The repressive messaging of family-life education reached its omega in the new college curriculum trend: the marriage course. This was not the old sociological or anthropological classes that studied marriage as a societal institution but classes that taught students how to be married, with the explicit goal of reducing divorce. They began taking hold in the late 1930s and received a boost during World War II when the army began making them available for soldiers awaiting active duty. By 1961, more than 1,200 US colleges and universities offered a marriage course.

Sometimes it was in the home economics department. Other times it was home economics–adjacent, in the sociology or social work department, sometimes required for home-ec majors, sometimes for everyone. Student demand evidently drove supply: the biggest problem, teachers reported, was keeping class size down. In a big departure, men were almost as likely to take the marriage course as women. When the Cornell home economics college discontinued its two marriage courses in 1957, it lost most of the men who took its courses, according to its annual report.

There was no explanation of why Cornell cut the classes, though home economics dean Helen Canoyer did say the department had upgraded the undergraduate child- and family-development difficulty level due to the preponderance of family-life education in high school. Maybe those marriage courses were easy As . . . though others reported that students were surprised to find they had to study for the class.

The standard textbooks were written by luminaries of the National Council on Family Relations. Robert O. Blood Jr.’s Marriage, Henry Bowman’s Marriage for Moderns, Evelyn Millis Duvall and Reuben Hill’s When You Marry, and Meyer Nimkoff’s Marriage and the Family promoted a model of marriage that was middle-class, companionable, democratic, deeply fulfilling emotionally and sexually, and lifelong. Which sounds nice. Except that they also said that a woman’s place was in the home. No wonder someone at the University of Michigan, presumably a student, scribbled on the frontispiece of Marriage, “This book is totally and completely SEXIST.”

By 1961, more than 1,200 US colleges and universities offered a marriage course.Like Catharine Beecher a century earlier, family-life specialists often disdained parents as needing better training. “Parents represent the last stand of the amateur,” Duvall wrote. It was particularly imperative to reach those immature married teenagers before they went too far astray. Despite a social-science veneer, the authors described anything outside the nuclear model as deviant or immoral. Only heterosexual, nuclear, intact families were acceptable. Duvall voiced the consensus when she wrote that divorced or single-parent families, which she called “broken,” could not teach healthy attitudes about parenthood. The danger was that these were social and medical scientists, experts, so their pronouncements held real weight.

Everyone, and especially every woman, should marry, they said. The only alternative was “a lifelong celibate career.” Women who couldn’t find a mate should move to Sacramento or Alaska, where men abounded, or lower their standards. Then, whom to marry? A person like oneself. These authors marshaled reams of data—data that conveniently supported gender and racial stereotypes—showing that “mixed” marriages usually failed. Even ridiculously minor differences hurt. Bowman warned against marriages where the woman was taller, because she would not respect her husband when he tried to wield authority.

A Protestant marrying a Catholic was akin to trying to leap a crevasse. Partners should be the same age: if the woman were younger, she would become a widow “when she is too young to stop living and too old to start over,” Bowman wrote. If she were older, her husband might find her ugly after menopause. Though even an age-mate might lose his head in middle age over a fresh young thing. Which would probably be at least partly his wife’s fault, because she had let herself go.

The only difference between partners the authors mostly did not address was the one most obvious to us, race, though Bowman warned that biracial children would be miserable because they would have “white aspirations” but be unable to fulfill them due to their “colored” appearance. (Mildred and Richard Loving, who later brought the lawsuit that ended miscegenation bans, wed in 1958.) None went so far as to say that men and women were too different to marry each other, of course. They followed Freud in stating that same-sex attraction was normal only as a passing, immature phase for teens. Some home economists still lived with women as either romantic partners or long-established roommates who became chosen family, including Flora Rose, now retired in Berkeley with her former student Claribel Nye. No one spoke of any such arrangement as anything other than platonic, because publicly known homosexuality meant career and sometimes actual suicide.

No detail was too picayune for the marriage-course authors to enforce convention as scientific gospel, even when they got the biology wrong. Working-class people had stronger sexual responses than middle-class, and girls led boys on because they did not experience strong arousal and did not realize how excited their date was getting, Duvall and Hill wrote. Eloping was dangerous, as was delaying the honeymoon. Most engaged women got their hymens medically stretched, Blood wrote, because in only 10 percent of cases was the membrane sufficiently elastic on its own for honeymoon sex to be comfortable—a tragedy when many couples would never have so much sex ever again, he claimed. The authors all advocated abstinence until marriage lest partners become permanently alienated from their friends, their families, and their personal values.

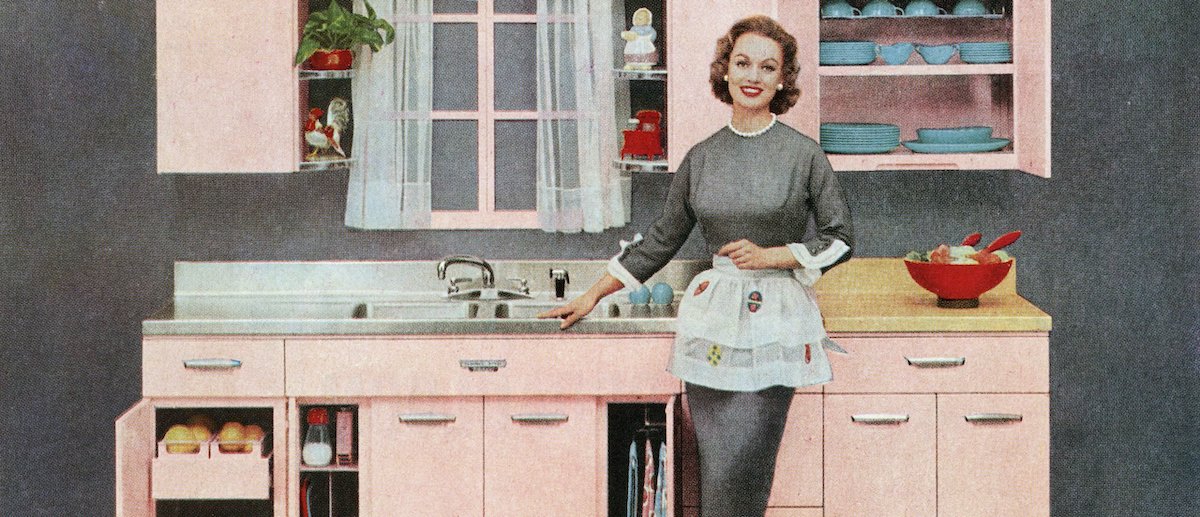

Cross your legs, stretch your hymen, and sacrifice any career ambitions you might have, and you could be happily married. That was the promise.Given those attitudes, it’s no surprise that these books warned against married women getting jobs. They worked overtime to tell women that there was fulfillment, control, and variety, not just drudgery, in homemaking. The need for a second salary was an illusion: Madison Avenue had snowed women into keeping up with the Joneses, they wrote. Society’s veneration of wage-earning occupations did not mean that they mattered more than housekeeping. No one could replace Mom at home. Though women might think they had time for a job, they really didn’t with all the many new, intellectually demanding tasks in housewifery these days. As for using a career as a tool for self-expression, most people, of both sexes, didn’t have much of a self to express, the authors scoffed. Besides, it’s not like the husband would pick up the slack at home, Blood wrote: working wives still did 75 percent of the housework compared to homemakers’ 85 percent. To ensure marital happiness, a woman should get a job only if her husband’s paycheck truly was inadequate. He suggested volunteering.

Judiciously, Bowman concluded that a young woman should still train to work as “a sort of insurance policy” if her fiancé or husband died or ran off. Of course, she must simultaneously prepare for homemaking. How about majoring in home economics? he concluded. Duvall and Hill unbent just enough to endorse jobs for city women whose children were older. It may have been relevant that Duvall was . . . a working city woman whose children were older. She was the only one of these authors to propose any societal solutions, including community kitchens, nursery school, and shorter workdays. She knew from her own experience that extra money from Mother’s work wasn’t frivolous. Before earning her doctorate in human development, she had written articles for Christian parenting magazines. “Five dollars meant meat on the table augmenting the macaroni and cheese,” she wrote years later. “The long-term rewards were becoming established as a published writer.”

So, cross your legs, stretch your hymen, and sacrifice any career ambitions you might have, and you could be happily married. That was the promise. Would it work? Who knew, Bowman said. He freely admitted that there was no research evidence that the marriage course improved students’ partnerships. But who cared, he wrote: there was no research evidence that most of the liberal arts curriculum was “effective” in whatever it aimed to do either.

_____________________________________

Excerpted from The Secret History of Home Economics: How Trailblazing Women Harnessed the Power of Home and Changed the Way We Live by Danielle Dreilinger. Copyright © 2021 by Danielle Dreilinger. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.