Charles Meryon: Difference between revisions

Adding local short description: "French artist", overriding Wikidata description "French artist (1821-1868)" (Shortdesc helper) |

removed Category:People with mental illnesses using HotCat This is too vague to be useful. Tag: Reverted |

||

| Line 102: | Line 102: | ||

[[Category:People with color blindness]] |

[[Category:People with color blindness]] |

||

[[Category:Artists from Paris]] |

[[Category:Artists from Paris]] |

||

[[Category:People with mental illnesses]] |

|||

Revision as of 06:31, 11 October 2020

Charles Meryon (sometimes Méryon,[1] 23 November 1821 – 13 February 1868) was a French artist who worked almost entirely in etching, as he suffered from colour blindness. Although now little-known in the English-speaking world, he is generally recognised as the most significant etcher of 19th century France. He also suffered from mental illness, dying in an asylum. His most famous works are a series of views of Paris.

Birth and childhood

Meryon's mother, Pierre-Narcisse Chaspoux, was a Parisian, born in 1791, who became a dancer in the Paris Opera in 1807 with the stage name of Narcisse Gentil. Her appearances there stop in 1814, and it was presumably about this time that she moved to London, where she became the mistress of Viscount Lowther, the future William Lowther, 2nd Earl of Lonsdale, then an unmarried Tory MP, junior minister, and friend of the Prince Regent. She had a daughter Frances (Fanny) by him in 1818. She was also friendly with Dr Charles Lewis Meryon, who had been a fellow boarder at 10 Warwick Street, Charing Cross, off Cockspur Street, around 1818. In 1821, when she was appearing as a dancer at the London Opera, Pierre-Narcisse became pregnant by Meryon, and returned to Paris with Fanny, Dr Meryon having left for Florence. Charles Meryon was born in the rue Rameau, round the corner from the then site of the Opera.[2]

His father, Dr Meryon, had been working at St Thomas' Hospital at this time, but had spent the years 1810 to 1817 in the Middle East as (at that point unqualified) doctor to the aristocratic traveller Lady Hester Stanhope, who he was later to visit in Lebanon three times, seeing her for the last time in 1838.[3] He continued to correspond with Pierre-Narcisse, and pay maintenance for his son, probably of 600 francs a year. The letters became increasingly uncomfortable, and she only found out about his marriage, which had been in 1823, by accident in 1831.[4] Equally, Pierre-Narcisse was supported by Lowther, who saw her and Fanny when he was in Paris, but she was keen to keep him unaware of the existence of Charles, although the two fathers were acquaintances in London. Both fathers apparently continued to know her under her stage name of "Narcisse Gentil".[5]

Charles was registered at birth as a "Chaspoux", and eventually (in 1829) baptised in the Church of England by the chaplain of the British Embassy in Paris. In 1824 his father legally acknowleged paternity, and he was re-registered as "Meryon", although apparently usually known as "Gentil" as a child.[6] For over a year after his birth he lived with friends of his mother some 20 kilometres outside Paris, visited not very frequently by his mother, sister and grandmother. He could walk at 9 months. He was moved back to Paris in January 1823, and from late 1825 Fanny was at a boarding school.[7]

Early adulthood

Meryon's mother brought him up, but died when he was still young, and Meryon entered the French navy, and in the corvette "Le Rhin" made the voyage round the world in the 1840s. He was already a draughtsman, for on the coast of New Zealand he made pencil drawings which he was able to employ, years afterwards, as studies for etchings of the landscape of those regions. The artistic instinct developed, and, while he was yet a lieutenant; Méryon left the navy. Finding that he was colour blind, he determined to devote himself to etching.

He entered the studio of the engraver Eugène Bléry, from whom he learnt something of technical matters, and to whom he always remained grateful. Méryon had no money, and was too proud to ask help from his family. He was forced to earn a living by doing work that was mechanical and irksome. Among learners' work, done for his own advantage, are to be counted some studies after the Dutch etchers such as Zeeman and Adriaen van de Velde. Having proved himself a skilled copyist, he began doing original work, notably a series of etchings which are the greatest embodiments of his greatest conceptions—the series called "Eaux-fortes sur Paris." These plates, executed from 1850 to 1854, are never found as a set and were never expressly published as such, but they nonetheless constituted in Méryon's mind an harmonious series.

Mature work

Besides the twenty-two etchings "sur Paris", Meryon did seventy-two etchings of one sort and another ninety-four in all being catalogued in Frederick Wedmore's Méryon and Méryon's Paris; but these include the works of his apprenticeship and of his decline, adroit copies in which his best success was in the sinking of his own individuality, and more or less dull portraits. Yet among the seventy-two prints outside his professed series there are at least a dozen famous ones. Three or four beautiful etchings of Paris do not belong to the series at all. Two or three others are devoted to the illustration of Bourges, a city in which the old wooden houses were as attractive to him for their own sakes as were the stonebuilt monuments of Paris. Generally it was when Paris engaged him that he succeeded the most. He would have done more work if the material difficulties of his life had not pressed upon him and shortened his days.

He was a bachelor, yet almost as constantly occupied with love as with work. The depth of his imagination and the surprising mastery which he achieved almost from the beginning in the technicalities of his craft were appreciated only by a few artists, critics and connoisseurs, and he could not sell his etchings or could sell them only for about lod. apiece. Disappointment told upon him, and, frugal as was his way of life, poverty must have affected him. He became subject to hallucinations. Enemies, he said, waited for him at the corners of the streets; his few friends robbed him or owed him that which they would never pay. A few years after the completion of his Paris series he was placed in the asylum at Charenton. Briefly restored to health, he came out and did a little more work, but at bottom he was exhausted. In 1867 he returned to his asylum, and died there in 1868. In middle age, just before he was confined, he associated with Félix Bracquemond and Léopold Flameng, skilled practitioners of etching. The best portrait we have of him is one by Bracquemond under which the sitter wrote that it represented “the sombre Méryon with the grotesque visage."

There are twenty-two pieces in the Eaux-fortes sur Paris. Some of them are insignificant. That is because ten out of the twenty-two were destined as headpiece, tailpiece, or running commentary on some more important plate. But each has its value, and certain of the smaller pieces throw great light on the aim of the entire set. Thus, one little plate—not a picture at all—is devoted to the record of verses made by Méryon, the purpose of which is to lament the life of Paris. Méryon aimed to illustrate its misery and poverty, as well as its splendour. His etchings are no mere views of Paris. They are “views" only so far as is compatible with their being likewise the visions of a poet and the compositions of an artist.

Méryon's epic work was coloured strongly by his personal sentiment, and affected here and there by current events — in more than one case, for instance, he hurried with particular affection to etch his impression of some old-world building which was on the point of destruction, as Napoleon III tore down buildings to reconstruct Paris with wide boulevards. Nearly every etching in the series reveals technical skill, but even the technical skill is exercised most happily in those etchings which have the advantage of impressive subjects, and which the collector willingly cherishes for their mysterious suggestiveness or for their pure beauty.

Méryon also taught; among his pupils was the etcher Gabrielle-Marie Niel.[8]

Style

The Abside de Notre Dame is the general favourite and is commonly held to be Méryon's masterpiece. Light and shade play wonderfully over the great fabric of the church, seen over the spaces of the river. As a draughtsman of architecture, Méryon was complete; his sympathy with its various styles was broad, and his work on its various styles unbiased and of equal perfection—a point in which it is curious to contrast him with J.M.W. Turner, who, in drawing Gothic architecture, often drew it with want of appreciation. It is evident that architecture must enter largely into any representation of a city, however much such representation may be a vision, and however little a chronicle. Even the architectural portion of Méryon's labour is only indirectly imaginative; to the imagination he has given freer play in his dealings with the figure, whether the people of the street or of the river or the people who, when he is most frankly or even wildly symbolical, crowd the sky.

Generally speaking, his figures are, as regards draughtsmanship, “landscape-painter's figures." They are drawn more with an eye to grace than to academic correctness. But they are not “landscape-painter's figures" at all when what we are ‘concerned with is not the method of their representation but the purpose of their introduction. They are seen then to be in exceptional accord with the sentiment of the scene. Sometimes, as in the case of La Morgue, it is they who tell the story of the picture. Sometimes, as in the case of La Rue des Mauvais Garçons—with the two passing women bent together in secret converse—they at least suggest it. And sometimes, as in L'Arche du Pont Notre Dame, it is their expressive gesture and eager action that give vitality and animation to the scene.

Dealing perfectly with architecture, and perfectly, as far as ‘concerned his peculiar purpose, with humanity in his art, Méryon was little called upon by the character of his subjects to deal with Nature. He drew trees but badly, never representing foliage happily, either in detail or in mass. But to render the characteristics of the city, it was necessary that he should know how to portray a certain kind of water—river-water, mostly sluggish--and a certain kind of sky--the grey obscured and lower sky that broods over a world of roof and chimney. This water and this sky Méryon is thoroughly master of; he notes with observant affection their changes in all lights.

In his technique, Méryon experimented variously in his brief career, and at times within individual works. In two different impressions of his Paris view La Pompe Notre Dame de Paris (1852) he could employ crisp lines through a well wiped plate without surface tone, or leave softer edges and richer darks by ample surface tone. His aesthetics were often dictated by his paper, of which he endeavored to acquire the finest available. His more defined works he printed on 'Hudelist' paper, from a mill in Hallines in the North of France, which had the uniform, smooth quality ideal for sharp images. His more gauzy works, by contrast, were printed on a softer, felt-like Morel Lavenere paper produced in Glaignes, which was highly absorbent—and pale green, which Méryon in his colour blindness would not have perceived as the typical viewer. Ultimately, however, his stated preference was for cleanly-wiped, clear prints of a uniform quality, which determination ironically positioned him against the Etching Revival he helped inspire.[9]

Value of his prints (to 1911)

It is worthwhile to note the extraordinary enhancement in the value of Méryon's prints. Probably of no other artist of genius, not even of Whistler, could there be cited within the same period a rise in prices of at all the same proportion. Thus the first state of the "Stryge" - that "with the verses" - selling under the hammer in 1873 for £5, sold again under the hammer in 1905 for £100. The first state of the "Galerie de Notre Dame" - selling in 1873 for £5 and at M. Wasset's sale in 1880 for Lii?, fetched in 1905, £52. A "Tour de l'Horloge," which two or three years after it was first issued sold for half a crown, in May 1903 fetched f70. A first state (Wedmore's, not of course M. Delteil's "first state," which, like nearly all his first states, is in fact a trial proof) of the "Saint Étienne du Mont," realizing about £2 at M. Burty's sale in 1876, realized £60 at a sale in May 1906. The second state of the "Morgue" (Wedmore) sold in 1905 for £65; and Wedmore's second of the "Abside," which used to sell throughout the seventies for £4 or £5, reached in November 1906 more than £200. At no period have even Dürers or Rembrandts risen so swiftly and steadily.

Value of his prints (to 2018)

Though while alive he sold prints for francs, in 2014 prints are for sale under US$1000. In 2018 Meryon’s etchings fetch on the market (in the U.K) from between £1,500 to £7,500 GBP

- Etchings of Paris

-

Le Petit Pont ("The Small Bridge"), 1850

-

La Pompe Notre Dame ("The Notre Dame Pump"), 1852

-

Le Pont Neuf, 1853

-

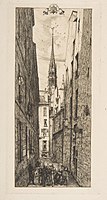

La Rue des Mauvais Garçons ("The Street of the Bad Boys"), 1854

-

Chevrier's Cold Bath Establishment, 1864

-

Tourelle, Rue de la Tixeranderie (House with a Turret, Rue de la Tixeranderie), 1852

-

Saint-Etienne-du-Mont, 1852

-

Tourelle, Rue de l'École de Médecine, 22, Paris (House with a Turret, No. 22, Street of the School of Medecine, Paris), 1861. The figures in the sky were added in later states.

-

La Rue des Chantres, 1862

- Round the world

-

Plaque in Akaroa, New Zealand, where Méryon spent three years

-

People from Wallis Island fishing, drawn 1845, etched 1863

-

New Caledonia, Large Native Hut on the Road from Balade to Puebo, drawn in 1845, etched in 1863

-

Greniers indigènes et habitations à Akaroa, presqu'Ile de Banks, ("Native Barns and Huts at Akaroa, Banks' Peninsula"), New Zealand, drawn in 1845, etched 1865

Notes

- ^ "Méryon" was common in 19th-century sources (but never for his father), but is now not usual, even in French

- ^ Collins, 1-6

- ^ Collins, 5-9

- ^ Collins, 7-11

- ^ Collins, 8, 16

- ^ Collins, 14-15

- ^ Collins, 14-17

- ^ L'art: revue mensuelle illustrée. Librairie de l'Art. 1894. pp. 352–.

- ^ van Breda, Jacobus. "Charles Meryon: Paper and Ink," Art in Print, Vol. 3 No. 3 (September–October 2013).

References

- Collins, Roger, Charles Meryon: A Life, 1999, Garton & Company, ISBN 0906030358, 9780906030356

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Méryon, Charles". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Bibliography

- Descriptive Catalogue of the Works of Méryon (London, 1879);

- Aglaus Bouvenne, Notes et souvenirs sur Charles Méryon;

- PG Hamerton, Etching and Etchers (1868);

- F. Seymour Haden, Notes on Etching;

- H Béraldi, Les Peintres graveurs du dix-neuviéme siècle;

- Baudelaire, Lettres de Baudelaire (1907);

- L. Delteil, Charles Méryon (1907)';

- Frederick Wedmore, Méryon and Méryon's Paris, with a descriptive catalogue, of the artist's work (1879; 2nd ed., 1892); and Fine Prints (1896; 2nd ed., 1905).

External links

- Prints & People: A Social History of Printed Pictures, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Charles Méryon (see index)

- Charles Méryon exhibition catalogs

- Sketchbook with Charles Méryon's drawing on the cover, ISBN 1096688646