Christian denomination: Difference between revisions

Complete revision |

|||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

==Denominations== |

==Denominations== |

||

[[Christianity]], in modern times, exists under diverse names. |

[[Christianity]], in modern times, exists under diverse names. These variously named groups, [[Anglican]]s, [[Baptist]]s, [[Catholic]]s, etc. are called '''denominations'''. |

||

[[Denominationalism]] is an ideology, which views some or all Christian groups as being, in some sense, versions of the same thing regardless of their distinguishing labels. |

[[Denominationalism]] is an ideology, which views some or all Christian groups as being, in some sense, versions of the same thing regardless of their distinguishing labels. Not all denominations teach this, however; and there are some groups which practically all others would view as [[apostasy|apostate]] or [[heretical]]: that is, not legitimate versions of Christianity. |

||

There were some [[religious denomination|denominations]] in the past which do not exist today. Examples include the [[Gnosticism|Gnostics]] (who had |

There were some [[religious denomination|denominations]] or semi-Christian groups in the past which do not exist today. Examples include the [[Gnosticism|Gnostics]] (who had believed in an [[esotericism|esoteric]] [[dualism]]), the [[Ebionite]]s (who [[veneration|venerated]] [[Christ]]'s blood relatives), and the [[Arianism|Arians]] (who believed that [[Jesus]] was a created being rather than coeternal with [[God the Father]], and who outnumbered the non-Arians for a long time within the makeup of the institutional church). It is a matter of debate as to if these groups were [[heresy|heresies]] (new [[doctrine]]s that were against the doctrines that were the true original ones), or if those beliefs were simply not defined by the larger Christian community up until that point. The greatest divisions in Christianity today however are between [[Eastern Orthodoxy]], [[Roman Catholicism]], and various denominations formed during and after the [[Protestant Reformation]]. There also exists in [[Protestantism]] various degrees of unity and division. |

||

Comparisons between denominational groups must be approached with caution. For example, in some groups, |

Comparisons between denominational groups must be approached with caution. For example, in some groups, [[congregation]]s are part of one monolithic church organization, while in other groups, each congregation is an independent [[autonomy|autonomous]] organization. Numerical comparisons are also problematic. Some groups count membership based on adult believers and [[baptism|baptized]] children of believers, while others only count adult baptized believers. In addition, there may be political motives of advocates or opponents of a particular group to inflate or deflate membership numbers through [[propaganda]] or outright deception. |

||

==Historical [[schism]]s and methods of [[taxonomy|classification schemes]]== |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

Christianity has not been a monolithic faith since the first century, if ever, and today there exist a large variety of groups that share a common history and tradition within and without [[mainstream]] Christianity. Since Christianity is the largest [[religion]] in the world (making approximately one-third of the population), it is necessary to understand the various faith traditions in terms of commonalities and differences between tradition, [[theology]], [[ecclesiology|church government]], doctrine, language, and so on. |

|||

The largest division in many classification schemes is between the families of [[Eastern Christianity|Eastern]] and [[Western Christianity]]. After these two larger families come distinct branches of Christianity. Most classification schemes list six (in order of size: [[Catholicism]], [[Protestantism]], [[Eastern Orthodoxy]], [[Anglicanism]], [[Oriental Orthodoxy]], and [[Assyrian Church of the East|Assyrians]]). Others may include [[Restorationism]] as a seventh, but classically this is included among Protestant movements. After these branches comes denominational families. In some traditions, these families are precisely defined (such as the autocephalous churches in both Orthodox branches), in others, they may be loose ideological groups with overlap (this is especially the case in Protestantism, which includes [[Anabaptists]], [[Adventism|Adventists]], [[Baptists]], [[Congregationalism|Congregationalists]], [[Pentecostalism|Pentecostals]], |

|||

| ⚫ | [[Catholicism]] and [[Protestantism]] are the two major divisions of [[Christianity]] in the Western world. For example, the [[Baptist]], [[ |

||

[[Lutheranism|Lutherans]], [[Methodism|Methodists]], [[Presbyterianism|Presbyterians]], [[Reformed churches]], and possibly others, depending on who is organizing the scheme. From there come denominations, which in the West, have complete independence to establish doctrine (for instance, national churches in the [[Anglican Communion]] or the [[Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod]] in [[Lutheranism]]). At this point, the scheme becomes more difficult to apply to the Eastern churches and Catholic faiths, due to their top-down hierarchical structures. More precise units after denominations include kinds of regional councils and individual [[congregation]]s and church bodies. |

|||

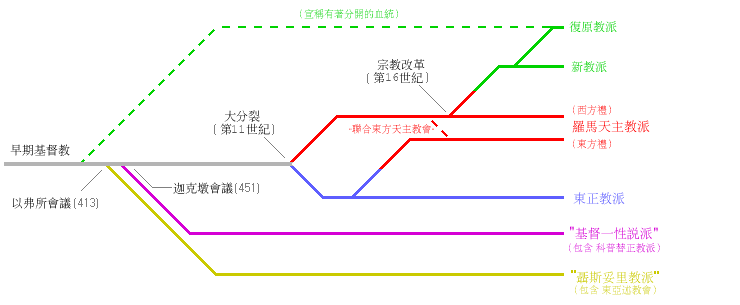

[[Image:Christian-lineage.png|framed|center|A schematic of Christian denominational taxonomy.]] |

|||

| ⚫ | One central tenet of Catholicism is its literal adherence to [[apostolic succession]]. "[[Apostle]]" means "one who is sent out." Jesus commissioned the first twelve apostles (see [[Biblical Figures]] for the list of the Twelve), and they, in turn laid hands on subsequent church leaders to ordain (commission) them for ministry. In this manner, Catholics trace their ordained ministers all the way back to the original Twelve. |

||

The initial differences between the East and West traditions stem to socio-[[culture|cultural]] and [[linguistics|linguistic]] divisions in and between the [[Roman Empire|Roman]] and [[Byzantine Empire]]s. Since the West (that is, [[Europe]]) spoke [[Latin]] as its ''[[lingua franca]]'' and the East (the [[Middle East]], [[Asia]], and northern [[Africa]]) largely used [[Koine Greek]] to transmit writings, theological developments were difficult to translate from one branch to the other. In the course of [[ecumenical council]]s (large gatherings of Christian leaders), some church bodies split from the larger family of Christianity. Many earlier [[heresy|heretical]] groups either died off for lack of followers and/or suppression by the church at large (such as [[Apollinarianism|Apollinarians]], [[Montanism|Montanists]], and [[Ebionites]]). |

|||

Protestantism may be traced in terms of [[intellectual history]], to a development during a period of over three hundred years, beginning with the work of [[John Wyclif]], then [[Jan Hus]], and finally [[Martin Luther]] and the other Magisterial Reformers. Wyclif was a professor at the [[University of Oxford]]. Hus taught at the [[University of Prague]]. This area had been [[Eastern Orthodoxy|Orthodox]], and had been [[christianization|forcibly converted]] to Roman Catholicism. Hus tried to return the Church in Bohemia and Moravia to classical orthodoxy by having the liturgy in the language of the people, married priests, communion in both kinds (bread and wine) for lay people, and the abolition of indulgences and the idea of [[purgatory]]. Hus's work resulted in the formation of the [[Moravian Church]] [http://www.moravian.org]. Later Protestants' occasional rediscovery of the Moravian brethren was important at critical times, in the development of Protestantism. |

|||

The first significant, lasting split in historic Christianity came from the [[Assyrian Church of the East]], who left following the [[Christology|Christological]] controversy over [[Nestorianism]] in [[431]] (the Assyrians in 1994 released a common Christological statement with the [[Roman Catholicism|Catholic church]]). Today, the Assyrian and Catholic churches view this schism as largely linguistic, due to problems of translating very delicate and precise terminology from Latin to [[Aramaic]] and vice-versa (see [[Council of Ephesus]]). Following the [[Council of Chalcedon]] in [[451]], the next large split came with a the [[Syriac Orthodox Church|Syrian]] and [[Coptic Christianity|Alexandrian]] (Egyptian or Coptic) churches dividing themselves, with the dissenting churches becoming today's [[Oriental Orthodoxy]]. (A similar Christological statement was made between [[Pope John Paul II]] and Syriac patriarch [[Ignatius Zakka I Iwas]]). |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

Although the church as a whole didn't experience any major divisions for centuries afterward, the Eastern and Western groups drifted until the point where patriarchs from both families [[excommunication|excommunicated]] one another in about [[1054]] in what is known as the [[East-West Schism|Great Schism]]. The political and theological reasons for the schism are complex, but one major controversy was the issue of [[Primacy of the Roman Pontiff|papal primacy]]: the West insisted that the [[Patriarch of Rome]] held a special position of authority over other patriarchs (in [[Alexandria]], [[Antioch]], [[Constantinople]], and [[Jerusalem]]), while the East taught that all patriarchs were co-equal and had no authority over other jurisdictions. Either church considers the other to be the catalyst for the split, and it was only until the papacy of Pope John Paul II that significant reforms were made to mend the relationship between the two. |

|||

| ⚫ | Some denominations which arose alongside the Western Christian tradition consider themselves Christian, but neither Catholic nor wholly Protestant, |

||

In Western Christianity, there were a handful of geographically-isolated movements that preceded the spirit of the [[Protestant Reformation]]. In [[Italy]], [[Peter Waldo]] founded the [[Waldensians]] in [[12th century]] [[France]]. This movement has largely been absorbed by modern-day Protestant groups. In [[Bohemia]], an Orthodox region, the [[Vatican]] (unlike today's [[Holy See]], a much more powerful land empire) took over the region and [[conversion|converted]] it to the Catholic faith. A movement in the early [[15th century]] by [[Jan Hus]] called the [[Hussite]]s defied Catholic [[dogma]] and still exists to this day (alternately known as the [[Moravian]]s). By far, the largest and most devastating pre-Reformation split was when [[Henry VIII of England]] declared himself the head of the [[Church of England]] with the [[Act of Supremacy]] in [[1531]], founding [[Anglicanism]] as a separate branch of Christian faith. |

|||

A huge schism was unintentionally founded by the posting of [[Martin Luther]]'s [[95 Theses]] in [[Saxony]] on [[October 31]], [[1517]]. Initially written as a set of grievances to spur the Catholic church into reforming itself, rather than beginning a new [[sect]], Luther's writings combined with the work of [[Switzerland|Swiss]] theologian [[Huldrych Zwingli]] and French theologian and politician [[John Calvin]] instigating a rift in European Christianity that created today's second-largest branch of Christianity after Catholicism itself, [[Protestantism]]. |

|||

Unlike the other branches (Catholicism, Eastern and Oriental Orthodoxy, the Assyrians, and Anglicans), Protestants are a general movement that has no internal governing structure. As such, diverse groups such as [[Presbyterianism|Presbyterians]], [[Reformed churches]], [[Lutheranism|Lutherans]], [[Methodism|Methodists]], [[Congregationalism|Congregationalists]], [[Anabaptists]], [[Baptists]], [[Adventism|Adventists]], [[Pentecostalism|Pentecostals]], and even possibly [[Restorationism|Restorationists]] (depending on one's classification scheme) are all a part of the same family. The largest amount of new churches and denominations have come from Protestantism in its first four hundred years, compared to the millennium and a half prior in all of [[Christendom]]. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | [[Catholicism]] and [[Protestantism]] are the two major divisions of [[Christianity]] in the Western world, if [[Anglicanism]] is included as a part of the latter. For example, the [[Baptist]], [[Methodism|Methodist]], and [[Lutheranism|Lutheran]] churches are generally considered to be Protestant faiths, although strictly speaking, of these three the Lutheran denomination is the only one of these founded as a "protest" against Catholicism. [[Anglican Church|Anglicanism]] is generally classified as Protestant, but since the "Tractarian" or [[Oxford Movement]] of the 19th century, led by [[John Henry Newman]], Anglican writers emphasize a more catholic understanding of the church and characterize it as more properly understood as its own tradition — a ''via media'' ("middle way"), ''both'' Protestant and Catholic. |

||

| ⚫ | One central tenet of Catholicism is its literal adherence to [[apostolic succession]]. "[[Apostle]]" means "one who is sent out." Jesus commissioned the first twelve apostles (see [[Biblical Figures]] for the list of the Twelve), and they, in turn laid hands on subsequent church leaders to ordain (commission) them for ministry. In this manner, Catholics trace their ordained ministers all the way back to the original [[Apostle|Twelve]]. Catholics are distinct in their belief that the [[Pope]] has authority which can be traced directly to the apostle [[Saint Peter|Peter]]. There are small schismatic groups from the Catholic faith, such as the [[Old Catholic Church]] which rejected the definition of [[papal infallibility]] at the [[First Vatican Council]], and [[Anglo-Catholicism|Anglo-Catholics]], [[Anglican Church|Anglicans]] who believe that Anglicanism is a continuation of historical Catholicism and who incorporate many Catholic beliefs and practices. Catholicism is widely referred to as [[Roman Catholicism]], but this title is an inaccurate reflection of the make-up of the Catholic faith, as there are other religious [[rite]]s than the [[Latin Rite]] (which makes up the vast majority of believers). These smaller groups are included in the [[Eastern Rite]], and is largely composed of Eastern Christian groups that defected from their tradition to submit to papal authority. Catholicism is a top-down hierarchical faith in which supreme authority for matters of faith and practice are the exclusive domain of the Pope. |

||

| ⚫ | Since Protestantism does not represent a unified body of believers, but a faith tradition which has itself split several times, it is more often understood in large denominational families. Each Protestant movement has developed freely, and many have split over theological issues. For instance, a number of movements that grew out of spiritual revivals, like [[Methodism]] and [[Pentecostalism]]. Doctrinal issues and matters of [[conscience]] have also divided Protestants. The [[Anabaptist]] tradition, made up of the [[Amish]] and [[Mennonites]], rejected the Catholic and Lutheran doctrines of [[pedobaptism|infant baptism]]; this tradition is also noted for its belief in [[pacifism]]. The measure of mutual acceptance between the denominations and movements varies, but is growing largely due to the [[ecumenism|ecumenical movement]] in the [[20th century]] and overarching Christian bodies such as the [[World Council of Churches]]. Protestant [[theology]] for each [[religious denomination|denomination]] is usually guarded by local church councils. |

||

===Eastern groups=== |

===Eastern groups=== |

||

In the Eastern world, the largest body of believers is the [[Eastern Orthodoxy]]. The Eastern Orthodox Church also believes it is the continuation of the original Christian church established by [[Jesus]]. According to the Eastern Churches' understanding of Papal primacy, the [[Pope|bishop of Rome]] was first in honor among the bishops, but possessed no direct authority over [[diocese]]s other than his own. Consequently, each church in the Eastern Orthodoxy is [[autocephaly|autocephalous]], and is internally responsible for matters of doctrine and practice. Today, the [[Patriarch of Constantinople]] (modern-day [[Istanbul]], [[Turkey]]) is known as the [[Ecumenical Patriarch]], and holds the title of honor among other [[bishop]]s (see [[primus inter pares]], or first among equals). In addition to the four ancient churches there are approximately 10 others organized more or less along national lines (there is some controversy over whether or not the [[Orthodox Church in America]] is or should be autocephalous). The largest of these, and the largest Orthodox Church overall, is the [[Russian Orthodox Church]]. Many of these groups are represented as independent ecclesiastical bodies in America who, for the most part, are still in [[full Communion]] with each other. In addition, smaller Orthodox communities have a large degree of internal responsibility, known as [[autonomy]], but are under the authority of another regional church. Small schisms exist today with "[[Old calendarists]]" groups and national churches that are not in communion with other Orthodox Churches (such as the [[Macedonian Orthodox Church]] and [[Montenegrin Orthodox Church]]). |

|||

The [[Oriental Orthodoxy|Oriental Orthodox]], organizes its church in a similar manner, with six national autocephalous groups and two autonomous bodies. Although the region of modern-day [[Ethiopia]] and [[Eritrea]] has had a strong body of believers since the infancy of Christianity, these regions only gained autocephaly in [[1963]] and [[1994]] respectively. Since these groups are relatively obscure in the West, literature on them has sometimes included the Assyrian church as a part of the Oriental Orthodox Communion, but the Assyrians have maintained theological, cultural, and ecclesiastical independence from all other Christian bodies since [[431]]. The church is administered in a hierarchical model not entirely unlike the Catholics, with the head of the church being the [[List of Patriarchs of Babylon|Patriarch Catholicos of Babylon]], currently HH [[Mar Dinkha IV]]. Due to [[oppression]], the church's headquarters is in [[Chicago, Illinois]], rather than [[Assyria]] (northern [[Iraq]] and part of [[Iran]]). Some believers have remained in the Middle East, though, and a small congregation still exists due to missionary efforts of the [[7th century|7th]] and [[8th century|8th centuries]] in [[Peoples Republic of China|China]]. Even within this small group, there is a rival Catholicos (Patriarch) in [[California]]. |

|||

===Non-mainstream Christianity=== |

|||

While a precise definition of what constitutes mainstream Christianity is difficult at best, there are some groups that fall outside of what is popularly construed to be Christian groups, but share some manner of historical connection with the larger community of Christians. |

|||

One group which has maintained its Jewish identity alongside an acceptance of Jesus as the [[Messiah]] and the [[New Testament]] as authoritative are [[Messianic Jews]], also called Hebrew Christians. Since the founding of the church, there have been Jewish elements retained by particular groups that wanted to retain their national heritage alongside the [[Gospel]] message. In fact, the first council was called in Jerusalem to address just this issue, and the deciding opinion was written by Christ's brother [[James the Just]], the first bishop of Jerusalem and a pivotal figure in the Christian movement. The best known group of Messianic Jews in [[United States|America]] today is [[Jews for Jesus]], and due to the entirely different history of such movements and groups, they defy any simply classification scheme. |

|||

| ⚫ | Some denominations which arose alongside the Western Christian tradition consider themselves Christian, but neither Catholic nor wholly Protestant, such as the [[Religious Society of Friends|Religious Society of Friends, or Quakers,]]. Quakerism began as a mystical and evangelical Christian movement in 17th century [[England]], eschewing priests and all formal Anglican or Catholic sacraments in their worship, including many of those practices that remained among the stridently Protestant [[Puritan]]s such as baptism with water. Like the Mennonites, Quakers traditionally refrain from participation in war. |

||

| ⚫ | Other faith traditions claim not to be descended from any of these groups directly. [[Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints|The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints]], for instance, is often grouped with the [[Protestant]] churches, but does not characterize itself as Protestant. Its origination during the [[Second Great Awakening]] parallels the founding of numerous other indigenous American religions, especially in the [[Burned-over district]] of western [[New York]] state, and in the western territories of the [[United States]], including the [[Millerites|Adventist]] movement and the [[Restoration Movement]] (sometimes called "Campbellites" or "Stone-Campbell churches", which include the [[Christian Church (Disciples of Christ)]] and the [[Church of Christ]]). Each of these groups, founded within fifty years of one another, originally claimed to be an unprecedented, late restoration of the primitive Christian church. |

||

In the Eastern world (Eastern Europe, Asia) the primary representative of [[Christianity]] is [[Eastern Orthodoxy]]. The Eastern Orthodox Church also believes it is the continuation of the original Christian church established by [[Jesus]]. Originally there were five main centers of Christianity in the ancient world: [[Rome]], [[Constantinople]], [[Alexandria]], [[Antioch]], and [[Jerusalem]]. According to the Eastern Churches' understanding of Papal primacy, the [[Pope|bishop of Rome]] was first in honor among the bishops, but possessed no direct authority over [[diocese|dioceses]] other than his own. In the [[East-West Schism|Great Schism]], conventionally dated to [[1054]], the Eastern Churches severed [[communion]] with Rome over a number of issues centered on the differing understanding of Papal primacy. The four other Churches remained in communion with each other and still exist today along with less prestigious, but often more populous, self-governing or "autocephalous" Churches organized more or less along national lines. The largest of these, and the largest Orthodox Church overall, is the [[Russian Orthodox Church]]. Many of these groups are represented as independent ecclesiastical bodies in America who, for the most part, are still in [[full Communion]] with each other. There exist significant [[theology|theological]] differences between the Orthodox Church and Western Christianity. |

|||

| ⚫ | [[Christianity]], even in its infancy as a [[Judaism|Jewish]] sect, rejected ethnic definition. It was conceived and grew as an international religion with global ambitions, spreading rapidly from [[Judea]] to nations and people all over the world. Doctrines, rather than ethnicity, define essential Christianity - even where ethnic groups have been Christian for generations. The multiplicity of communities of faith may be partly accounted for by the definition of Christianity according to specific points of indispensable doctrine, the denial of which sets the [[heresy|heretic]], or apostate, outside of the "Church", where perhaps he is accepted by another "Church" holding doctrines compatible with his own. |

||

The Eastern Orthodox Churches accepted the [[Council of Chalcedon|Chalcedonian]] [[dogma]] on the nature of Jesus, which was also accepted by the Western branch of the church; while the [[Oriental Orthodox]] rejected it. The [[Oriental Orthodoxy|Oriental Orthodox]], as the term is sometimes used in the West, comprise chiefly the [[Monophysites]] (e.g. the [[Coptic Christianity|Coptic church]], the [[Armenian Apostolic Church]], the [[Syria|Syrian]] [[Jacobite (Orthodox)|Jacobites]], the [[Ethiopian Orthodox Church]]), the [[Nestorians]] (e.g. the [[Assyrian Church of the East]]), and several others. However, the Assyrians and those who share their doctrine are not accepted as part of the [[Oriental Orthodoxy#Oriental Orthodox Communion|Oriental Orthodox Communion]]. |

|||

| ⚫ | Points of distinctive doctrine may be a very small number of simple propositions, or very numerous and difficult to explain, depending on the group. Some groups are defined relatively statically, and others have changed their definitions dramatically over time. As an example, before the [[The Age of Enlightenment|Enlightenment]], Christian teachers who denied the doctrine of the [[Holy Trinity]] (a widely held doctrine about the nature of [[God the Father]], [[God the Son|Jesus the Son]], and the [[Holy Spirit]] formulated from New Testament passages in [[325]]), would be cast out of their churches, and at times exiled or otherwise deprived of the protection of law. In later times, the doctrine of the Trinity is considered a false doctrine according to groups such as [[Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints|The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints]], and the [[Jehovahs Witnesses|Jehovah's Witnesses]] (representing tens of millions of believers combined). Similar movements coalesced to form today's [[Unitarian-Universalism]], which formally renounced Christian origins in [[1961]], and exist as a separate religious body. Due to the virtual absence of any formalized doctrine, though, there are several UU's who still self-identify as Christians, although they are certainly the minority. |

||

===Other groups=== |

|||

Another family of (semi-)Christian churches are grouped together under the banner of "[[New Thought]]" churches. Although the terminology is inaccurate, these churches share a [[metaphysics|metaphysical]] or [[mysticism|mystical]] predisposition and understanding of the [[Bible]]. One of the oldest metaphysical Christian groups are the [[Swedenborgianism|Swedenborgians]], founded on the teachings of [[Emanuel Swedenborg]] in [[1787]]. The latter part of the 19th century also saw the founding of the [[Church of Christ, Scientist]] ("Christian Scientists") by [[Mary Baker Eddy]], and [[Spiritism]] by [[Allan Kardec]]. Lastly, the mystical elements of [[Yorùbá]], an African [[animism|animistic]] tradition combined with Roman Catholicism via Afro-Cuban slaves, forming [[Lukum%C3%AD]] (more well-known in America by its branch Santeria). |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

Two movements which are entirely unrelated in their founding share a common element of an additional Messiah or incarnation of Christ: the [[Unification Church]] and the [[Rastafari movement]]. These groups would also fall outside of traditional [[taxonomy|taxonomies]] of Christian groups. |

|||

| ⚫ | [[Christianity]], even in its infancy as a [[Judaism|Jewish]] sect, rejected ethnic definition. |

||

| ⚫ | There are also some Christians that reject the church altogether, believing that the only authority they should follow is God as embodied in Jesus. [[Christian anarchism|Christian anarchists]] feel that earthly authority such as government, or indeed the established church do not and should not have power over them. They also oppose the use of physical force in any circumstance and believe in [[nonviolence]]. [[Leo Tolstoy]] who wrote ''[[The Kingdom of God is Within You]]'' [http://www.kingdomnow.org/withinyou.html] was a Christian anarchist. |

||

| ⚫ | Points of distinctive doctrine may be a very small number of simple propositions, or very numerous and difficult to explain, depending on the group. |

||

One peculiar body presents virtually the last [[Gnosticism|Gnostic]] group in existence. The [[Mandaeanism|Mandaeans]] were discovered in obscurity on the coast of modern-day [[Iraq]] and [[Iran]] by [[Portugal|Portuguese]] [[missionary|missionaries]] in the [[14th century]]. They were erroneously identified as "Christians of [[John the Baptist]]", but reject [[Jesus]] [[Christ]] entirely as a false prophet, and following [[esotericism|esoteric]] teachings they claim come from John the Baptist himself. Another small Gnostic group which purports itself to be a "[[Buddhism|Buddhist]] branch of original [[Christianity]]" are the [http://www.essenes.net/ Essenes]. These [[syncretism|syncretists]] are entirely unrelated to the ancient [[Judaism|Jewish]] sect of the same name. |

|||

Others, such as some [[Unitarian Universalism|Unitarian Universalists]], only consider ''themselves'' as borderline Christians, since Jesus is not pivotal to their belief system. [[Religious Society of Friends|Quakerism]], which does not consider itself to belong to any of the above groupings, began as a Christian movement, and many branches within this denomination remain strongly Christian, while others branches have become borderline Christian and may even include people who do not consider themselves Christian. In addition, Christianity has partly inspired other religions, like early [[Islam]] and later [[Bahá'í Faith|Bahá'is]], whose adherents do not consider themselves Christians but do consider Jesus to be a prophet (and in the case of Islam, the [[Messiah]] as well). |

|||

In addition, Christianity has partly inspired other religions, like early [[Islam]] and later [[Bahá'í Faith|Bahá'is]], whose adherents do not consider themselves Christians but do consider Jesus to be a prophet (and in the case of Islam, the [[Messiah]] as well). |

|||

| ⚫ | There are also some Christians that reject the church altogether, believing that the only authority they should follow is God as embodied in Jesus. |

||

Considering this diversity, it may be impossible to define what Christianity is without either rejecting all definitions, or adopting a particular definition as authoritative and thus excluding others. In terms of the modern aim of scientific and objective definition, both options are considered problematic. |

Considering this diversity, it may be impossible to define what Christianity is without either rejecting all definitions, or adopting a particular definition as authoritative and thus excluding others. In terms of the modern aim of scientific and objective definition, both options are considered problematic. |

||

Revision as of 04:18, 2 August 2005

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

A denomination in the Christian sense is an identifiable religious body, organization under a common name, structure, and/or doctrine.

Denominations

Christianity, in modern times, exists under diverse names. These variously named groups, Anglicans, Baptists, Catholics, etc. are called denominations.

Denominationalism is an ideology, which views some or all Christian groups as being, in some sense, versions of the same thing regardless of their distinguishing labels. Not all denominations teach this, however; and there are some groups which practically all others would view as apostate or heretical: that is, not legitimate versions of Christianity.

There were some denominations or semi-Christian groups in the past which do not exist today. Examples include the Gnostics (who had believed in an esoteric dualism), the Ebionites (who venerated Christ's blood relatives), and the Arians (who believed that Jesus was a created being rather than coeternal with God the Father, and who outnumbered the non-Arians for a long time within the makeup of the institutional church). It is a matter of debate as to if these groups were heresies (new doctrines that were against the doctrines that were the true original ones), or if those beliefs were simply not defined by the larger Christian community up until that point. The greatest divisions in Christianity today however are between Eastern Orthodoxy, Roman Catholicism, and various denominations formed during and after the Protestant Reformation. There also exists in Protestantism various degrees of unity and division.

Comparisons between denominational groups must be approached with caution. For example, in some groups, congregations are part of one monolithic church organization, while in other groups, each congregation is an independent autonomous organization. Numerical comparisons are also problematic. Some groups count membership based on adult believers and baptized children of believers, while others only count adult baptized believers. In addition, there may be political motives of advocates or opponents of a particular group to inflate or deflate membership numbers through propaganda or outright deception.

Historical schisms and methods of classification schemes

Christianity has not been a monolithic faith since the first century, if ever, and today there exist a large variety of groups that share a common history and tradition within and without mainstream Christianity. Since Christianity is the largest religion in the world (making approximately one-third of the population), it is necessary to understand the various faith traditions in terms of commonalities and differences between tradition, theology, church government, doctrine, language, and so on.

The largest division in many classification schemes is between the families of Eastern and Western Christianity. After these two larger families come distinct branches of Christianity. Most classification schemes list six (in order of size: Catholicism, Protestantism, Eastern Orthodoxy, Anglicanism, Oriental Orthodoxy, and Assyrians). Others may include Restorationism as a seventh, but classically this is included among Protestant movements. After these branches comes denominational families. In some traditions, these families are precisely defined (such as the autocephalous churches in both Orthodox branches), in others, they may be loose ideological groups with overlap (this is especially the case in Protestantism, which includes Anabaptists, Adventists, Baptists, Congregationalists, Pentecostals, Lutherans, Methodists, Presbyterians, Reformed churches, and possibly others, depending on who is organizing the scheme. From there come denominations, which in the West, have complete independence to establish doctrine (for instance, national churches in the Anglican Communion or the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod in Lutheranism). At this point, the scheme becomes more difficult to apply to the Eastern churches and Catholic faiths, due to their top-down hierarchical structures. More precise units after denominations include kinds of regional councils and individual congregations and church bodies.

The initial differences between the East and West traditions stem to socio-cultural and linguistic divisions in and between the Roman and Byzantine Empires. Since the West (that is, Europe) spoke Latin as its lingua franca and the East (the Middle East, Asia, and northern Africa) largely used Koine Greek to transmit writings, theological developments were difficult to translate from one branch to the other. In the course of ecumenical councils (large gatherings of Christian leaders), some church bodies split from the larger family of Christianity. Many earlier heretical groups either died off for lack of followers and/or suppression by the church at large (such as Apollinarians, Montanists, and Ebionites).

The first significant, lasting split in historic Christianity came from the Assyrian Church of the East, who left following the Christological controversy over Nestorianism in 431 (the Assyrians in 1994 released a common Christological statement with the Catholic church). Today, the Assyrian and Catholic churches view this schism as largely linguistic, due to problems of translating very delicate and precise terminology from Latin to Aramaic and vice-versa (see Council of Ephesus). Following the Council of Chalcedon in 451, the next large split came with a the Syrian and Alexandrian (Egyptian or Coptic) churches dividing themselves, with the dissenting churches becoming today's Oriental Orthodoxy. (A similar Christological statement was made between Pope John Paul II and Syriac patriarch Ignatius Zakka I Iwas).

Although the church as a whole didn't experience any major divisions for centuries afterward, the Eastern and Western groups drifted until the point where patriarchs from both families excommunicated one another in about 1054 in what is known as the Great Schism. The political and theological reasons for the schism are complex, but one major controversy was the issue of papal primacy: the West insisted that the Patriarch of Rome held a special position of authority over other patriarchs (in Alexandria, Antioch, Constantinople, and Jerusalem), while the East taught that all patriarchs were co-equal and had no authority over other jurisdictions. Either church considers the other to be the catalyst for the split, and it was only until the papacy of Pope John Paul II that significant reforms were made to mend the relationship between the two.

In Western Christianity, there were a handful of geographically-isolated movements that preceded the spirit of the Protestant Reformation. In Italy, Peter Waldo founded the Waldensians in 12th century France. This movement has largely been absorbed by modern-day Protestant groups. In Bohemia, an Orthodox region, the Vatican (unlike today's Holy See, a much more powerful land empire) took over the region and converted it to the Catholic faith. A movement in the early 15th century by Jan Hus called the Hussites defied Catholic dogma and still exists to this day (alternately known as the Moravians). By far, the largest and most devastating pre-Reformation split was when Henry VIII of England declared himself the head of the Church of England with the Act of Supremacy in 1531, founding Anglicanism as a separate branch of Christian faith.

A huge schism was unintentionally founded by the posting of Martin Luther's 95 Theses in Saxony on October 31, 1517. Initially written as a set of grievances to spur the Catholic church into reforming itself, rather than beginning a new sect, Luther's writings combined with the work of Swiss theologian Huldrych Zwingli and French theologian and politician John Calvin instigating a rift in European Christianity that created today's second-largest branch of Christianity after Catholicism itself, Protestantism.

Unlike the other branches (Catholicism, Eastern and Oriental Orthodoxy, the Assyrians, and Anglicans), Protestants are a general movement that has no internal governing structure. As such, diverse groups such as Presbyterians, Reformed churches, Lutherans, Methodists, Congregationalists, Anabaptists, Baptists, Adventists, Pentecostals, and even possibly Restorationists (depending on one's classification scheme) are all a part of the same family. The largest amount of new churches and denominations have come from Protestantism in its first four hundred years, compared to the millennium and a half prior in all of Christendom.

Western groups

Catholicism and Protestantism are the two major divisions of Christianity in the Western world, if Anglicanism is included as a part of the latter. For example, the Baptist, Methodist, and Lutheran churches are generally considered to be Protestant faiths, although strictly speaking, of these three the Lutheran denomination is the only one of these founded as a "protest" against Catholicism. Anglicanism is generally classified as Protestant, but since the "Tractarian" or Oxford Movement of the 19th century, led by John Henry Newman, Anglican writers emphasize a more catholic understanding of the church and characterize it as more properly understood as its own tradition — a via media ("middle way"), both Protestant and Catholic.

One central tenet of Catholicism is its literal adherence to apostolic succession. "Apostle" means "one who is sent out." Jesus commissioned the first twelve apostles (see Biblical Figures for the list of the Twelve), and they, in turn laid hands on subsequent church leaders to ordain (commission) them for ministry. In this manner, Catholics trace their ordained ministers all the way back to the original Twelve. Catholics are distinct in their belief that the Pope has authority which can be traced directly to the apostle Peter. There are small schismatic groups from the Catholic faith, such as the Old Catholic Church which rejected the definition of papal infallibility at the First Vatican Council, and Anglo-Catholics, Anglicans who believe that Anglicanism is a continuation of historical Catholicism and who incorporate many Catholic beliefs and practices. Catholicism is widely referred to as Roman Catholicism, but this title is an inaccurate reflection of the make-up of the Catholic faith, as there are other religious rites than the Latin Rite (which makes up the vast majority of believers). These smaller groups are included in the Eastern Rite, and is largely composed of Eastern Christian groups that defected from their tradition to submit to papal authority. Catholicism is a top-down hierarchical faith in which supreme authority for matters of faith and practice are the exclusive domain of the Pope.

Since Protestantism does not represent a unified body of believers, but a faith tradition which has itself split several times, it is more often understood in large denominational families. Each Protestant movement has developed freely, and many have split over theological issues. For instance, a number of movements that grew out of spiritual revivals, like Methodism and Pentecostalism. Doctrinal issues and matters of conscience have also divided Protestants. The Anabaptist tradition, made up of the Amish and Mennonites, rejected the Catholic and Lutheran doctrines of infant baptism; this tradition is also noted for its belief in pacifism. The measure of mutual acceptance between the denominations and movements varies, but is growing largely due to the ecumenical movement in the 20th century and overarching Christian bodies such as the World Council of Churches. Protestant theology for each denomination is usually guarded by local church councils.

Eastern groups

In the Eastern world, the largest body of believers is the Eastern Orthodoxy. The Eastern Orthodox Church also believes it is the continuation of the original Christian church established by Jesus. According to the Eastern Churches' understanding of Papal primacy, the bishop of Rome was first in honor among the bishops, but possessed no direct authority over dioceses other than his own. Consequently, each church in the Eastern Orthodoxy is autocephalous, and is internally responsible for matters of doctrine and practice. Today, the Patriarch of Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul, Turkey) is known as the Ecumenical Patriarch, and holds the title of honor among other bishops (see primus inter pares, or first among equals). In addition to the four ancient churches there are approximately 10 others organized more or less along national lines (there is some controversy over whether or not the Orthodox Church in America is or should be autocephalous). The largest of these, and the largest Orthodox Church overall, is the Russian Orthodox Church. Many of these groups are represented as independent ecclesiastical bodies in America who, for the most part, are still in full Communion with each other. In addition, smaller Orthodox communities have a large degree of internal responsibility, known as autonomy, but are under the authority of another regional church. Small schisms exist today with "Old calendarists" groups and national churches that are not in communion with other Orthodox Churches (such as the Macedonian Orthodox Church and Montenegrin Orthodox Church).

The Oriental Orthodox, organizes its church in a similar manner, with six national autocephalous groups and two autonomous bodies. Although the region of modern-day Ethiopia and Eritrea has had a strong body of believers since the infancy of Christianity, these regions only gained autocephaly in 1963 and 1994 respectively. Since these groups are relatively obscure in the West, literature on them has sometimes included the Assyrian church as a part of the Oriental Orthodox Communion, but the Assyrians have maintained theological, cultural, and ecclesiastical independence from all other Christian bodies since 431. The church is administered in a hierarchical model not entirely unlike the Catholics, with the head of the church being the Patriarch Catholicos of Babylon, currently HH Mar Dinkha IV. Due to oppression, the church's headquarters is in Chicago, Illinois, rather than Assyria (northern Iraq and part of Iran). Some believers have remained in the Middle East, though, and a small congregation still exists due to missionary efforts of the 7th and 8th centuries in China. Even within this small group, there is a rival Catholicos (Patriarch) in California.

Non-mainstream Christianity

While a precise definition of what constitutes mainstream Christianity is difficult at best, there are some groups that fall outside of what is popularly construed to be Christian groups, but share some manner of historical connection with the larger community of Christians.

One group which has maintained its Jewish identity alongside an acceptance of Jesus as the Messiah and the New Testament as authoritative are Messianic Jews, also called Hebrew Christians. Since the founding of the church, there have been Jewish elements retained by particular groups that wanted to retain their national heritage alongside the Gospel message. In fact, the first council was called in Jerusalem to address just this issue, and the deciding opinion was written by Christ's brother James the Just, the first bishop of Jerusalem and a pivotal figure in the Christian movement. The best known group of Messianic Jews in America today is Jews for Jesus, and due to the entirely different history of such movements and groups, they defy any simply classification scheme.

Some denominations which arose alongside the Western Christian tradition consider themselves Christian, but neither Catholic nor wholly Protestant, such as the Religious Society of Friends, or Quakers,. Quakerism began as a mystical and evangelical Christian movement in 17th century England, eschewing priests and all formal Anglican or Catholic sacraments in their worship, including many of those practices that remained among the stridently Protestant Puritans such as baptism with water. Like the Mennonites, Quakers traditionally refrain from participation in war.

Other faith traditions claim not to be descended from any of these groups directly. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, for instance, is often grouped with the Protestant churches, but does not characterize itself as Protestant. Its origination during the Second Great Awakening parallels the founding of numerous other indigenous American religions, especially in the Burned-over district of western New York state, and in the western territories of the United States, including the Adventist movement and the Restoration Movement (sometimes called "Campbellites" or "Stone-Campbell churches", which include the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) and the Church of Christ). Each of these groups, founded within fifty years of one another, originally claimed to be an unprecedented, late restoration of the primitive Christian church.

Christianity, even in its infancy as a Jewish sect, rejected ethnic definition. It was conceived and grew as an international religion with global ambitions, spreading rapidly from Judea to nations and people all over the world. Doctrines, rather than ethnicity, define essential Christianity - even where ethnic groups have been Christian for generations. The multiplicity of communities of faith may be partly accounted for by the definition of Christianity according to specific points of indispensable doctrine, the denial of which sets the heretic, or apostate, outside of the "Church", where perhaps he is accepted by another "Church" holding doctrines compatible with his own.

Points of distinctive doctrine may be a very small number of simple propositions, or very numerous and difficult to explain, depending on the group. Some groups are defined relatively statically, and others have changed their definitions dramatically over time. As an example, before the Enlightenment, Christian teachers who denied the doctrine of the Holy Trinity (a widely held doctrine about the nature of God the Father, Jesus the Son, and the Holy Spirit formulated from New Testament passages in 325), would be cast out of their churches, and at times exiled or otherwise deprived of the protection of law. In later times, the doctrine of the Trinity is considered a false doctrine according to groups such as The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and the Jehovah's Witnesses (representing tens of millions of believers combined). Similar movements coalesced to form today's Unitarian-Universalism, which formally renounced Christian origins in 1961, and exist as a separate religious body. Due to the virtual absence of any formalized doctrine, though, there are several UU's who still self-identify as Christians, although they are certainly the minority.

Another family of (semi-)Christian churches are grouped together under the banner of "New Thought" churches. Although the terminology is inaccurate, these churches share a metaphysical or mystical predisposition and understanding of the Bible. One of the oldest metaphysical Christian groups are the Swedenborgians, founded on the teachings of Emanuel Swedenborg in 1787. The latter part of the 19th century also saw the founding of the Church of Christ, Scientist ("Christian Scientists") by Mary Baker Eddy, and Spiritism by Allan Kardec. Lastly, the mystical elements of Yorùbá, an African animistic tradition combined with Roman Catholicism via Afro-Cuban slaves, forming Lukumí (more well-known in America by its branch Santeria).

Two movements which are entirely unrelated in their founding share a common element of an additional Messiah or incarnation of Christ: the Unification Church and the Rastafari movement. These groups would also fall outside of traditional taxonomies of Christian groups.

There are also some Christians that reject the church altogether, believing that the only authority they should follow is God as embodied in Jesus. Christian anarchists feel that earthly authority such as government, or indeed the established church do not and should not have power over them. They also oppose the use of physical force in any circumstance and believe in nonviolence. Leo Tolstoy who wrote The Kingdom of God is Within You [1] was a Christian anarchist.

One peculiar body presents virtually the last Gnostic group in existence. The Mandaeans were discovered in obscurity on the coast of modern-day Iraq and Iran by Portuguese missionaries in the 14th century. They were erroneously identified as "Christians of John the Baptist", but reject Jesus Christ entirely as a false prophet, and following esoteric teachings they claim come from John the Baptist himself. Another small Gnostic group which purports itself to be a "Buddhist branch of original Christianity" are the Essenes. These syncretists are entirely unrelated to the ancient Jewish sect of the same name.

In addition, Christianity has partly inspired other religions, like early Islam and later Bahá'is, whose adherents do not consider themselves Christians but do consider Jesus to be a prophet (and in the case of Islam, the Messiah as well).

Considering this diversity, it may be impossible to define what Christianity is without either rejecting all definitions, or adopting a particular definition as authoritative and thus excluding others. In terms of the modern aim of scientific and objective definition, both options are considered problematic.

See also

- Religious denominations

- List of Christian denominations

- List of Christian denominations by number of members

External link

- Christian Denominations History, profiles and comparison charts of major Christian denominations.

- Denominational links from the Ecumenism in Canada site

- Canadian Church Headquarters