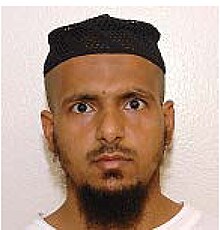

Said Salih Said Nashir

| Said Salih Said Nashir | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | September 29, 1969[1][2] Habilain, Yemen |

| Detained at | Guantanamo |

| Other name(s) |

|

| ISN | 841 |

| Charge(s) | No charge |

| Status | Held in extrajudicial detention |

Said Salih Said Nashir (a.k.a. Hani Saleh Rashid Abdullah; born September 29, 1969) is a citizen of Yemen, held in extrajudicial detention in the United States Guantanamo Bay detainment camps, in Cuba.[3] His Internment Serial Number is 841.

As of April 17, 2022, Said Salih Said Nashir has been held at Guantanamo for over 20 years.[4]

Combatant Status Review Tribunal[edit]

Initially the Bush administration asserted that they could withhold all the protections of the Geneva Conventions to captives from the war on terror. This policy was challenged before the Judicial branch. Critics argued that the USA could not evade its obligation to conduct a competent tribunals to determine whether captives are, or are not, entitled to the protections of prisoner of war status.

Subsequently, the Department of Defense instituted the Combatant Status Review Tribunals. The Tribunals, however, were not authorized to determine whether the captives were lawful combatants—rather they were merely empowered to make a recommendation as to whether the captive had previously been correctly determined to match the Bush administration's definition of an enemy combatant.

Allegations[edit]

The allegations against Nashir were:[4]

- a The detainee is associated with al Qaida and the Taliban:

- Originally from Lahaj, Yemen, the detainee traveled to Kandahar, Afghanistan via San’aa, Yemen; Dubai, United Arab Emirates; Karachi, Pakistan; and Quetta, Pakistan.

- The detainee was a recruited in Al Baraida, Yemen by an al Qaida facilitator.

- In late June 2001, while traveling from Yemen to Afghanistan, the detainee stayed in a Taliban guesthouse in Quetta, Pakistan.

- The detainee attended basic training at al Farouq training camp from July to September 2001, where he received instruction in the Kalishnikov rifle, Rocket-Propelled Grenades (RPG), hand grenades, land mines and explosives.

- The detainee attended two speeches by Usama Bin Laden while, training at the al Farouq camp.

- The detainee, armed with a Kalishnikov rifle, worked for al Qaida as a guard at the Kandahar airport.

- The al Qaida members guarding the Kandahar airport armed with Anti-Aircraft guns, SA-7, Rocket Propelled Grenades (RPG), and AK-47s.

- The detainee was given $1,000 US by an al Qaida operative for travel from Afghanistan to his home country of Yemen.

- The detainee was captured following a two and a half hour firefight in a Karachi Pakistan apartment, along with several other members of al Qaida during raids on al Qaida safe houses on 11 September 2002.

- Passports belonging to Usama Bin Ladin's family members were found at the suspected al Qaida residence on Taria Road in Karachi, Pakistan during raids on 11 September 2001.

- b The detainee engaged in hostilities against the United States or its coalition partners:

- According to an al Qaida associate, the detainee fought north of Kabul.

Transcript[edit]

Nashir chose to participate in his Combatant Status Review Tribunal.[5] On March 3, 2006, in response to a court order from Jed Rakoff the Department of Defense published a three-page summarized transcript from his Combatant Status Review Tribunal.[6]

First annual Administrative Review Board hearing[edit]

A Summary of Evidence memo was prepared for Said Salih Said Nashir's annual Administrative Review Board on November 23, 2005.[7] The three page memo listed twenty-two "primary factors favor[ing] continued detention" and three "primary factors favor[ing] release or transfer". The factors he faced included:

- His neighbor's account of his own experience traveling to engage in jihad is alleged to have inspired Said Salih Said Nashir to travel to Afghanistan. He is alleged to have accepted $300 from this neighbor.

- He was alleged to have stayed at a "Taliban guesthouse in Quetta, Pakistan and the Nebras guesthouse in Kandahar" on his way to the al Farouq training camp.

- He was alleged to have trained to use the Kalashnikov rifle, a pistol, rocket propelled grenades, hand grenades, land mines, Composition-3 (C-3) and Composition-4 (C-4) explosives, and how to read maps.

- He was alleged to have heard Usama bin Laden speak at al Farouq.

- He is alleged to have served as a guard at the Kandahar airport from September 11, 2001, to either late November 2001—or to December 3, 2001. His CO at Kandahar was the head of the suspect guest house in Kabul named Khan Ghulam Bashah.

- The factors state he spent nine weeks traveling through clandestine routes from Afghanistan to Karachi. They don't state an allegation as to what he did in the six months between his arrival in Karachi and his capture.

Second annual Administrative Review Board hearing[edit]

A Summary of Evidence memo was prepared for Said Salih Said Nashir's annual Administrative Review Board on October 20, 2006.[8]

The three page memo listed nineteen "primary factors favor[ing] continued detention" and three "primary factors favor[ing] release or transfer". The factors he faced were essentially the same as those he faced in 2005, except that the man who was alleged to have commanded his ten-man squad at the Kandahar airport was alleged to have been al Qaeda's commander of the Northern Front in Kabul in 2000.

Boumediene v. Bush[edit]

On June 12, 2008, the United States Supreme Court ruled, in Boumediene v. Bush, that the Military Commissions Act could not remove the right for Guantanamo captives to access the US Federal Court system. Further, all previous Guantanamo captives' habeas petitions were reinstated.

On July 18, 2008, his attorneys, Charles H. Carpenter and Stephen M. Truitt, filed a "Status report for Hani Saleh Rashid Abdullah" summarizing the renewed petitions on his behalf.[9]

Periodic Review[edit]

Nashir's Guantanamo Review Task Force had concurred with earlier review boards, and recommended he be classed as too dangerous to release, although there was no evidence to justify charging him with a crime.[10][11][12] Carol Rosenberg, of the Miami Herald, wrote that the recommendation from him Periodic Review Board concluded that while he was "probably intended by al-Qaida senior leaders to return to Yemen to support eventual attacks in Saudi Arabia," that he may have been unaware of these plans.

At the time of his capture, Nashir and five other men captured in Karachi at the same time were characterized as the "Karachi Six"—an al Qaeda sleeper cell.[10] However, by the time he had his Periodic Review Board, analysts had stepped back from this assessment, and concluded that the men's capture at more or less the same time was a coincidence, and did not indicate they had been working together.

Nashir was approved for transfer on October 29, 2020.[13]

References[edit]

- ^ https://int.nyt.com/data/documenttools/82922-isn-841-said-salih-said-nashir-jtf-gtmo-detainee/5ed02930c588211d/full.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ https://www.prs.mil/Portals/60/Documents/ISN841/20151215_U_ISN_841_GOVERNMENTS_UNCLASSIFIED_SUMMARY_PUBLIC.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "List of Individuals Detained by the Department of Defense at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba from January 2002 through May 15, 2006" (PDF). United States Department of Defense. Retrieved 2006-05-15.

- ^ a b "The Guantánamo Docket". The New York Times. 2021-05-18. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-01-20.

- ^ OARDEC. "Summarized Unsworn Detainee Statement" (PDF). United States Department of Defense. pp. 24–26. Retrieved 2008-10-28.

- ^ "US releases Guantanamo files". The Age. April 4, 2006. Retrieved 2008-03-15.

- ^ OARDEC (2005-11-23). "Unclassified Summary of Evidence for Administrative Review Board in the case of Nashir, Sa id Salih Sa id" (PDF). United States Department of Defense. pp. 7–9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-01. Retrieved 2008-12-07.

- ^ OARDEC (2006-10-20). "Unclassified Summary of Evidence for Administrative Review Board in the case of Sa id, Salih Said" (PDF). United States Department of Defense. pp. 51–53. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-01. Retrieved 2008-12-07.

- ^ "Status report for Hani Saleh Rashid Abdullah" (PDF). United States Department of Justice. 2008-07-18. Retrieved 2008-08-13.

- ^ a b

Carol Rosenberg (2016-09-30). "New Guantánamo intelligence upends old 'worst of the worst' assumptions". Guantanamo Bay Naval Base: Miami Herald. Archived from the original on 2016-10-01. Retrieved 2016-12-04.

Yemeni Said Nashir, whose lawyers call him Hani Saleh Rashid Abdullah, was held at Guantánamo as a member of the Karachi 6. A December 2015 assessment recast him as "probably intended by al-Qaida senior leaders to return to Yemen to support eventual attacks in Saudi Arabia." But, it noted, he "may not have been witting of these plans."

- ^

Carol Rosenberg (2013-06-17). "FOAI suit reveals Guantanamo's 'indefinite detainees'". Miami Herald. Archived from the original on 2014-11-21. Retrieved 2016-08-18.

The Miami Herald's Carol Rosenberg, with the assistance of the Media Freedom and Information Access Clinic at the Yale Law School, filed suit in federal court in Washington D.C., in March for the list under the Freedom of Information Act. The students, in collaboration with Washington attorney Jay Brown, represented Rosenberg in a lawsuit that specifically sought the names of the 46 surviving prisoners.

- ^ Carol Rosenberg (2013-06-17). "List of 'indefinite detainees'". Miami Herald. Archived from the original on 2016-04-11. Retrieved 2016-08-18.

- ^ https://www.prs.mil/Portals/60/Documents/ISN841/SubsequentHearing1/201029_UPR_ISN841_SH1_FINAL_DETERMINATION_PRB.pdf [bare URL PDF]

External links[edit]

- Who Are the Remaining Prisoners in Guantánamo? Part Seven: Captured in Pakistan (3 of 3) Andy Worthington, October 13, 2010

- The Guantánamo Files: Website Extras (11) – The Last of the Afghans (Part One) and Six "Ghost Prisoners Andy Worthington