articulated behind to the thoracic vertebrae, and as they are sym- metrical on the two sides of the body, the ribs in any given animal are always twice as numerous as the thoracic vertebrae in that animal. They form a series of osseocartilaginous arches, which

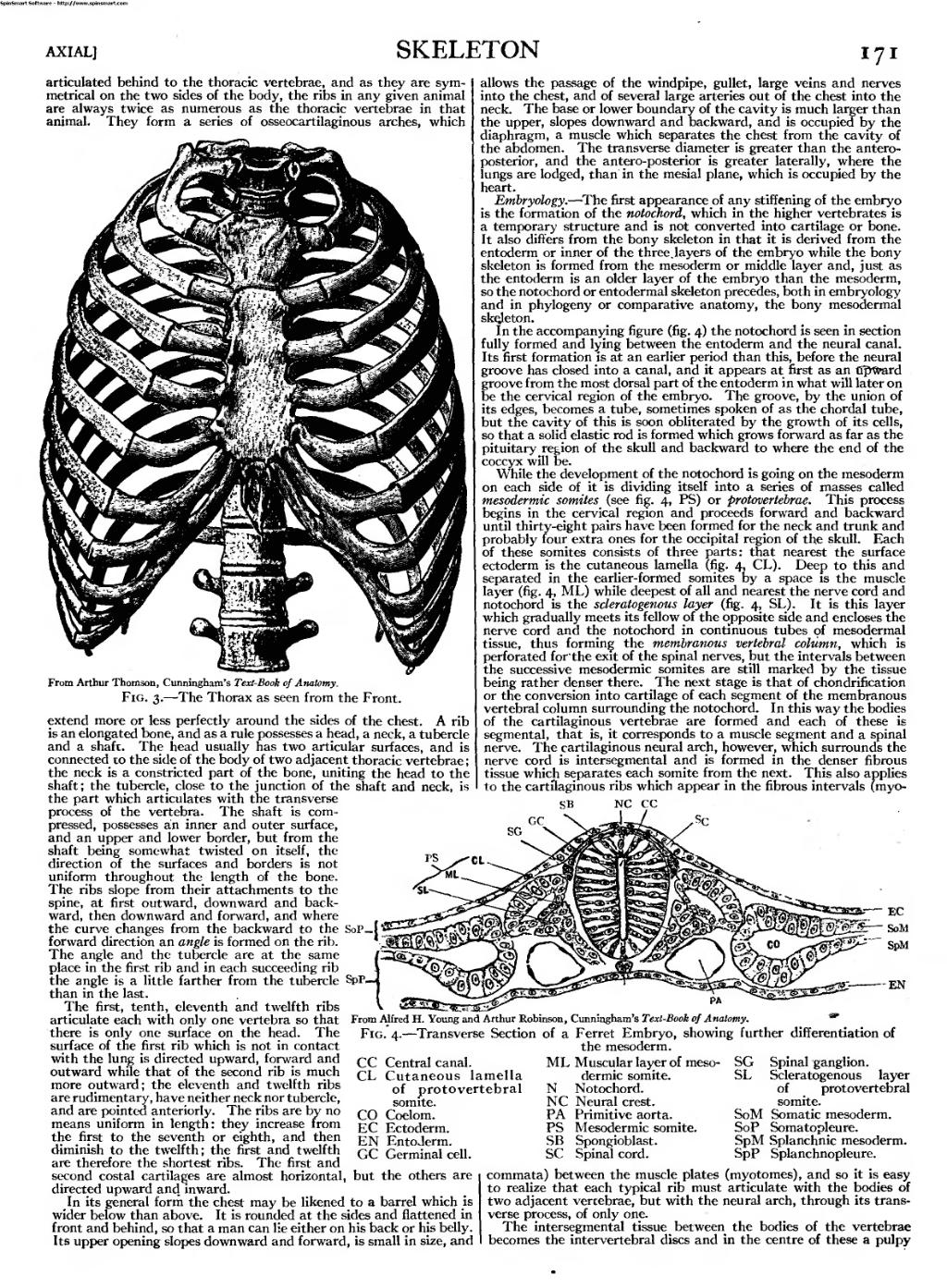

From Arthur Thomson, Cunningham's Text-Book of Anatomy.

Fig. 3. — The Thorax as seen from the Front.

extend more or less perfectly around the sides of the chest. A rib is an elongated bone, and as a rule possesses a head, a neck, a tubercle and a shaft. The head usually has two articular surfaces, and is connected to the side of the body of two adjacent thoracic vertebrae ; the neck is a constricted part of the bone, uniting the head to the shaft; the tubercle, close to the junction of the shaft and neck, is the part which articulates with the transverse process of the vertebra. The shaft is com- pressed, possesses an inner and outer surface, and an upper and lower border, but from the shaft being somewhat twisted on itself, the direction of the surfaces and borders is not uniform throughout the length of the bone. The ribs slope from their attachments to the spine, at first outward, downward and back- ward, then downward and forward, and where the curve changes from the backward to the SoP forward direction an angle is formed on the rib. The angle and the tubercle are at the same place in the first rib and in each succeeding rib the angle is a little farther from the tubercle SpP_ than in the last.

The first, tenth, eleventh and twelfth ribs articulate each with only one vertebra so that there is only one surface on the head. The

surface of the first rib which is not in contact

with the lung is directed upward, forward and

outward while that of the second rib is much

more outward; the eleventh and twelfth ribs

are rudimentary, have neither neck nor tubercle,

and are pointed anteriorly. The ribs are by no

means uniform in length: they increase from

the first to the seventh or eighth, and then

diminish to the twelfth; the first and twelfth

are therefore the shortest ribs. The first and

second costal cartilages are almost horizontal, but the others are

directed upward and. inward.

In its general form the chest may be likened to a barrel which is

wider below than above. It is rounded at the sides and flattened in

front and behind, so that a man can lie either on his back or his belly.

Its upper opening slopes downward and forward, is small in size, and

allows the passage of the windpipe, gullet, large veins and nerves into the chest, and of several large arteries out of the chest into the neck. The base or lower boundary of the cavity is much larger than the upper, slopes downward and backward, and is occupied by the diaphragm, a muscle which separates the chest from the cavity of the abdomen. The transverse diameter is greater than the antero- posterior, and the antero-posterior is greater laterally, where the lungs are lodged, than in the mesial plane, which is occupied by the heart.

Embryology. — The first appearance of any stiffening of the embryo is the formation of the notochord, which in the higher vertebrates is a temporary structure and is not converted into cartilage or bone. It also differs from the bony skeleton in that it is derived from the entoderm or inner of the three. layers of the embryo while the bony skeleton is formed from the mesoderm or middle layer and, just as the entoderm is an older layer of the embryo than the mesoderm, so the notochord or entodermal skeleton precedes, both in embryology and in phylogeny or comparative anatomy, the bony mesodermal skejeton.

In the accompanying figure (fig. 4) the notochord is seen in section fully formed and lying between the entoderm and the neural canal. Its first formation is at an earlier period than this, before the neural groove has closed into a canal, and it appears at first as an tfpWard groove from the most dorsal part of the entoderm in what will later on be the cervical region of the embryo. The groove, by the union of its edges, becomes a tube, sometimes spoken of as the chordal tube, but the cavity of this is soon obliterated by the growth of its cells, so that a solid elastic rod is formed which grows forward as far as the pituitary region of the skull and backward to where the end of the coccyx will be.

While the development of the notochord is going on the mesoderm on each side of it is dividing itself into a series of masses called mesodermic somites (see fig. 4, PS) or protovertebrae. This process begins in the cervical region and proceeds forward and backward until thirty-eight pairs have been formed for the neck and trunk and probably four extra ones for the occipital region of the skull. Each of these somites consists of three parts: that nearest the surface ectoderm is the cutaneous lamella (fig. 4, CL). Deep to this and separated in the earlier-formed somites by a space is the muscle layer (fig. 4, ML) while deepest of all and nearest the nerve cord and notochord is the scleratogenous layer (fig. 4, SL). It is this layer which gradually meets its fellow of the opposite side and encloses the nerve cord and the notochord in continuous tubes of mesodermal tissue, thus forming the membranous vertebral column, which is perforated for'the exit of the spinal nerves, but the intervals between the successive mesodermic somites are still marked by the tissue being rather denser there. The next stage is that of chondrification or the conversion into cartilage of each segment of the membranous vertebral column surrounding the notochord. In this way the bodies of the cartilaginous vertebrae are formed and each of these is segmental, that is, it corresponds to a muscle segment and a spinal nerve. The cartilaginous neural arch, however, which surrounds the nerve cord is intersegmental and is formed in the denser fibrous tissue which separates each somite from the next. This also applies to the cartilaginous ribs which appear in the fibrous intervals (myo-

SB

CC

CL

CO EC

EN

Central canal. Cutaneous lamella

of protovertebral

somite. Coelom. Ectoderm. Entoderm.

SG SL

An image should appear at this position in the text. To use the entire page scan as a placeholder, edit this page and replace "{{missing image}}" with "{{raw image|EB1911 - Volume 25.djvu/187}}". Otherwise, if you are able to provide the image then please do so. For guidance, see Wikisource:Image guidelines and Help:Adding images. |

From Alfred H. Young and Arthur Robinson, Cunningham's Text-Book of Anatomy. m

Fig. 4. — Transverse Section of a Ferret Embryo, showing further differentiation of

the mesoderm.

ML Muscular layer of meso- dermic somite.

N Notochord.

NC Neural crest.

PA Primitive aorta.

PS Mesodermic somite.

SB Spongioblast.

SC Spinal cord.

GC Germinal cell.

Spinal ganglion. Scleratogenous layer of protovertebral somite. Somatic mesoderm. Somatopleure. SpM Splanchnic mesoderm. SpP Splanchnopleure.

SoM SoP

commata) between the muscle plates (myotomes), and so it is easy to realize that each typical rib must articulate with the bodies of two adjacent vertebrae, but with the neural arch, through its trans- verse process, of only one.

The intersegmental tissue between the bodies of the vertebrae becomes the intervertebral discs and in the centre of these a pulpy