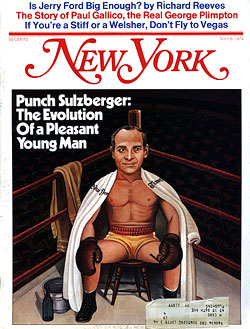

From the May 6, 1974 issue of New York Magazine.

Sons of distinguished fathers have to count themselves lucky if the world, out of spite or envy, does nothing worse than condescend to them. Arthur Ochs (Punch) Sulzberger may one day conclude that he was even luckier than that, for the worst that the world has been able to do to him since 1963, when he inherited the title and powers of publisher of The New York Times, is underrate him.

The newspaper he took over eleven years ago was secure in its reputation as the best in the business. It seemed so perfectly designed for making money that most observers thought that any amiable cipher could be installed at the top without harm. Although it continued to make fat profits through the sixties, The Times in fact was, by the standards of modern business practice, a mess—ignorant of any profound knowledge of budgeting, planning, or coherent growth strategy, and lacking, at the highest levels, young blood.

Worse, for the immediate harm it was doing, The Times had acquired a reputation, fully deserved, for being gutless and obtuse in its labor negotiations. Its lame posture at the bargaining table was almost a matter of principle. “Under my father,” Punch Sulzberger remembers, “it was the policy that The New York Times would never take a strike on an economic issue.” Slow to shed the burden of that heritage, Sulzberger in 1970 acquiesced in a humiliating agreement with Local 6 of the New York Typographical Union, led by the redoubtable Bertram Powers, in which The Times agreed to boost printers’ wages 43 per cent over the next three years and in return got nothing on the vitally important issue of automation in the composing room.

But last week, as he faced up to yet another negotiation with Bert Powers, Punch Sulzberger could rightly claim to have remade not only The Times but The New York Times Company, which owns the paper and of which he is chairman and president. By the standards of modern business practice, The Times Company is now up to snuff—with tightly disciplined budgets, sophisticated planning techniques, a demonstrably successful diversification strategy, and, at the highest levels, a team of young managers who had implemented these practices.

Better still, for the immediate good it could do, The Times Company had spent the past four years systematically psyching itself up to take a much harder line in dealing with Bert Powers. The 1970 negotiations with the Typographical Union had traumatized Sulzberger. “It was a reasonably humiliating experience,” he recently recalled. A Times executive with long experience in finding exact equivalents in forceful English for Sulzberger’s habitual understatements offered the following translation: “After Bert Powers had finished marching around in our composing room, we resolved that that son of a bitch was never going to do that to us again.”

In direct consequence, Punch Sulzberger began clearing out dead-wood executives and imposing budget discipline in earnest, and he intensified his search for other properties that would reduce the company’s dependence on The Times’s profits. Last week it was clear that The Times Company could risk taking a hard line with Bert Powers because it could afford to. In 1970, the year of its humiliation, The Times accounted for some 80 per cent of the company’s total earnings, which were not especially robust. In 1973, as a result of some highly profitable acquisitions, the newspaper accounted for just 60 per cent of total earnings, and the earnings themselves had soared close to an all-time record.

The pattern has continued in 1974. At his annual meeting last Tuesday, Punch Sulzberger reported the largest first-quarter profit in Times history. The company’s earnings base had broadened so much in four years that, with the pre-Easter advertising revenue already tucked away, Bert Powers could shut the paper down tomorrow and keep it shut for the rest of 1974, and The New York Times Company as a whole might do no worse than break even on the year.

It amounts to an extraordinary change in The Times Company’s fortunes and temper, but the transformation has gone all but unnoticed, especially on Wall Street. In 1969, with things soon to get much worse for the company, Times Company stock traded as high as 53. Last week, with things obviously better and the possibility of a strike not really relevant (“Don’t sell on a strike” is an old trader’s maxim), Times stock traded at 10½. “If all this had happened with a new guy in charge, it would be a major business story,” an investment manager who follows Times stock closely said recently. “But it’s the same guy, just Punch, so no one is noticing.”

Punch Sulzberger’s evolution as a businessman, once he was installed in his stately office suite on the fourteenth floor of the Times building on West 43rd Street, has been ignored in large part because of the peculiar nature of the newspaper business. Few readers care to think of it as a business. It’s more fun to second-guess the news columns and the editorial page than the profit and loss statement.

Thus, Sulzberger’s troubles as publisher in getting control of his own news department, especially the Byzantine struggle over the direction and accountability of the powerful Washington Bureau, are well known, not least because of Gay Talese’s full report of them in The Kingdom and the Power, which appeared in 1969. Less noticed, undoubtedly because much of it unfolded after Talese’s book came out, was Sulzberger’s adroit, deliberate attack on his business problems.

That these problems were ultimately Punch Sulzberger’s alone to solve was memorably perceived by Murray Kempton in his review of The Kingdom and the Power for Life magazine. Commenting on all the ambitious men discreetly maneuvering for preference on West 43rd Street, and savoring the ironic intent of Talese’s title, Kempton wrote:

… The best of reporters must come to a moment when he senses the truth as beyond him, the secret of some mocking god; and the most exemplary of his commanders arrives at an end when he knows that the real power is also beyond him, being the inviolable property of the pleasant young man who inherited it… .”

A pleasant young man … Kempton’s phrase was the perfect expression of the view that most people had formed, and still hold, of Punch Sulzberger. Just five years later, and with the benefit of hindsight, a veteran Times journalist remarked, “There are a lot of men walking around this town without their heads today because they thought all Punch Sulzberger was was a pleasant young man.”

The company he took over was not so much an organization as it was, in Sulzberger’s own phrase, “a set of fiefdoms.” His father, Arthur Hays Sulzberger, had continued to run it as a private business, accountable really to no one outside the family. “You would not believe the fourteenth floor ten years ago,” Punch remembers. “My father in his heyday had three secretaries, an office girl, and a sort of accounts man.” Running a far more complex enterprise, Punch Sulzberger gets by with one secretary.

“…’ A lot of men are walking around without their heads today because they thought Punch was only a pleasant young man’…”

The Times in those days also seemed to equate age with wisdom. That and the feudal relationships within the company gave it a management style reminiscent of the skyline of medieval Florence, towers of power having as little to do with one another as possible. “It was essentially a one-man show, a badly run show,” Punch Sulzberger says. “If you had a problem in circulation, say, you went and talked to Amory Bradford. If there was an advertising problem related to it, Amory went down to advertising and talked about it. Circulation and advertising never talked to each other.”

By Sulzberger’s own count, at least fourteen top corporate executives have left or been retired in recent years. The exodus had neither the texture nor the impact of a Putsch. Attrition, through death and mandatory retirement, played a part. But in time Sulzberger took to jumping junior men to positions of authority. “Telling lovely, decent, sweet human beings you’re promoting someone over them is terrible,” he says, “but if all they’re doing now is the job that was required fifteen years ago, that’s what I’m paid to do.”

As a result of that process, two relatively young executive vice-presidents now stand closest to Sulzberger in the hierarchy—Walter Mattson, 41, who came up through the production department and is now in charge of everything at The Times except the news department, and James Goodale, 40, trained in the law, who runs all the staff work that makes up the “headquarters group.” Another executive vice-president, Sydney Gruson, is a comparative fogy of 57. Gruson is now the only senior corporate executive who came up through the editorial side, having spent much of his career as a foreign correspondent. He heads up all other Times Company enterprises—now numbering some 42, including a radio station in New York (WQXR), a television station in Memphis, a gaggle of special interest magazines, like Family Circle, Golf Digest, and Tennis, a string of Florida papers, book publishing, and, most recently, music publishing.

The business floors of the Times building today resound with the jargon of modern management practice. The “M.B.O.” discipline—management by objective—has been in vogue for several years now. Even managers down in the middle ranks are solemnly charged with the preparation of five-year plans, systematically reviewed. Outside consultants—the Batelle Memorial Institute on a production problem, for example, or Price Waterhouse to guide information-gathering for sales incentives and share-of-market reports—are called in routinely. Sulzberger leads his top executives on periodic retreats to a conference center the American Management Association runs in Hamilton, New York, for deep thought.

The jargon can do no lasting harm, and the passion for planning can only help. In any case, everyone at The Times now understands that the fourteenth floor likes it that way. For it turns out that Punch Sulzberger has acquired a seasoned executive’s distaste for surprises and passion for neatness. “Maybe it was my Marine background,” he says. It’s possible, for little else in his life explains it.

Sulzberger did two tours of duty in the Marines, as an enlisted man in World War II and as an officer in the Korean War, separated by an undistinguished career at Columbia University (B.A., Class of ‘51) and equally unremarkable service in the Times newsroom as a cub reporter. Upon his discharge from the Marines, he did a stint on a Milwaukee paper, and gentlemanly service in The Times’s Paris Bureau, and then returned to New York as an aide to his father and his father’s direct successor, the late Orvil Dryfoos, Arthur Hays Sulzberger’s son-in-law. (“I was ‘assistant’ of everything,” he said, almost sadly, a few weeks ago.) The untimely death of Dryfoos in 1963, not long after the longest newspaper strike in New York City history was finally settled, led to the installation of Punch Sulzberger as publisher, at the age of 37.

Apart from radio station WQXR, The Times Company had done little to broaden its earnings base before Punch’s accession to power, and virtually nothing to broaden beyond the newspaper business. What little it had done was decidedly unrewarding. In 1949 his father had launched an international edition. It lost money consistently. In 1967, Punch merged it into the International Herald Tribune. In 1962, Orvil Dryfoos launched a West Coast edition. It, too, ran up heavy losses. In 1964, Punch killed it. He began to diversify not long after, in a modest and marginal way.

But it took eight years for Sulzberger to make a major move. In 1971 he struck a deal with Gardner (Mike) Cowles of Cowles Communications, Inc., for stock worth some $52 million. Sulzberger was severely criticized by some for the price he paid for what he got and for taking so damned long in the first place. Cowles Communications at the time had been hemorrhaging badly because of the failure of Look magazine, and Mike Cowles was known to be hard up for cash.

“… Last fall they even gave Bert Powers a guided tour of their strike-busting capabilities on the eleventh floor of the building …”

Sulzberger offers no defense on the latter count (“We were slow”) and no apologies about the price.

Timesmen claim that Family Circle magazine, which has grown impressively since they picked it up from Cowles (it now has the largest circulation in its field), currently yields a 33 1/3 per cent return on their original investment. “The Times Company netted $12 million on its non-Times properties last year,” a financial analyst observes. “Hell, the Memphis television station [also part of the Cowles package] came close to justifying the deal all by itself.”

As a result of the Cowles deal, there has been no loss of control over the company by the Sulzberger family. When the company went public in 1969, it had thoughtfully set up two classes of stock. The publicly traded “A” stock shares equally with the “B” stock in dividends and certain other rights, but control of the board of directors remains with the “B” stock, most of which is owned by a family trust. The trust will be dissolved upon the death of Punch’s mother, Iphigene Ochs Sulzberger (who is 81 and is planning a tour by airplane this spring of the chain of Florida papers). What happens thereafter is unknowable, of course, but literally everyone who knows them assumes that the Sulzbergers will continue to control the company and continue to hold The New York Times dead center in their minds. Despite the growing complexity of the company and the rising demands on his time, for example, Punch could not really imagine a set of circumstances that would make him relinquish the title of publisher of the paper. “That’s what it’s all about, really,” he said.

For readers, if not for businessmen, the test of the company’s strivings for efficiency will be what they do to the quality of the newspaper itself. Punch Sulzberger had chosen to enforce budget discipline on the news department first. (“I figured,” he said, “that if I could get them to live with it, how could the business side object?”)

This year, Managing Editor Abe Rosenthal has a budget of $22.5 million for the news department (not counting the Sunday department’s $4 million or the editorial page’s $1 million), and he says he can live with it. His staff has been cut by almost 100 people in the past four years, but he says there has been no loss of quality. “We reduced the staff by examining what we’re doing,” Rosenthal says. “There’s no longer an automatic replacement of clerks and reporters. And we may assign three reporters to a national conference instead of five.” Since budgets became a way of life around The Times, Rosenthal said, “I have found no area where there was an editor who would not cover a story or who wouldn’t authorize overtime because of the cost.”

It is possible that if there had been no obstacle in the way of automating his composing rooms all these years, Punch Sulzberger would not have chosen to diversify his company and set it firmly down the path toward becoming a communications conglomerate. “I’m really not a financial man,” he says. “I find it difficult to sit by the hour and listen to reports in great detail.” He did it, he says, to ensure the future of the newspaper his grandfather, Adolph Ochs, had bought in 1896 and which he and his successors had brought to greatness.

The fact is, though, that The New York Times Company has become a communications conglomerate (1973 revenues: $356 million; net profits: $17.6 million). Its biggest asset continues to be The Times, but the newspaper itself is now being run like a business. And having done all the obvious things, Punch Sulzberger at present has only one place to find a substantial source of new profit. That is in the direction of Bert Powers.

More than the profitability of The Times as such was at stake in the present negotiations. Few newspaper stocks are thought less of than The New York Times Company’s. Wall Street’s displeasure is visible in the market tables The Times publishes daily where, as anyone can see, investors will pay only $6 to command $1 of Times profit while they will pay eight for a profit dollar of the Times Mirror Company, the conglomerate that publishes The Los Angeles Times.

The gap is considerable—a 33 1/3 per cent difference—and several factors enter into such judgments. “All newspaper stocks took a hosing in the last few years,” says one investment manager who follows them closely, “but The Times Company has always sold near the bottom of the group because, one, Wall Street continues to think that the management is no good; two, they think New York City is dying; and three, because they think The Times is just not interested in making money.”

But if, by taking a hard line and winning with it in the present negotiations, Times management emerged in a new light, the price-earnings ratio could reasonably be expected to change for the better. If the Times management came to be regarded only as highly as the Times Mirror’s, it could add some $35 million to the value of its stock now outstanding—even if earnings stayed where they are.*

It is for such reasons that Wall Street’s good opinion was worth fighting for. And it was for the same reasons that, as crisis descended on New York’s newspapers last week, The Times, once a fat pussycat, was advertising itself as, and looking very much like, a tiger.

The no-more-Mr.-Nice-Guy mood at The Times was clearest on the eleventh floor of the Times building, where for weeks this spring, as a showdown drew nearer, The Times had assembled a staff of “exempt”—that is, nonunion and supervisory—personnel and had begun drilling them in procedures for getting out a newspaper without the help of Local 6. With a battery of I.B.M. Selectric typewriters, optical character readers, minicomputers, and photocomposition machines, an exotically assorted group ranging from vice-presidents to secretaries were making dry runs on some of the 150,000 words of copy ground out by the Times newsroom daily.

War games on that scale are obviously expensive, but Times management seemed determined to do everything it could think of to persuade Bert Powers that it meant business. Last fall they even gave Powers a guided tour of their strike-busting capabilities on the eleventh floor. And last week, in response to a question at the annual meeting, Punch Sulzberger cheerfully agreed the stock dividend could be higher, but he said he’d rather hold on to the cash right now.

The New York Times Company could count on a measure of understanding even among Times employees not ordinarily thought of as enemies of trade unionism. Associate Editor Tom Wicker, for one, son of a railroad worker and a former Newspaper Guild member, said he would unhesitatingly cross a Local 6 picket line if it should come to that. “If there’s a reactionary element here,” Wicker said, “it’s the union, not The Times.”

In the end, the present negotiations would finally come down to a test of power and will. “This is the biggest thing in the history of the newspaper,” said one close observer last week, “and it has to be the biggest thing in Punch Sulzberger’s whole life. It’s a major challenge to him as a newspaper publisher and a major challenge, even, to his manhood.”

If the stakes were high at the bargaining table, so too, because of the changes he had wrought, was Punch Sulzberger’s credibility.

*This dazzling prospect has also occurred to Bert Powers. “I’m aware that a reasonable settlement on automation could change the value of the Times stock,” he said recently, with a certain smile. “That, all by itself, could pay the cost of the settlement.”