Bilingual education could improve education outcomes in one of the world’s poorest nations.

In one of the world’s poorest countries, a model of bilingual education is emerging that could have a substantial effect on the nation. Landlocked, sub-Saharan Burkina Faso has battled high illiteracy and high dropout rates since gaining independence from France in 1960. Scholars say the problem stems from the lack of culturally appropriate education, and some have suggested bilingual education as part of a solution. To that extent, the Burkinabe government and local nongovernmental organizations have started a program, Bilingual Indigenous Community Education, which aims to instruct students in both their native tongue and the country’s French national language.

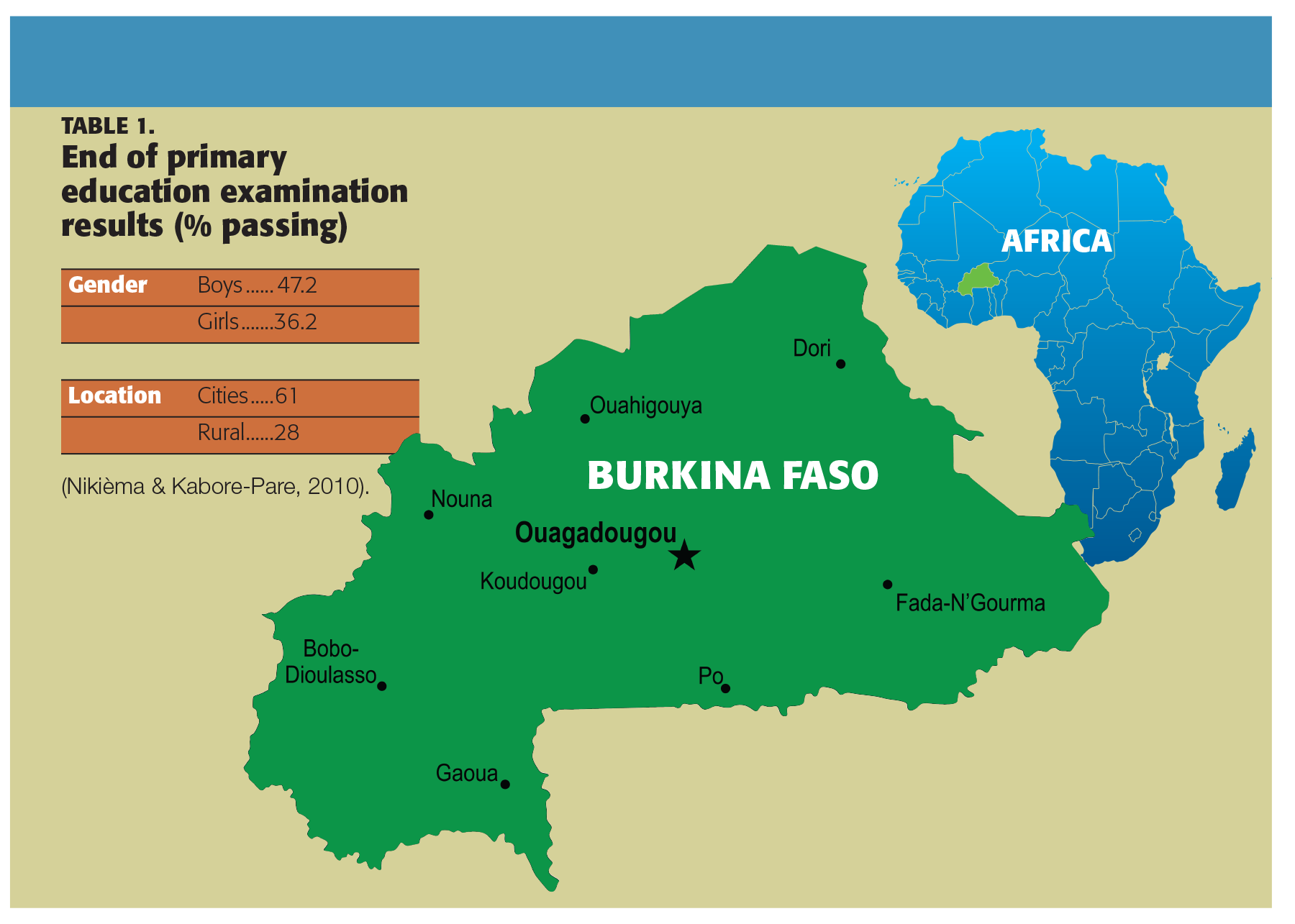

A brief history and overview of the region may help explain why. Burkina Faso borders Mali to the north, Niger to the northeast, and Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire to the south. Some 16 million people are spread over 105, 000 square miles of dry land. Yet the country relies heavily on agriculture, with 77% of the population living in rural areas (Institut National de la Statistique et de la Demographie, 2011). More than half the population is under 15 years old. Women bear an average of 6.2 children, and life expectancy is 51 years.

The Anglo-French Convention of 1898 ended the fighting between Britain and France and created new borders between their colonies. In 1919, the French further divided their area of land, separating Upper Volta from French Sudan and then further dismantled and divided this colony in 1932. By 1947, the French restored Upper Volta as a separate territory in French West Africa. In 1960, the nation gained its independence from France. It was renamed Burkina Faso in 1984, taking a word from each of the country’s two major native languages, Mòoré and Dioula. (Burkina is “men of integrity” in Mòoré; Faso in Dioula means “fatherland.”)

French tends to be seen as the language of development and hope, not only by the elite, but also by the Burkinabe people in general.

These geographical and historical summaries are significant because of their effect on the educational system. Burkina Faso has always lacked resources such as water, minerals, fertile soil, oil, and gas. Thus, during colonization, the French invested mainly in Dakar, Senegal, because it was not only more easily accessible but more profitable. As a result, Burkina Faso failed to develop critical infrastructures and fell behind in many areas, including education. The country has a literacy rate of only 46% (UNICEF, 2012), and a youth unemployment rate around 43% (Lavoie, 2008). The country has struggled to catch up with the rest of the continent; the first university in the capital city, Ouagadougou, was not established until 1974.

Traumatic colonial experience

The colonial experience was traumatic in many ways. The French imposed their language as the exclusive means of instruction, although there are 59 native languages in Burkina Faso, and 90% of the population speak just 14 of them. The Burkinabe progressively lost much of their individual and collective identities, preventing them from taking the initiative to change their educational systems.

While a report by the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs suggests that education scores are improving overall, the achievement rate of primary education has some critical gaps, as seen in Table 1.

This reveals a gender discrepancy, with boys scoring more than 10 points higher than girls. Girls often miss school because they are asked to stay home to help with chores, are promised in marriage at a young age, or are pregnant. Culturally, girls don’t tend to return to school regularly once they have a family. The second discrepancy is the significant difference between city and rural children. Rural children often don’t have as many resources as students in cities, they have less-qualified teachers, and often their parents are unable to help with their schoolwork.

Currently monolingual schools — in which the colonial language, French, is used as the language of instruction — remain the dominant model in the Burkinabe education system. This has seriously hindered Burkina Faso’s growth and development.

As the official language of Burkina Faso, French is used not only in monolingual schools but also in media, government offices, courts, and diplomacy. Street signs and the main newspapers are published in French. Given these realities, French tends to be seen as the language of development and hope, not only by the elite but also by the Burkinabe people in general.

But only 10% to 15% of the populace speak or understand French. Children of the country’s elite speak French and successfully attend monolingual schools; they’re the only ones with access to additional resources and tutoring. This means most children are expected to sit quietly at schools day after day, without being able to understand what is being taught. Some students become depressed and sick because they feel ashamed when they’re unable to participate in lessons. Additionally, corporal punishment is often used when students speak their native tongue, exacerbating their feeling of not fitting in the class. Since the exam administered at the end of primary school also is in French, children who come from families with limited means either fail or quit school (Lavoie, 2008).

Burkina Faso officially implemented bilingual education in 1994 with the opening of two schools. In 1996, a Burkinabe law made it acceptable to use national languages in formal schools, which are public schools that receive funding, staffing, and materials from the government. The government and l’Oeuvre Suisse d’entraide Ouvriere (OSEO, now known as SOLIDAR) have worked collaboratively to promote bilingual education throughout the country. SOLIDAR is a nongovernmental organization that works on behalf of less fortunate people in nations across the globe. So far, there are 204 bilingual public schools in 28 out of the 45 provinces, using eight national languages. Since 2008, the nation has opened an average of 20 bilingual schools per year, with 45 opened during the 2013 school year. In addition, there are 100 requests from diverse parent-teacher associations to convert monolingual schools into bilingual programs.

How it works

Bilingual education in formal primary settings follows the transitional model. Students spend their first year of school learning 90% in their native tongue and 10% in French. Second-year students learn in their native tongue 75% to 80% of the time and the remainder in French. In their third year, students are educated in both languages in equal amounts, preparing them for the fourth year when they transition to 20% of the time in the national language and 80% in French. This allows them to finish primary school at 90% of French instruction and the remainder in their local language. At the end of 5th grade, the students take their first national exam in French, le Certificat d’Etude Primaire (CEP).

The bilingual school curriculum is identical to that of the monolingual French schools except that it has added cultural and agricultural activities. These are intended to provide the students with skills they will need to be self-sufficient. Another significant difference is that bilingual schools not only encourage parent participation but consider it essential for success. Parents teach cultural modules that include songs and dances, as well as practical economical skills, such as basket weaving, how to seed a field, and how to raise cattle. In bilingual classes, children participate and even take leadership roles. This seems to boost class attendance, particularly among girls. In sum, bilingual education trains children to enjoy learning and helps them become independent and self-sufficient, which benefits their families, community, and the country as a whole.

Bilingual education faces many challenges, including a belief that children will be at a disadvantage if they aren’t proficient in French.

This new model of education must overcome several challenges if it is to continue to grow throughout the country and perhaps the continent. First, bilingual education must win the battle against the elite who oppose it for fear of losing ground. By preserving French as the main language of instruction, the elite believe their children will have an easier time getting administrative jobs. Another challenge to this model is the cost of developing materials in several native languages. Finally, most parents still believe that unless their children learn French fluently by having it as the sole language of instruction, they will be at a disadvantage. However, many linguists have proven that learning initially in a language that students understand enhances the learning of other languages later (Brock-Utne, 2007). This transitional model does not seek to erase French completely, but to introduce it as a second language later.

The Bilingual Indigenous Community Education program enables children to learn, helps keep them motivated, teaches them practical skills, and slowly integrates French into the curriculum once they are cognitively ready for it. In addition, this model allows more girls to attend school and enables parents to participate in their children’s education. Given its initial positive results, this model may well be the solution for Burkina Faso and other former colonies to grow in healthy ways and to reach their full economic, social, and cultural potential.

- Related: Global voices India: The true gift of education is more giving

- Related: Global voices Malaysia: A global effort for educational equity

- Related: Global voices Haiti: Making education a right

- Related: Global voices Brazil: A new agenda for Brazilian education

- Related: Global voices Russia: Russia’s own Common Core

- Related: Global voices Australia: Can schools compete?

- Related: Global voices Japan: Good teaching goes global

- Related: Global voices Israel: Helping underprivileged children succeed

- Related: Global voices | France: Leadership lessons for French educators

References

Institute National de la Statistique et de la Demographie. (2011). National annual statistics. Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso: Author. www.insd.bf/fr/IMG/pdf/Annuaire_finale2011.pdf

Brock-Utne, B. (2007). Learning through a familiar language versus learning through a foreign language–A look into some secondary school classrooms in Tanzania. International Journal of Educational Development, 27 (5), 487–498.

Lavoie, C. (2008). Education bilingue et developpement humain durable au Burkina Faso. Montreal, Quebec: McGill University. http://digitool.Library.McGill.CA:8881/R/?func=dbin-jump-full&object_id=40774

Nikièma, N. & Kabore-Pare, A. (2010). Les langues de scolarisation en Afrique francophone. Enjeux et repere pour l’action. Paris, France: Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Development.

UNICEF. (2012). Statistics: Burkina Faso. New York, NY: Author. www.unicef.org/infobycountry/burkinafaso_statistics.html.

Citation: Brion, C. (2014). Global voices Burkina Faso: Two languages are better than one. Phi Delta Kappan, 96 (3), 70-72.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Corinne Brion

CORINNE BRION is a doctoral student in educational leadership at the University of San Diego, San Diego, Calif.