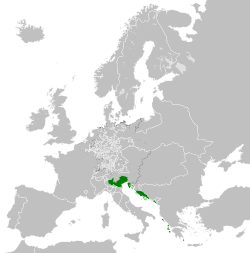

The Republic of Venice (Italian: Repubblica di Venezia; Venetian: Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic,[a] traditionally known as La Serenissima,[b] was a sovereign state and maritime republic in parts of the present-day Italian Republic that existed for 1,100 years from 697 until 1797.[2] Centered on the lagoon communities of the prosperous city of Venice, it incorporated numerous overseas possessions in modern Croatia, Slovenia, Montenegro, Greece, Albania and Cyprus.[4] The republic grew into a trading power during the Middle Ages and strengthened this position during the Renaissance. Most citizens spoke the Venetian language, although publishing in Italian became the norm during the Renaissance.

Most Serene Republic of Venice | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 697–1797 | |||||||||||||||

Coat of arms

(16–18th cent.) | |||||||||||||||

| Motto: Viva San Marco | |||||||||||||||

| Greater coat of arms (1706) | |||||||||||||||

The Republic of Venice in 1789, on the eve of the French Revolution | |||||||||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||||||||

| Official languages | |||||||||||||||

| Minority languages | |||||||||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism[3] | ||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Venetian | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Unitary mixed parliamentary classical republic under a mercantile oligarchy | ||||||||||||||

| Doge | |||||||||||||||

• 697–717 (first) | Paolo Lucio Anafestoa | ||||||||||||||

• 1789–1797 (last) | Ludovico Manin | ||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Great Council (since 1172) | ||||||||||||||

• Upper chamber | Senate | ||||||||||||||

• Lower chamber | Council of Ten (since 1310) | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | |||||||||||||||

• Establishment under first dogea as province of the Byzantine Empire | 697 | ||||||||||||||

• Pactum Lotharii (recognition of de facto independence, "province" dropped from name) | 840 | ||||||||||||||

• Golden Bull of Alexios I | 1082 | ||||||||||||||

| 1177 | |||||||||||||||

| 1204 | |||||||||||||||

| 1412 | |||||||||||||||

| 1571 | |||||||||||||||

| 1718 | |||||||||||||||

| 1797 | |||||||||||||||

| Currency | Venetian ducat Venetian lira | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

a. ^ Paolo Lucio Anafesto is traditionally the first Doge of Venice, but John Julius Norwich suggests that this may be a mistake for Paul, Exarch of Ravenna, and that the traditional second doge Marcello Tegalliano may have been the similarly named magister militum to Paul. Their existence as doges is uncorroborated by any source before the 11th century, but as Norwich suggests, is probably not entirely legendary. Traditionally, the establishment of the Republic is, thus, dated to 697 AD, not to the installation of the first contemporaneously recorded doge, Orso Ipato, in 726. | |||||||||||||||

In its early years, it prospered on the salt trade. In subsequent centuries, the city-state established a thalassocracy. It dominated trade on the Mediterranean Sea, including commerce between Europe and North Africa, as well as Asia. The Venetian navy was used in the Crusades, most notably in the Fourth Crusade. However, Venice perceived Rome as an enemy and maintained high levels of religious and ideological independence personified by the patriarch of Venice[5] and a highly developed independent publishing industry that served as a haven from Catholic censorship for many centuries. Venice achieved territorial conquests along the Adriatic Sea. It became home to an extremely wealthy merchant class, who patronised renowned art and architecture along the city's lagoons. Venetian merchants were influential financiers in Europe. The city was also the birthplace of great European explorers, such as Marco Polo, as well as Baroque composers such as Antonio Vivaldi and Benedetto Marcello and famous painters such as the Renaissance master Titian.

The republic was ruled by the doge, who was elected by members of the Great Council of Venice, the city-state's parliament, and ruled for life. The ruling class was an oligarchy of merchants and Venetian aristocrats. Venice and other Italian maritime republics played a key role in fostering capitalism. Venetian citizens generally supported the system of governance. The city-state enforced strict laws and employed ruthless tactics in its prisons.

The opening of new trade routes to the Americas and the East Indies via the Atlantic Ocean marked the beginning of Venice's decline as a powerful maritime republic. The city-state also suffered defeats at the hands of the navy of the Ottoman Empire. In 1797, the republic was plundered by retreating Austrian and then French forces, following an invasion by Napoleon Bonaparte. Subsequently, the Republic of Venice was divided into the Austrian Venetian Province, the Cisalpine Republic (a French client state), and the Ionian French departments of Greece. Venice, along with the whole of Veneto, became part of a unified Italy in the 19th century following the Kingdom of Italy's victory against Austria in the Third War of Italian Independence.

Etymology edit

During its long history, the Republic of Venice took on various names, all closely linked to the titles attributed to the doge. During the 8th century, when Venice still depended on the Byzantine Empire, the doge was called Dux Venetiarum Provinciae (English: "Doge of the Province of Venice"),[6] and then, starting from 840, Dux Veneticorum (English: "Doge of the Venetians"), following the signing of the Pactum Lotharii. This commercial agreement, stipulated between the Duchy of Venice (Latin: Ducatum Venetiae) and the Carolingian Empire, de facto ratified the independence of Venice from the Byzantine Empire.[7]

In the following century, references to Venice as a Byzantine dominion disappeared, and in a document from 976 there is a mention of the most glorious Domino Venetiarum (English: "Lord of Venice"), where the 'most glorious' appellative had already been used for the first time in the Pactum Lotharii and where the appellative "lord" refers to the fact that the doge was still considered like a king, even if elected by the popular assembly.[8] Gaining independence, Venice also began to expand on the coasts of the Adriatic Sea, and so starting from 1109, following the conquest of Dalmatia and the Croatian coast, the doge formally received the title of Venetiae Dalmatiae atque Chroatiae Dux (English: "Doge of Venice, Dalmatia and Croatia"), a name that continued to be used until the 18th century. Starting from the 15th century, the documents written in Latin were joined by those in the Venetian language and in parallel with the events in Italy, the Duchy of Venice also changed its name, becoming the Lordship of Venice, which as written in the peace treaty of 1453 with Sultan Mehmed II was fully named the lIlustrissima et Excellentissima deta Signoria de Venexia (English: "The Most Illustrious and Excellent Signoria of Venice").

During the 17th century, monarchical absolutism asserted itself in many countries of continental Europe, radically changing the European political landscape. This change made it possible to more markedly determine the differences between monarchies and republics: while the former were economies governed by strict laws and dominated by agriculture, the latter lived thanks to commercial affairs and free markets. Moreover, the monarchies, in addition to being led by a single ruling family, were more prone to war and religious uniformity. This increasingly noticeable difference between monarchy and republic began to be specified also in official documents, and it was hence that names such as the Republic of Genoa or the Republic of the Seven United Provinces were born. The Lordship of Venice also adapted to this new terminology, becoming the Most Serene Republic of Venice (Italian: Serenissima Repubblica di Venezia, Venetian: Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia), a name by which it is best known today. Similarly, the doge was also given the nickname of serenissimo or more simply that of His Serenity. From the 17th century the Republic of Venice took on other more or less official names such as the Venetian State or the Venetian Republic. The republic is often referred to as La Serenissima, in reference to its title as one of the "Most Serene Republics".

History edit

9th-10th century: The ducal age edit

The Duchy of Venice was born in the 9th century from the Byzantine territories of Maritime Venice. According to tradition, the first doge was elected in 697, but this figure is of dubious historicity and comparable to that of the exarch Paul, who, similarly to the doge, was assassinated in 727 following a revolt. Father Pietro Antonio of Venetia, in his history of the lagoon city published in 1688, writes: "The precise time in which that family arrived in the Adria is not found, but rather, what already an inhabitant of the islands, by the princes, who welcomed citizens, and supported with the advantage of significant riches, in the year 697 she contributed to the nomination of the first Prince Marco Contarini, one of the 22 Tribunes of the Islands, who made the election". In 726, Emperor Leo III attempted to extend iconoclasm to the Exarchate of Ravenna, causing numerous revolts throughout the territory. In reaction to the reform, the local populations appointed several dux to replace the Byzantine governors and in particular Venetia appointed Orso as its doge, who governed the lagoon for a decade. Following his death, the Byzantines entrusted the government of the province to the regime of the magistri militum, which lasted until 742 when the emperor granted the people the appointment of a dux. The Venetians elected by acclamation Theodato, son of Orso, who decided to move the capital of the duchy from Heraclia to Metamauco.[9]

The Lombard conquest of Ravenna in 751 and the subsequent conquest of the Lombard kingdom by Charlemagne's Franks in 774, with the creation of the Carolingian Empire in 800, considerably changed the geopolitical context of the lagoon, leading the Venetians to divide into two factions : a pro-Frankish party led by the city of Equilium and a pro-Byzantine party with a stronghold in Heraclia. After a long series of skirmishes in 805, Doge Obelerio decided to attack both cities simultaneously, deporting their population to the capital. Having taken control of the situation, the doge placed Venezia under Frankish protection, but a Byzantine naval blockade convinced him to renew his loyalty to the Eastern Emperor. With the intention of conquering Venezia in 810, the Frankish army commanded by Pepin invaded the lagoon, forcing the local population to retreat to Rivoalto, thus starting a siege which ended with the arrival of the Byzantine fleet and the retreat of the Franks. Following the failed Frankish conquest, Doge Obelerio was replaced by the pro-Byzantine nobleman Agnello Participazio who definitively moved the capital to Rivoalto in 812, thus decreeing the birth of the city of Venice.[10]

With his election, Agnello Partecipazio attempted to make the ducal office hereditary by associating an heir, the co-dux, with the throne. The system brought Agnello's two sons, Giustiniano and Giovanni, to the ducal position, who was deposed in 836 due to his inadequacy to counter the Narentine pirates in Dalmatia.[11] Following the deposition of Giovanni Partecipazio, Pietro Tradonico was elected who, with the promulgation of the Pactum Lotharii, a commercial treaty between Venice and the Carolingian Empire, began the long process of detachment of the province from the Byzantine Empire.[12] After Tradonico was killed following a conspiracy in 864, Orso I Participazio was elected and resumed the fight against piracy, managing to protect the Dogado from attacks by the Saracens and the Patriarchate of Aquileia. Orso managed to assign the dukedom to his eldest son Giovanni II Participazio who, after conquering Comacchio, a rival city of Venice in the salt trade, decided to abdicate in favor of his brother, at the time patriarch of Grado, who refused. Since there was no heir in 887 the people gathered in the Concio and elected Pietro I Candiano by acclamation.[13]

The Concio managed to elect six doges up to Pietro III Candiano who in 958 assigned the position of co-dux to his son Pietro who became doge the following year. Due to his land holdings, Pietro IV Candiano had a political vision close to that of the Holy Roman Empire and consequently attempted to establish feudalism in Venice as well, causing a revolt in 976 which led to the burning of the capital and the killing of the doge.[14] These events led the Venetian patriciate to gain a growing influence on the doge's policies and the conflicts that arose following the doge's assassination were resolved only in 991 with the election of Pietro II Orseolo.[15]

11th-12th century: Relations with the Byzantine Empire edit

Pietro II Orseolo gave a notable boost to Venetian commercial expansion by stipulating new commercial privileges with the Holy Roman Empire and the Byzantine Empire. In addition to diplomacy, the doge resumed the war against the Narentan pirates that began in the 9th century and in the year 1000 he managed to subjugate the coastal cities of Istria and Dalmatia.[16] The Great Schism of 1054 and the outbreak of the investiture struggle in 1073 marginally involved Venetian politics which instead focused its attention on the arrival of the Normans in southern Italy. The Norman occupation of Durrës and Corfu in 1081 pushed the Byzantine Empire to request the aid of the Venetian fleet which, with the promise of obtaining extensive commercial privileges and reimbursement of military expenses, decided to take part in the Byzantine-Norman wars.[17] The following year, Emperor Alexios I Komnenos granted Venice the chrysobol, a commercial privilege that allowed Venetian merchants substantial tax exemptions in numerous Byzantine ports and the establishment of a Venetian neighbourhood in Durrës and Constantinople. The war ended in 1085 when, following the death of the leader Robert Guiscard, the Norman army abandoned its positions to return to Puglia.[18]

Having taken office in 1118, Emperor John II Komnenos decided not to renew the chrysobol of 1082, arousing the reaction of Venice which declared war on the Byzantine Empire in 1122. The war ended in 1126 with the victory of Venice which forced the emperor to stipulate a new agreement characterized by even better conditions than the previous ones, thus making the Byzantine Empire totally dependent on Venetian trade and protection.[19] With the intention of weakening the growing Venetian power, the emperor provided substantial commercial support to the maritime republics of Ancona, Genoa and Pisa, making coexistence with Venice, which was now hegemonic on the Adriatic Sea, increasingly difficult, so much so that it was renamed the "Gulf of Venice". In 1171, following the emperor's decision to expel the Venetian merchants from Constantinople, a new war broke out which was resolved with the restoration of the status quo.[20] At the end of the 12th century, the commercial traffic of Venetian merchants extended throughout the East and they could count on immense and solid capital.[21]

As in the rest of Italy, starting from the 12th century, Venice also underwent the transformations that led to the age of the municipalities. In this century the doge's power began to decline: initially supported only by a few judges, in 1130 it was decided to place the Consilium Sapientium, which would later become the Great Council of Venice, alongside his power. In the same period, in addition to the expulsion of the clergy from public life, new assemblies such as the Council of Forty and the Minor Council were established and in his inauguration speech the Doge was forced to declare loyalty to the Republic with the promissione ducale;[22] thus the Commune of Venice, the set of all the assemblies aimed at regulating the power of the doge, began to take shape.[23]

13th-14th century: The Crusades and the rivalry with Genoa edit

In the 12th century, Venice decided not to participate in the Crusades due to its commercial interests in the East and instead concentrated on maintaining its possessions in Dalmatia which were repeatedly besieged by the Hungarians. The situation changed in 1202 when the Doge Enrico Dandolo decided to exploit the expedition of the Fourth Crusade to conclude the Zara War and the following year, after twenty years of conflict, Venice conquered the city and won the war, regaining control of Dalmatia.[24] The Venetian crusader fleet, however, did not stop in Dalmatia, but continued towards Constantinople to besiege it in 1204, thus putting an end to the Byzantine Empire and formally making Venice an independent state, severing the last ties with the former Byzantine ruler.[25] The empire was dismembered in the Crusader states and from the division Venice obtained numerous ports in the Morea and several islands in the Aegean Sea including Crete and Euboea, thus giving life to the Stato da Màr. In addition to the territorial conquests, the doge was awarded the title of Lord of a quarter and a half of the Eastern Roman Empire, thus obtaining the faculty of appointing the Latin Patriarchate of Constantinople and the possibility of sending a Venetian representative to the government of the Eastern Latin Empire.[26] With the end of the Fourth Crusade, Venice concentrated its efforts on the conquest of Crete, which intensely involved the Venetian army until 1237.[27]

Venice's control over the eastern trade routes became pressing and this caused an increase in conflicts with Genoa which in 1255 exploded into the War of Saint Sabas; on 24 June 1258 the two republics faced each other in the Battle of Acre which ended with an overwhelming Venetian victory. In 1261 the Empire of Nicaea with the help of the Republic of Genoa managed to dissolve the Eastern Latin Empire and re-establish the Byzantine Empire. The war between Genoa and Venice resumed and after a long series of battles the war ended in 1270 with the Peace of Cremona.[28] In 1281 Venice defeated the Republic of Ancona in battle and in 1293 a new war between Genoa, the Byzantine Empire and Venice broke out, won by the Genoese following the Battle of Curzola and ending in 1299.[29]

During the war, various administrative reforms were implemented in Venice, new assemblies were established to replace popular ones such as the Senate and in the Great Council power began to concentrate in the hands of about ten families. In order to avoid the birth of a lordship, the Doge decided to increase the number of members of the Maggior Consiglio while leaving the number of families unchanged and so the Serrata del Maggior Consiglio was implemented in 1297.[30] Following the provision, the power of some of the old houses decreased and in 1310, under the pretext of defeat in the Ferrara War, these families organized themselves in the Tiepolo conspiracy.[31] Once the coup d'état failed and the establishment of a lordship was averted, Doge Pietro Gradenigo established the Council of Ten, which was assigned the task of repressing any threat to the security of the state.[32]

In the Venetian hinterland, the war waged by Mastino II della Scala caused serious economic losses to Venetian trade, so in 1336 Venice gave birth to the anti-Scaliger league. The following year the coalition expanded further and Padua returned to the dominion of the Carraresi. In 1338, Venice conquered Treviso, the first nucleus of the Domini di Terraferma, and in 1339 it signed a peace treaty in which the Scaligeri promised not to interfere in Venetian trade and to recognize the sovereignty of Venice over the Trevisan March.[33]

In 1343 Venice took part in the Smyrniote crusades, but its participation was suspended due to the siege of Zadar by the Hungarians. The Genoese expansion to the east, which caused the Black Death, brought the rivalry between the two republics to resurface and in 1350 they faced each other in the War of the Straits. Following the defeat in the Battle of Sapienza, Doge Marino Faliero attempted to establish a city lordship, but the coup d'état was foiled by the Council of Ten which on 17 April 1355 condemned the Doge to death. The ensuing political instability convinced Louis I of Hungary to attack Dalmatia which was conquered in 1358 with the signing of the Treaty of Zadar. The weakness of the Republic pushed Crete and Trieste to revolt, but the rebellions were quelled, thus reaffirming Venetian dominion over the Stato da Màr. The skirmishes between the Venetians and the Genoese resumed and in 1378 the two republics faced each other in the War of Chioggia. Initially the Genoese managed to conquer Chioggia and vast areas of the Venetian Lagoon, but in the end it was the Venetians who prevailed; the war ended definitively on 8 August 1381 with the Treaty of Turin which sanctioned the exit of the Genoese from the competition for dominion over the Mediterranean.[34]

15th century: Territorial expansion edit

In 1403, the last major battle between the Genoese (now under French rule) and Venice was fought at Modon, and the final victory resulted in maritime hegemony and dominance of the eastern trade routes. The latter would soon be contested, however, by the inexorable rise of the Ottoman Empire. Hostilities began after Prince Mehmed I ended the civil war of the Ottoman Interregnum and established himself as sultan. The conflict escalated until Pietro Loredan won a crushing victory against the Turks off Gallipoli in 1416.

Venice expanded as well along the Dalmatian coast from Istria to Albania, which was acquired from King Ladislaus of Naples during the civil war in Hungary. Ladislaus was about to lose the conflict and had decided to escape to Naples, but before doing so he agreed to sell his now practically forfeit rights on the Dalmatian cities for the reduced sum of 100,000 ducats. Venice exploited the situation and quickly installed nobility to govern the area, for example, Count Filippo Stipanov in Zara. This move by the Venetians was a response to the threatening expansion of Gian Galeazzo Visconti, Duke of Milan. Control over the northeast main land routes was also a necessity for the safety of the trades. By 1410, Venice had a navy of 3,300 ships (manned by 36,000 men) and had taken over most of what is now the Veneto, including the cities of Verona (which swore its loyalty in the Devotion of Verona to Venice in 1405) and Padua.[35]

Slaves were plentiful in the Italian city-states as late as the 15th century. The Venetian slave trade was divided in to the Balkan slave trade and the Black Sea slave trade. Between 1414 and 1423, some 10,000 slaves, imported from Caffa (via the Black Sea slave trade), were sold in Venice.[36]

In the early 15th century, the republic began to expand onto the Terraferma. Thus, Vicenza, Belluno, and Feltre were acquired in 1404, and Padua, Verona, and Este in 1405. The situation in Dalmatia had been settled in 1408 by a truce with King Sigismund of Hungary, but the difficulties of Hungary finally granted to the republic the consolidation of its Adriatic dominions. The situation culminated in the Battle of Motta in late August 1412, when an invading army of Hungarians, Germans and Croats, led by Pippo Spano and Voivode Miklós Marczali[37] attacked the Venetian positions at Motta[38] and suffered a heavy defeat. At the expiration of the truce in 1420, Venice immediately invaded the Patriarchate of Aquileia and subjected Traù, Spalato, Durazzo, and other Dalmatian cities. In Lombardy, Venice acquired Brescia in 1426, Bergamo in 1428, and Cremona in 1499.

In 1454, a conspiracy for a rebellion against Venice was dismantled in Candia. The conspiracy was led by Sifis Vlastos as an opposition to the religious reforms for the unification of Churches agreed at the Council of Florence.[39] In 1481, Venice retook nearby Rovigo, which it had held previously from 1395 to 1438.

The Ottoman Empire started sea campaigns as early as 1423, when it waged a seven-year war with the Venetian Republic over maritime control of the Aegean, the Ionian, and the Adriatic Seas. The wars with Venice resumed after the Ottomans captured the Kingdom of Bosnia in 1463, and lasted until a favorable peace treaty was signed in 1479 just after the troublesome siege of Shkodra. In 1480, no longer hampered by the Venetian fleet, the Ottomans besieged Rhodes and briefly captured Otranto.

In February 1489, the island of Cyprus, previously a crusader state (the Kingdom of Cyprus), was added to Venice's holdings. By 1490, the population of Venice had risen to about 180,000 people.[40]

16th century: League of Cambrai, the loss of Cyprus, and Battle of Lepanto edit

War with the Ottomans resumed from 1499 to 1503. In 1499, Venice allied itself with Louis XII of France against Milan, gaining Cremona. In the same year, the Ottoman sultan moved to attack Lepanto by land and sent a large fleet to support his offensive by sea. Antonio Grimani, more a businessman and diplomat than a sailor, was defeated in the sea battle of Zonchio in 1499. The Turks once again sacked Friuli. Preferring peace to total war both against the Turks and by sea, Venice surrendered the bases of Lepanto, Durazzo, Modon, and Coron.

Venice's attention was diverted from its usual maritime position by the delicate situation in Romagna, then one of the richest lands in Italy, which was nominally part of the Papal States, but effectively divided into a series of small lordships which were difficult for Rome's troops to control. Eager to take some of Venice's lands, all neighbouring powers joined in the League of Cambrai in 1508, under the leadership of Pope Julius II. The pope wanted Romagna; Emperor Maximilian I: Friuli and Veneto; Spain: the Apulian ports; the king of France: Cremona; the king of Hungary: Dalmatia, and each one some of another's part. The offensive against the huge army enlisted by Venice was launched from France.

On 14 May 1509, Venice was crushingly defeated at the battle of Agnadello, in the Ghiara d'Adda, marking one of the most delicate points in Venetian history. French and imperial troops were occupying Veneto, but Venice managed to extricate itself through diplomatic efforts. The Apulian ports were ceded in order to come to terms with Spain, and Julius II soon recognized the danger brought by the eventual destruction of Venice (then the only Italian power able to face kingdoms like France or empires like the Ottomans).

The citizens of the mainland rose to the cry of "Marco, Marco", and Andrea Gritti recaptured Padua in July 1509, successfully defending it against the besieging imperial troops. Spain and the pope broke off their alliance with France, and Venice regained Brescia and Verona from France, also. After seven years of ruinous war, the Serenissima regained its mainland dominions west to the Adda River. Although the defeat had turned into a victory, the events of 1509 marked the end of the Venetian expansion.

In 1489, the first year of Venetian control of Cyprus, Turks attacked the Karpasia Peninsula, pillaging and taking captives to be sold into slavery. In 1539, the Turkish fleet attacked and destroyed Limassol. Fearing the ever-expanding Ottoman Empire, the Venetians had fortified Famagusta, Nicosia, and Kyrenia, but most other cities were easy prey. By 1563, the population of Venice had dropped to about 168,000 people.[40]

In the summer of 1570, the Turks struck again but this time with a full-scale invasion rather than a raid. About 60,000 troops, including cavalry and artillery, under the command of Mustafa Pasha landed unopposed near Limassol on 2 July 1570 and laid siege to Nicosia. In an orgy of victory on the day that the city fell – 9 September 1570 – 20,000 Nicosians were put to death, and every church, public building, and palace was looted.[41] Word of the massacre spread, and a few days later, Mustafa took Kyrenia without having to fire a shot. Famagusta, however, resisted and put up a defense that lasted from September 1570 until August 1571.

The fall of Famagusta marked the beginning of the Ottoman period in Cyprus. Two months later, the naval forces of the Holy League, composed mainly of Venetian, Spanish, and papal ships under the command of Don John of Austria, defeated the Turkish fleet at the battle of Lepanto.[42] Despite victory at sea over the Turks, Cyprus remained under Ottoman rule for the next three centuries. By 1575, the population of Venice was about 175,000 people, but partly as a result of the plague of 1575–76 the population dropped to 124,000 people by 1581.[40]

17th century edit

According to economic historian Jan De Vries, Venice's economic power in the Mediterranean had declined significantly by the start of the 17th century. De Vries attributes this decline to the loss of the spice trade, a declining uncompetitive textile industry, competition in book publishing from a rejuvenated Catholic Church, the adverse impact of the Thirty Years' War on Venice's key trade partners, and the increasing cost of cotton and silk imports to Venice.[43]

In 1606, a conflict between Venice and the Holy See began with the arrest of two clerics accused of petty crimes and with a law restricting the Church's right to enjoy and acquire landed property. Pope Paul V held that these provisions were contrary to canon law, and demanded that they be repealed. When this was refused, he placed Venice under an interdict which forbade clergymen from exercising almost all priestly duties. The republic paid no attention to the interdict or the act of excommunication and ordered its priests to carry out their ministry. It was supported in its decisions by the Servite friar Paolo Sarpi, a sharp polemical writer who was nominated to be the Signoria's adviser on theology and canon law in 1606. The interdict was lifted after a year, when France intervened and proposed a formula of compromise. Venice was satisfied with reaffirming the principle that no citizen was superior to the normal processes of law.[44]

Rivalry with Habsburg Spain and the Holy Roman Empire led to Venice's last significant wars in Italy and the northern Adriatic. Between 1615 and 1618 Venice fought Archduke Ferdinand of Austria in the Uskok war in the northern Adriatic and on the Republic's eastern border, while in Lombardy to the west, Venetian troops skirmished with the forces of Don Pedro de Toledo Osorio, Spanish governor of Milan, around Crema in 1617 and in the countryside of Romano di Lombardia in 1618. A fragile peace did not last, and in 1629 the Most Serene Republic returned to war with Spain and the Holy Roman Empire in the War of the Mantuan succession. During the brief war a Venetian army led by provveditore Zaccaria Sagredo and reinforced by French allies was disastrously routed by Imperial forces at the battle of Villabuona, and Venice's closest ally Mantua was sacked. Reversals elsewhere for the Holy Roman Empire and Spain ensured the republic suffered no territorial loss, and the duchy of Mantua was restored to Charles II Gonzaga, Duke of Nevers, who was the candidate backed by Venice and France.

The latter half of the 17th century also had prolonged wars with the Ottoman Empire; in the Cretan War (1645–1669), after a heroic siege that lasted 21 years, Venice lost its major overseas possession – the island of Crete (although it kept the control of the bases of Spinalonga and Suda) – while it made some advances in Dalmatia. In 1684, however, taking advantage of the Ottoman involvement against Austria in the Great Turkish War, the republic initiated the Morean War, which lasted until 1699 and in which it was able to conquer the Morea peninsula in southern Greece.

18th century: Decline edit

These gains did not last, however; in December 1714, the Turks began the last Turkish–Venetian War, when the Morea was "without any of those supplies which are so desirable even in countries where aid is near at hand which are not liable to attack from the sea".[45]

The Turks took the islands of Tinos and Aegina, crossed the isthmus, and took Corinth. Daniele Dolfin, commander of the Venetian fleet, thought it better to save the fleet than risk it for the Morea. When he eventually arrived on the scene, Nauplia, Modon, Corone, and Malvasia had fallen. Levkas in the Ionian islands, and the bases of Spinalonga and Suda on Crete, which still remained in Venetian hands, were abandoned. The Turks finally landed on Corfu, but its defenders managed to throw them back.

In the meantime, the Turks had suffered a grave defeat by the Austrians in the Battle of Petrovaradin on 5 August 1716. Venetian naval efforts in the Aegean Sea and the Dardanelles in 1717 and 1718, however, met with little success. With the Treaty of Passarowitz (21 July 1718), Austria made large territorial gains, but Venice lost the Morea, for which its small gains in Albania and Dalmatia were little compensation. This was the last war with the Ottoman Empire. By the year 1792, the once-great Venetian merchant fleet had declined to a mere 309 merchantmen.[46] Although Venice declined as a seaborne empire, it remained in possession of its continental domain north of the Po Valley, extending west almost to Milan. Many of its cities benefited greatly from the Pax Venetiae (Venetian peace) throughout the 18th century.

Fall edit

By 1796, the Republic of Venice could no longer defend itself since its war fleet numbered only four galleys and seven galiots.[47] In spring 1796, Piedmont (the Duchy of Savoy) fell to the invading French, and the Austrians were beaten from Montenotte to Lodi. The army under Bonaparte crossed the frontiers of neutral Venice in pursuit of the enemy. By the end of the year, the French troops were occupying the Venetian state up to the Adige River. Vicenza, Cadore and Friuli were held by the Austrians. With the campaigns of the next year, Napoleon aimed for the Austrian possessions across the Alps. In the preliminaries to the Peace of Leoben, the terms of which remained secret, the Austrians were to take the Venetian possessions in the Balkans as the price of peace (18 April 1797) while France acquired the Lombard part of the state.

After Napoleon's ultimatum, Ludovico Manin surrendered unconditionally on 12 May and abdicated, while the Major Council declared the end of the republic. According to Bonaparte's orders, the public powers passed to a provisional municipality under the French military governor. On 17 October, France and Austria signed the Treaty of Campo Formio, agreeing to share all the territory of the republic, with a new border just west of the Adige. Italian democrats, especially young poet Ugo Foscolo, viewed the treaty as a betrayal. The metropolitan part of the disbanded republic became an Austrian territory, under the name of Venetian Province (Provincia Veneta in Italian, Provinz Venedig in German).

Legacy edit

Though the economic vitality of the Venetian Republic had started to decline since the 16th century with the movement of international trade towards the Atlantic, its political regime still appeared in the 18th century as a model for the philosophers of the Enlightenment.

-

Relief of the Venetian Lion on the Landward Gate in Zadar, capital of Venetian Dalmatia

-

Relief of the Venetian Lion in Poreč

-

Relief of the Venetian Lion in Kotor

-

Relief of the Venetian Lion on the walls of Methoni

-

Relief of the Venetian Lion in Candia Heraklion

-

Relief of the Venetian Lion in Frangokastello, Crete

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was hired in July 1743 as secretary by Comte de Montaigu, who had been named ambassador of the French in Venice. This short experience, nevertheless, awakened the interest of Rousseau to the policy, which led him to design a large book of political philosophy.[48] After the Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men (1755), he published The Social Contract (1762).

Politics edit

In the early years of the republic, the Doge of Venice ruled Venice in an autocratic fashion, but later his powers were limited by the promissione ducale, a pledge he had to take when elected. As a result, powers were shared with the Maggior Consiglio or Great Council, composed of 480 members taken from patrician families, so that in the words of Marin Sanudo, "[The doge] could do nothing without the Great Council and the Great Council could do nothing without him".

Venice followed a mixed government model, combining monarchy in the doge, aristocracy in the Senate, republic of Rialto families in the Great Council, and a democracy in the Concio.[49] Machiavelli considered it ''excellent among modern republics'', unlike his native republic of Florence.[50][51]

In the 12th century, the aristocratic families of Rialto further diminished the doge's powers by establishing the Minor Council (1175), composed of the six ducal councillors, and the Council of Forty or Quarantia (1179) as a supreme tribunal. In 1223, these institutions were combined into the Signoria, which consisted of the doge, the Minor Council, and the three leaders of the Quarantia. The Signoria was the central body of government, representing the continuity of the republic as shown in the expression: "si è morto il Doge, no la Signoria" ("If the Doge is dead, the Signoria is not").

During the late 14th and early 15th centuries, the Signoria was supplemented by boards of savii ("wise men"): the six Savi del Consiglio, who formulated and executed government policy; the five Savi di Terraferma, responsible for military affairs and the defence of the Terraferma; and the five Savii agli Ordini, responsible for the navy, commerce, and the overseas territories. Together, the Signoria and the Savii formed the Full College (Pien Collegio), the de facto executive body of the republic. In 1229, the Consiglio dei Pregadi or Senate, was formed, being 60 members elected by the major council.[52] These developments left the doge with little personal power and put actual authority in the hands of the Great Council.

In 1310, a Council of Ten was established, becoming the central political body whose members operated in secret. Around 1600, its dominance over the major council was considered a threat, and efforts were made in the council and elsewhere to reduce its powers, with limited success.

In 1454, the Supreme Tribunal of the three state inquisitors was established to guard the security of the republic. By means of espionage, counterespionage, internal surveillance, and a network of informers, they ensured that Venice did not come under the rule of a single "signore", as many other Italian cities did at the time. One of the inquisitors—popularly known as Il Rosso ("the red one") because of his scarlet robe—was chosen from the doge's councillors, two—popularly known as I negri ("the black ones") because of their black robes—were chosen from the Council of Ten. The Supreme Tribunal gradually assumed some of the powers of the Council of Ten.[52]

In 1556, the provveditori ai beni inculti were also created for the improvement of agriculture by increasing the area under cultivation and encouraging private investment in agricultural improvement. The consistent rise in the price of grain during the 16th century encouraged the transfer of capital from trade to the land.

Armed forces and public security edit

During the Medieval period, the republic's military was composed of the following elements:

- Forza ordinaria (ordinary force), the oarsmen drafted from the citizens of the city of Venice; everyone from the age of 20–70 was obligated to serve in it. However, generally only a twelfth was active.

- Forza sussidiaria (subsidiary force), the military force drawn from Venice's overseas possessions.

- Forza straordinaria (extraordinary force), the mercenary part of the army; Venetian galleys tended to employ thirty mercenary crossbowmen. With the rise of scutage, it became the dominant element of the Venetian military.[53]

In the early modern period, the Republic's military strength was well out of proportion with its demographic weight. In the late 16th century, it ruled over a population of about 2 million people throughout its empire. In 1571, while preparing for war against the Ottomans, the republic had 37,000 soldiers and 140 galleys (manned by tens of thousands of sailors and oarsmen), excluding urban militias. The Venetian peacetime army strength of 9,000 was able to quadruple in the course of a few months by drawing upon professional hired soldiers and territorial militias simultaneously. These troops generally showed marked technical superiority over their primarily Turkish opponents, as demonstrated in battles such as the 18-month siege of Famagusta, in which the Venetians inflicted outsized casualties and only were defeated when they exhausted their gunpowder.

Like other states of the period, the republic's military strength peaked during wars, only to quickly go back to peacetime levels because of costs. The level of garrisons stabilized after 1577 at 9,000, with 7,000 infantry and the rest cavalry. In 1581 there were 146 galleys and 18 galleasses in the navy, requiring a third of the Republic's revenue.[54] During the Cretan War (1645-1669), the republic fought mostly alone against the undivided attention of the Ottoman Empire, and though it lost, managed to keep fighting after losing 62,000 troops in the attrition, while inflicting about 240,000 losses on the Ottoman army and sinking hundreds of Ottoman ships. The cost of the war was ruinous, but the republic was eventually able to cover it.[55] The Morean War further confirmed the republic's position as a military power well into the late 17th century.

Venetian military strength underwent a terminal decline in the 18th century. The combined effect of prolonged peace and the abandonment of military careers by patricians meant that Venetian military culture ossified. Its army in that period was poorly maintained. The troops, serving under non-martial officers, were not regularly drilled and worked various odd jobs to supplement their salaries. Its navy did not decline to as drastic a degree but still was greatly reduced from its relative power in the 16th and 17th centuries. In a normal 18th century year there were about 20 ships of the line (each of 64 or 70 cannons), 10 frigates, 20 galleys, and 100 small craft, which mostly participated in patrols and punitive expeditions against Barbary corsairs. When Napoleon invaded in 1796, the republic surrendered without a fight.[56]

Symbols edit

Since the retrieval of Mark the Evangelist's body from Alexandria in 828 and its arrival in Venice, the lagoon state established a special relationship with its patron. This bond, caused by the particular importance of the relic and above all by the bond existing between the Saint and the Churches of north-eastern Italy which traced their origins to his preaching, led to the patron saint being considered as the guardian of the State's sovereignty, becoming its symbol. The republic thus came to be called the Republic of Saint Mark and its lands were frequently known as Terre di San Marco.

The winged lion, symbol of Mark the Evangelist, appeared on the Republic's flags, coats of arms and seals, while the Doges themselves were depicted kneeling at the coronation, in the act of receiving the gonfalon from the Saint.

"Long live Saint Mark!" was the Republic of Venice's battle cry, used until its dissolution in 1797 following Napoleon's Italian campaign, and in the reborn republic governed by Daniele Manin and Niccolò Tommaseo. The cry "San Marco!" is used by the military personnel of the Lagunari Regiment "Serenissima" in every official activity or ceremony, since today's lagoon soldiers of the Italian army have inherited the traditions of the "Fanti da Mar" of the Serenissima.

The only equestrian order of the Republic was the Order of Saint Mark or the Doge.

Society edit

Starting from the 13th century, Venetian society clearly distinguished two social classes:

- Patricians

- The Venetian aristocracy was a relatively open social category documented in the Libro d'Oro: the first were the direct descendants of the first tribunes and their magistrates, to which were added the families who actively and above all economically participated in the War of Chioggia, the War of Candia and the Morean War. In 1774, all noble houses of the Mainland Dominions were also added to the Libro d'Oro. The Libro d'Oro was managed by the Avogadoria de Comùn and contained the list of all the births and weddings of the patriciate.[57] The aristocracy was not only a class of privileged people, but also of professional servants of the State. They were all educated, the richest attending the University of Padua while the impoverished nobility were educated for free at the Giudecca.[58] To prevent the concentration of power in a few hands, ensure a certain turnover and allow the greatest number of aristocrats to have employment, all these positions were short-lived, often lasting only one year and were often poorly paid. Nobles were not allowed to have relations with foreigners, leave the borders of the Republic, ask for pardons or distribute money; the nobility maintained itself even after judicial accusations and betrayal of the homeland.[59]

- Citizens

- Venetian citizenship was of three types:[60]

- Original citizens: Natives of Venice or from Venetian families up to the third degree enjoyed full citizenship, excluding Jews. The original citizens were also allowed to assume public offices, being able to become chancellors, secretaries, lawyers and notaries. Furthermore, citizens joined together in scholae, religious or professional confraternities that provided mutual aid to all members and allowed rules to be set for the various professions that took place in Venice.[61]

- Citizens de intra: New arrivals, based on merit, were granted full citizenship and the guarantee of the State within the borders and were allowed to carry out some jobs within the city.

- Citizens de extra: This was also a full citizenship granted on merit which conferred the privilege to sail and trade as a Venetian citizen.

Jews edit

The earliest evidence of Jewish presence in Venice dates back to 932;[62] in the 12th century the community had around a thousand members and was established in Mestre rather than Giudecca as was previously believed. Every day the Jews left Mestre and went to Venice, in particular to the San Marco and Rialto districts where they were allowed to work; here they trafficked goods and granted money loans, while some carried out the medical profession. Usury work was necessary for the functioning of the city's business activities and therefore, although they did not have citizenship and were not allowed to live there or buy a house, Jews were admitted to the capital with permits that were renewed every five or ten years. With a decree dated 22 May 1298, a limit was placed on the interest rate on loans, which was set between 10% and 12% and at the same time a tax of 5% was imposed on commercial traffic.[63]

In 1385, a group of Jewish moneylenders were allowed to live in the lagoon for the first time.[64] On 25 September 1386 they requested and obtained the purchase of part of the land of the Monastery of San Nicolò al Lido to bury their deceased, creating the Jewish cemetery of Venice, which is still functioning today. Towards the end of the 14th century, restrictions on Jews increased and they were only allowed to stay in the city for two weeks; furthermore they were forced to wear a yellow circle as a distinctive sign, which in the 16th century transformed into a red cloth.[65]

After the defeat of Agnadello by the League of Cambrai, many Jews from Vicenza and Conegliano took refuge in the lagoon, making coexistence with the Christians difficult. Following social tensions, the Venetian Ghetto was established on 29 March 1516 where the foundries had previously stood and in 1541 it was expanded to make room for the Levantine Jews.[66][67] The work of the Jews was placed under the supervision of the magistrates in Cattaver, and in addition to managing the ghetto's pawnshops they were allowed to trade in second-hand goods, making the ghetto an important commercial center. The ghetto was divided into communities based on their country of origin, each with its own synagogue.[68]

After the plague the ghetto was repopulated by some Eastern European Jews and in 1633 the ghetto was expanded,[69] but in the meantime Venice had lost its centrality and the Jewish community also began to shrink; taxes towards it increased and sectarian movements began to arise. The situation declined until in 1737 the community declared bankruptcy.[70]

Publishing edit

Printing and other graphic arts constituted a thriving economic sector of the Republic and the main means of disseminating Venetian knowledge and discoveries in the technical, humanistic and scientific fields. The birth of Venetian publishing dates back to the 15th century, in particular to 18 September 1469 when, through the efforts of the German Johann of Speyer, the Venetian government passed the first law to protect publishers by granting a printing privilege which gave the publisher the exclusive right to print certain works.[71] In addition to the German community, the French community, led by Nicolas Jenson, also owned most of the Venetian printing presses towards the end of the 15th century.[72]

Between 1495 and 1515 Aldus Manutius further developed Venetian publishing via three innovations which later spread throughout Europe: the octavo format, the italic character and the hooked comma. These inventions allowed him to become the largest Venetian publisher and consequently attracted the major humanists of the time, including Pietro Bembo and Erasmus.[73] After Manutius, many other Italian entrepreneurs such as the Florentine Lucantonio Giunti opened printing presses in Venice, which towards the end of the 16th century reached 200 businesses, each with higher book circulations than the average for European cities. The large quantity of printing houses scattered throughout the Venetian territory made the city of Venice a leader in the sector, so much so that in the last twenty years of the 15th century one book in ten in Europe was printed in Venice.[72] Book production in Venice was encouraged not only by the rules in favor of publishers, but also by the lack of censorship; in the 16th century works prohibited in the rest of Europe such as the Lustful Sonnets were printed in Venice.[74]

Religion edit

Catholicism edit

The Republic of Venice recognized Catholicism as the state religion and while remaining relatively tolerant compared to other confessions, there were many laws in favor of Catholic traditions given that according the 1770 census, approximately 86.5% of the population was Catholic.[75][76] The Catholic Church administered the territory of the Republic first with the Patriarchate of Grado which had the Diocese of Castello as its suffragen, which was then suppressed on 8 October 1451 by Pope Nicholas V in order to erect the Patriarchate of Venice which then also incorporated the dioceses of Jesolo, Torcello and Caorle. During the history of the Republic of Venice, the cathedral of the patriarchate was the Basilica of San Pietro di Castello which was changed to St Mark only in 1807, ten years after the fall of the Republic.[77] During the period of the Counter-Reformation, the Inquisition was also active in the Republic of Venice, which from 1542 to 1794 tried 3,620 defendants including Giordano Bruno, Pier Paolo Vergerio and Marco Antonio de Dominis. Crimes relating to faith, such as witchcraft, were regulated by a secular court as early as 1181 during the regency of Doge Orio Mastropiero. The tribunal, in addition to being made up of its judges appointed by the doge, also availed itself of the help of the bishops and the patriarch of Grado and the most widespread punishment for those convicted was that of being burned at the stake.[78] These magistrates continued to intervene as lay members even in the trials of the Inquisition, often coming into conflict with the Church and sometimes mitigating the harshness of the punishment.[79] Furthermore, the Inquisition only had power over Christians and not over members of other confessions such as Jews.[80] The government also regulated the construction of places of worship, limited bequests to the Church, favored by the presence of parish priests-notaries, and controlled priests who preached against the government, sometimes expelling them from the state.[81]

Other religions edit

In addition to the Catholic faith in the Republic of Venice, particularly in the Stato da Mar, the Orthodox church was also present; according to the 1770 census, the Orthodox Greeks constituted approximately 13.3% of the population.[76] The Greek Orthodox community was also present in the capital and in 1456 the Greeks obtained permission to build the church of San Biagio in Venice, the only church in the city where they could celebrate their rites. In 1514, due to overcrowding of San Biagio, the construction of the church of San Giorgio dei Greci was permitted.[82]

The remaining population belonged to other churches such as the Protestant and the Armenian Catholic churches and there were also Islamic merchants, who however did not reside permanently in Venice. The Armenians settled in Venice as early as the mid-13th century, although the construction of the first Armenian Catholic church, the church of Santa Croce degli Armeni, dates back only to 1682.[83] San Lazzaro degli Armeni also served as the Armenians' main cultural center.

The Protestant religion, which could be practiced freely, also spread in the Republic of Venice through commercial relations maintained with the Germans and the Swiss. In 1649 the Protestants obtained the possibility of burying their dead in the Church of San Bartolomeo and in 1657 they were allowed to celebrate masses with German shepherds in the Fondaco dei Tedeschi.[84]

In Venice there was also the Fondaco dei Turchi where the Ottoman merchants spent their time and in which there was a small mosque, the only place of prayer for the Muslim faithful who stayed in Venice.[85]

In 1770 there were only 5,026 Jews, equal to approximately 0.2% of the Republic of Venice's population,[76] but various laws were promulgated for this minority which limited their relationship with Catholics and their civil liberties. Following the expulsion of the Jews in almost all of Europe, the Jews of Venice were allowed to remain in the ghetto so as not to create disorder in the city and to be able to carry out their traditions and pray in the synagogues.[86] In Venice there were five synagogues belonging to the different Venetian Jewish communities, also called universities or nations, which held the liturgy here following different rites for each synagogue.[68]

Economy edit

Resources edit

Since the first settlements, fishing played a fundamental role in the livelihood of the lagoon communities. Fishing was one of the most widespread activities among the common people who also dedicated themselves to fish farming. After being caught, the fish was salted in order to improve preservation.[87] In addition to fishing, although to a lesser extent, hunting, fowling and pastoralism were widespread but were limited by the scarcity of pastures in the Dogado. Since pastures in the lagoon were limited, agriculture was instead widespread mainly with vegetable crops and some vineyards, the agricultural products of which were sold by fruit merchants.[88]

In addition to fishing, lagoon populations heavily relied on salt extraction for their livelihood. Owing to the salt trade, the first lagoon populations were able to purchase goods that the Venetian lagoon did not produce, primarily wheat. A direct competitor in the production of salt was Comacchio, which was destroyed in 932 and its population transferred to the Venetian lagoon. The areas of greatest production were the northern part of the lagoon and the district of Chioggia which over the centuries became the greatest salt producer in the Mediterranean, reaching its peak in the 13th century. Most of the salt produced in Chioggia was exported to Italy via the Po and the Adige. The salt pans were made up of a series of dams, basins and canals that allowed them to function correctly. Their extension was notable; the Chioggia salt pans occupied an area of approximately 30 km² which corresponded to ninety times the size of the city. The impetus for the foundations' construction was given by the Doge and the great ducal families who held the property. The estates of the nobles were rented to the families of the salt workers who independently maintained the salt pan and extracted the salt. The owners of the land had an exclusively economic relationship with the salt workers; consequently the nobles, owners of the land, could not consider themselves feudal lords as was the case in the rest of Europe in the cultivation of wheat. The salt workers also organized consortia which made noble imposition of the landowners even more difficult.[89] In the 14th century, during the height of commercial expansion, salt production in the lagoon had decreased. Regardless, Venice maintained a monopoly on this precious commodity by requiring merchants to transport a certain percentage of salt which was often purchased in Puglia, Sicily, Sardinia, the Balearic Islands, Cyprus and on the coast of Libya.[90]

Industry edit

Venetian glass, traded as early as the 9th century in the form of sheets, is still considered one of the leading products of the Venetian industry. Because of its quality, Venetian glass was used to make works of art exported all over the world.[91][92] Its production was located solely on the island of Murano in order to avoid the spread of fires within the capital.[93] Despite the glass production, the most successful activity was that of shipbuilding which took place within the state arsenal, active since the 12th century,[94] but also in the small Venetian shipyards of the city. Alongside the construction of ships, the production of naval cordage was developed by the filacànevi, who starting from the 13th century imported hemp from Russia via the Black Sea.[95] Among the activities already widespread in the 13th century were tanneries and wool spinning, which were exercised in Giudecca.[93]

Trade edit

From its early history, trade was the basis of the Republic of Venice's success and political rise: in 829, the Doge Giustiniano Participazio was involved not only in the management of his feudal assets but also in commercial affairs by sea.[91] The commercial enterprises of Venetian citizens increased in the 12th century, a period which saw the creation of the mude, caravans of merchant galleys which, escorted by armed ships, headed towards the eastern markets, starting with that of Constantinople.[21] Venice had a privileged relationship with the Byzantine Empire starting from 1082 when, with the issuing of the Golden Bull, Venetian merchants were allowed to exchange goods with the Byzantines without any tax and to establish an inhabited nucleus directly in the capital, a privilege which however ended violently in 1171 by the decree of Manuel I Komnenos.[96] Commercial traffic reached its peak in the 13th century, but continued to be fundamental in the political and social life of Venice until the end of the 16th century. This period saw the establishment of state-sanctioned mude, convoys of ships contracted to merchants which were used to reach faraway lands including India, China, England and Flanders. The Republic's trade was so extensive that in 1325 the existence of Venetian settlements was noted in northern European cities including Southampton and Bruges and in Asian cities such as Zaiton, Sudak, Azov, Trabzon, and Amman as well as other settlements on the shores of the Aral Sea.[97] Venetian trade suffered a sharp decline at the end of the 16th century when competition from the Portuguese, Spanish, English and Dutch became suffocating for Venetian merchants.[98]

The goods that the Venetians exchanged mostly by sea and which crowded the central Rialto market were: cotton, fabrics, iron, wood, alum, salt and spices exchanged as early as the 9th century; the testament of Bishop Orso Participazio, in which pepper is mentioned, dates back to 853.[91] In addition to pepper, Venice traded large quantities of cinnamon, cumin, coriander, cloves and many other spices which played a fundamental role in the preservation of meat, for the flavoring of wines and for medical treatments of which Venetian medicine made a large use. Spices also include sugar, produced in Cyprus and refined in Venice and all the perfumes and incenses widely used by Venetian patricians and during religious functions. In addition to spices, the East also supplied precious stones and silk, vice versa Venice brought European metals, wood, leather and fabrics to the East. Another good of which Venice held a monopoly was salt, which was shared wherever there was some, and given its usefulness the Republic obliged every merchant to transport a certain quantity. The salt monopoly, as well as being a commercial privilege, was also a political deterrent against foreign nations. Another commodity of fundamental importance was the cereals which were managed by the Wheat Chamber in order to combat possible famines. There was also a large import of oil used not only in seasoning but also for lighting.[97]

Coinage edit

The great expansion of Venetian trade began in the 12th century and the need for a stable currency became increasingly urgent. In 1202, during the dogate of Enrico Dandolo, the minting of the silver ducat (later called matapan) began, which quickly spread throughout the Mediterranean basin. The ducat corresponded to 26 denarii and weighed approximately two grams.[21][99] Like the other coins of the Republic of Venice, the ducat had the effigy of the reigning doge, who held the standard of Venice in front of Saint Mark.[100]

On 31 October 1284, Doge Giovanni Dandolo decided to mint a new currency, which would later be vital in the Venetian economy: the gold sequin, or ducat.[101] The sequin, made of excellent purity gold, weighed approximately 3.5 grams and its minting was interrupted only with the fall of the Republic.[102] Starting from the 16th century, minting took place in a special building overlooking the Marciano Pier, the Zecca of Venice, over whose activity the Council of Forty supervised.[100]

Culture edit

Theatre edit

Until the 17th century, theatrical works were performed in noble palaces or in public by the Compagnie della Calza who staged their works on mobile wooden theatres.[103] During the 17th century there was a great diffusion of the theater so much so that in 1637 Venice's first permanent theater, the Teatro San Cassiano, was inaugurated with a presentation of Andromeda by Benedetto Ferrari. Over the course of the century, thanks to the financing of the nobles, a dozen theaters were built in which tragedies and melodramas were mainly performed.[104] In Venice the reform of melodrama was initiated by Apostolo Zeno, who, inspired by French tragedy, made melodrama more sober and constructed his works so that they could be performed even without music.[105]

In the 17th century, although less widespread than melodramas, it represented commedia dell'arte. Based on the actors' improvisation and on canovaccio, it was characterized by a large number of stereotyped characters who generically represented the life of the various Venetian social classes.[106] In the 17th century, commedia dell'arte was completely reformed by Carlo Goldoni who introduced a new form of theater thanks to the elimination of masks and the introduction of a precise script. Conversely, Carlo Gozzi staged presentations of fairy tales, exalting and exasperating the tradition of commedia dell'arte.[107]

Fashion edit

Due to its commercial relationship with the East, the sumptuous clothing typical of the Byzantines soon spread in Venice, consisting mostly of embroidered or quilted blue tunics, the symbolic color of the Venetians. Among the common people, however, long canvas dresses decorated with colored stripes were widespread and the shoes were usually leather sandals. Over the cassock, men often wore large cloaks as well as belts and hats. The clothes of noblewomen were made of embroidered silk, very long and low-cut. They usually also wore trailing cloaks and furs from a large variety of animals, among which the ermine stood out. With the establishment of the guild in the 13th century, the art of tailors was also regulated and protected with the institution of dress tailors, ziponi tailors and sock tailors who dedicated themselves respectively to making clothes, fustian jackets and socks.[72]

With the beginning of the Renaissance following European fashion, the dresses of noblewomen became increasingly sumptuous, while men began to wear skirts combined with long two-tone stockings. Since the streets were not paved, they risked dirtying clothes, so very high clogs became widespread which were then removed once the home was reached. Between the 15th and 16th centuries the Baroque influence led to the excesses of noble clothing which in this era also began to be embellished with locally produced Burano lace.[108] To prevent the nobles and patricians from spending enormous amounts of money on clothing, in 1488 the Republic issued laws aimed at limiting the use of excessively expensive clothes, so much so that in 1514 pump supervisors were established who had the task of monitoring the amount of money spent on private parties, clothes and other luxury goods.[109]

In the 17th century the fashion for the wig and the use of face powder began and men's clothes progressively became bulkier. In the 18th century, the velada, a sort of large, richly decorated cloak, was introduced into men's clothing. Contrariwise, the vesta a cendà came into use among women's clothing, a modest dress which consisted of a long dress, usually black, and a white scarf. The poorer women, on the other hand, wore a round white dress that covered the head with a hood and was tied with a belt.[110]

Traditions edit

The Republic of Venice had numerous historical and folkloristic traditions of various kinds, some of which are still celebrated following its fall. In Venice, religious holidays were celebrated with extremely sumptuous processions directed towards St Mark's Basilica in which the Doge took part, preceded by the various government assemblies and the city's major schools. In addition to all the major Catholic holidays, the Feast of Saint Mark, which commemorates the city's patron saint, was also celebrated with equal pomp.[111] During the year, various masses were also held in memory of some fundamental events in the Republic's history, such as the failure of the Tiepolo conspiracy or that hatched by the Doge Marino Faliero and others such as the Festa delle Marie to celebrate the power of Venice.[112] One of the festivals of greatest political importance was the Festa della Sensa, celebrated on Ascension Day, which included a parade of boats led by the Bucentaur and the rite of the Marriage of the Sea which symbolized the maritime dominion of Venice.[113]

Among the profane festivals, one of the most important was the Carnival: celebrated for its entire duration, it included the major celebrations on Mardi Gras and Shrove Tuesday. In addition to dances and shows of various types, on the last Sunday of Carnival the bull hunt took place, an event similar to Spanish-style bullfighting. In addition to the Carnival, the Regatta was held, which like the other festivals included large celebrations and processions.[114]

See also edit

- Commune Veneciarum

- Francesco Apostoli (c. 1755–1816)

- History of the Byzantine Empire

- Italian Wars (1494–1559)

- List of historic states of Italy

- Ottoman wars in Europe

- Republic of San Marco (1848–49)

- Timeline of the Republic of Venice

- Venetian Albania

- Venetian Carnival

- Venetian Dalmatia

- Venetian Gothic architecture

- Venetian Ionian Islands

- Venetian nationalism

- Venetian navy

- Venetian nobility

- Venetian Renaissance architecture

- Venetian School (art)

- Venetian School (music)

- Venetian Slovenia

- Wars in Lombardy (1425–54)

Notes edit

- ^ Italian: Repubblica Veneta; Venetian: Repùblega Vèneta.

- ^ English: Most Serene Republic of Venice; Venetian: Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia.

References edit

- ^ "VENEZIA E LA LINGUA UFFICIALE DELLO STATO VENETO". VENEZIA E LA LINGUA UFFICIALE DELLO STATO VENETO. Archived from the original on 2 November 2022. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ a b Francesca Forzan (29 May 2021). "Venezia 1600: un dialetto e una lingua" (in Italian). Università di Padova. Archived from the original on 26 December 2022. Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- ^ Gordon, Scott (2009). Controlling the State: Constitutionalism from Ancient Athens to Today. Harvard University Press. p. 149. ISBN 9780674037830.

Venice was the most cosmopolitan city in Europe in the sixteenth century, but its many churches were almost entirely Christian and Catholic, and Catholicism was the official religion of the republic.

- ^ Arbel, Benjamin (1996). "Colonie d'oltremare". In Alberto Tenenti; Ugo Tucci (eds.). Storia di Venezia. Dalle origini alla caduta della Serenissima. Vol. Il: Rinascimento. Società ed economia (in Italian). Rome: Enciclopedia Italiana. pp. 947–985. OCLC 644711009. Archived from the original on 15 July 2020. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ "Translatio patriarchalis Ecclesiae Graden. ad civitatem Venetiarum, cum suppressione tituli eiusdem Ecclesiae Gradensis Archived 19 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine", in: Bullarum, diplomatum et privilegiorum sanctorum Romanorum pontificum Taurinensis editio, vol. 5 (Turin: Franco et Dalmazzo, 1860), pp. 107–109.

- ^ Romanin 1853, p. 348.

- ^ Romanin 1853, p. 356.

- ^ Romanin 1853, p. 376.

- ^ Zorzi 2001, pp. 24–26.

- ^ Zorzi 2001, pp. 27–31.

- ^ Zorzi 2001, p. 34.

- ^ Zorzi 2001, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Zorzi 2001, pp. 40–44.

- ^ Zorzi 2001, pp. 46–48.

- ^ Zorzi 2001, pp. 51–53.

- ^ Zorzi 2001, pp. 53–55.

- ^ Zorzi 2001, pp. 62–64.

- ^ Zorzi 2001, pp. 65–67.

- ^ Zorzi 2001, pp. 71–73.

- ^ Zorzi 2001, pp. 82–83.

- ^ a b c Zorzi 2001, pp. 91–93.

- ^ Zorzi 2001, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Zorzi 2001, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Zorzi 2001, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Zorzi 2001, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Zorzi 2001, pp. 114–115.

- ^ Zorzi 2001, p. 120.

- ^ Zorzi 2001, pp. 128–132.

- ^ Zorzi 2001, pp. 138–140.

- ^ Zorzi 2001, pp. 142–144.

- ^ Zorzi 2001, pp. 147–149.

- ^ Zorzi 2001, p. 153.

- ^ Zorzi 2001, pp. 172–173.

- ^ Zorzi 2001, pp. 199–205.

- ^ Norwich 1982, p. 269.

- ^ Witzenrath, Christoph (November 2015). Eurasian Slavery, Ransom and Abolition in World History, 1200–1860 (New ed.). Ashgate. p. 13. ISBN 978-1472410580. Archived from the original on 19 March 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ^ Engel, Pál (2001). The realm of St. Stephen: A History of Medieval Hungary, 895–1526. New York: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-8504-3977-6.

- ^ Mallett, M. E.; Hale, J. R. (1984). The Military Organisation of a Renaissance State, Venice c. 1400 to 1617. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-03247-4.

- ^ Manousakas, Manousos I. (1960). Ἡ ἐν Κρήτῃ συνωμοσία τοῦ Σήφη Βλαστοῦ (1453–1454) καὶ ἡ νέα συνωμοτικὴ κίνησις τοῦ 1460–1462 [The Conspiracy of Sēphēs Vlastos in Crete (1453–1454) and the New Conspiratorial Attempt of 1460–1462] (PhD thesis). Athens: National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. Archived from the original on 30 September 2020. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ a b c Norwich 1982, p. 494.

- ^ Turnbull, Stephen (2003). The Ottoman Empire 1326–1699. Routledge. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-415-96913-0.

- ^ Melisseides Ioannes A. (2010). "E epibiose:odoiporiko se chronus meta ten Alose tes Basileusas (1453–1605 peripou)", (in Greek), epim.Pulcheria Sabolea-Melisseide, Ekd.Vergina, Athens (WorldCat, Regesta Imperii, etc.), pp. 91–108, ISBN 9608280079

- ^ De Vries, Jan. "Europe in an age of crisis 1600–1750". Cambridge University Press. p. 26. Archived from the original on 3 September 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- ^ The Jesuits and Italian Universities, 1548–1773. Catholic University of America Press. 2017. p. 151. ISBN 978-0813229362. Archived from the original on 2 October 2022. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ Zorzi, Alvise (1983). Venice: The Golden Age, 697–1797. New York: Abbeville Press. p. 255. ISBN 0896594068. Archived from the original on 19 March 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ Norwich 1982, p. 591.

- ^ Norwich 1982, p. 615.

- ^ Trousson, Raymond (2012). Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Tallandier. p. 452. ISBN 9782847348743.

- ^ The Political Ideas of St. Thomas Aquinas, Dino Bigongiari ed., Hafner Publishing Company, NY, 1953. p. xxx in footnote.

- ^ Niccolò Machiavelli, The Prince, trans. & ed. by Robert M. Adams, New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1992. Machiavelli Balanced Government Archived 4 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Niccolò Machiavelli, Discourses on Livy, trans. by Harvey C. Mansfield and Nathan Tarcov, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1996.

- ^ a b Catholic Encyclopedia, "Venice Archived 23 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine", p. 602.

- ^ Heath, Ian (2016). Armies of Feudal Europe 1066–1300. Lulu.com. pp. 62–65. ISBN 9781326256524. Archived from the original on 25 October 2020. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ Hanlon 1997, pp. 19–20, 25, 87.

- ^ Paoletti, Ciro (2008). A Military History of Italy. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 33. ISBN 9780275985059.

- ^ Hanlon 1997, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Mutinelli 1851, pp. 223–224.

- ^ Mutinelli 1851, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Mutinelli 1851, pp. 278–279.

- ^ Mutinelli 1851, pp. 105–106.

- ^ Mutinelli 1851, pp. 364–365.

- ^ "Storia - Le origini: Gli ebrei a Venezia". JVenice (in Italian). Jewish Community of Venice. Archived from the original on 29 November 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ^ Cappelletti 1853, pp. 120–123.

- ^ "Storia - La prima condotta". JVenice (in Italian). Jewish Community of Venice. Archived from the original on 28 November 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ^ Cappelletti 1853, pp. 123–132.

- ^ "Storia - La nascita del Ghetto - I Tedeschi". JVenice. Jewish Community of Venice. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ^ "Storia - Levantini e Ponentini". JVenice (in Italian). Jewish Community of Venice. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ^ a b "Storia - La Natione italiana". JVenice (in Italian). Jewish Community of Venice. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ^ "Storia - La peste e la ripresa del Ghetto". JVenice (in Italian). Jewish Community of Venice. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ^ "Storia - Dalla crisi economica al messianesimo di Sabbatai Zevi". JVenice (in Italian). Jewish Community of Venice. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ^ "Privilegio di stampa". Treccani (in Italian). Istituto della Enciclopedia Italianafondata da Giovanni Treccani S.p.A. Retrieved 3 April 2024.

- ^ a b c Ciriacono 1996.

- ^ "Aldo Manuzio - Note biografiche". Archived from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- ^ Magno 2012, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Cecchetti 1874, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Castiglioni 1862, p. 301.

- ^ "Storia del Patriarcato - Patriarcato di Venezia" (in Italian). Patriarcato de Venezia. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ Cecchetti 1874, pp. 14–16.

- ^ Cecchetti 1874, p. 279.

- ^ Cecchetti 1874, p. 34.

- ^ Cecchetti 1874, pp. 85–90.

- ^ Cecchetti 1874, pp. 459–461.

- ^ Cecchetti 1874, pp. 489–493.

- ^ Cecchetti 1874, pp. 474–475.

- ^ Sagredo & Berchet 1860, pp. 68.

- ^ Cecchetti 1874, pp. 478–487.

- ^ Zorzi 2001, p. 60.

- ^ Zorzi 2001, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Hocquet, Jean-Claude (1992). "Eta Ducale - Le risorse: le saline". Treccani. Archived from the original on 19 September 2018. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ Zorzi 2001, pp. 160–161.

- ^ a b c Zorzi 2001, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Zorzi 2001, p. 282.

- ^ a b Zorzi 2001, p. 121.

- ^ "Storia dell'Arsenale". Città di Venezia. 19 March 2020. Archived from the original on 14 June 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ^ Zorzi 2001, p. 122.

- ^ Zorzi 2001, p. 66.

- ^ a b Zorzi 2001, pp. 158–163.

- ^ Zorzi 2001, pp. 366–367.

- ^ "Grozzo Enrico Dandolo". LaMoneta. Archived from the original on 17 February 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ a b "Venezia". LaMoneta. Archived from the original on 17 February 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ Zorzi 2001, p. 164.

- ^ "Ducato". LaMoneta. Archived from the original on 17 February 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ Mutinelli 1851, pp. 381–382.

- ^ Romanin 1858, p. 548.

- ^ Romanin 1860, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Romanin 1858, p. 551.

- ^ Romanin 1860, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Mutinelli 1851, p. 71.

- ^ Mutinelli 1851, p. 322.

- ^ Mutinelli 1851, p. 3.

- ^ Romanin 1860, pp. 25–29.

- ^ Romanin 1860, pp. 30–32.

- ^ Romanin 1860, pp. 36–40.

- ^ Romanin 1860, pp. 44–45.

Bibliography edit

Primary sources edit

- Contarini, Gasparo (1599). The Commonwealth and Government of Venice. Lewes Lewkenor, translator. London: "Imprinted by I. Windet for E. Mattes". The most important contemporary account of Venice's governance during the time of its blossoming; numerous reprint editions; online facsimile.

Secondary sources edit

- Benvenuti, Gino (1989). Le repubbliche marinare. Rome: Newton Compton.

- Brown, Patricia Fortini (2004). Private Lives in Renaissance Venice: art, architecture, and the family.

- Cappelletti, Giuseppe (1853). Stabilimento nazionale di G. Antonelli editore (ed.). Storia della Repubblica di Venezia dal suo principio sino al suo fine. Vol. 10. Venezia.