-23 CE

Eastern Han edit

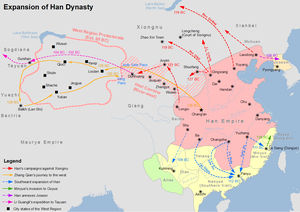

Maps edit

-

Asia in 1 AD. The Western Regions were at the centre of the map (south-west of the Xiongnu)

-

The Han dynasty (yellow) in 1 AD.

-

Modern Xinjiang, showingthe Tarim Basin.

-

1st century BC

See also edit

References edit

- ^ Tikhvinskiĭ, Sergeĭ Leonidovich; Perelomov, Leonard Sergeevich (1981). China and her neighbours, from ancient times to the Middle Ages: a collection of essays. Progress Publishers. p. 124. OCLC 8669104.

- ^ a b "Xiyu Duhu" Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Yu, Taishan (2003). A Comprehensive History of Western Regions (2nd ed.). Zhengzhou: Zhongzhou Guji Press. pp. 57–59. ISBN 7-5348-1266-6.

- ^ Thought and Law in Qin and Han China: Studies Dedicated to Anthony Hulsewâe on the Occasion of His Eightieth Birthday. Brill Archive. 1990. ISBN 978-90-04-09269-3.

- ^ The General Theory of Dunhuang Studies. Springer. 25 March 2022. ISBN 978-981-16-9073-0.

- ^ Tremblay, Xavier (2007). "The Spread of Buddhism in Serindia: Buddhism Among Iranians, Tocharians and Turks before the 13th Century". In Heirman, Ann; Bumbacker, Stephan Peter (eds.). The Spread of Buddhism. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill. p. 77. ISBN 978-90-04-15830-6.

- ^ a b c d Yu, Taishan (Oct 2006) [June 1995]. "A Study of the History of the Relationship Between the Western and Eastern Han, Wei, Jin, Northern and Southern Dynasties and the Western Regions" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers. Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. pp. 56, 68–71.

- ^ a b c d "The Western Territories 西域 (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ^ Cosmo 2009, p. 98.

- ^ Twitchett 2008, p. 421.

- ^ James A. Millward (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

Bibliography edit

- Cosmo, Nicola Di (2002), Ancient China and Its Enemies, Cambridge University Press

- Cosmo, Nicola di (2009), Military Culture in Imperial China, Harvard University Press

- Twitchett, Denis (2008), The Cambridge History of China: Volume 1, Cambridge University Press

External links edit

- Ma, Yong. "Xiyu Duhu" ("Protector General of the Western Regions"). Encyclopedia of China (Chinese History Edition), 1st ed.

- The Grand Game in Afghanistan

- Maps of Xinjiang