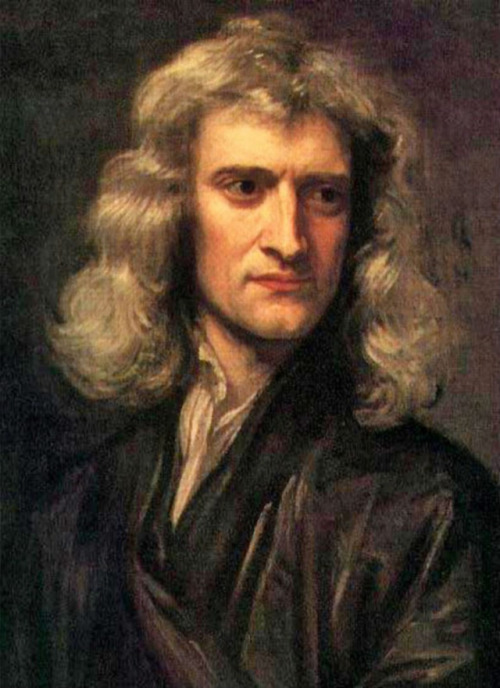

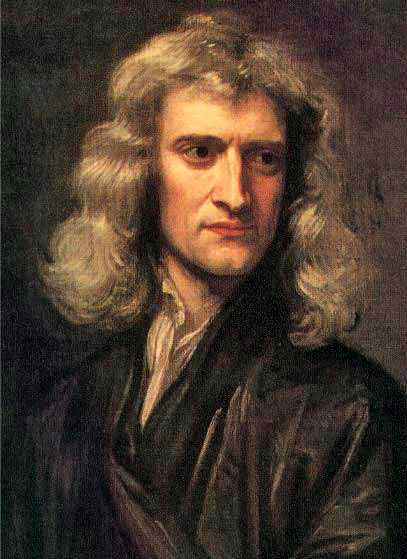

A Very Short Fact: On this day in 1643, English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, theologian, and philosopher Sir Isaac Newton was born.

“According to the calendar then in use in England, Newton was born on Christmas Day 1642 (4 January 1643 in most of Continental Europe). The first decade of his life witnessed the horror of the civil wars between parliamentary and royalist forces in the 1640s, culminating in the beheading of Charles I in January 1649. His uncle and stepfather were rectors of local parishes, and they seem to have existed without much harassment from the church authorities convened by Parliament to check for religious ‘abuses’. In his second decade he lived under the radical Protestant Commonwealth, which was replaced in 1660 when Charles II was restored to the throne. Newton was born into a relatively prosperous family and was brought up in a devout atmosphere. His father, also Isaac, was a yeoman farmer who in December 1639 inherited both land and a handsome manor in the Lincolnshire parish of Woolsthorpe. His mother, Hannah Ayscough, came from the lower gentry and (as was common for the period) seems to have been educated at only a rudimentary level. Nevertheless, her brother William had graduated from Trinity College Cambridge in the 1630s and would be influential in directing Newton to the same institution.

Newton’s father, apparently unable to sign his name, died in early October 1642, almost three months before the birth of his son. Newton told Conduitt that he had been a tiny and sick baby, thought to be unlikely to survive; two women sent to get help from a local gentlewoman stopped to sit down on the way there, as they were certain the baby would be dead on their return. Surviving against the odds, Newton was brought up by his mother until the age of 3, when she was approached with an offer of marriage by Barnabas Smith, an ageing vicar of a local parish. Smith was wealthy, and they married in January 1646 after he had promised to leave some land to her first born. Spending most of her time with her new spouse, she produced three more children before his death in 1653 (one of whom would be the mother of Catherine Conduitt). Although John Conduitt waxed lyrical about Hannah’s general virtues, and was careful to point out that she was ‘an indulgent parent’ to all the children, he emphasized that young Isaac was her favourite. Whatever the truth of this, Newton’s own evidence indicates that, as a teenager, he had an extremely difficult relationship with his mother, and historians have always found it difficult to make Conduitt’s account tally with the fact that for seven years Newton was effectively left in Woolsthorpe to be brought up by his maternal grandmother.” — From ‘Newton: A Very Short Introduction’ by Robert Iliffe

[Pg. 8-9 — From ‘Newton: A Very Short Introduction’ by Robert Iliffe.]

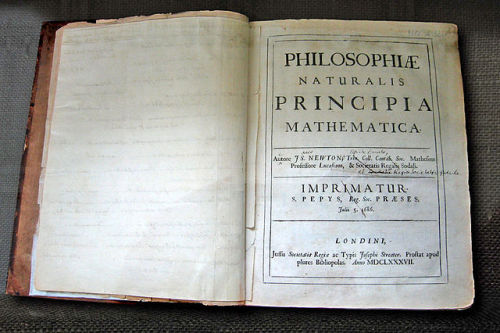

Image via Wikimedia Commons