This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (July 2020) |

The Southwest Script or Southwestern Script, also known as Tartessian, South Lusitanian and Conii script is a Paleohispanic script used to write an unknown language usually identified as Tartessian. Southwest inscriptions have been found mainly in the southwestern quadrant of the Iberian Peninsula, mostly in the south of Portugal (Algarve and southern Alentejo), but also in Spain (in southern Extremadura and western Andalusia).

Name of the script edit

The name of this script is controversial.[1] The more neutral name is southwestern, because it refers only to the geographic location.[1] Some ethnolinguistic names given to this script include:

- Tartessian, considering it to be the script of the language spoken in Tartessos.[1] This is considered unlikely by some as only four of the hundred inscriptions currently known were found in Tartessos' area of influence.[1]

- South Lusitanian, because almost all of the southwest inscriptions have been found in the south of Portugal and that area was included in the Roman province Lusitania. However, the name may wrongly suggest a relation with the Lusitanian language.

- Conii script, as Greek and Roman sources locate the Pre-Roman Conii or Cynetes in the area where most stele were found.

- Bastulo-Turdetanian.

Deciphering strategies edit

Unlike the northeastern Iberian script, the deciphering of the southwestern script is not yet closed (as is the case with the southeastern Iberian script).[1] The two main approaches to deciphering the phonetic value of the letters have consisted of:[1]

- Comparative approach: searching for similar letters in the southwestern script and the Phoenician abjad and other paleoiberian scripts (namely NE and SE scripts). Then, their phonetic value is compared. If the letter appears to be of Phoenician origin and to have a similar phonetic value in both Phoenician and other paleoiberian scripts, then that phonetic value is assumed to be the same in the southwestern script.

- Internal analysis: searching for aspects of the language itself, such as frequency and relationship to other letters.

If the two approaches coincide, then the letter is considered to be deciphered and if not, then it is considered to be hypothetical.[1] As of 2014, 20 letters are considered to be consensual (all 5 vowels, 10 stops and 5 non-stops), while all others (10+) are still hypothetical.[1] The three main hypotheses are Correa (2009), de Hoz (2010), and Ramos (2002).[1]

Because the phonetic deciphering stage is not finished, it is difficult to establish what language the script is used to represent.[1] Some have suggested a Celtic origin, but this idea is not consensual.[1][2] If this hypothesis is correct, though, the Southwest script language would be the first Celtic language to be written.[2] The other main hypotheses are that the language is Iberian (or at any point non-Indo-European) and that the language has Celt influence, but an Iberian origin.[2]

Writing system edit

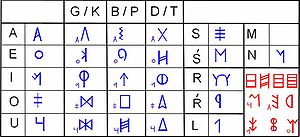

Excepting the Greco-Iberian alphabet, and to a lesser extent this script, paleoiberian scripts shared a distinctive typology: they behaved as a syllabary for the stop consonants and as an alphabet for the remaining consonants and vowels. This unique writing system has been called a semi-syllabary.

There is no agreement about how the paleohispanic semi-syllabaries originated; it is typically agreed that their origin is linked to the Phoenician abjad,[1] but some believe the Greek alphabet had influence. In the southwest script, though the letter used to write a stop consonant was determined by the following vowel, as in a full semi-syllabary, the following vowel was also written, as in an alphabet. A similar convention is found in Etruscan for /k/, which was written KA CE CI QU depending on the following vowel. Some scholars treat Tartessian as a redundant semi-syllabary, others treat it as a redundant alphabet.

The southwest script is very similar to the southeastern Iberian script, both considering the shape of the signs and their value. The main difference is that the southeast Iberian script doesn't show the vocalic redundancy of the syllabic signs.[1] This characteristic was discovered by Ulrich Schmoll and allows the classification of a great part of the southwestern signs into vowels, consonants and syllabic signs.

Inscriptions edit

This script is almost exclusively found in almost a hundred large stones (steles), of which 10 were lost as of 2014.[1] Most were found in modern-day Portugal, particularly from Baixo Alentejo, but some have been found in Spain.[1] Sixteen of these steles can be seen in the Southwest Script Museum (Museu da Escrita do Sudoeste, in Portuguese), in Almodôvar (Portugal), where a stele with a total of 86 characters (the longest inscription found so far) discovered in 2008 is also on display.[3][4][5]

The inscriptions probably had a funerary purpose, even though the lack of well-recorded archeological contexts of the findings makes it hard to be certain.[1] This same factor does not permit fixing a precise chronology, but it is placed within the Iron Age, in a range around 8th to 6th Century BCE.[1] It is usual considering that the southwestern script is the most ancient paleohispanic script. The direction of the writing is usually right to left, but it can also be a boustrophedon or spiral.

See also edit

Notes edit

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Valério, Miguel (2014). "The Interpretative Limits of the Southwestern Script". The Journal of Indo-European Studies. 42 (3/4): 439–467. ProQuest 1628229756.

- ^ a b c Koch, John T. (2014). "On the Debate over the Classification of the Language of the South-Western (SW) Inscriptions, also known as Tartessian". The Journal of Indo-European Studies. 42 (3/4): 335–427. ProQuest 1628230270.

- ^ Dias, Carlos (15 September 2008). "Descoberta perto de Almodôvar a mais extensa inscrição em escrita do sudoeste" [Discovery near Almodôvar the most extensive inscription in script in the southwest]. Público (in Portuguese).

- ^ "Experts trying to decipher ancient language". Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- ^ "Experts aim to decipher ancient script 2,500-year-old writing found on stone tablets in Portugal". NBC News. March 2009. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

References edit

- Correa, José Antonio (1996): «La epigrafía del sudoeste: estado de la cuestión», La Hispania prerromana, pp. 65–75.

- Correia, Virgílio-Hipólito (1996): «A escrita pré-romana do Sudoeste peninsular», De Ulisses a Viriato: o primeiro milenio a.c., pp. 88–94.

- Ferrer i Jané, Joan (2016): «Una aproximació quantitativa a l’anàlisi de l’escriptura del sud-oest», Palaeohispanica 16, pp. 39–79.

- Guerra, Amilcar (2002): «Novos monumentos epigrafados com escrita do Sudoeste da vertente setentrional da Serra do Caldeirao» Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine, Revista portuguesa de arqueologia 5–2, pp. 219–231.

- Hoz, Javier de (1985): «El origen de la escritura del S.O.», Actas del III coloquio sobre lenguas y culturas paleohispánicas, pp. 423–464.

- Koch J.T. Tartessian. Celtic in the South-West at the Dawn of History. Aberystwyth, 2009.

- Koch J. T., B. Cunliffe (eds.). Celtic from the West 2. Rethinking the Bronze Age and the Arrival of Indo-European in Atlantic Europe. Oxford / Oakville: Oxbow books, 2013.

- Rodríguez Ramos, Jesús (2000): «La lectura de las inscripciones sudlusitano-tartesias»[permanent dead link], Faventia 22/1, pp. 21–48.

- Schmoll, Ulrich (1961) : Die sudlusitanischen Inschriften, Wiesbaden.

- Untermann, Jürgen (1997): Monumenta Linguarum Hispanicarum. IV Die tartessischen, keltiberischen und lusitanischen Inschriften, Wiesbaden.

- Valério, Miguel (2008): Origin and development of the Paleohispanic scripts: The Orthography and Phonology of the Southwestern Alphabet[1]