To the surprise of no one, Bill Bowen *58 sprinted to the finish line.

Weeks before his death Oct. 20 at age 83, the 17th president of Princeton emailed dozens of friends to let them know the oncologist had told him and his wife, Mary Ellen, that further treatment would be futile. “The goal is as many good days as can be managed and to finish a few key tasks,” he wrote.

He’d spent a lifetime finishing tasks and finishing them well. His 20th book, Lesson Plan: An Agenda for Change in American Higher Education, came out last spring. His prominence in the public arena did not rest on being president of Princeton or the Andrew Mellon Foundation but on his ability to bring new, reasoned evidence to emotional debates about affirmative action, disinvestment, the excesses of big-time college athletics, and other matters. The half-price TKTS ticket booth in Times Square owes its genesis to a celebrated paper he and mentor William Baumol wrote in 1965 on the economic stringencies of the performing arts, bereft of productivity gains since it still takes four musicians to play a Schubert quartet.

Twenty years later, for an encore, Bowen and former Harvard President Derek Bok wrote The Shape of the River, a study vindicating the use of affirmative action by 28 selective colleges drawing on empirical data about the material success and civic contributions made by 54,000 graduates over a quarter century. Why speak ex cathedra when you could marshal facts instead? Bowen and Bok drew the evocative title from Mark Twain’s Life on the Mississippi on riverboat pilots’ need to know the contours perfectly to steer in darkness.

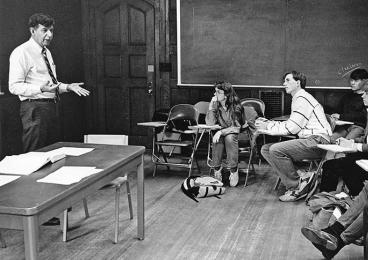

“Bill was ever the teacher, and he mentored large numbers of scholars, policy experts, and higher-education leaders,” President Eisgruber ’83 said in a statement. “I feel fortunate to have been in that group.”

His name, William Gordon Bowen, sounded to the manner born, but he wasn’t. Albert Bowen, a calculating-machine salesman in Cincinnati, died when his son was a senior at Wyoming High School. Bernice Bowen took a job as a dorm mother at the University of Cincinnati while he attended Denison University on scholarships, graduating Phi Beta Kappa and as a state collegiate tennis champion. He completed his Princeton economics Ph.D. in three years, joined the faculty, and by 31 was a full professor. President Robert Goheen ’40 *48 tapped the young labor economist as provost in 1967, despite their contrary views on whether all-male Princeton should admit women. Bowen expressed reservations that it would work, but Goheen suggested each could try to persuade the other. “Yes,” said Bowen, “and if it doesn’t work out the way I hope it will, I can always quit.”

“He was an operator with the sheer force of willpower and persuasiveness to make things happen.”

Tom Wright ’62, former vice president and general counsel

There was no quitting and no stopping coeducation. Bowen brought unparalleled energy inside Nassau Hall, acting as Goheen’s alter ego in that era of anti-war protests and fiscal constraints. The provost seemed “a whirling dervish” barreling into his reserved boss’s sanctum to Marcia Snowden, later the indispensable assistant to him and the next two presidents. He midwifed the birth of the Council of the Princeton University Community (CPUC) and its Priorities Committee, immediately a national model for shared governance, and dealt fairly but resolutely with protesters.

In 1973, a year after Bowen became president at age 38, he stood for free speech when Whig-Clio invited Nobel laureate physicist William Shockley to debate his crackpot theory on the genetic inferiority of blacks. In response to protesters’ demands that Princeton purge from its portfolio stocks of companies operating in South Africa, he articulated the rationale adopted by the trustees for “selective divestiture” that allowed investments in companies working for racial justice. He spent hours in tense forums fielding questions, prompting a colleague to quip that students “needed an opportunity every now and again to yell at the president.” He steered the course that led the CPUC to reject demands for a boycott of textile-maker J.P. Stevens over its labor practices, making the argument that if a university took sides in every contentious political debate, its ability to protect academic freedom from outside interference would be attenuated.

He achieved what Woodrow Wilson 1879 couldn’t with the creation of Oxford-style residential colleges. He lent moral support to Sally Frank ’80 in her lawsuit against the all-male eating clubs. Embarrassed by anti-Semitic policies in Princeton’s past, he championed the creation of the University’s robust Center for Jewish Life. Working with then-Dean of the Chapel Fred Borsch ’57, he moved Baccalaureate and Opening Exercises from morning worship times in the University Chapel to afternoons. “They became interfaith services,” says Borsch, later the Episcopal bishop of Los Angeles. “The idea was to make people feel entirely welcome.”

“He talked to people endlessly, essentially lining them up and bringing them along toward a goal he had set,” says historian Nancy Weiss Malkiel, one of Princeton’s first female professors. With Provost Neil Rudenstine ’56, the Renaissance scholar and future president of Harvard, “he catapulted Princeton into the front ranks of the research universities,” says Malkiel, later dean of the college for almost a quarter-century.

Bowen expanded the faculty, advanced the arts, and engineered the prescient move into life sciences. Molecular biologist and future President Shirley Tilghman was among the stars lured to set up shop in Lewis Thomas Laboratory.

“He was an operator with the sheer force of willpower and persuasiveness to make things happen,” says Tom Wright ’62, retired vice president and general counsel and one of Bowen’s first hires. Wright, then a young lawyer at the Ford Foundation, hadn’t even known Goheen was stepping down when a stranger showed up claiming to be the next president of Princeton. “I thought someone was playing a joke on me. He was young and had these big ears and a lot of hair. He didn’t look at all like the president of Princeton,” recalls Wright.

Bowen possessed “an instinctive understanding and an unerring judgment about how institutions work,” Rudenstine told The New York Times. He worked endless hours — in the office, at home, at the beach house in Avalon, in the air, “wherever he was,” says Snowden.

He carted a Dictaphone on business trips, dictating letter-perfect memos and letters. His annual reports, not a ledger of achievements but discourses on major challenges faced by all higher education, were widely circulated and read beyond Princeton.

Bowen was “incredibly good at understanding how other people were feeling,” says psychology professor Joan Girgus, whom he recruited to be dean of the college in 1976. “He was the engineer, the cheerleader, the enthusiast and the planner, the careful, let’s-do-the-process person.” He was also quick-thinking. After Bowen and Rudenstine interviewed Girgus, “Bill was going to drive me to Lowrie House to meet with the search committee. We get in the car, he stops and puts his hand on my head, pushes me under the dashboard and says, ‘Daily Princetonian reporter passing behind the car; just stay down there.’” The secret stayed safe.

A memorial service for President Bowen *58 will be held Dec. 11 at 1:30 p.m. in the University Chapel.

It ruffled some conservatives’ feathers that the liberal Girgus, a product of Sarah Lawrence and the New School for Social Research, was brought in from outside for the job. Ignore them, he told her. On her first day Bowen took her up to Freddie Fox ’39’s third-floor lair in Nassau Hall, a monk’s cell crammed with memorabilia. She was moved “that Bill took the time to show me that side of Princeton as soon as I got there.” The next day Fox showed up with a Class of 1905 hatband for Girgus; her grandfather was one of two Jewish students in the class.

It shocked everyone when Bowen and Rudenstine both decamped to Mellon in 1988. Girgus recalls sociologist Marvin Bressler’s wisecrack: “Oh, my goodness. Princeton is a mom-and-pop store, and Mom and Pop are leaving.” But Princeton was soon in the capable hands of fellow economist Harold Shapiro *64, who as president of the University of Michigan had often crossed paths with Bowen at gatherings of university leaders.

At Mellon, Bowen had the resources and the talent at his disposal to do the research that went into The Shape of the River and Crossing the Finish Line, a 2009 study based on the records of 60,000 students at top public universities that documented the price paid by low-income and minority students who did not attend the best institutions for which they qualified. He got the inspiration for JSTOR, a cloud-based archive on which thousands of libraries rely, at a Denison trustees’ meeting, wrestling with how to expand the library to accommodate its bulging journals. He also founded ITHAKA, the digital publisher.

After a last dinner out with the Bowens in mid-October, Shapiro dropped them back at home, then lingered while the couple — who met in fourth grade — walked inside. It was past 10 p.m. Shapiro looked up and watched as Bowen marched directly into his study. “He worked straight to the end. It was just his character.”